By Terrilyn Simpson

He restored his first antique when he was ten. He went on to restore well over 10,000.

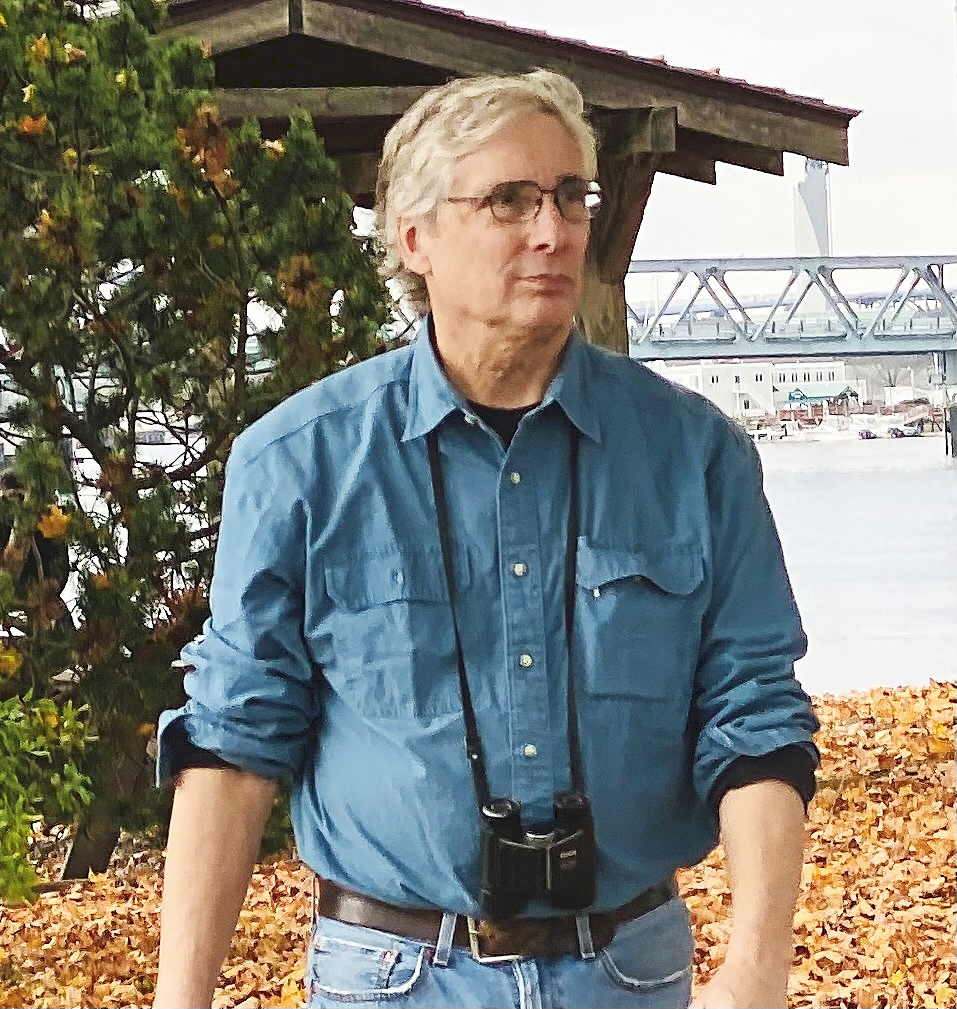

Stephen Wright Weston unexpectedly suffered a fatal heart attack on February 4, at his Winthrop, Maine, home. He was a seventh generation Mainer, born on March 22, 1951 in Caribou, Maine, to Donald and Theodora Weston.

He grew up in Winterport, Maine, attended both Bangor and Brewer High Schools and initially entered the University of Maine to follow in the engineering footsteps of his father and other male family members but soon found it didn’t fit. So he headed a little south, to Winthrop, bought a small 1830s cape and began discovering what things had been and proving what they could again become.

He opened the doors of his furniture restoration business when he was 20. He never ran an ad; he never hung a sign and for a long time, he didn’t list a phone number. Word of his work spread rapidly and within weeks he was, he once recalled, swamped with work. He almost immediately branched off into house restoration and through the years, disassembled and saved all, or parts of, 20 Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century houses that would otherwise have been razed, rebuilding and restoring many of them, including the one in which he last resided. He surrounded his 1842 home with historically accurate flower gardens.

His knowledge and expertise in furniture restoration and preservation, said one antique dealer who became a customer when Weston was just 22, was intrinsic, his skill, nearly unfathomable. He received calls from all over the country, routinely did work for dozens of antique dealers in Maine and other parts of New England, and did work for museums and historical societies statewide, including extensive restoration and exhibitions for the Maine State Museum and for both the private and public rooms of the Governor’s Mansion. He helped conceptualize and created the Nineteenth Century cabinetmaker’s shop for the Maine state museum’s permanent exhibit and wrote a chapter on Nineteenth Century paint methodology for the state museum book on design and color. Throughout his career, he made all his own paints and finishes. He taught a class at the American Museum of Folk Art in New York City on Nineteenth Century paint designs. And he restored premier exhibit pieces by the Herter Brothers, prominent Nineteenth Century furniture designers and decorators, for a major exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

He once routinely categorized his conservation accomplishments as merely preserving his own heritage.

He was a voracious reader, referring to his extensive library and study of the 1800s as “reading the Nineteenth Century.” He was an accomplished birder who, after reporting the discovery of a white robin at his yard feeder at the age of 10, was invited to participate in a university birding group. He later sculpted the white robin in wood. For several years he published a Maine birding magazine. He had a lifelong passion for stamp collecting and an extensive knowledge of early glass which he meticulously collected throughout his adult life.

Separate from his career as a conservator, and less well known, was his extensive work as an artist. His daily entries into several hundred notebooks contain an endless array of solved equations to facilitate the creation of his elaborate sketches, many of them now materialized in paintings, wooden sculptures and whimsical items of furniture and everyday objects. Artist Eric Hopkins, a longtime close friend, described Stephen as a “brilliant, creative genius — a true Maine Yankee Renaissance man.”

In recent years he had become passionate in researching the genealogy of his maternal ancestors in the Walpole, N.H., area and had hoped to spend extended time there. Some of his cremated remains will be distributed there in the upcoming summer.

He is survived by his longtime partner, Terrilyn Simpson of Winthrop.

A memorial service, to be announced, will be held in the late spring.