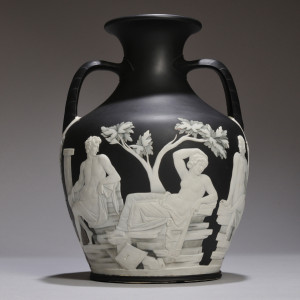

The star of the sale was a numbered first edition copy of Wedgwood’s Portland Vase. After several years of experimentation, in the last decade of the Eighteenth Century, Wedgwood made 43 copies of the vase, of which at least 11 were damaged during firing. Approximately 30 survive, most are in museums, and this piece with impeccable provenance, having been listed as being made for one of the original subscribers, sold for $147,000. Wedgwood considered it his masterpiece.

Topping the silver lots consigned by Colonial Williamsburg was a pair of George III sterling silver sauce tureens made by Benjamin Smith II and Benjamin Smith III in London, circa 1817–18. They were modeled after the Warwick vase, with lion-form finials, and brought $31,980.

Review and Onsite Photos by Rick Russack, Additional Photos Courtesy Skinner , Inc

MARLBOROUGH, MASS. — “We had a good day. All the marquee items sold and at strong prices,” said Stuart Slavid, senior vice president at Skinner, after the firm’s July 15 sale of European furniture and decorative arts. “The Lauer Wedgwood collection was strong throughout, and the material consigned by Colonial Williamsburg all did well. The provenance probably helped with those items. There were winners in the Chappel collection of early English ceramics and numerous other things did well.”

The top items included a Wedgwood vase that sold for $147,000, an almost unique Eighteenth Century flintlock candle clock that brought $52,890, a Russian enamel kovsh that realized $24,600 and an exceptional baby grand piano that also finished at $24,600. A surprise was a pair of marble figures that went out at $61,500 against a high estimate of $18,000. There may not have been a lot of bidders in the salesroom at the start of the sale — in fact, there were more Skinner associates manning the phones and internet platforms than there were bidders. But that had no effect on prices. The sale grossed $1,313,194.

As expected, from the Paul Lauer collection, the highlight of the sale was a black jasper, numbered example from the first edition of Josiah Wedgwood’s copies of the Portland Vase. Wedgwood considered these vases to be his finest creations and achieving the quality he sought took several years of experimentation. Beginning in the 1790s Wedgwood, according to his “oven book,” made 43 copies of the vase. Eleven were known to have been damaged during the manufacturing, and it is believed that only about 30 have survived. Most are in museum collections in the United States and abroad. The Portland Vase is modeled upon an ancient cameo glass vase, believed to have been made about 25 CE and excavated in Rome around 1590. Early owners included Cardinal Francesco Barberini (1597–1679) — thus, it has been known as the Barberini vase — and a pope.

One of the more unusual items in the sale, deaccessioned by Colonial Williamsburg, was a flintlock alarm candle clock, circa 1745, made in Schleswig. The complicated mechanism in an elaborate brass case allowed its owner to set the clock to activate the flintlock mechanism to light a candle, which would arise from the brass case. Perhaps no more than a dozen survive and this one fetched $52,890.

The vase eventually found its way into the collection of the dowager Duchess of Portland and then to her son, the third duke. In the mid-1780s he allowed Wedgwood to borrow the vase so it could be copied, and in 1810 deposited it in the British Museum for safekeeping. In 1845, the vase was smashed by a visitor to the museum and one of Wedgwood’s copies was used during the restoration. The one that Skinner sold was numbered “22” in pencil on the base, and its provenance can be traced back to Wedgwood’s original subscription list. Its price may be an auction record, according to Skinner.

Wedgwood produced other editions of the Portland Vase over the years, in different colors and sizes, but with differences in modeling. Examples in other colors, from other time periods were in Lauer’s collection and sold between $1,000 and $1,500. Other Staffordshire potters copied Wedgwood, and the sale included several examples.

Paul Lauer died this past April. According to Ron Frazier, president of the Wedgwood Society of Boston, “his passion was Wedgwood and he was known for frequently saying ‘big is beautiful. He really wanted the Portland Vase and flew over to London in 1971 to buy it. He apparently spent more money than he had on hand and had to call friends to send him enough money so that he could pay for it. He later said that he had been offered $250,000 for it but that he didn’t want to sell it. He was a very open and generous guy and frequently hosted meetings of our group at his home so that we could see some of his things.”

Some of the large pieces that Lauer liked did well at the auction. A 28-inch-tall black jasper dip “Apotheosis of Virgil” vase and cover, produced in the Nineteenth Century, realized $11,070 above an expected $7,000. From the same time period, a pair of 37½-inch black basalt vases on pedestals with acanthus leaves and bellflowers, reached $10,455, and a large black basalt vase and cover, with upturned loop handles and classical muses in relief, sold for $9,840, almost four times its estimate. In total, Lauer’s collection, which included some majolica and Mettlach, grossed $307,945. Together with Wedgwood’s First Day vase, sold in London for $625,000 a few days before the Lauer collection, it was a good week for Wedgwood, with sales totaling close to $1 million.

A pair of marble nude figures with putti, 58½ inches tall and signed “Prof. Chiurazzi,” sold for more than three times the estimate. The pair dated to the late Nineteenth or early Twentieth Century and achieved $61,500, one of the highest prices of the sale. The professor’s works were exhibited at the Pan-Pacific International Exposition in 1915.

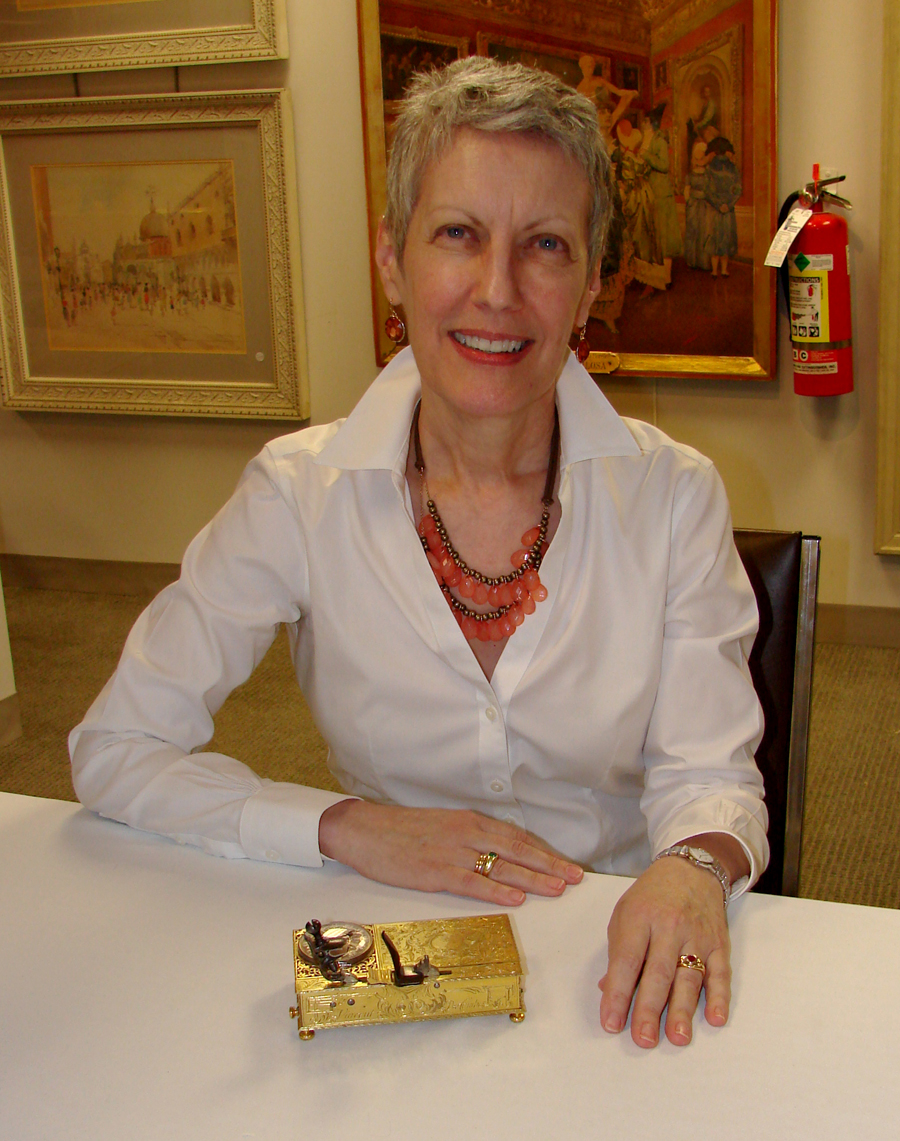

Several items in the sale were consigned by the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, deaccessioned with proceeds to benefit the acquisition fund. One of the more interesting items in the sale was part of this group. It was a flintlock alarm candle clock, a device made about 1745 in Schleswig. The complicated mechanism included a flintlock, similar to those used in firearms, a watch and a candleholder, all in an elaborate, engraved brass case. The fusee movement watch was signed “V Des Combes Schleswig” and it sold for $52,890. The owner could set the watch to activate the flintlock mechanism to ignite a small candle stored in the brass case. Janine Skerry, curator of metals at Colonial Williamsburg, was present and discussed the piece with Antiques and The Arts Weekly. She said that perhaps fewer than a dozen of these are known to exist. When asked why then would such an item be deaccessioned, she replied, “A decision to deaccession an item involves several criteria. In this case, there’s no record of these items ever having been owned in America, so it really doesn’t fit with our collections management policy.” The foundation’s accession policy focuses on examples of American and British fine, decorative and mechanical art, American folk art and archaeological artifacts and architectural fragments. “These materials help us understand life in Virginia, the American colonies and the greater North Atlantic from the Seventeenth Century through the early national period,” she explained.

Skerry added, “We are delighted with the results. Funds from this sale will allow us to celebrate the generosity of our supporters by making donor-credited acquisitions for Colonial Williamsburg.”

Williamsburg’s consignment included numerous pieces of Georgian silver, including items dating to the reigns of George II, III and IV, as well other pieces, and much of the materil exceeded the estimates. The sale included silver from other collections as well. Skinner’s catalog clearly noted the Williamsburg provenance when appropriate, and many of those pieces exceeded their high estimates.

Achieving the highest price among the 200 lots of silver was a pair of George III sterling silver sauce tureens. They were made in London by Benjamin Smith II and Benjamin Smith III, 1817–18. Each was modeled on the Warwick vase, with lion-form finials and engraved armorials. They were 13¾ inches tall, with 155.5 troy ounces of silver and finished at $31,980. A three-piece George III sterling silver tea caddy set made by Thomas Heming, London, 1762–63, went for $6,675. Each piece was decorated throughout with chinoiserie designs featuring a man picking tea leaves. Twentieth Century silver also performed well. Cataloged as Elizabeth II, a 34-inch pair of six-light sterling candelabras made by John Bull, Ltd, achieved $9,225.

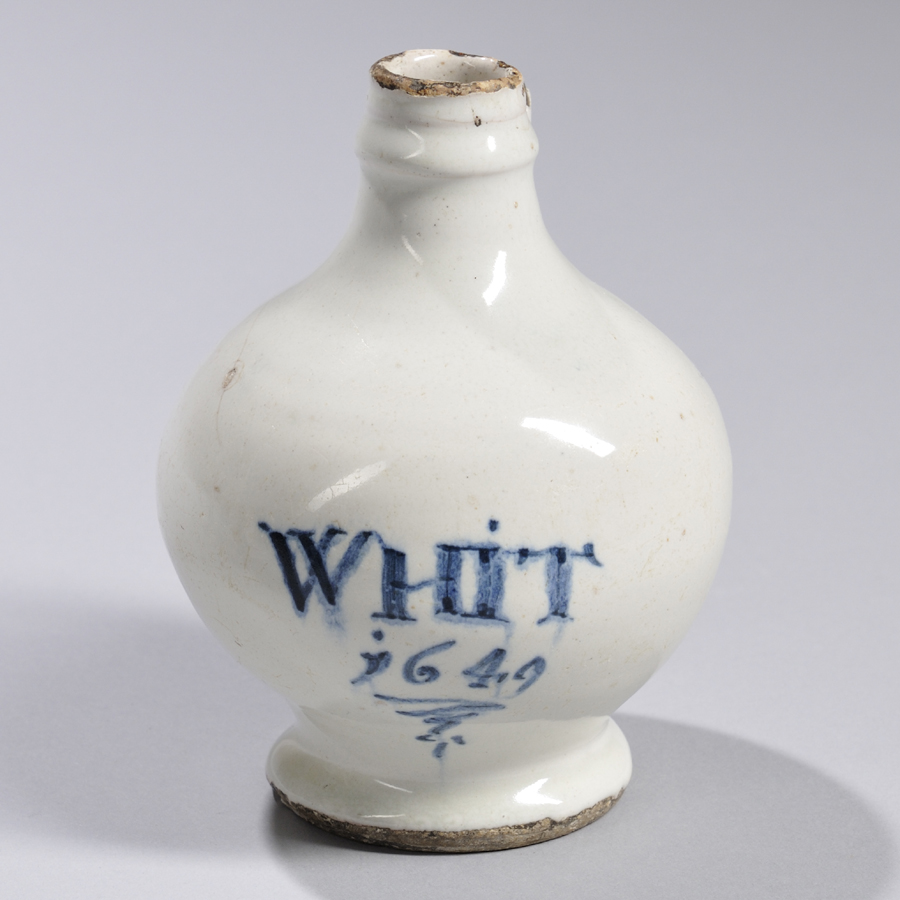

The sale included the final portion of the Troy Chappell collection of Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century British pottery, with a wide selection of tin-glazed earthenware, also known as delft, creamware, salt-glazed stoneware, examples with incised “scratch-blue” decoration and several dated examples. Leading the English delftware lots was a 103/8-inch punchbowl, circa 1756–63, probably made in London. The exterior was decorated with a polychrome chinoiserie landscape scene and the interior was inscribed “sucCes tO the bRiTh ArMs” (This is the way it was lettered and cataloged). It sold for $7,380.

The late Paul Lauer, part of whose collection of Wedgwood was sold, was photographed with the first edition copy of Wedgwood’s Portland vase over his left shoulder. Photo courtesy of Mary Frazier, an active member of the Wedgwood Society of Boston.

A Queen Anne delft charger, circa 1702–14, probably made in London, with a central design of the royal figure, reached $6,765. Rob Hunter, editor of Chipstone’s Ceramics in America, bidding by phone for a private client, bought a tin-glazed earthenware Wanli dish probably made in Southwark, attributed to the Pickleherring potworks, circa 1630. It depicted a central rocky garden with songbirds, and went for $3,075. Hunter said, “I was particularly excited to acquire the early bird on rock dish. I thought this was the most important object in this sale. Only a handful of examples survive from this seminal period of English delft production. All in all, I bought about ten pieces, including a brown salt-glazed stoneware double-wall mug, probably made in Nottingham, circa 1700–05 for a Southern museum.” It fetched $7,795.

Hunter has known Chappell for several years and included an article Chappell wrote on his collection in the first issue, 2001, of Ceramics in America. Speaking about Chappell, he said, “I have known Troy for more than 20 years and it was always enlightening to get together for occasional chats on English ceramic history. Without question, Troy’s knowledge, passion and commitment surpassed most every professional curator that I have met. An unusually high level of precise thought and purpose informed his approach to collecting, and I doubt we will ever see another collection like his. Fortunately, Troy has written an extended catalog of his adventure with English pottery and I expect it will be available in some form for other collectors and scholars in the near future. Troy always had a love for the accomplished painting found on really special examples of English delft. I know the Bristol Swan plate was one of his favorites and I bought it as a special keepsake for my personal collection.”

That plate, made in Bristol, circa 1740–65, depicted a swan, flanked by a tree and an architectural column, each with sponged foliage. It sold for $1,845. Chappell’s love for his collection was evident during the preview. He was answering questions about his items, often explaining in great detail what had drawn him to the piece.

The sale included much more than ceramics and silver. One lot that had been expected to do well — and did — was a Steinway Model B grand piano made of exotic woods and heavily inlaid. Steinway’s records indicated that it was completed in 1890 and delivered to Cottier & Co, a New York design firm. Daniel Cottier, a key figure in the Aesthetic Movement, was a stained glass artist, decorator, furniture maker and designer, working on churches in New York, Boston and Scotland and probably designed this piano for a specific customer. It sold for $24,600. A French gilt-bronze figural mantel clock, late Nineteenth Century, with a figure of a boy with a basket of fish, earned $1,107. There were several pieces of European furniture. A pair of Louis-Philippe-style giltwood benches on cirule legs reached $3,198, and an English Regency mahogany and gilt-bronze center table, first quarter Nineteenth Century, achieved $5,535.

All prices reported include the buyer’s premium. For information, 508-970-3100 or www.skinnerinc.com.