Top honors of the Bonney collection went to this Pilgrim century two-drawer oak blanket chest with three panels and ebonized spindles that finished at $30,000.

Review by Rick Russack, Catalog Photos Courtesy John McInnis Auctioneers

AMESBURY, MASS. – On October 24, John McInnis Auctioneers sold the collection of the late Clifford Sanborn Bonney, which included several examples of first period furniture and accessories. There were Pilgrim century chests, Seventeenth Century stoneware, early silver and pewter, early fireplace accessories, prints, local history books, lighting, glass and more. Bonney, who worked in the silver department of Shreve, Crump and Low, restored and lived in the historic 1727 Seddon Tavern on the lower green in Newbury. It originally served travelers using a ferry to cross the Parker River and was once owned by Historic New England. Bonney also restored four other early homes in the area. He was an aggressive collector (and sometimes dealer) who bought much of his early material locally. Some of his Pilgrim century furniture had been bought from leading dealers of the day, including Israel Sack. He was president of the Newbury Historical Society for two years.

Although the last 16 years of his life were spent in Virginia, where he continued restoring old houses and collecting, he retained his strong feelings for the Newburyport area. As Bonney, who never married, wished, his entire collection was sold to benefit the Museum of Old Newbury.

According to Susan Edwards, executive director, the museum, which focuses on items with documented connections to the Newbury and Newburyport area, did not retain any of the collection. The proceeds from the sale will go to the museum’s endowment fund.

The second highest price of the day, $25,000, was earned by this 1670-1700 Massachusetts joined oak spice cabinet on ball feet, with a paneled door, several drawers and original butterfly hinges.

Jay Williamson, McInnis associate, described Bonney as “Fueled by his competitive nature, especially with other collectors in the Newburyport area, his attention to detail brought him the label ‘advanced collector.’ Whether we’re talking about the restoration of the Seddon tavern, or any of his other pursuits, his self-discipline brought him where he wanted to be.”

Two of the three top priced items, each Seventeenth Century examples of joined furniture, included Israel Sack in their provenance. Leading the day was a Pilgrim century two-drawer oak blanket chest, with three panels and ebonized spindles, that exceeded its estimate, finishing at $30,000. Second place honors would go to a circa 1670-1700 Massachusetts joined oak spice cabinet with a paneled door in a geometric design, several drawers and original butterfly hinges. On ball feet, it earned $25,000. Rounding out the top three was another two-drawer circa 1680-1700 blanket chest that took $12,980. It also had a three-panel front with ebonized turned spindles and retained its original pine top. It had been in the Katherine Prentis Murphy collection and was one of the pieces Bonney had purchased from Sack.

Murphy was one of the early collectors and publicists of Pilgrim century furniture and accessories, sharing her interests with Henry Francis du Pont, Electra Havemeyer Webb, Ima Hogg and others of that generation. In 1958, Murphy loaned a portion of her collection to the New Hampshire Historical Society for long term display and eventually some pieces were sold by Skinner. The McInnis catalog stated that this early chest was one of those pieces.

There was not much redware in the sale. At $12,000, this 15-by-17-inch slip-decorated redware tray, which Bonney bought from Gary Adkins, was the highest price ceramic item in the auction.

There were several other pieces of early furniture, all of which sold above estimate. A pair of Massachusetts Queen Anne chairs, circa 1730-80 with original surface, vase and block turning, and Spanish feet, earned $5,700. A William and Mary stretcher base chair table, circa 1730-60 reached $5,100. An early Eighteenth Century oak joined stool, estimated to bring $400, actually brought $3,600.

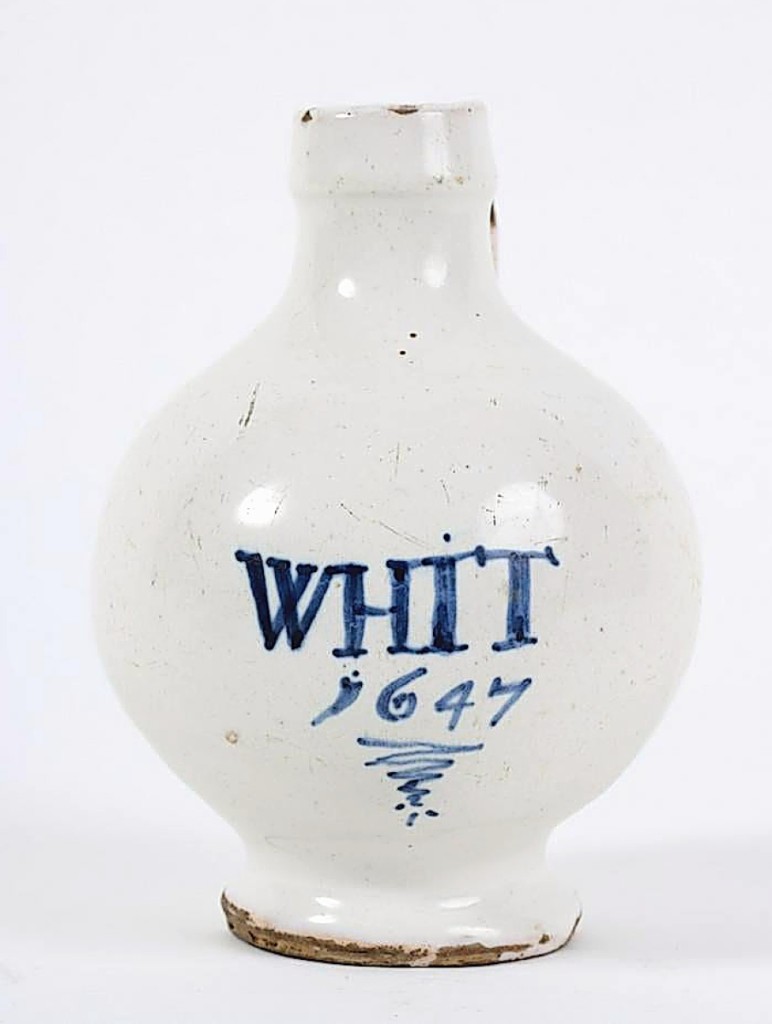

Bonney’s collection included several pieces of early stoneware and McInnis chose to start the day with three examples. The first three items sold were small salt-glazed stoneware bearded-man bellarmine jugs, a staple of German exports in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries and found in archeological contexts in all parts of the world. A molasses glazed jug, 7 inches tall, with a floral design below the bearded man, sold for $3,000. A white salt-glazed Westerwald pitcher dated 1698 realized $2,700. It was a particularly eye-catching piece, 10 inches tall, with raised leaf and scroll decoration and an embossed central panel. The armorial crest on the other side, partially deciphered as “Francis Al…,” indicated that the pitcher had been made for a Westerwald family, suggesting that, in addition to the thriving export trade, Westerwald potters were doing custom work for local families. Connie Helwig, researching the piece for dealer Hollis Brodrick, learned that an earlier flower pot with the same crest exists, suggesting that the potters worked for successive generations of the same family. One of the earliest dated pieces in the Bonney collection was a white-glazed stoneware jug, 6 inches tall with the date 1647 in blue, that realized $9,600.

Pewter was one of Bonney’s favorites and he sought early examples. A Seventeenth Century wrigglework beaker, 7 inches tall, reached $4,500. It was an exceptional piece, with portraits of William and Mary and decorative borders. A small mug, just 3½ inches tall, with wrigglework designs and the initials IM, sold for $270. There were dozens of Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century pewter plates, porringers, beakers and more, from England, Ireland and Germany, that sold for modest prices. A group of three American porringers finished at $440 and an Eighteenth Century charger, about 15 inches in diameter with London hallmarks, earned $150. A Westerwald stoneware stein with a pewter cover bearing the date 1764 realized $780.

One of the earlier pieces of ceramics in the sale was this white-glazed stoneware jug, 6 inches tall, with the date 1647 in blue. It realized $9,600.

Early lighting devices included numerous tin mounted onion globe lanterns. One, a 16-inch example with the tin pierced with stars and diamonds, brought $270. Others were sold in small groups as were groups of whale oil lamps that sold inexpensively. A six-arm wood and tin chandelier, in red paint, earned $420. There were two “wedding cake” tin lanterns. One, with a four-tiered tin top pierced with crescents and hearts, and red painted corner posts, realized $2,400, while another less elaborate example with four finials and embossed tin brought $960. Bonney also liked early brass candlesticks and a late Seventeenth Century Dutch example, with a mid drip pan, sold for $3,900.

Over and over during the Covid pandemic we’ve heard auctioneers say they are adapting to the restrictions in a variety of ways. McInnis utilized a unique approach. His gallery is on Main Street in downtown Amesbury. Although he could only have 12 bidders in the gallery, he set up chairs and a large monitor on the sidewalk in front of the gallery. It was a lovely fall day and as items came up that a collector outside wanted, they could come to the door and bid. McInnis said, “That worked really well. We had a good crowd of collectors and they stayed all day. We grossed about $300,000, and the executors, who were present for most of the sale, were satisfied. And it was a new experience for a lot of the people walking by. Most of our dealers were bidding online or by phone so this worked really well. We have to do what we have to do these days.” His online descriptions included as many as 17 photos per item.

All prices include the buyer’s premium as reported by the auction house.

For additional information, www.mcinnisauctions.com or 978-388-0400.