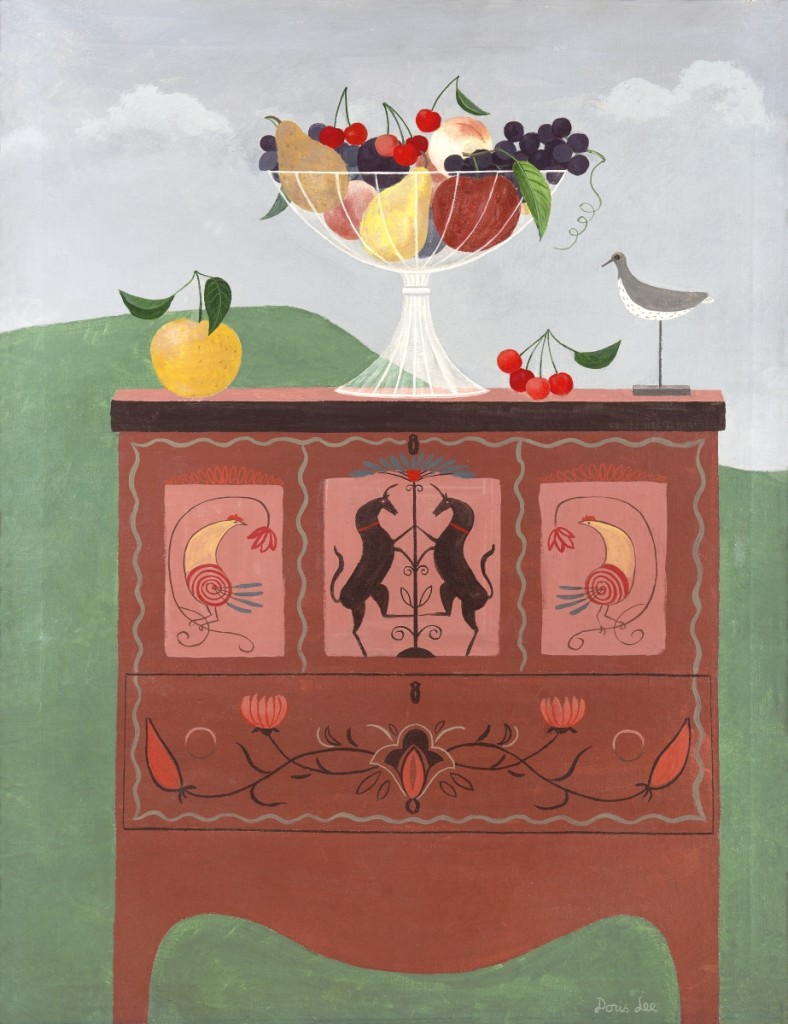

“Off to Auction” by Doris Lee, 1942. Oil on canvas, 24½ by 35½ inches. Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art. ©Estate of Doris Lee, Courtesy D. Wigmore Fine Art, Inc. Photo Dwight Primiano.

By Jessica Skwire Routhier

GREENBURG, PENN. – Doris Lee was one of the most popular artists of midcentury America. Honored with numerous awards, prestigious fellowships, solo museum and gallery exhibitions and lucrative commissions, she enjoyed a career that was a success by any measure. And yet her name is little remembered today, a casualty of an American art history in which (until recently) only certain kinds of painting and painters have been granted canonical status. “Simple Pleasures: The Art of Doris Lee” seeks to reintroduce this once-household-name artist to today’s museumgoers. The exhibition opens at the Westmoreland Museum of Art on September 26 and then travels to three other locations in the Midwest through 2023.

Co-curators Barbara Jones, of the Westmoreland, and Melissa Wolfe, of the St Louis Art Museum, argue that many interconnected factors contributed to the forgetting of Doris Lee. She was committed to figural painting and representational art at a time when abstraction was in the ascendancy; she pursued commercial projects without fear of being judged negatively for it; and she fully embraced humor in a time when many thought serious art should take on serious themes. In these ways she diverged from many (though certainly not all) of her artist contemporaries, but more significantly from the critics and curators of the next generation, who increasingly saw abstraction as the apex of American art and the archetypal artist as a troubled, rebellious iconoclast – and usually a man.

Doris Lee was not hostile to abstraction or to its practitioners; she lived and worked in the same New York art world as they did, befriended many of them, and shared mutual influences. In fact, she herself created nonobjective art at both the beginning and the end of her career. But even in those rare abstractions, her work was different. There is a lightness and a brightness to her paintings, a sense of simplicity and joy. It is ironic that this quality of her work, which was enormously popular and critically acclaimed when it was created, has come to be seen as out of touch with her times. The truth is more complicated, argue Jones and Wolfe. A central theme of this exhibition and book is to deconstruct the binaries that relegated Lee to a footnote in American art. Lee’s work, they demonstrate, is both simple and sophisticated, both joyful and serious, and visitors and scholars can approach it from those perspectives, and others, simultaneously.

“She has a consistent artistic vision throughout her whole career,” says Wolfe, by way of explaining that her multifigure canvases, her abstractions and her commercial projects are all of a piece, aesthetically speaking. Lee herself made a similar observation to a friend in 1943: “I don’t think the content of an artist’s work changes much even though the means (or style) changes drastically.” This was a remarkably prescient observation when so much of her career was still ahead of her. The wisdom had been hard-won some years earlier during her first major public success, when her painting “Thanksgiving” won the purchase prize at the Art Institute of Chicago’s annual exhibition in 1935. The award’s funder spoke out against the choice, declaring Lee’s painting unbeautiful, and founded a movement she called “Sanity in Art” in response. By all accounts, Lee laughed this off: a group of friends in Woodstock, N.Y., where she was based at the time, made her a mock award that merrily skewered her critics. “Her fame comes from negativity,” Jones says, recalling this incident, “but then to take advantage of that and to say, ‘I paint what I paint, this is my style’…she didn’t shrink from that; she didn’t really shrink from any of it.” Despite or perhaps because of the controversy, success followed: more museum acquisitions, more awards, more commissions, more shows.

“Fruits of Pennsylvania” by Doris Lee, 1946-47. Oil on canvas, 35¼ by 28 inches. The Penn Art Collection, University of Pennsylvania. ©Estate of Doris Lee, Courtesy D. Wigmore Fine Art, Inc. Photo Candace diCarlo.

It was no foregone conclusion that Lee would become an artist in the first place. Wolfe’s essay in the catalog, “Simple Joys and Serious Painting,” describes a middle-class upbringing in rural Illinois that did not offer any obvious opportunities apart from the occasional summer class at the Art Institute. Her interest in art was encouraged only up to a point; her parents insisted on a traditional college education rather than art school, and despite some rebellion (she was expelled more than once for, among other things, bobbing her hair), she followed a fairly traditional track into marriage upon graduation. Where this might have ended many a young woman’s artistic career, for Lee it was a new beginning.

A Paris honeymoon was extended for two months so that Doris could study at the Académie des Beaux-Arts. Ultimately her husband, Russell Lee, caught the art bug as well, making the decision to quit his engineering job and become a painter. Influenced by the avant-garde art education she received, Doris Lee initially produced mostly abstract work – until the Cubist painter André Lhote, with whom she studied in California, encouraged her to “paint subjects” instead, a suggestion she found liberating.

The Lees moved around for work and study – San Francisco, Paris again, New York – before settling in Woodstock to be near artist friends Arnold and Lucile Blanch. Woodstock’s lush surrounding landscape, quaint farmhouses filled with folk art and lively artistic community filled with colorful, creative and highly social people gave Lee much in the way of “subjects” to paint: fellow artists and neighbors appear in the vibrant “Beach Party;” paintings like “The View, Woodstock,” and “Dance Rehearsal” celebrate the town’s beauties along with its sense of community. “Moving to Woodstock for her was a pivotal decision,” says Wolfe. “The group of artists there, the diversity of styles, the sort of bohemian-ness of it and yet the professionalism – I think she just flourished in that.”

While at Woodstock, Lee also painted semi-imagined, semi-remembered scenes of her Midwestern upbringing. “Thanksgiving” is one of these, as are “Off to Auction” and “Harvest Time,” but there are also darker memories. In “The Widow,” which Wolfe thinks may be inspired by Lee’s two widowed grandmothers, a woman heroically subdues two panicking horses against the backdrop of a coming storm; in “Runaway,” a wild-haired girl speeds across a prairie on an unsaddled horse, raising the question, Wolfe notes, of which is the runaway. Such paintings complicate any perception of Lee’s work as benignly cheerful or anodyne. Lee herself noted that she felt “a sort of violence” as an artist; her work alternately reflects that violence, offers a proposed balm for it, and retains it just under the surface.

Wolfe sees in Lee’s highly detailed scenes a sense of play and absorption that she connects with other artists of the time. Lee relished things in a way that Action Painters did not, but the sheer density of the objects in her canvases offers something analogous to their work. “If you think of these huge Abstract Expressionist canvases where you can’t see out of the corners, the periphery, and you’re sort of absorbed into it,” Wolfe observes, “I think she also asks us to lose ourselves, it’s just in the absorption of the small things.” Paintings like “Beach Party” and “Thanksgiving” defy academic compositional conventions; the eye dances around and the viewer becomes lost in contemplation of the myriad details. Wolfe marvels over Lee’s enraptured response, in a piece for Life, to a collection of detritus at a Mexican flea market – “nails, keys, old purses, parts of electrical equipment,” objects that would escape the notice of most. There is something very modern, or even postmodern, about that sense of indiscriminate visual wonder, that elevation of the everyday, that voracious intake of inspiration.

“Thanksgiving” by Doris Lee, 1935. Oil on canvas, 28-1/8 by 40-1/8 inches. The Art Institute of Chicago, Mr. and Mrs. Frank G. Logan Purchase Prize Fund, 1935.313. ©Estate of Doris Lee, Courtesy D. Wigmore Fine Art, Inc. Photo: Art Resource, NY.

Like many modernists of her generation, Lee was also inspired by (and a collector of) American folk art. Its influence is readily apparent in works like “Fruits of Pennsylvania” and “Grapefruit Still-Life,” both of which consciously evoke Nineteenth Century theorem paintings. But Lee was also attracted to the popular expressions of her own time. An interest in music, particularly popular music, is evident in works like “The Violinist” and in commissions she took to illustrate The Rodgers and Hart Songbook and provide depictions of the musical Oklahoma! for Life. (Both Oklahoma! and the music of Rodgers and Hart, like Lee herself, have dark undercurrents that are largely forgotten in the sheer pleasure of their music.) Theatrical conventions undergird many of her Woodstock paintings, too, including “Dance Rehearsal,” of performers practicing outdoors for a local production; “The View, Woodstock,” which is framed by cords and curtains; and “New House,” where the homeowners sweep and prepare a bare, stage-like foundation as if building a set.

“New House” depicts another watershed moment for Lee, after she began a romantic relationship with Arnold Blanch and left Russell. Lee and Blanch never married but were partners for most of the second half of their lives; the new house they built was also in Woodstock, where they remained friendly with their ex-spouses. “At Home with Doris and Arnold” is a paeon to their unconventional partnership, with the specific fixtures of each artist’s workspace reflecting their individual processes and preferences. Lee and Blanch also began wintering in Key West, which offered a whole new arena of inspiration for Lee. She had traveled frequently for professional reasons, in part as a correspondent for Life, but in Florida she had the opportunity for sustained engagement with a place that was unlike anywhere else she had lived.

In Florida, Lee and Blanch became friendly with the painter Milton Avery and his wife, Sally Michel. Lee’s work from this time resonates with Avery’s – simple, increasingly abstract shapes and a modulated but still luminous palette – and Wolfe points out that the influence is mutual and extended to others in their circle as well. Jones echoes this, saying “you can almost see a cross influence and pollination between her and the Averys’ work.” Many of those Florida abstractions or near-abstractions also speak to or anticipate the work of other artists of her generation or slightly younger: her matter-of-fact portraits of food and kitchen utensils have much in common with the early work of Vija Celmins; Lee’s Vine paintings also bring to mind the paintings of Ellsworth Kelly as well as textile designs by Orla Kiely. “I don’t think she was ever derivative,” Wolfe says, “I think she was just really omnivorous.”

It seems possible that Lee might yet have reinvented herself successfully – continuing to adapt her style while remaining true to her “content” – if not for a 1968 diagnosis of Alzheimer’s that left her unable to work and dependent on care for the last decade of her life. It was one barrier that she could not work or laugh her way through, as she did so many others, and it surely contributed to the art world forgetting her just as her own memory started to fail. Despite this, Wolfe argues that her remarkable career and her refusal to let others marginalize it have continuing importance in the study of American art. “In an era when figuration, decoration and popularly appealing subjects were feminized and thus easily dismissed as incapable of serious meaning,” Wolfe writes in the catalog, “Lee resolutely embraced these elements and worked to release them from such negative connotations.” Lee and her work testify that the siloing of American art histories – parameters that most of us have come to accept to some extent – are actually constructions after the fact. “She just kind of moved along in the art world, not unaware, certainly, of what was going on, but really with her own vision,” Jones says. Doris Lee’s example shows us that humor can be as legitimate as seriousness, simplicity as valid as complexity, joy as rational a response to one’s time as despair – and that they can and do exist together at the same time.

The Westmoreland Museum of Art is at 221 North Main Street. For additional information, https://thewestmoreland.org or 724-837-1500.