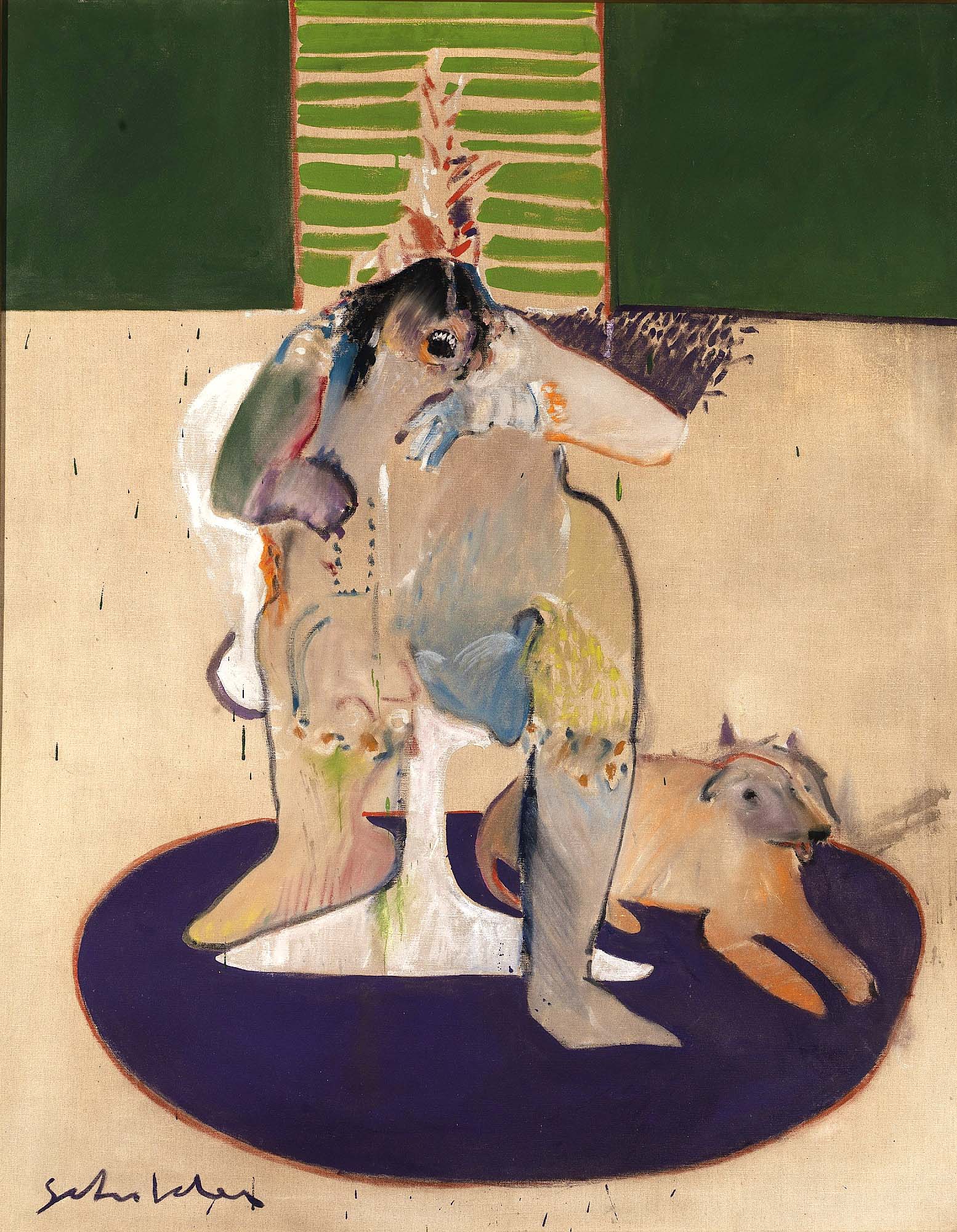

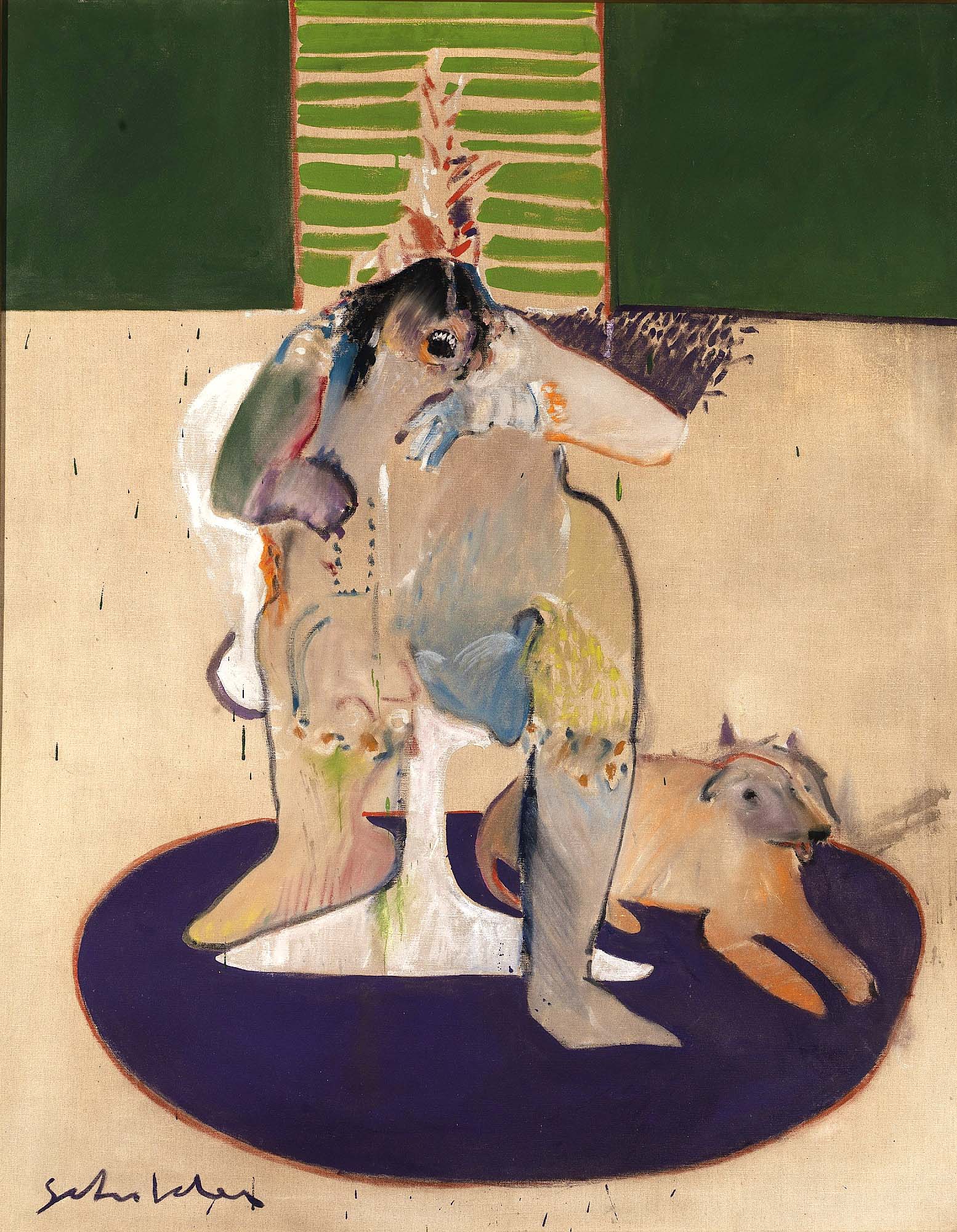

“Indian and Contemporary Chair” by Fritz Scholder, 1970, oil on linen. Smithsonian American Art Museum. Scholder rejected what he deemed “over-romanticized paintings of the ‘noble savage.’” This work, note the curators, “undercuts stereotypes that confine Native people to nostalgic landscapes, and points to the complexities of living in a modern world.”

By Laura Beach

WASHINGTON DC — The West of the Imagination, a six-part documentary series aired by PBS in 1986, was, for its time, remarkable for its insight and candor. From Catlin’s depictions of “a vanishing race” to Georgia O’Keeffe’s depopulated views of aestheticized New Mexico, the program and its accompanying book exposed Nineteenth through early Twentieth Century renderings of the American West as exercises in mythmaking, sometimes explicitly commissioned in the service of political or commercial agendas.

Today, amidst a national reckoning on who and what it means to be an American, the question of what defines the West seems considerably more complex than it did just four decades ago. On view at the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM), its final stop, through January 14, the ambitious traveling exhibition “Many Wests: Artists Shape an American Idea” asks as many questions as it provides answers.

“As a historian, I have always felt that a full, unvarnished, honest telling of history is the only way for us to move forward as a people, as a nation and as institutions,” Lonnie G. Bunch III opined in a Washington Post editorial in August. Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution, Bunch is in the forefront of an ongoing movement recently on full display in the nation’s capital, where visitors could survey temporary exhibitions of contemporary Native American art at the National Gallery of Art and the Renwick Gallery, then ponder the parameters of public art in the Monument Lab’s installation “Beyond Granite: Pulling Together” on the National Mall.

Left, “Los Cautivos, Talpa, NM” by Miguel A. Gandert, 1995, gelatin silver print, Smithsonian American Art Museum. Center and right, from the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, University of Oregon, Marie Watt’s 2015 mixed-media piece “Witness (Quamichan Potlatch 1913)” and “Buck,” a 2015 acrylic on canvas by Rick Bartow.

“Many Wests” moves beyond these related initiatives in its breadth of perspective. It features works in various media by 48 artists, most of whom are from marginalized communities – Asian-American, Black, Indigenous, LGBTQ+ and Latinx – and nearly all of whom are living or recently deceased. Implicitly, the show seeks to demolish the cultural Continental Divide that estranges region from region and museum from museum. Most of all, it means to banish, as the organizers put it, “images of rugged colonial settlers, gun-toting cowboys, or scenic expanses of vacant land,” stereotypes that distort and damage.

“Many Wests” is one in a series of exhibitions created through a multiyear, multi-institutional partnership formed by SAAM as part of the Art Bridges Cohort Program. Established by Alice Walton, the founder of Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Art Bridges promotes public access to American art and encourages collections sharing among institutions.

Coordinator for the Art Bridges Cohort Program at SAAM and project manager for “Many Wests,” Anne Hyland recalls the exhibition’s beginnings in 2018, when SAAM former acting chief curator E. Carmen Ramos, now at the National Gallery of Art, and SAAM senior curator Virginia Mecklenburg applied for the grant. Led by SAAM director Stephanie Stebich, who brought with her years of prior experience at the Tacoma Art Museum, the team selected four institutional partners, all located in rapidly diversifying areas of the West: the Boise Art Museum in Idaho; the Utah Museum of Fine Arts in Salt Lake City; the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art in Eugene, Ore.; and the Whatcom Museum in Bellingham, Wash.

This archival pigment print from the collection of the Boise Art Museum is one of a quartet of images by Wendy Red Star from her “Four Seasons” series of 2006. The Montana-born artist depicts herself in traditional Crow dress within four fabricated landscapes, mocking the diorama settings in natural history museums.

“We began planning the show in April 2020 and did everything over Zoom,” says Hyland, recalling the challenge of organizing an exhibition with far-flung colleagues during the depths of the pandemic lockdown. “We started each meeting by checking on one another. ‘How are you doing? Is your family healthy? Are your spaces open?’ It strengthened our bond.”

Hyland continues, “At SAAM, we quickly shifted from looking at our own holdings to assessing the strengths of each museum. It was a process of identifying the great, powerful works from each collection that we could craft into a single exhibition. It was fun focusing on how to serve the communities of these very disparate regions. SAAM is the show’s only East Coast venue. We are presenting artists that may not have a strong presence here but are well established on the West Coast.”

With six curators working on the show, writing was a particular challenge. Hyland notes, “Each curator was responsible for writing about the works from her museum. We met virtually once a week, sometimes more, for about a year and a half to go over the text and editing, the voice and language. All text went through SAAM’s publications department. It was a strange thing to grapple with, but we benefited from the constant, virtual connection.”

“The Fallen” by V. Maldonado, 2018, acrylic on canvas. Collection of the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, University of Oregon. Born in Michoacán, Mexico, in 1976, Maldonado “uses the imagery and cultural significance of lucha libre wrestlers, especially masks, to represent double-consciousness and how marginalized groups and individuals often feel both seen and invisible.”

SAAM also benefited from being the show’s final stop. “Being able to rely on my colleagues, to understand why they made certain choices in pairing works and to see the pieces in real spaces was such an advantage. I’m immensely grateful for their guidance and mentorship. The SAAM Art Bridges registrar, Edward Bray, traveled to each venue. His knowledge of the physicality of the pieces was important when we put pen to paper to design the installation here at SAAM,” Hyland reveals.

Installed on SAAM’s first floor and loosely organized into three sections, “Many Wests” categorizes artists as “Caretakers,” “Memory Makers” or “Boundary Breakers.” The labels correspond with the individual’s instinct for preserving cultural tradition versus upturning it, impulses that upon examination are not mutually exclusive.

Beckoning visitors into the show is the vivid “Summer,” from the “Four Seasons” series of artfully staged, color-saturated photographs by Wendy Red Star (Apsáalooke/Crow, b 1952), who satirizes the diorama, once a staple of natural-history museums. The print humorously invokes one of the show’s main themes, the artificiality of tired, patronizing stereotypes.

“Caretakers,” write the organizers, “demonstrate a commitment to the stewardship of land, history, language and culture.” Among the best known are Awa Tsireh (San Ildefonso Pueblo, 1898-circa 1955), whose stylized renderings in watercolor preserved aspects of Pueblo Indian ritual and belief even as they shrouded sacred knowledge from outside scrutiny, and Fritz Scholder (Luiseño, 1937-2005), who bridged cultures, asserting himself — and by extension, all Native Americans — into the mainstream of American life in his ironic 1970 painting “Indian and Contemporary Chair.”

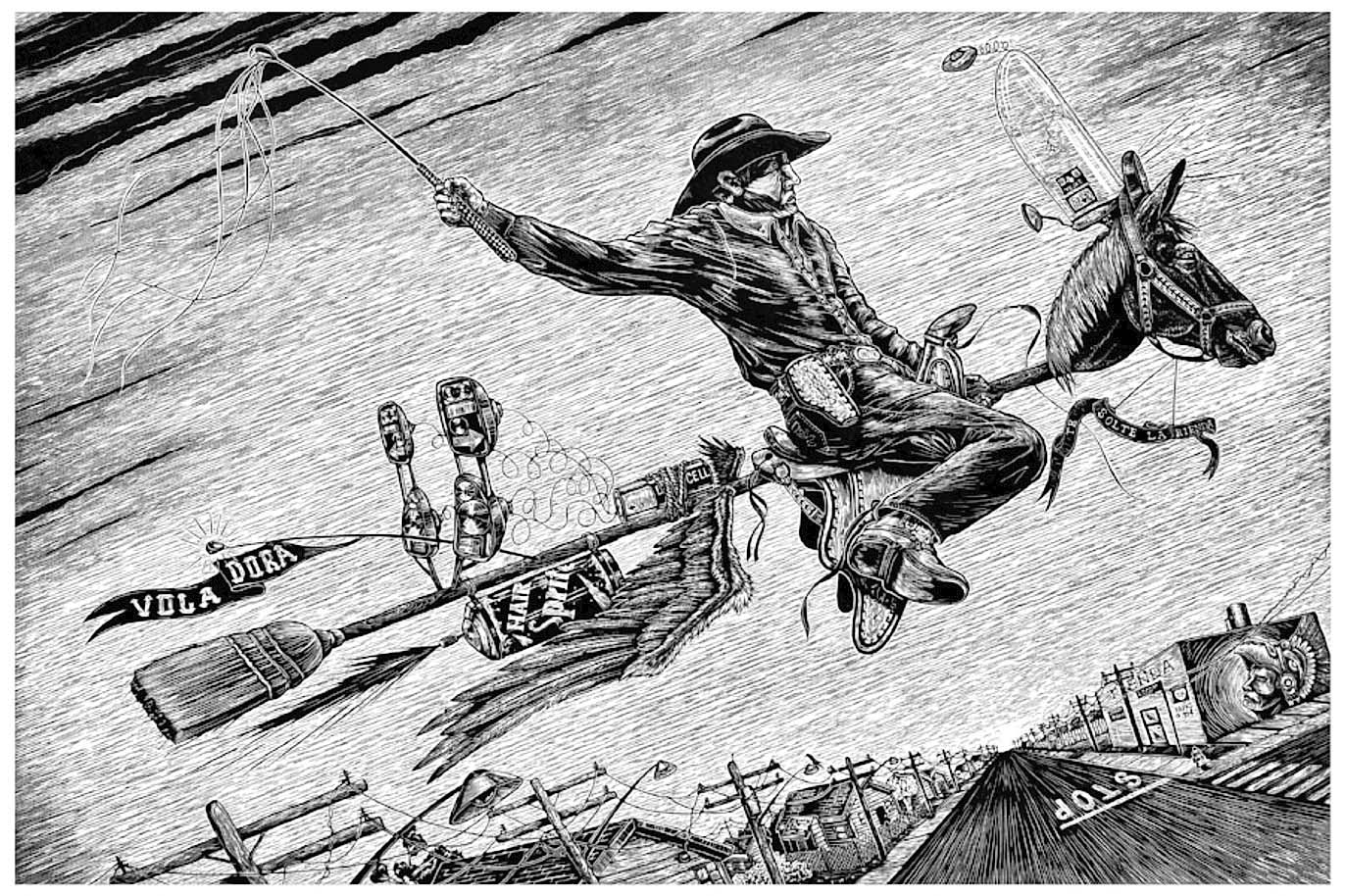

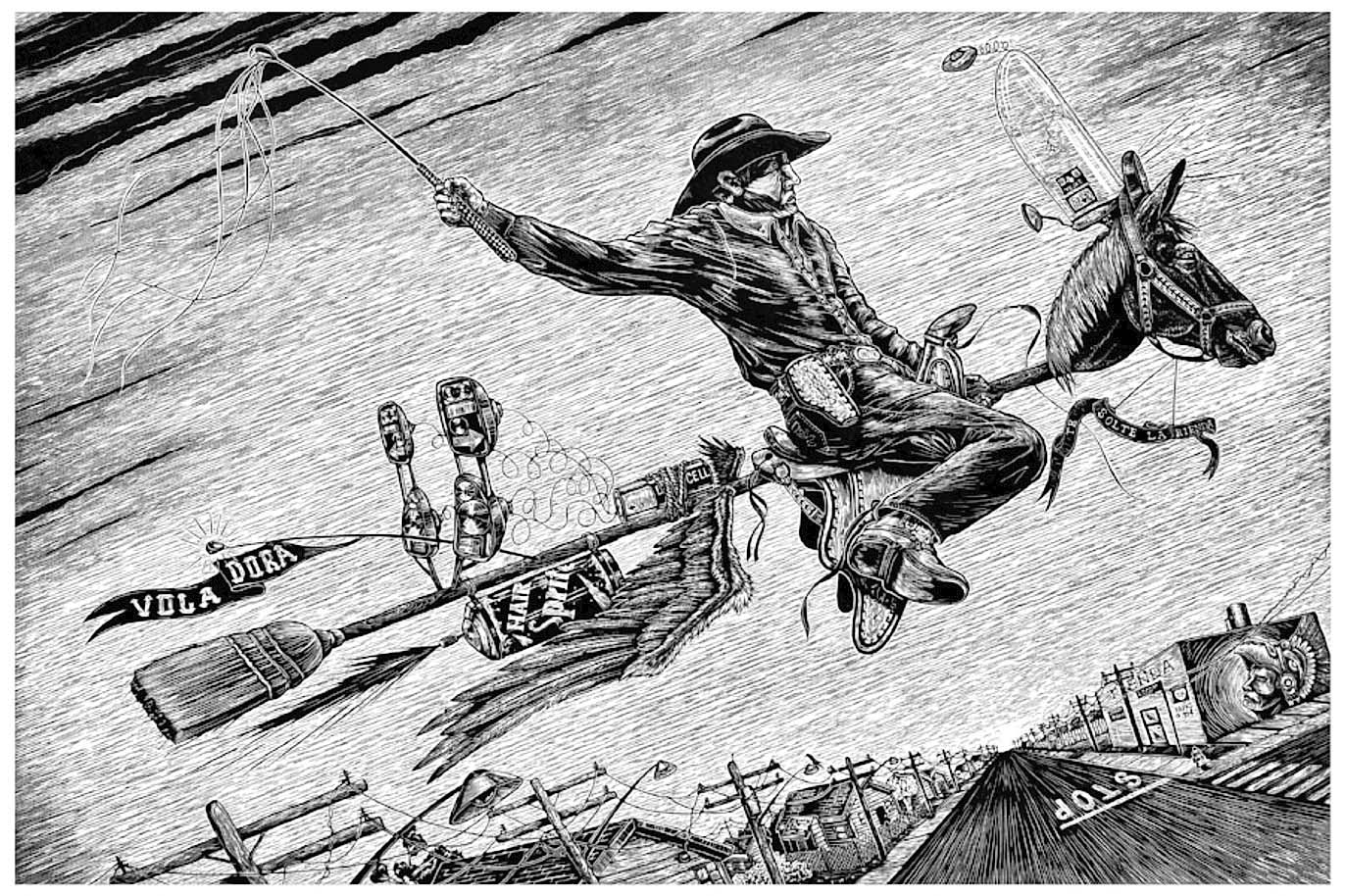

“Montando a la Escoba Voladora (Riding the Flying Broom)” by Juan de Dios Mora, 2010, linocut. Smithsonian American Art Museum. The artist’s exploration of immigrant life in Texas combines fantasy and realism. This work was inspired by Mora’s father, who was creative in his use of discarded materials.

In “Witness” of 2015, Marie Watt (Seneca, b 1967) embroidered a Hudson’s Bay blanket, the latter a decorating staple as well as a symbol of European subjugation of Native North America, with a scene of a 1913 potlatch, or feast day marked by gift-giving, reimagining the Coast Salish celebrants as protesters with upraised fists. The United States and Canada banned potlatches between 1885 and the 1950s.

An old favorite, Jacob Lawrence (1917-2000) joins relative newcomers Barbara Earl Thomas (b 1948), Juan de Dios Mora (b 1984) and Roger Shimomura (b 1939) in “Memory Makers,” devoted to artists who resurrect neglected histories of the West. Thomas’s inky linocuts illuminate the assimilation of African Americans into the maritime culture of the Pacific Northwest. Mora provides a similarly affectionate tribute to his father’s hardscrabble existence as an immigrant with a flair for making do despite his material poverty. Shimomura’s “American Infamy #2,” resembling a classical screen, is upon closer inspection a comment on the unjust internment of Japanese Americans during World War II.

The show’s “Boundary Breakers” challenge simplistic notions of personal identity and geographic borders, revealing the West to be a colorful tapestry of diversity. Of Mi’kmaq and Onondaga descent, Gail Tremblay (1945-2023), used traditional techniques to weave a “Peace” basket of unconventional materials: 16mm film, leader, rayon cord and thread.

“An Iroquois Dreams That the Tribes of the Middle East Will Take the Message of Deganawida to Heart and Make Peace” by Gail Tremblay, 2009. Whatcom Museum. Mocking American cinema’s stereotypical depictions of Native Americans, the artist used traditional techniques to make this basked of film, rayon cord and thread.

Similarly, Raphael Montañez Ortiz (b 1934) splices together 16mm film to create a surreal inversion of an American Western in his 1957-58 “Cowboy and ‘Indian’ Film.” The work from SAAM’s collection was one of the first selected for the show. Of it, Hyland says, “Some of the images are backwards or upside down, and the sound is disorienting. This piece quite literally destroys harmful stereotypes of the American West.”

Some “Boundary Breakers” critique their own communities. Raised a Mormon, artist Angela Ellsworth (b 1964) is an openly gay descendant of the Church of Jesus Christ of The Latter-Day Saints’ prophet Lorenzo Snow. Pierced with corsage pins, Ellsworth’s “Seer” bonnets, referencing the 35 wives of religious leader Joseph Smith, are both alluring and terrifying, a disturbing meditation on the struggles and resilience of Utah’s settler women.

The most arresting portrait may be Angel Rodríguez-Díaz’s (1955-2023) fiery likeness of the Chicana poet and novelist Sandra Cisneros, best known for The House on Mango Street. “Many Wests” generally seeks to make visible those whom history has overlooked. With pride, it in this instance references celebrity.

The show’s curators will reunite on the evening of Thursday, October 26, for an online conversation revisiting the collaborative process among partner institutions. Eleanor Jones Harvey, senior curator at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, is moderating the virtual panel featuring Hyland, Amy Chaloupka of Whatcom Museum, Melanie Fales of Boise Art Museum, Danielle Knapp of Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art and Alisa McCusker of Utah Museum of Fine Arts. Hyland will provide an art historical overview of the project and exhibition on Wednesday evening, November 29, in the museum’s McEvoy Auditorium.

“The Protagonist of an Endless Story” by Angel Rodríguez-Díaz, 1993, oil on canvas. Smithsonian American Art Museum. The “protagonist” of this painting is Chicana novelist and poet Sandra Cisneros, best known for her debut novel, The House on Mango Street.

“Many Wests” opened in Washington on July 28, at the height of the city’s tourist season. Hyland says, “It’s been wonderful seeing people from all over in our gallery spaces. The show encourages visitors to think more broadly about the stories we are telling through these works of art. We’ve been gratified by their response. It’s been such a pleasure working on this project. Thinking about how to tell stories through art is a beautiful thing.”

Smithsonian American Art Museum is at Eighth and F Streets NW. For more information, 202-633-7970 or go to www.americanart.si.edu.