“View on the Stour near Dedham” by John Constable (British, 1776–1837), 1822, oil on canvas, 51 by 74 inches. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

by Jessica Skwire Routhier

SAN MARINO, CALIF. — Recent years have witnessed a trend of museum exhibitions that examine intersections between Anglo American art and the ecological sciences, including “Nature’s Nation” at the Princeton University Art Museum (2018-19) and “Alexander von Humboldt and the United States” at the Smithsonian American Art Museum (2020-21). “Storm Cloud: Picturing the Origins of Our Climate Crisis” builds on those earlier efforts in part by broadening the material to include visual culture of all varieties and expanding the geographical scope from London to Jamaica to Los Angeles. Organized by The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens in San Marino, Calif., in conjunction with the J. Paul Getty Museum’s regional initiative “Pacific Standard Time (PST),” ”Storm Cloud” is on view at the Huntington September 14 through January 6.

The show begins and ends with London, not only with respect to the exhibition’s layout and chronology but also in terms of its conceptualization. In considering how the Huntington would respond to PST’s theme of “art and science collide,” co-curators Melinda McCurdy (the Huntington’s curator of British art) and Karla Nielsen (senior curator of literary collections at the Huntington’s library) were inspired by the Huntington’s own collection, which makes up about 80 percent of the works on view. Among its strengths are significant holdings by British artist and writer John Ruskin, neatly dovetailing the two curators’ areas of expertise.

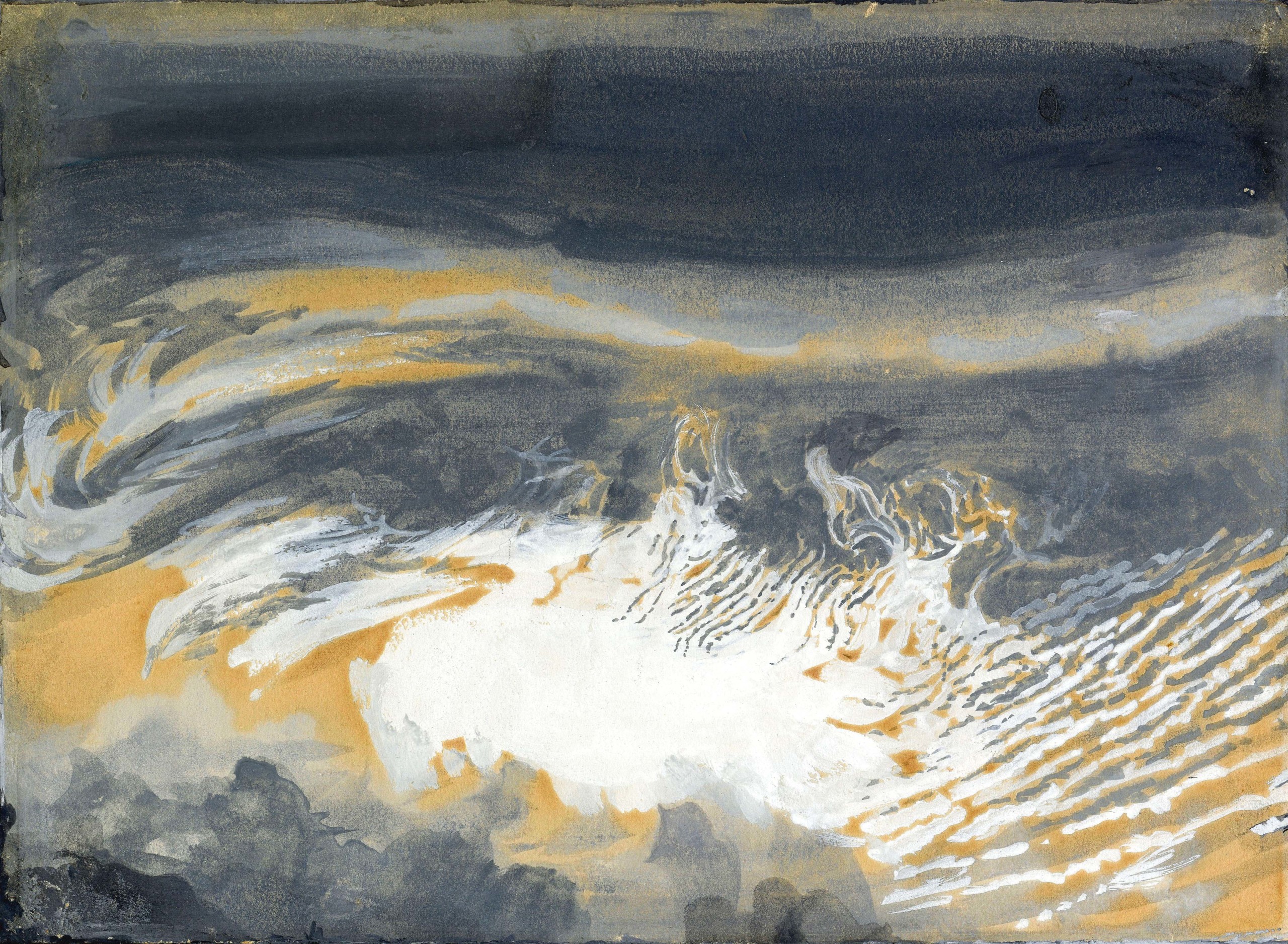

The exhibition’s name comes from a series of slide lectures Ruskin presented in London in 1884, in which he drew on decades of observation of the sky to argue that it had, in fact, changed over the course of the years. Near the entry to the exhibition are representative images that Ruskin used in his lectures, along with a period projector. Ruskin’s — and London’s — anxieties about the atmosphere’s degradation from the effects of big industry were also felt a continent away, as a rapidly developing Los Angeles increasingly grappled with smog and other air-quality issues. The curators have made explicit the connection here to the clean-air activism of Nineteenth Century Britain. Although the last section of the show takes the visitor to 1930s California, it incorporates a collection of objects grouped under the theme of “London Fog,” including a printed version of Ruskin’s lecture and some of the cloud studies he made that preceded it.

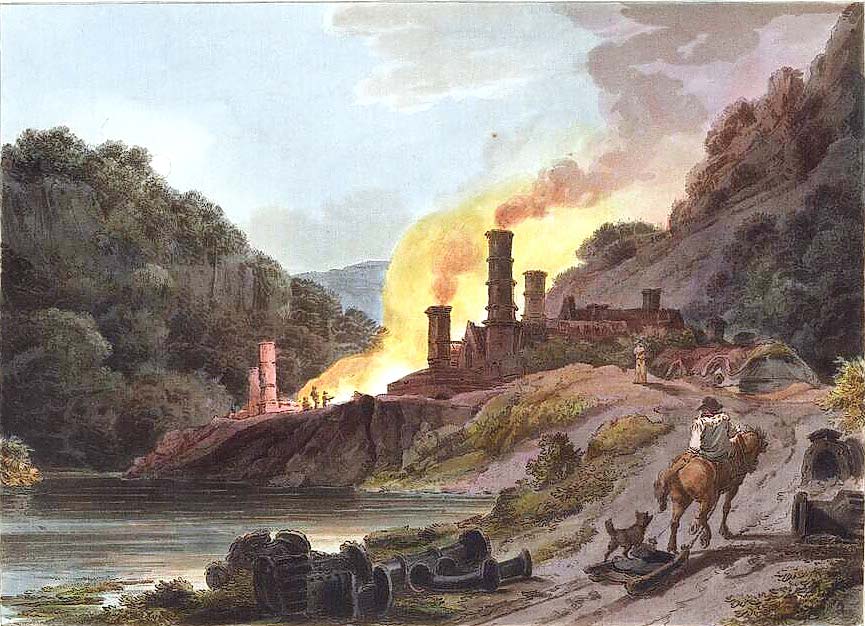

“Iron Works of Coalbrook Dale” in The Romantic and Picturesque Scenery of England and Wales by Philippe Jacques de Loutherbourg (French‐British, 1740–1812), 1805, aquatint in printed book, 15¾ by 11-3/8 inches. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

“[Ruskin] was an advocate for close observation of nature and depicting things as you observe them,” says McCurdy, and this is a thread that runs throughout the exhibition. The show is divided broadly into three “thirds”: the first, Nielsen says, “overviews the sciences that come into shape in the Nineteenth Century through which human impact on the environment is traced.” This acceleration of scientific activity occurred alongside the simultaneous rise of the Industrial Revolution and the Romantic movement, in which, McCurdy says, “people are becoming much more personally invested in the natural world.” Here are not only Ruskin but also writers Dorothy and William Wordsworth, Alfred Tennyson and Henry David Thoreau, as well as painters Thomas Cole and John Constable, the latter well represented at the Huntington with the monumental “View on the Stour Near Dedham” from 1822.

The middle section of the exhibition, McCurdy says, “deals with the ways that certain political and economic forces in the Nineteenth Century began to contribute to a climate crisis; so, for example, empire building and colonialism and with that the rise of the economy of enslavement.” Another strength of the Huntington’s collections is material related to “the British colonial enterprise in Jamaica,” and the curators have supplemented those maps, books, prints, documents and drawings with the loan of Frederic Edwin Church’s massive “Vale of St. Thomas, Jamaica” from the Wadsworth Athenaeum. The spectacular canvas captivates the eye but, on close inspection, reveals flaws in the Edenic landscape it represents. “Underneath that beautiful sunlit rain cloud that you see is a landscape which is dry, it’s deforested,” McCurdy points out. “This was a result of the timber needed to work the sugar mills and the plantations,” McCurdy adds, and thus Cole’s canvas demonstrates, if only obliquely, “how monocrop agriculture is devastating not only to the people who are forced to work and make it happen but also to the environment in which it occurs.” Another standout in this section is a series of drawings by Mary Clementina Barrett, the wife of a British planter and enslaver, which reveal the dispassionate way in which colonial landholders viewed enslaved workers as more or less just part of the landscape.

“Vale of St Thomas, Jamaica” by Frederic Edwin Church (American, 1826–1900), 1867, oil on canvas, 48-3/8 by 84-5/8 inches. Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Conn. The Elizabeth Hart Jarvis Colt Collection. Image courtesy of the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art.

This section of the exhibition also addresses the plantation system in the Southern United States, particularly cotton farming, with works by Winslow Homer, Lewis Hine and others. This is another connection to Britain, whose textile industry depended on those imports. The availability of cheap American cotton and the rise of specialized machinery to process it led to labor and industrial rebellions overseas; here, for instance, we also see an array of works by design revolutionary and labor activist William Morris, another luminary of the Huntington’s museum and library collections.

The third and final section of the exhibition, as noted above, brings us to the Western United States, with works by famed survey photographers Carleton Watkins and Timothy O’Sullivan as well as spectacular Western landscape paintings. Andrew Melrose’s “Westward the Star of Empire Takes Its Way — Near Council Bluffs, Iowa,” lent by the Autry Museum of the American West, commemorates the moment when the transcontinental railroad was completed, unifying the country by bringing people, products and raw materials from one coast to the other. Natural resources are a focus of this final third of the exhibition, including not only a section dedicated to the rise of the petroleum industry (on whose wealth both the Huntington and Getty Museums were built), but also a series of works addressing the Los Angeles aqueduct project that diverted the Owens River to supply water to that city. Photographs and writings by Mary Hunter Austin, including her renowned book The Land of Little Rain, document the area’s landscapes and waterways, including their use by both Indigenous Peoples and settlers from the East.

Nielsen points out that three river stories twine throughout the exhibition, including not only the Owens River and Constable’s Stour River but also the Concord River in Massachusetts, which Thoreau traveled, fished and documented throughout his lifetime. “He was very interested in the changing flows of the Concord River,” she explains. “Farmers had depended on the seasonal flooding of the riverbanks to do their work for decades, and Indigenous food practices had been along the riverbanks, but then that water was fantastic for mills and so the river starts to run on ‘factory time,’” which Thoreau found “alarming.” His seven-foot-long hand-drawn map of the river, borrowed from the Concord Public Library, is on view alongside his walking stick, notched at one-inch intervals to mark the depth of snow and water. Thoreau also assiduously observed the plant life of the Concord River Valley, collecting specimens for an herbarium and developing a list of leafing and blooming times. In an essay for the book that accompanies the exhibition, Boston-based biologist Richard Primack conducted a follow-up study, sending students out to collect the same information from our present moment and compare it to Thoreau’s data. Concord’s plants, they found, are leafing and blooming earlier now in response to warmer temperatures.

McCurdy says that she and Nielsen both “learned a lot” from the contributors to the book, who include a number of non-art-historians from a variety of fields. In addition to the main essays by McCurdy and Nielsen, Nicholas Robbins, and Kristen Case, 15 individuals were tapped to write brief entries on single objects in the show. As an example, McCurdy points to Jan Zalasiewicz, a paleobiologist who is part of the Anthropocene Working Group, which is attempting to pin down, historically and scientifically, the moment when human impact on the earth’s ecology hit a tipping point. Zalasiewicz’s essay is about a stratigraphic map of England and Wales, but he also provided valuable commentary on William Dyce’s painting of Pegwell Bay in Kent, which shows geological layers in a cliff overlooking a beach populated by fossil collectors. Zalasiewicz ended up writing some of the interpretive text for this painting that visitors will see in the exhibition.

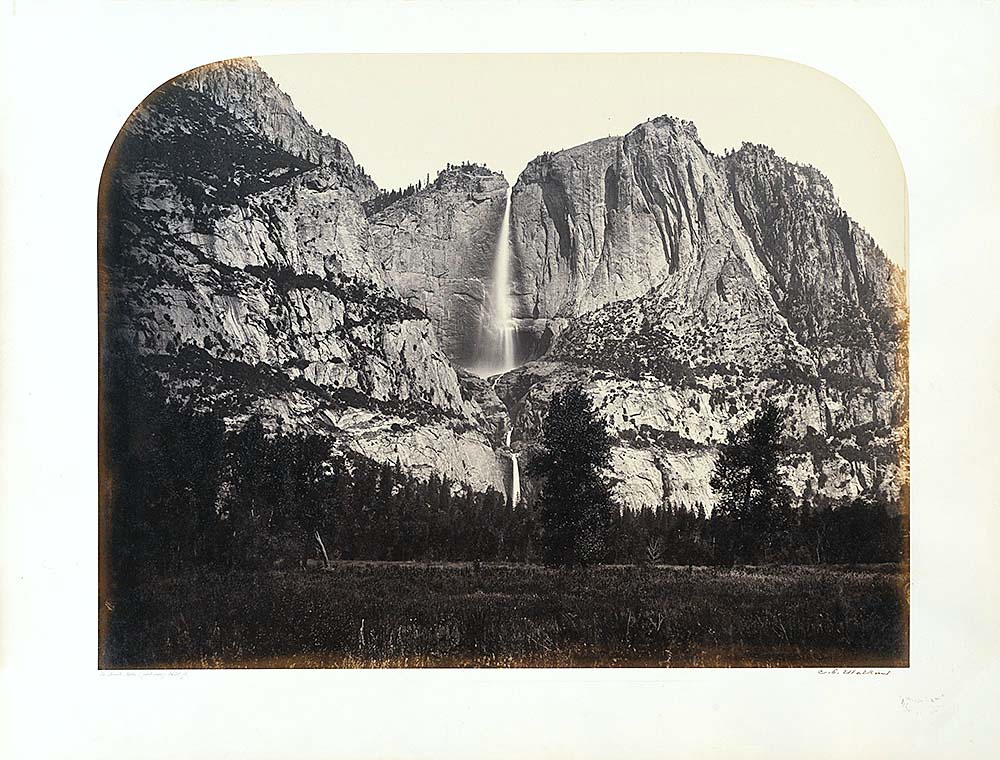

“Yosemite Falls ‘front view’” (plate 30) in Yosemite Valley/Photographic Views of the Falls and Valley of Yosemite in Mariposa County, California, by Carleton Watkins (American, 1829–1916), 1861, albumen print, 19¾ by 25-5/8 inches. The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens.

Tapping outside knowledge gave McCurdy and Nielsen the chance to work with materials that are normally outside their purview at the Huntington. To illustrate the development of paleontology and the evolving understanding of extinction, they borrowed numerous fossils from the Los Angeles Museum of Natural History and examples of hats made from bird feathers (or whole birds) and the pelts of beavers. McCurdy tells a wonderful story about how a visit to Brantwood, Ruskin’s home in England’s Lakes District, brought to light a very specific rock that Ruskin had collected and then carefully illustrated for volume four of his art treatise Modern Painting. The rock and the book are both on view in “Storm Cloud,” next to a painting by John Everett Millais that features a nearly identical rock, rendered in meticulous detail.

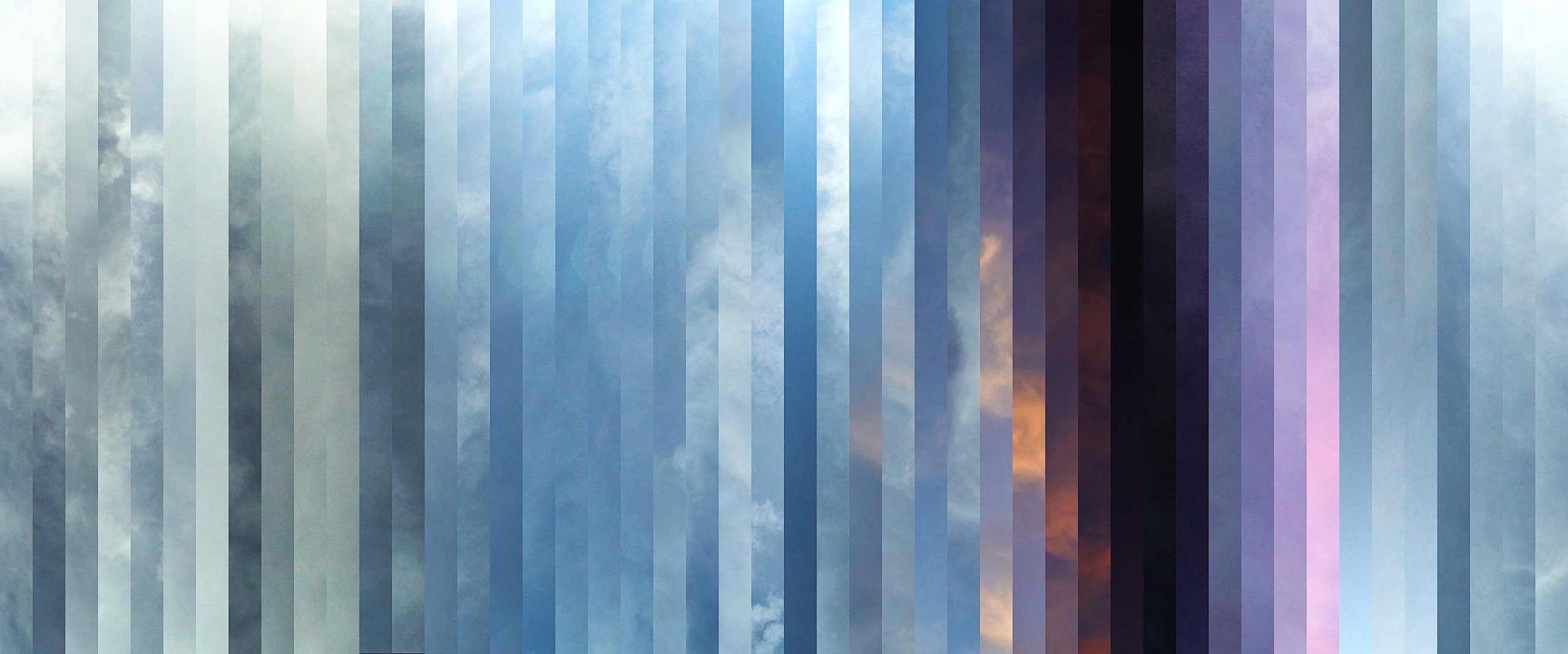

The curators also branched out from their more historical disciplines by including the work of five contemporary artists, spread throughout the show. Binh Danh, Leah Sobsey and Will Wilson’s photographic images re-envision the tradition of Western survey photography and botanical specimen collection; Jamilah Sabur’s diptych and poem lament the ecological and human toll of mining in Jamaica; and Rebeca Méndez’s video projection, which ends the show, splices together prolonged recordings of the sky, coming full circle with Ruskin’s lantern slides that gave the exhibition its name.

A recurring theme of the show, says Nielsen, is “this combination of precision and measurement as a way to feel connected to the natural world, as a way in when one feels alienated from it.” She sees this specifically in Thoreau’s example but also, more broadly, in the very intersections of art and science that PST has been designed to explore. It is, for instance, no mean feat to untangle the cords of mutual influence when it comes to Constable’s cloud studies and the work of early meteorologists who were also obsessively watching the sky. “Storm Cloud,” then, is a well-chosen theme and title for this gathering of big ideas and big observations — all of them too big to ignore.

The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens are at 1151 Oxford Road. For information, www.huntington.org or 304-529-2701.