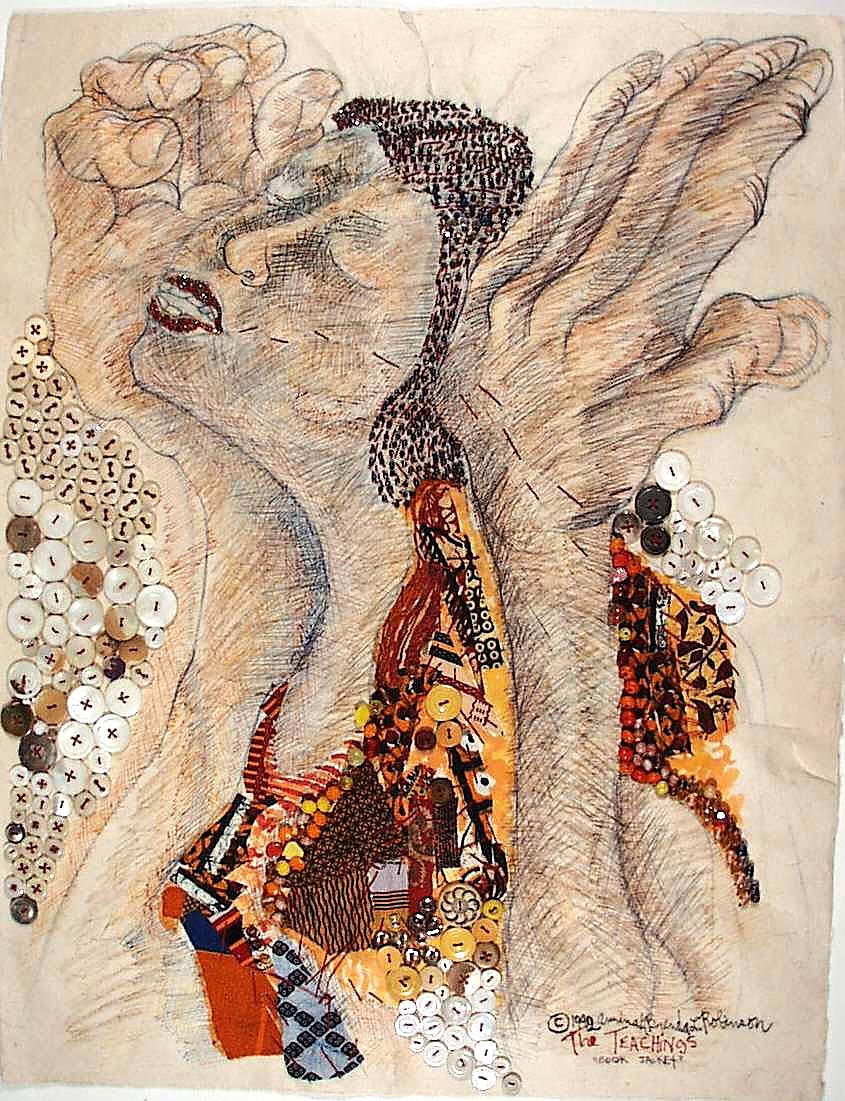

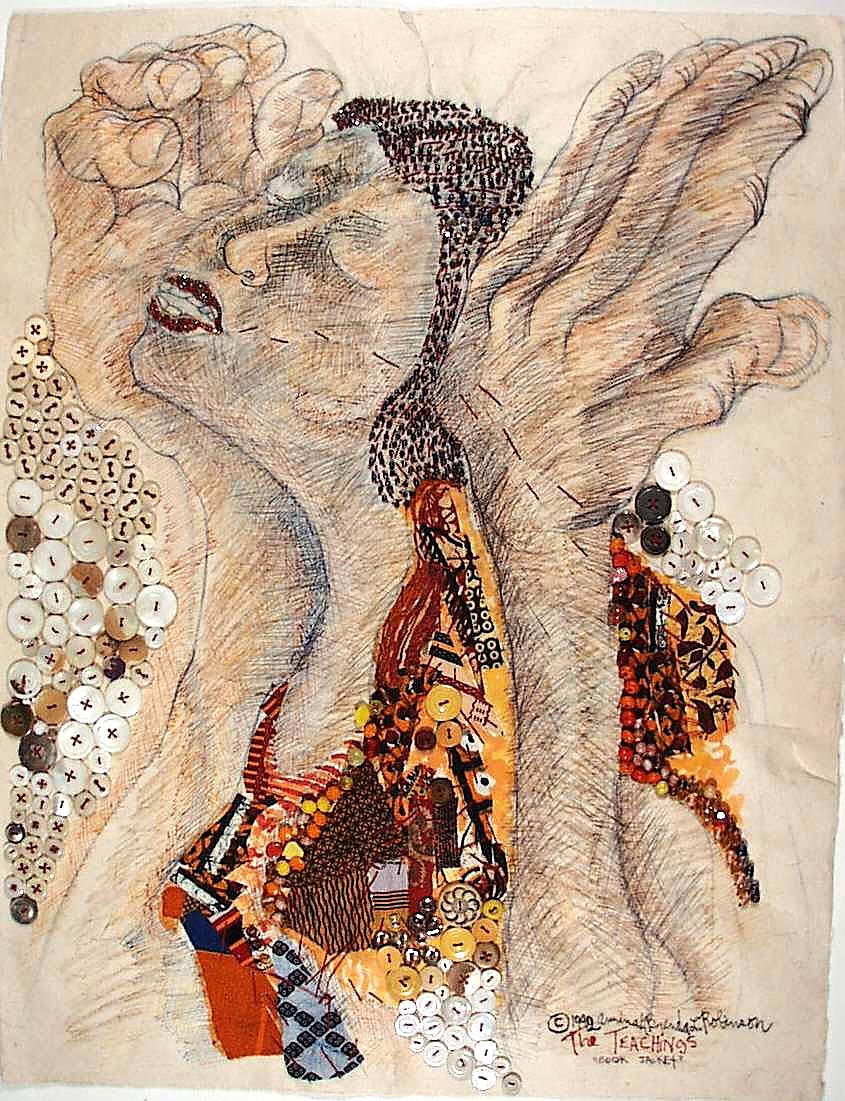

“The Teachings (Cover)” by Aminah Brenda Lynn Robinson, 1992, pen and ink and found objects. Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio: Gift of the Artist.

By Kay Koeninger

SPRINGFIELD, OHIO — The work of Aminah Robinson (1940-2015) is well known to many art lovers and museum visitors in Ohio, especially in her hometown of Columbus. A new traveling exhibition, “Aminah Robinson: Journeys Home, A Visual Memoir,” will make her work known to a larger national audience. This is fitting as her art, wide ranging in its use of materials and subject matter, is an eloquent and unique expression of the American experience. The exhibition, which was organized by the Columbus Museum of Art (CMA) and curated by CMA curator at large Deidre Hamlar, is on view at the Springfield (Ohio) Museum of Art until July 13 before traveling to the Newark Museum of Art and the Mobile Museum of Art. Two additional stops will be announced in the future, and the tour will last through 2028. Both the exhibition and tour are supported by the Art Bridges Foundation.

When Robinson was born in Columbus, just before World War II, it was a rigidly segregated city. She and her family lived in Poindexter Village, one of the first federally funded urban housing developments in the United States. It was a tight-knit community and Robinson often recalled that it provided her with a rich exposure to Black history, story-telling and visual creativity. In northern cities, strong community ties were crucial for Black Americans who had come from the South during the Great Migration. Both of her parents were artists who explored a variety of media, including drawing, collage, fabric and relief sculpture. Her father developed a mud-like material called “Hawgmawg” that added three-dimensional texture to two-dimensional works; later, Robinson often used this material in her own art. In addition to her parents, she also received instruction from other artists in the community.

Robinson, who lived in Columbus her entire life, started drawing at the age of three, though her formal training took place at the Columbus College of Art and Design, with further studies in art history and philosophy at The Ohio State University.

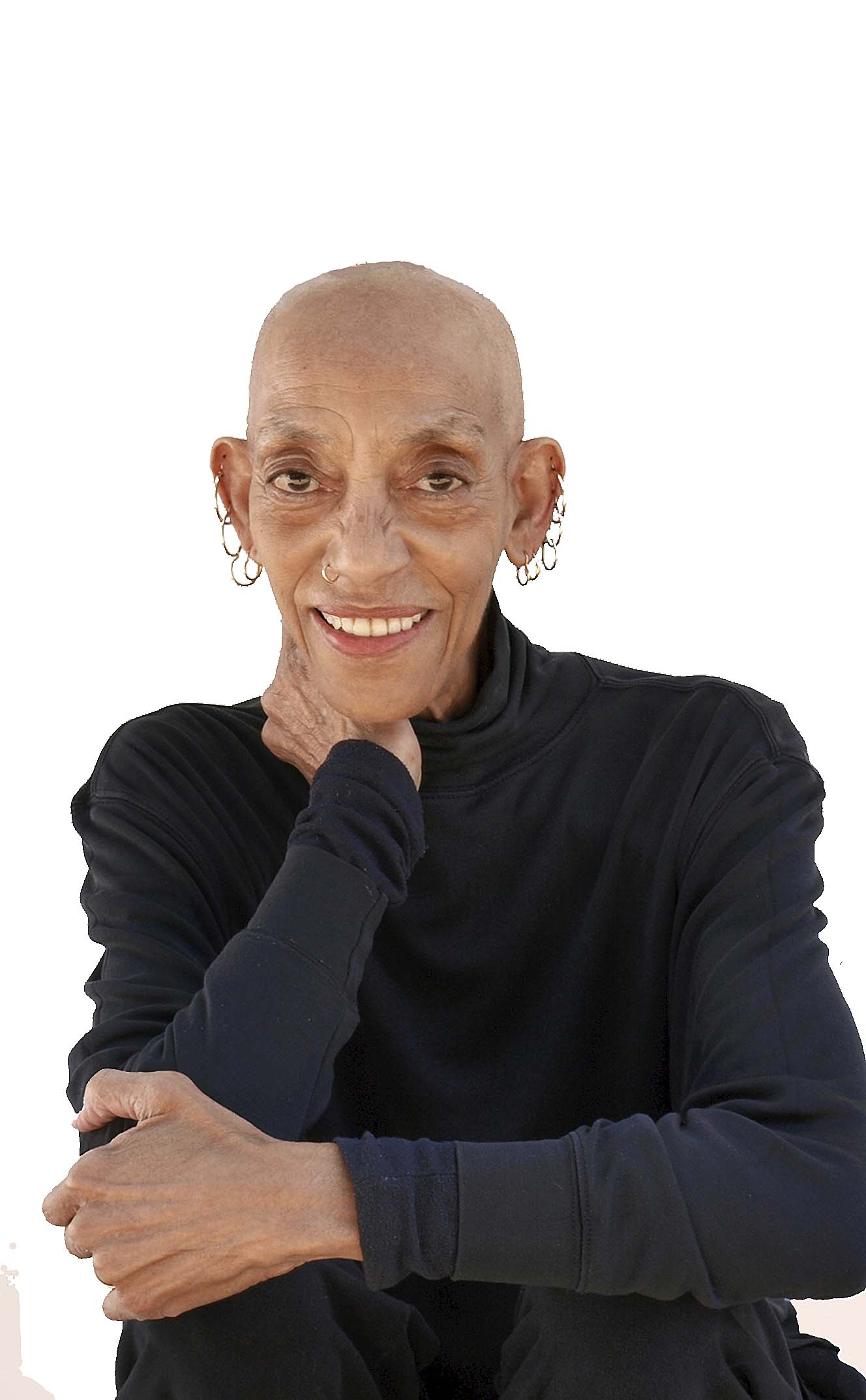

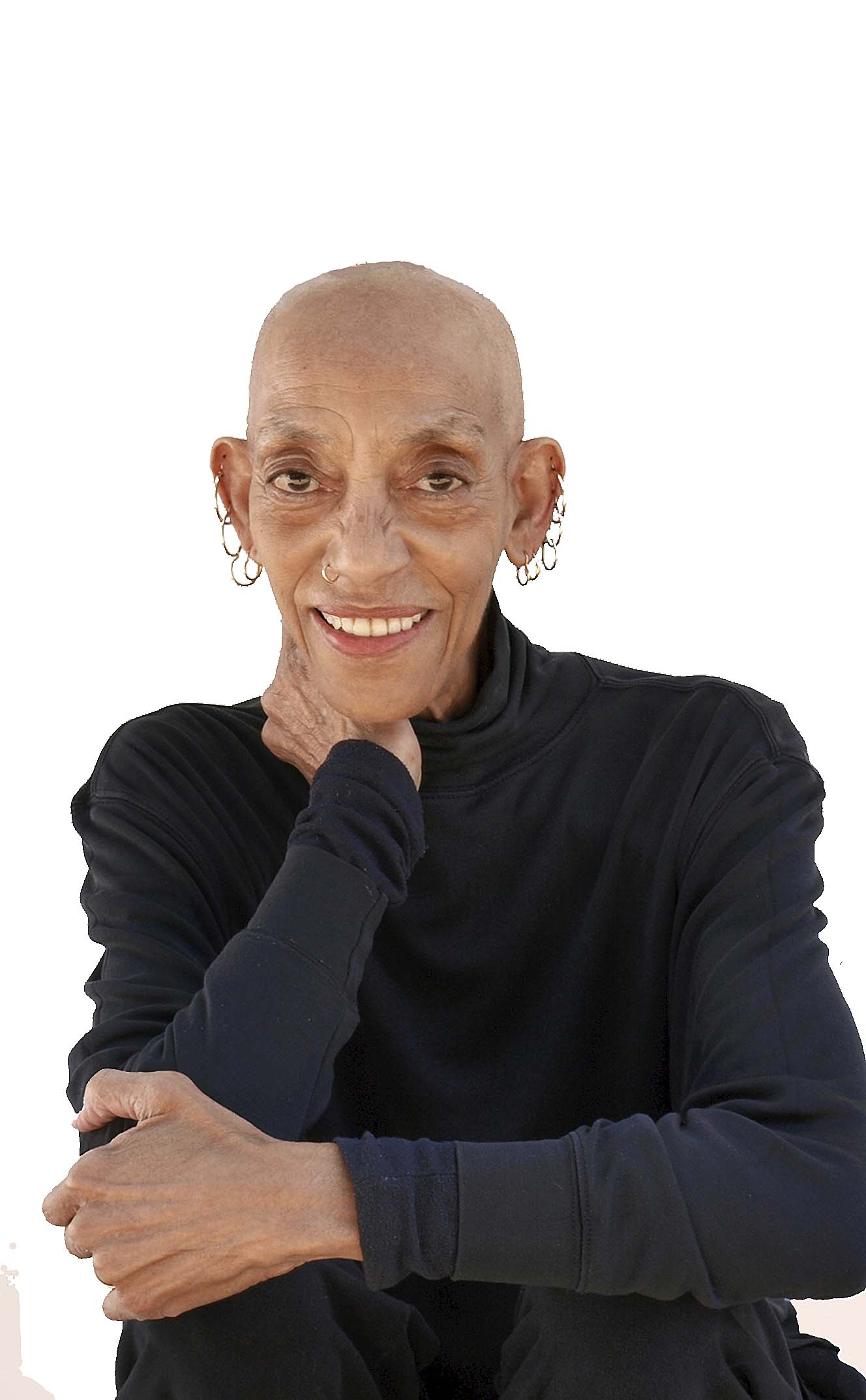

Aminah Brenda Lynn Robinson. Courtesy of the Columbus Museum of Art.

The complexity of Robinson’s large oeuvre can be explored through the term “syncretism,” which is often used in cultural studies. In terms of visual art, the term refers to the blending of elements of different cultures and movements to produce a new visual language. Despite being a Twentieth Century artist, many elements of Robinson’s art go back generations to their African source and are used in combination with Western (European-derived) materials and themes.

According to Harvard art historian and African Studies professor Suzanne Blier, qualities of African art include abstraction, asymmetrical balance and an emphasis on sculpture, human forms and collage or assemblage. These elements often appeared in Robinson’s work throughout her career.

Robinson’s early work in the exhibition shows evidence of her art school training in portraiture and uses traditional European materials. Untitled (Child and Malcolm) (1956) shows a poignant connection to Malcolm X, while “My Sister Sharron” (1950), is less detailed and more textural. “Self Portrait with Rabbit” (1959), shows masterful references to Surrealism, depicting a rabbit emerging from Robinson’s head.

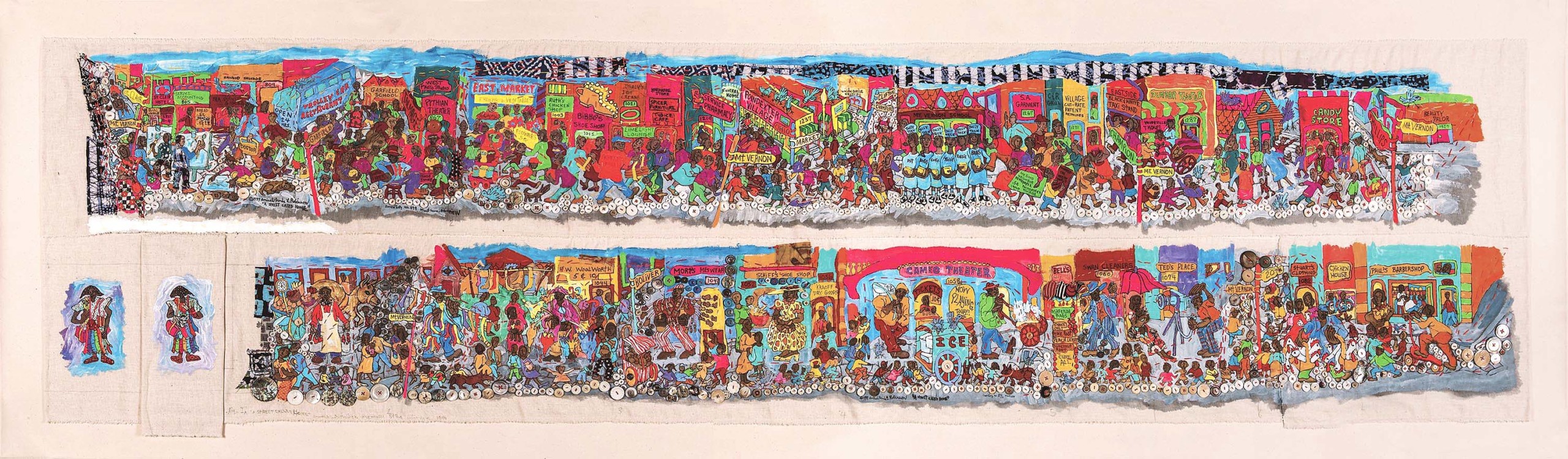

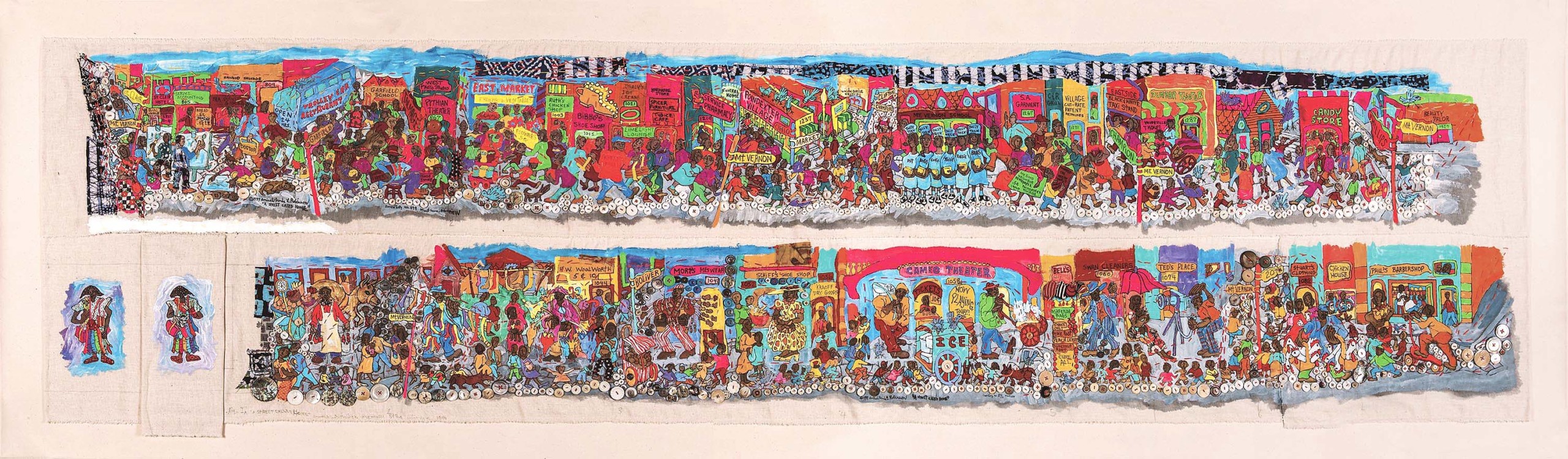

Robinson’s later paintings exploded into large-scale and colorful works, often in a horizontal format, with folk art touches and a unique use of non-traditional materials such as thread and buttons. They often celebrate the strong community of her family and friends in Poindexter Village. These important connections were crucial for Black Americans who uprooted themselves from the South to face the challenges of life in the North. “Christmas Day” (1982) shows a joyful family gathering whose details are highly linear; another holiday is celebrated in “Easter Egg Hunt” (1993). “A Street Called Home” (1997), is a tour de force of detail and color with literally hundreds of figures depicting the Black commercial center of Mount Vernon Avenue in Columbus. Robinson was a skilled textile artist and the composition is enriched by a rich border of a multitude of buttons.

“A Street Called Home” by Aminah Brenda Lynn Robinson, 1997, mixed media. Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio: Museum Purchase with funds donated by Wolfe Associates, Inc.

An important mentor to Robinson was Elijah Pierce, a well-known wood carver whose Columbus barbershop also served as his studio, gallery and a community center. Pierce is celebrated in several works in the exhibition. One, “Portrait of Elijah Pierce” (1974), is a lyrical portrait of the artist, almost dream-like in its effect with a strong sense of line, set in a background filled with Pierce’s art and barbering tools. Though executed in traditional materials — colored pencils and pastels — the use in this drawing of Pellon, a type of backing used in sewing and tailoring, demonstrates Robinson’s knowledge of fiber arts. Another tribute to Pierce is “A Holy Place” (1984-83), a highly detailed construction combining both two-dimensional and three-dimensional applications of fiber, found objects and buttons. Robinson called this type of construction a “RagGonNon” (from “Raggin’ On”), a reference to its use of fiber. To this viewer, the shape of the work, appropriately, recalls a hairbrush. The “holy place” depicted is, of course, Pierce’s barbershop.

It is in her unique sculpture that Robinson’s ties to African art become most apparent. Two sculptures in the exhibition were inspired by familiar figures of urban street life in the Black community in Columbus. “Organ Grinder” (1996), used an assemblage of a variety of materials — found objects, wood and fiber, as well as the clay-like “hogmawg” medium. It is both highly textural and abstract, with a touch of whimsey thrown in. “Sockman” (1980) is also characterized by a rich application of mixed media and has bundles of small relief figures on the base. This work recalls the detailed and encrusted mixed media sculptures of some African cultures. Both works have a strong presence.

“Sockman” by Aminah Brenda Lynn Robinson, 1980, wood, fabric, hogmawg and found objects. Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio: Gift of the Aminah Brenda Lynn Robinson Trust.

Many of Robinson’s works explore Black spirituality. Her aunt Themba was a formerly enslaved woman who left Sapelo Island, Ga., (south of Savannah) with other members of her family after the Civil War. She was the subject of Robinson’s “Themba: A Life of Grace and Hope” series, done between 1996 and 2012. In “Incantations” from that series, which is crafted from mixed media on paper, Aunt Themba raises her large, expressive hands in a pose of prayer or song. A respected elder, Aunt Themba was also known as a healer. At her side is another figure with an African mask as a head and other African masks are depicted throughout the composition, pointing to Robinson’s study of African art and travel in Africa. In The Teachings: Drawn from African-American Spirituals (1992), one of several books Robinson published, Black American spirituals, or hymns, are personified by women. In “The Teachings (Cover),” which served as the cover illustration for the book, a singing woman frames her face with her hands. The cloth of her dress recalls African textiles and is ornamented with a rich layer of buttons. Scholars note that large, strong hands are a characteristic of Robinson’s work and they recall a similar depiction of hands in the work of another Black American artist, Jacob Lawrence (1917-2000).

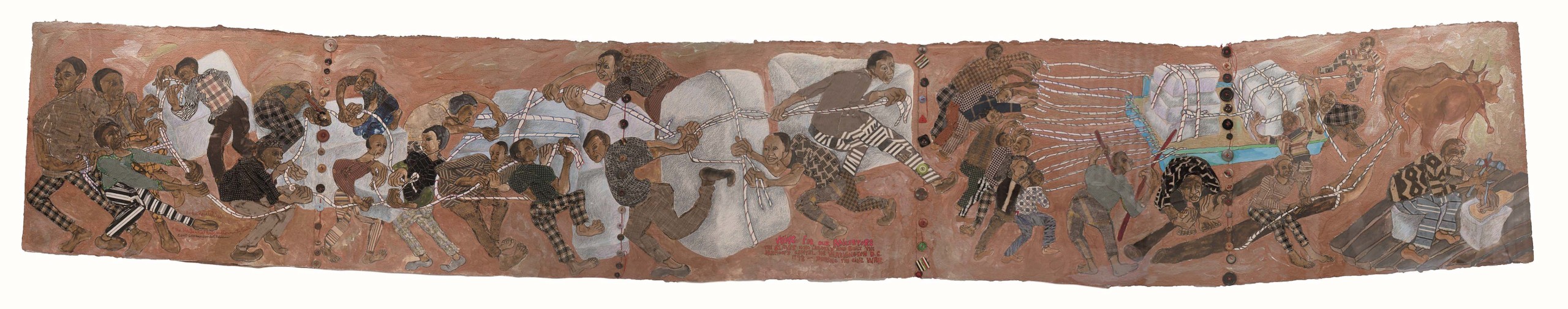

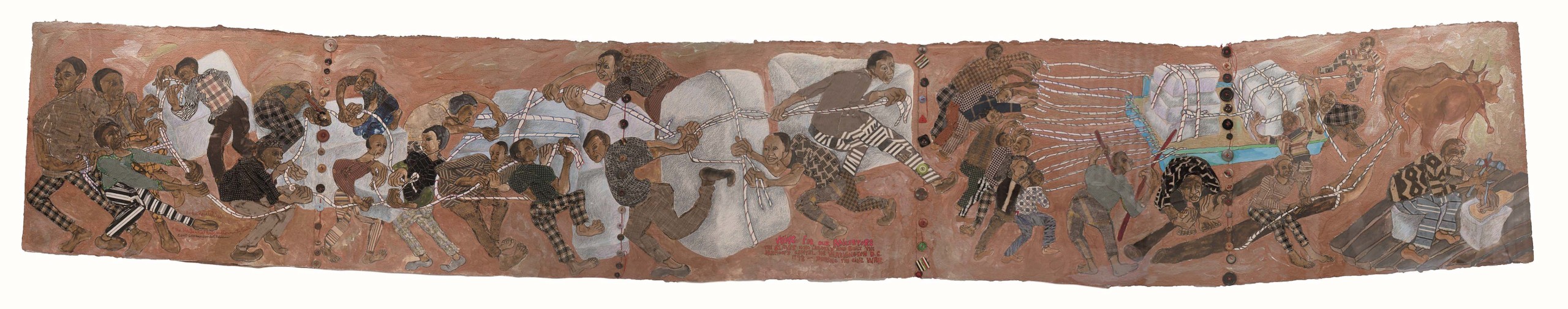

In addition to life in the North, many of Robinson’s works powerfully chronicle other aspects of Black history, including the horrors of the Middle Passage to America, slavery, Reconstruction and the Civil Rights era. “Presidential Series” is a group of paintings that honored President Barack Obama, his family and their ancestors. In this series, “Wings for our Ancestors: Slaves who Labored and Built the Nation’s Capital in Washington, DC” (2007-10), depicts workers hauling large stones for the US Capitol Building.

“Wings for Our Ancestors: The Slaves Who Labored and Built the Nation’s Capital in Washington, DC, During the Civil War (from the Presidential Suite)” by Aminah Brenda Lynn Robinson, 2007-10, rag painting: ink colored pencil, watercolor with fabric and buttons on heavystock. Columbus Museum of Art, Ohio: Gift of the Aminah Brenda Lynn Robinson Trust.

The effect of these works in a large exhibition format is one of exuberant color and texture. The narrative elements and overwhelming tactile richness are unique and are not often found in many works of contemporary art. It is highly appropriate that “Journeys Home” is part of the exhibition’s title. Aminah Robinson chronicles the epic journeys of her ancestors — including the Middle Passage and the Great Migration. She also records her own journeys, whether to Africa or along Mount Vernon Avenue in Columbus, Ohio. And, implied in all aspects of her artistic life is the hope — heartbreakingly relevant for our time as well — that all journeys lead to home.

The Springfield Museum of Art is at 107 Cliff Park Road. For more information, 937-325-4773 or smoa@springfieldart.net.