Edith Halpert at the Downtown Gallery, in a photograph for Life magazine in 1952. She is joined by some of the new American artists she was promoting that year: Charles Oscar, Robert Knipschild, Jonah Kinigstein, Wallace Reiss, Carroll Cloar and Herbert Katzman. Photograph ©Estate of Louis Faurer.

By Laura Beach

NEW YORK CITY – “Occasionally an art dealer comes along who plays such a transformative, crucial role in the development of art and artistic movements that his or her contributions call for celebration and study. In the United States, such art dealers as Alfred Stieglitz, Betty Parsons, Leo Castelli and Ileana Sonnabend served as mentors to countless contemporary artists in their time, and their galleries were incubators of the avant-garde. Edith Halpert is such a figure. She made vital contributions to the growth and even the definition of American art,” Jewish Museum director Claudia Gould writes in her foreword to Edith Halpert: The Downtown Gallery and the Rise of American Art, the catalog accompanying an exhibition of the same name at the Jewish Museum through February 9.

Organizing curator and catalog author Rebecca Shaykin began thinking about Halpert (1900-1970) – a Russian Jewish immigrant and champion of American art, both folk and Modern, who founded New York’s influential Downtown Gallery – slightly more than a decade ago, after reading journalist Lindsay Pollock’s biography of Halpert, The Girl with the Gallery. “Halpert’s story, one of a successful woman in the arts, really spoke to me. After working with curator Mason Klein on the 2014-15 show ‘Helena Rubinstein: Beauty Is Power,’ about another tour-de-force businesswoman, it made me think Halpert could be the center of an exhibition here.”

Shaykin believes history has not given Halpert her full due. Halpert might have agreed. Speaking at a conference in 1950, nearly two and a half decades after she opened the Downtown Gallery, Halpert complained good-naturedly that dealers’ contributions are often overlooked. Still, it is a stretch to say that Halpert is “all but forgotten.” She is regularly cited in artists’ monographs and single-owner collection catalogs. In addition to Pollock’s biography, which emphasizes the fine arts, A Kind of Archeology: Collecting American Folk Art, 1876-1976 and Making It Modern: The Folk Art Collection of Elie and Viola Nadelman explore the dealer’s role in shaping the market for American folk art.

What Shaykin does in a way no one else has is weave the disparate strands of Halpert’s career into a cohesive whole. She does this visually, by arraying in the Jewish Museum display roughly 100 immensely satisfying works of art, all from Halpert’s inventory or private collection. She does it archivally by studying the dealer’s detailed records, now mainly at the Archives of American Art. Shaykin’s 1926-1968 timeline of Downtown Gallery exhibitions offers a concise summary of the scope, trajectory and originality of Halpert’s accomplishment.

So what made Halpert so successful? “Oh, goodness. There are so many reasons,” says Shaykin, enumerating Halpert’s most salient qualities: an impeccable eye and a knack for spotting talent; and exceptional business acumen, honed in retailing and banking even before she opened the Downtown Gallery. Shaykin adds, “She was savvy with money and knew how to run a business. She had a strong sense of design and pioneered the presentation of Modern and Contemporary art in a way we take for granted today.”

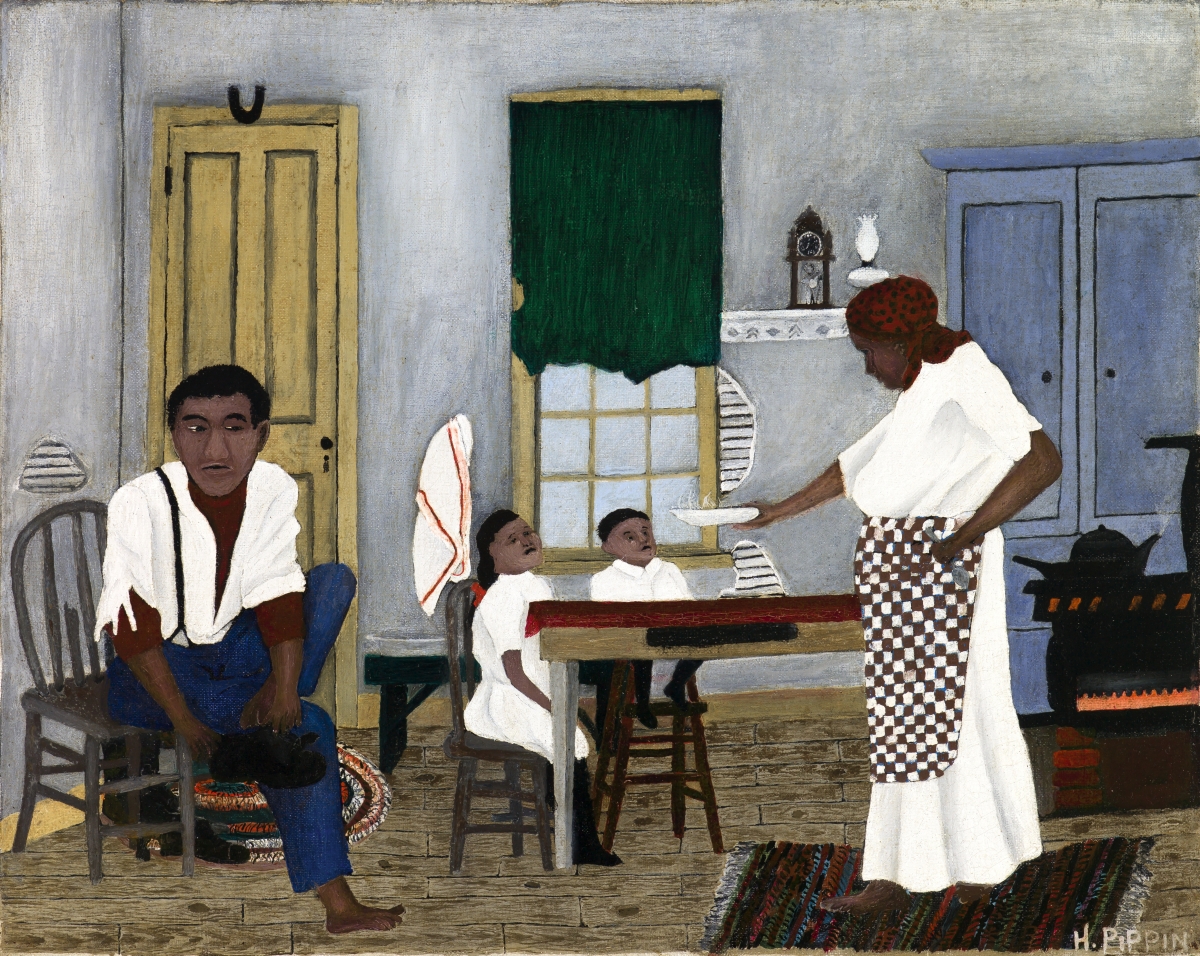

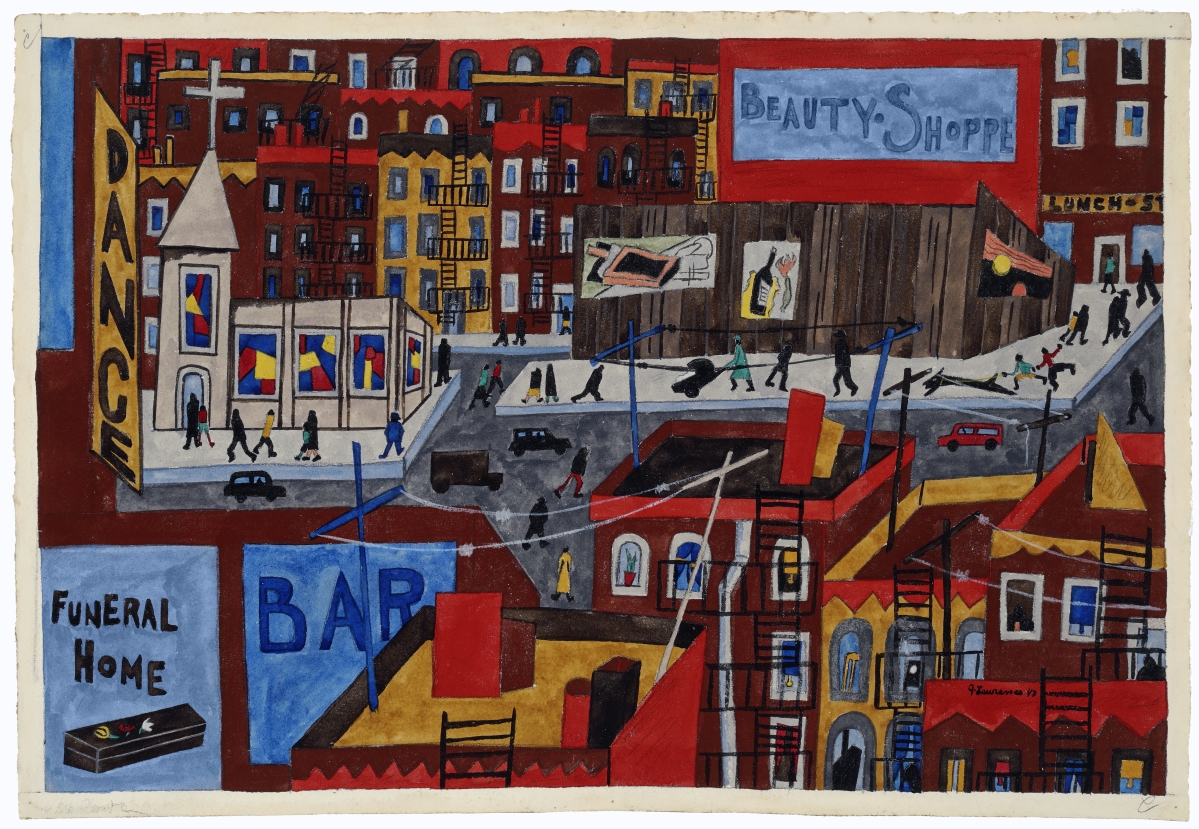

Crucially, Halpert never stopped asking what is American about American art. For her, the answer was deeply rooted in her social and political convictions. She took the words E pluribus unum – out of many, one – to heart, orchestrating shows that emphasized diversity, tolerance and inclusion. As Shaykin records, Halpert championed the art of women, immigrants and African Americans. In 1942, she rallied to the defense of Japanese American painter Yasuo Kuniyoshi, classified an enemy alien during World War II, with a retrospective loan exhibition of his work.

Crucially, Halpert never stopped asking what is American about American art. For her, the answer was deeply rooted in her social and political convictions. She took the words E pluribus unum – out of many, one – to heart, orchestrating shows that emphasized diversity, tolerance and inclusion. As Shaykin records, Halpert championed the art of women, immigrants and African Americans. In 1942, she rallied to the defense of Japanese American painter Yasuo Kuniyoshi, classified an enemy alien during World War II, with a retrospective loan exhibition of his work.

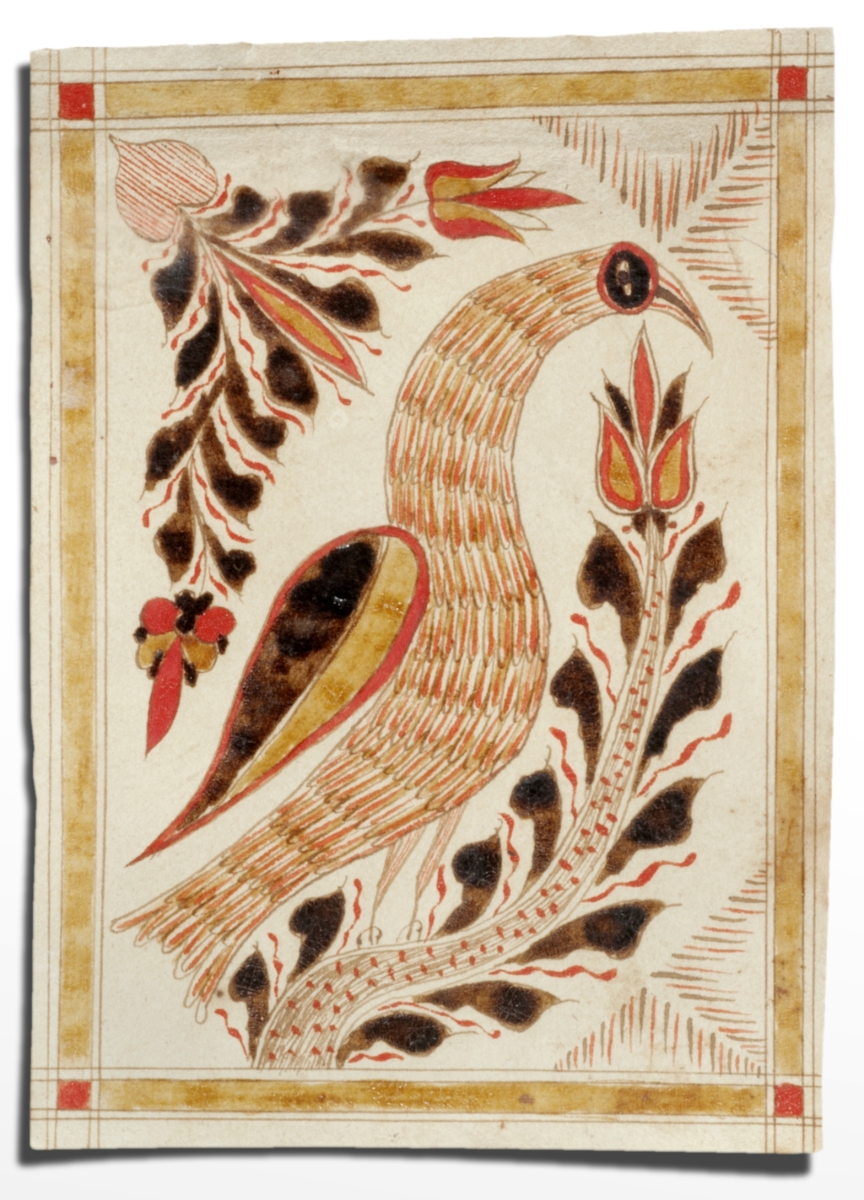

Halpert sought to demolish class barriers, sometimes with mildly amusing results. In an “Upstairs Downstairs” twist, folk art filled the second floor of her 13th Street gallery. After moving to midtown Manhattan in 1940, she reversed the equation, showing folk art on the first floor as a preliminary to viewing Modernist work in the space above, a juxtaposition meant to encourage visitors to think about the DNA of American art.

Her egalitarian instincts prompted her to seek ways to make art affordable and accessible for Americans of all means. She did this most notably between 1927 and 1934 with annual exhibitions of American printmaking. In some ways these initiatives were little more than window dressing. In truth, wealthy clients such as Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, who spent $20,000 on folk art with Halpert in 1928 alone, kept the gallery afloat in its early years.

Her salesmanship, as Shaykin describes it, was “theatrical.” The Exhibidor, a revolving panel Halpert invented for showing artwork to clients, evokes memories of the rotating stages later used by auction houses. Halpert’s marketing schemes were ingenious. “She wasn’t afraid to have fun,” says Shaykin. Every dealer knows the frustration of owning a great piece that fails, inexplicably, to sell. Halpert acted on those feelings, in 1941 organizing passed-over pieces into the show “What Is Wrong with This Picture?” It “should make the critics and museums and collectors blush,” the dealer said at the time. In 1952, her exhibition “Art for the 67%” targeted married couples, who accounted for two-thirds of the adult population, offering for sale pictures for “Mister” and “Missus.”

In 1963, Halpert organized “Signs & Symbols U.S.A. 1780-1960,” examining the affinities among folk, early Modern and Pop art. Ever current if no longer cutting edge, the dealer had paved the way for a new group of tastemakers, among them Betty Parsons, whose gallery opened in 1946, and Sidney Janis, who debuted as a dealer in 1948.

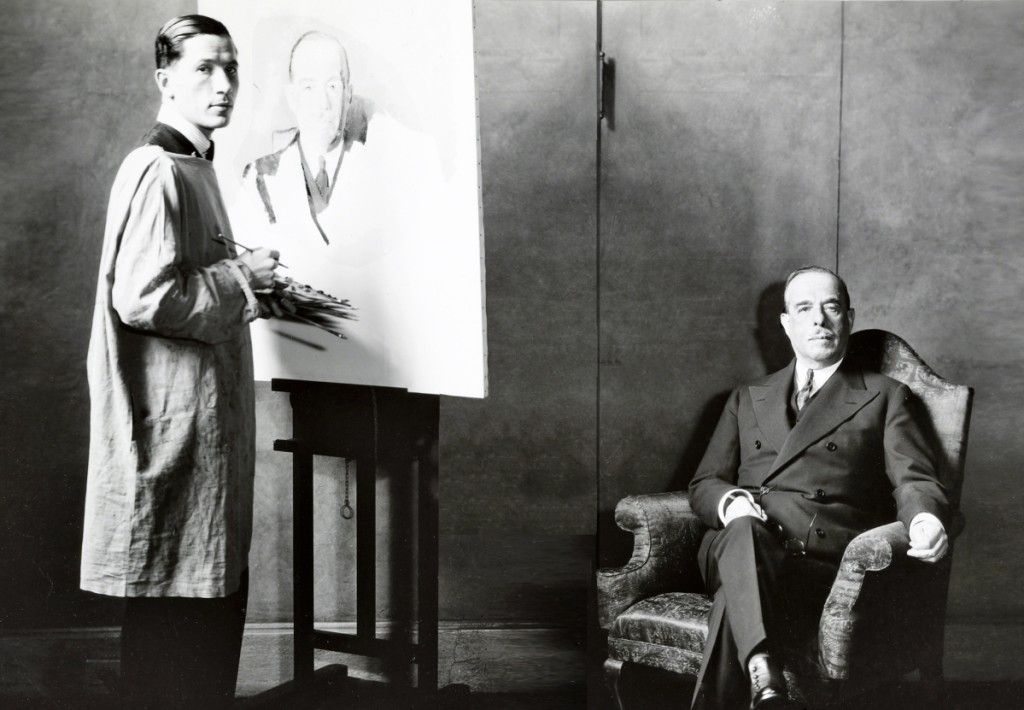

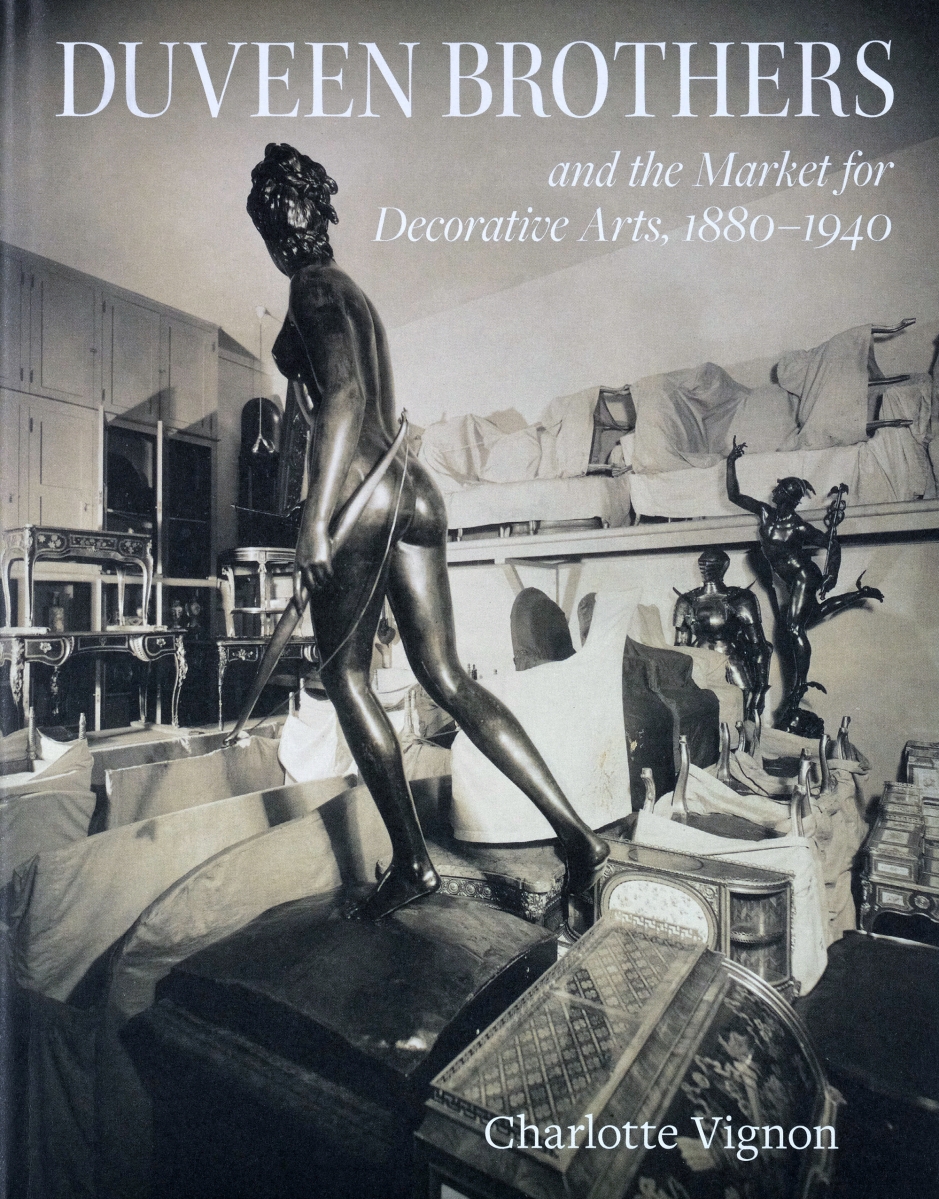

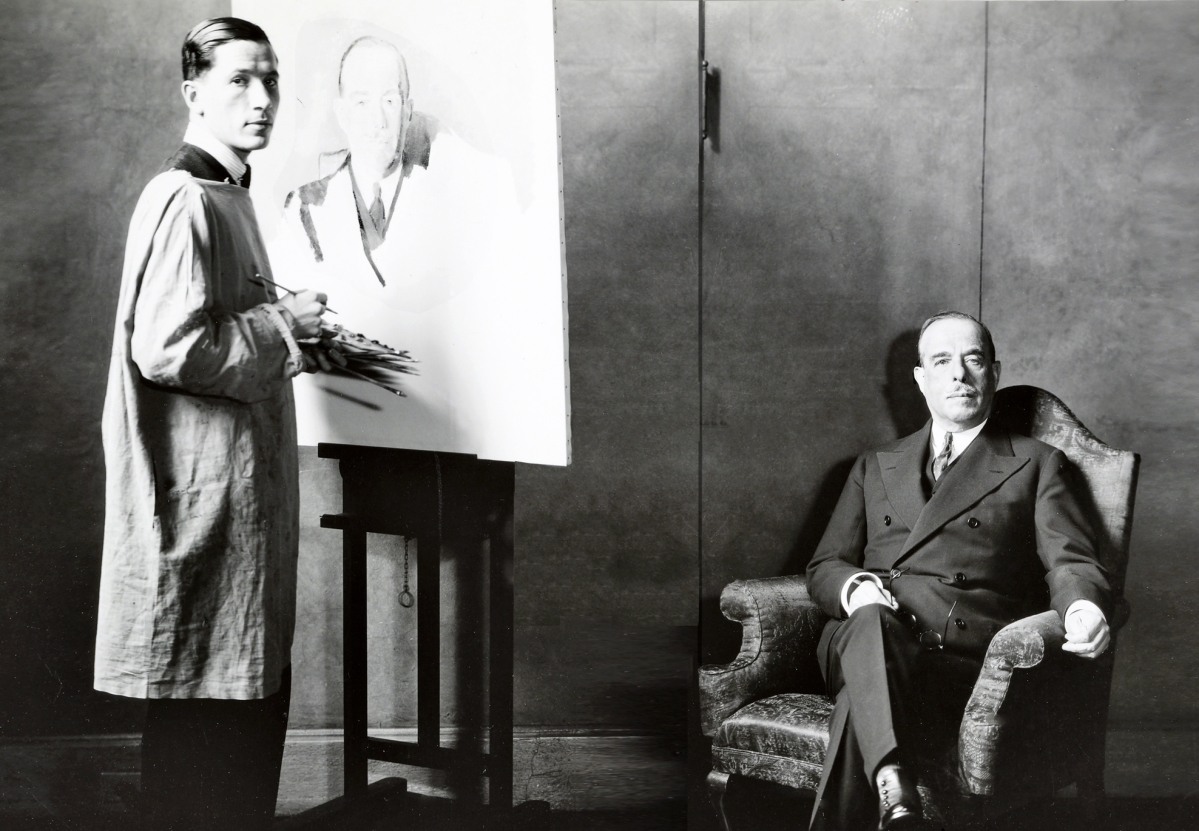

An undated photograph of a showroom of Duveen Brothers Gallery at 720 Fifth Avenue, New York City. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles.

In Duveen Brothers and the Market for Decorative Arts, 1880-1940, Charlotte Vignon, curator of decorative arts at the Frick Collection and visiting associate professor at the Bard Graduate Center in New York, reveals the workings of the foremost dealer in European art and antiques in London, Paris and New York in the first half of the Twentieth Century. Though not a breezy read – for more sensational accounts of the colorful Joseph Duveen (1869-1939), a.k.a. Baron Duveen of Millbank, see popular biographies by Samuel N. Behrman and Meryle Secrest – Vignon’s treatise is nevertheless an indispensable companion to other studies of the era’s great collections and collectors, from Benjamin Altman (1840-1913) to John D. Rockefeller Jr (1874-1960).

An outgrowth of her doctoral research at the Sorbonne in Paris, the book is the first one based on the Duveen firm’s own business records, housed at the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles. Vignon documents the company’s ambitions, business practices and ethics, in doing so illuminating the extensive network of dealers, decorators, fabricators and restorers with whom the Duveens worked. She observes, “Most of these documents were intended to be seen only by members of the firm, who were bound by the need for professional confidentiality, but here everything is discussed openly: secret negotiations, the prices for artworks, issues regarding the condition of objects, even misrepresentations meant to encourage clients to purchase a given work.”

Vignon charts the rise of the antiques trade in the late Nineteenth Century. Once a hawker of bric-a-brac, the antiques dealer became “a man of the world with impeccable manners… one who receives his visitors in large reception rooms soberly furnished with a few pieces in the best taste,” to quote French art critic Henri Clouzot, writing in 1923. Few individuals exemplified the new breed of merchant better than Joel, Henry and Joseph Duveen.

Brilliant marketing and an ability to capitalize on trends ensured the success of both Edith Halpert and the Duveens. But while Halpert’s approach was rooted in social idealism, the Duveens were pragmatists. The emerging portrait of the Duveens, Vignon says, “is one of art dealers willing to do anything necessary, legal or otherwise, to obtain success. In addition to manipulating their clientele, as well as the press, they circumvented the law by deceiving American customs officials, which led to one of the greatest fraud and smuggling scandals of the Twentieth Century.”

Vignon writes that, while the Duveens inevitably sold fakes, “it has not been established that they did so knowingly or that they had anything to do with their fabrication.” They worked closely with experts, made every effort to document what they sold and, if the authenticity of an object was questioned, generally took back a piece to avoid scandal.

The scholar describes the tendency of legitimate dealers of the day to disclose some, but perhaps not all, that was known about a work’s condition. Though commonplace, copying pieces to fill out sets created a gray area for dealers, as did the practice of creating two pieces of furniture from a single old piece. In one fascinating passage, Vignon describes a “suite of furniture, a Carlhian-Duveen pastiche combining old tapestries and modern wooden frames, that Duveen sold in 1919 to John D. Rockefeller Jr for the extravagant sum of $650,000. Rockefeller, who assumed he was buying antique furniture, donated the suite to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1935. At the time, no one doubted its authenticity – neither the museum’s furniture curator nor Mitchell Samuels, director of French & Company and a highly regarded specialist in tapestry and antique furniture, who had examined the dismantled components when he cleaned the tapestry covers in the 1920s.” Overall, Vignon concludes, “Duveen did what his colleagues did; he indicated some restorations but let the rest pass unremarked. He allowed a general impression of honesty to mask procedures that were less than honest.”

The Duveens created a durable business model. They bid up prices at auction and bought en bloc to protect their investments. They manipulated the press and the courts to their advantage. They understood the value of staging and the importance of a prestigious address. They provided interior design services as a way of selling merchandise. They marshalled a network of tradesmen and experts in the United States and Europe, and established trust with museums and collectors by working with acknowledged authorities. Charming and charismatic, they moved in the highest social circles. Their ultimate genius was in recognizing and exploiting the potential of the emerging American market.

Part two of Duveen Brothers examines the trade in Chinese porcelains, Eighteenth Century French furniture and objects, and medieval and Renaissance furniture and objects from the vantage point of the Duveens. The Duveen style, most pronounced between 1910 and 1940, lingered well into the late Twentieth Century and, Vignon says, can even be detected in the Charles and Jayne Wrightsman Galleries at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, endowed by the couple in 1983 and reinstalled in 2006-07.

The curator forgives the Duveens their “machinations,” writing, “their influence was enormous. They not only transformed the international art market but also contributed to changes in American artistic and cultural life.” Their legacy endures through the thousands of magnificent objects that passed through their hands and now reside in the world’s leading museums.

Duveen Brothers and the Market for Decorative Arts, 1880-1940 by Charlotte Vignon is published by D Giles Limited, London, in association with the Frick Collection in New York City. It sells for $59.95 hardcover. For more information, go to www.frick.org or call 212-547-6848.

“Edith Halpert and the Rise of American Art” is on view through February 9. An accompanying catalog of the same name is published by the Jewish Museum and Yale University Press. Hardcover copies are available at the Jewish Museum’s Cooper Shop for $50. The Jewish Museum is at 1109 Fifth Avenue at 92nd Street. For more information, go to www.thejewishmuseum.org or call 212-423-3200.