“Madonna of the Magnificat” after Sandro Botticelli (1444/45-1510), Florence, Italy, circa 1490, oil on panel. The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased by Pierpont Morgan, 1911; AZ014.

By James D. Balestrieri

NEW YORK CITY — I had occasion to work on a major exhibition of Edward Curtis’s photographs from his life’s work, The North American Indian, a few years ago and one of the things I learned quite quickly was that if Curtis hadn’t made it past Belle da Costa Greene, J.P. Morgan’s librarian, archivist and first director of the Morgan Library, the financier might never have heard of Curtis, much less funded the Seattle “Shadow-Catcher’s” obsessive dream to photograph and describe all of the major Indigenous peoples of the United States and Canada in what would ultimately become an invaluable series of beautiful volumes of images and ethnographic text.

Renowned medievalist, fierce collector, innovative librarian and scholar, staunch advocate of modernism, activist, socialite, celebrated beauty: “Belle da Costa Greene: A Librarian’s Legacy,” the new exhibition on view at The Morgan Library and Museum, reveals Morgan’s cultural gatekeeper as a fascinating and utterly unique figure, a many-faceted woman who insisted on forging and reforging her own identity — a high-wire act at a time when “one drop of blood,” as the Supreme Court’s Plessy versus Ferguson decision decreed, determined race, when Jim Crow was in full force, when “separate but equal” was a dominant fiction of the day.

A look at the objects on the pages of this essay shows the wide range, beauty and rarity of the objects she would acquire on behalf of the Morgan Library.

Greene’s own story, however, continues to intrigue.

Portrait of Belle da Costa Greene by Clarence H. White (1871–1925), 1911, platinum print, Biblioteca Berenson, I Tatti, The Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies.

She was born Belle Marion Greener in 1879 into a prominent Black family in Washington, DC. Her father was the first Black Harvard graduate. When her parents separated in 1894, her mother changed the family name to Greene. Belle and her siblings were light-skinned and the family made a decision to pass as white. By 1903, Belle and her brother had added “da Costa” as a middle name and had begun to tell people their ancestry was Portuguese, thus accounting for their darker complexions.

Books, especially rare books and manuscripts, coursed through Greene’s blood from an early age, and she showed an aptitude for languages, as described in the exhibition’s catalog: Her father collected “rare books and documents related to African American history,” had “knowledge of classical European languages” and had worked in the University of South Carolina’s library. By the age of 13, Greene recalled, she had wanted to become a librarian. Despite all the roles she played, “librarian” was what she called herself whenever she was asked.

As for education, Greene studied at the Northfield Seminary for Young Ladies, Amherst College’s five-week Summer School of Library Economy, worked at the Teacher’s College in New York, then, probably, at the New York Public Library before finishing her training in the Princeton University Library, a place that would have rejected her out of hand had they learned of the truth of her racial background. At these various institutions, Greene improved her French and Latin, absorbed the latest in library science and began to explore “paleography, textual criticism, historical bibliography,” and other languages. At Princeton, she met Junius Spencer Morgan, an associate librarian, the nephew of J.P. Morgan and son of Jack Morgan, who would assume responsibility for the library after J.P.’s passing. Junius introduced Greene to his uncle and Greene was on her way. It would not be long before Morgan’s rather haphazard assortment of exceptional objects would become her dream, a dream of transforming the collection into a library, one that would ultimately be “pre-eminent.” It would not be long before Morgan would rarely purchase a book, manuscript, or work of art without Greene’s approval, while Greene would often acquire objects without consulting with J.P. or, later, Jack.

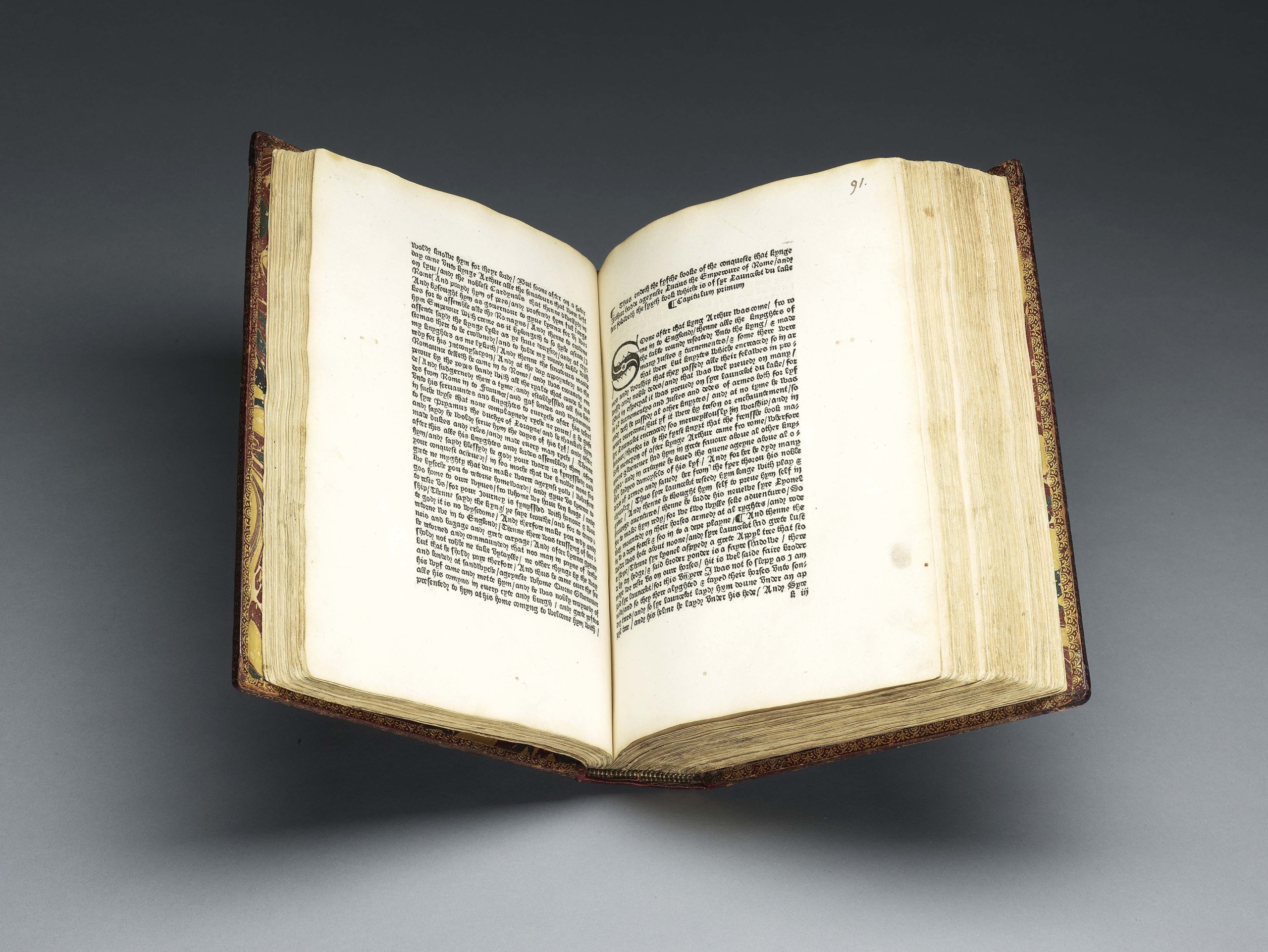

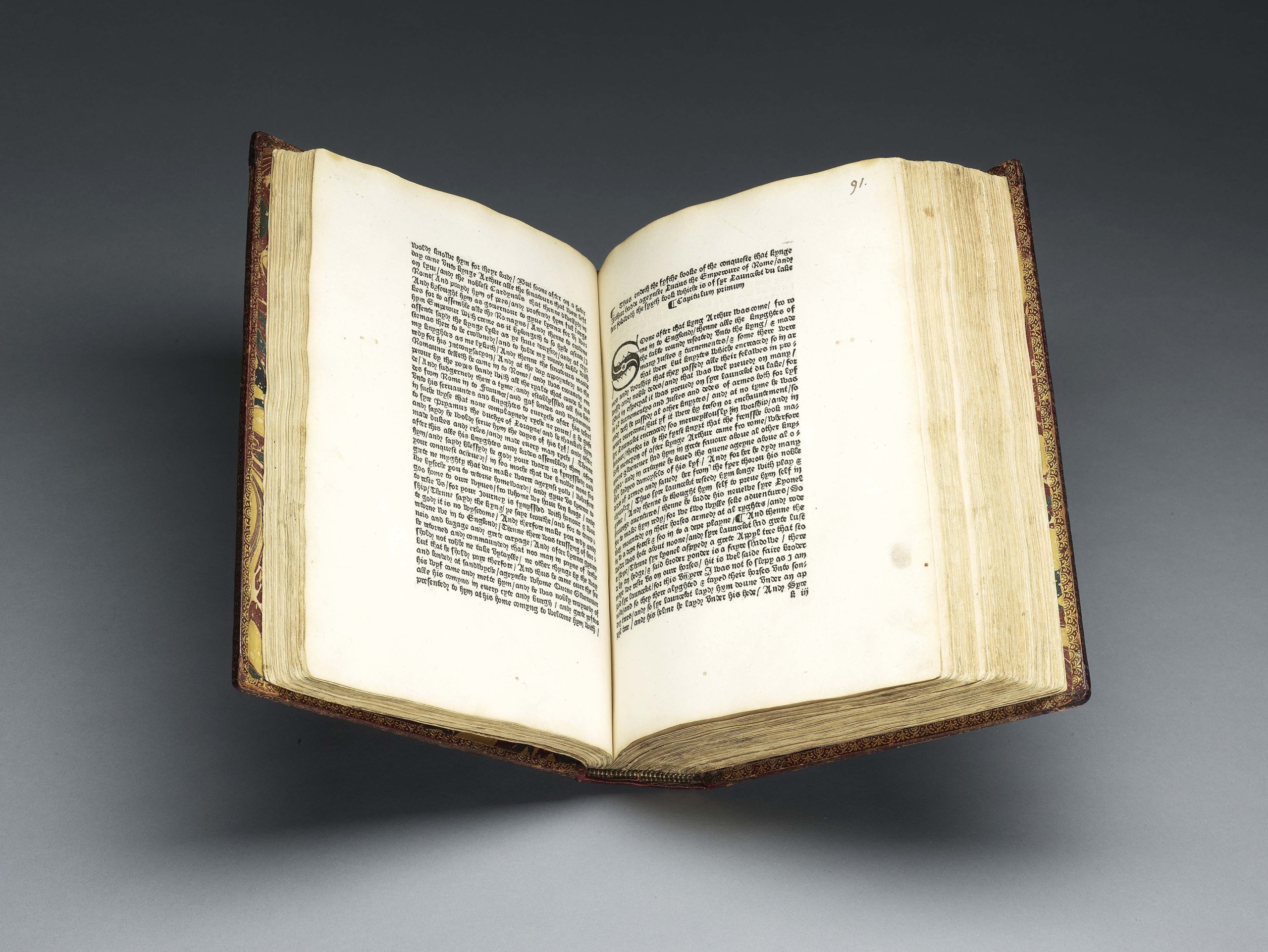

Sir Thomas Malory (act. Fifteenth Century), Thus endeth thys noble and joyous book entytled Le morte d’Arthur Westmestre: [William Caxton], the last day of Juyl the yere [sic] of our lord /M/CCCC/lxxxv [July 31, 1485]. The Morgan Library & Museum, purchased by J. Pierpont Morgan, 1911; PML 17560.

Some of Greene’s finest acquisitions are the gorgeous Eleventh Century Gospels of Judith of Flanders, the unmatched 1485 Caxton printing of Mallory’s Le morte d’Arthur and the fantastic 1490 Botticelli roundel, “Madonna of the Magnificat,” with its fish-eye illusion in which the figures seem to project from the frame, defying any distance between subject and viewer. In others, such as the autograph manuscripts for Balzac’s Eugénie Grandet and Dickens’s Our Mutual Friend, you see Greene’s preference, mirroring ours, for the early drafts of masterpieces, the ones that expose the thought processes of the authors, showing their corrections and hesitations, their scrawls, scribbles, doodles and crossings-out. In this, she was ahead of her time, when fair copies and first editions would have been seen as more important.

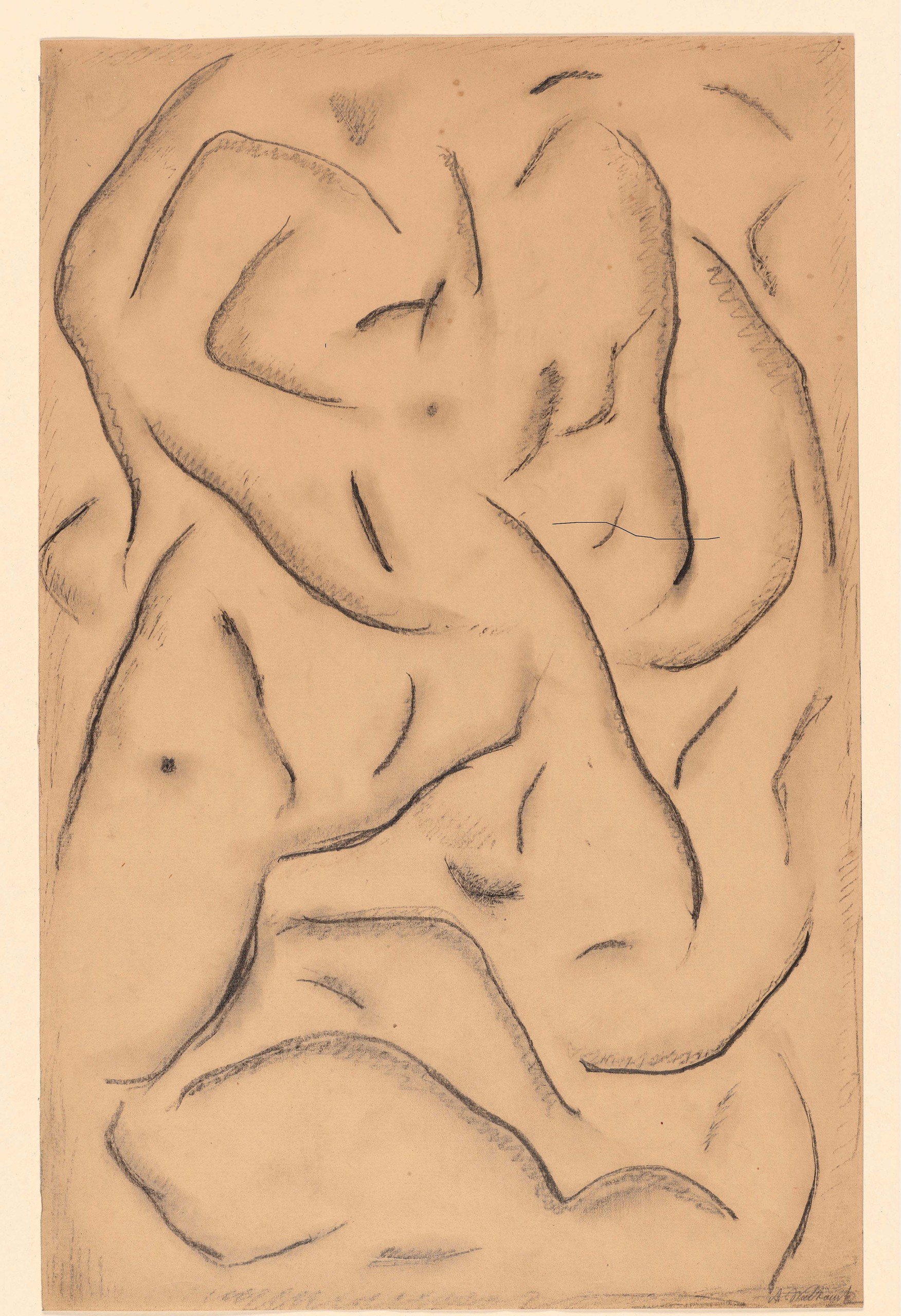

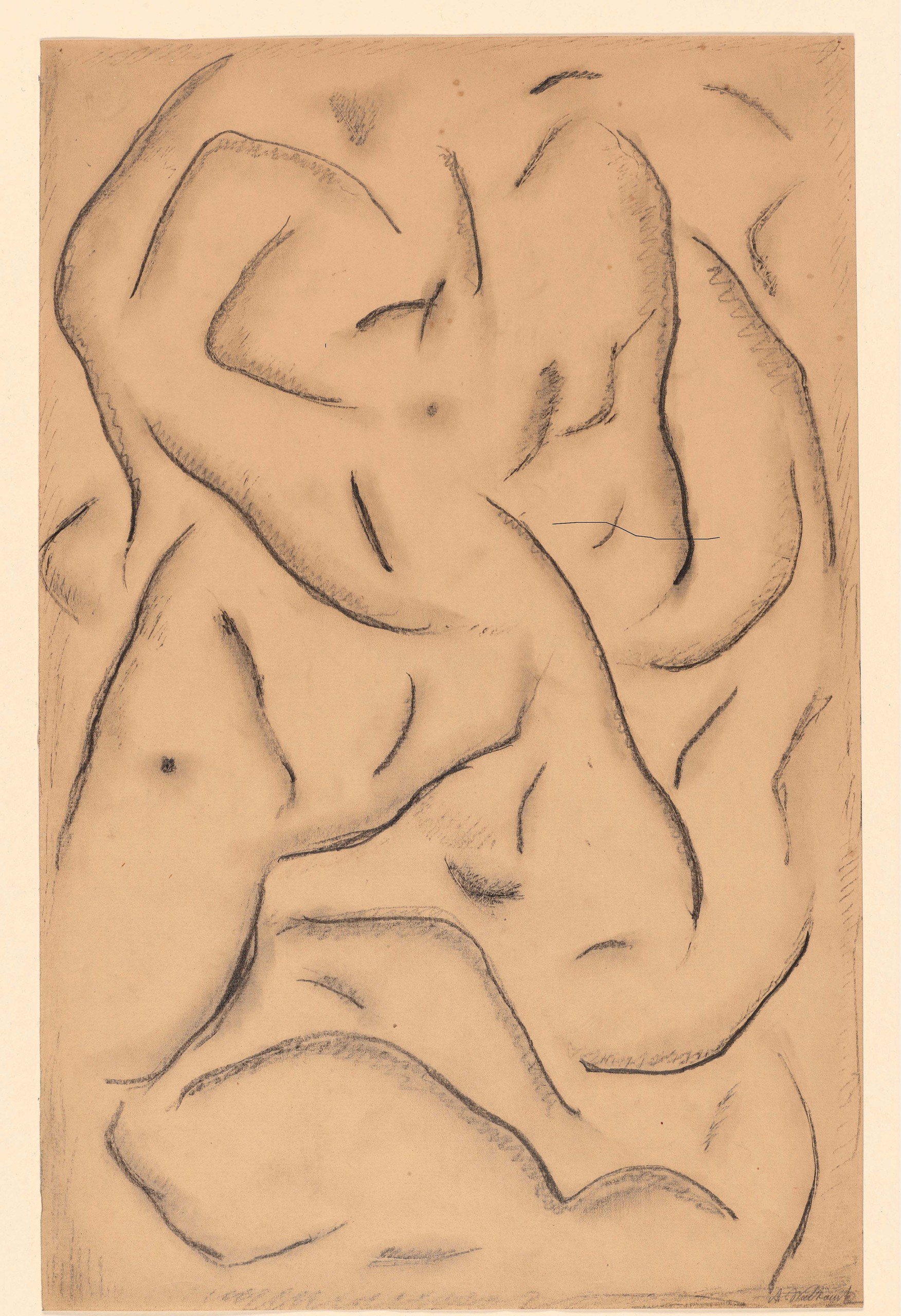

Greene’s own collection was eclectic and, it would seem, highly personal. For example, despite her medievalist bent, as evidenced in the fine Albrecht Dürer engraving “Melencolia I,” she became close friends with Alfred Stieglitz and the circle of modernists who frequented his gallery, 291. As a result, modernist Abraham Walkowitz gave her two drawings, one of which, titled “Human Abstract” and done circa 1913, the year of the famous Armory Show, may well be what the show’s catalog describes as an “abstract depiction of [dancer Isadora Duncan’s] movement.” Duncan’s modern dance, fashioned after classical ideas, attracted Greene greatly, as did the entire modernist project (apart from Gertrude Stein, whom she seems to have disliked). In “Human Abstract,” the body is a swirl of parts in motion, coming apart or perhaps on verge of coming together in a new way. One can superimpose Greene’s ever-shifting identity onto the work; one wonders if this ‘literal metaphor’ might not be what attracted her to it or, perhaps, what made him offer it to her as a gift.

“Human Abstract” by Abraham Walkowitz (1880-1965), circa 1913, graphite. The Morgan Library & Museum, gift of the Estate of Belle da Costa Greene, 1950; 1950.22.

Greene had a modern take on celebrity. When photographers and artists lined up to make portraits of her, she carefully orchestrated her image. She was stylish and radiated confidence. As Deborah Willis writes in her catalogue essay, “Her photographs did much more than record her presence in Morgan’s life; they claimed her notability, her sexuality and blurred the lines of her racial passing. Greene’s portraits typified her ideals, and she knew how to use portraiture to establish an identity outside of the respectability lens of the New Negro woman.” Julia S. Charles-Linen’s essay deepens our understanding of Greene’s success at “passing” in her own essay, stating, “Greene disrupts the notion of legal race as always legible on the body, by highlighting the ways in which Greene’s strategic racial performances, along with her then-burgeoning reputation in acquiring rare artifacts, made room for her ascension into the often covert world of art and polite society in New York….” In her 1910 portrait — a profile, as are many of the extant images of her, showing, perhaps, only one side, one facet of her identity while leaving the other in mystery — Greene is classical, Grecian, almost numismatic in her beautiful regality and suggestion of great value and worth. Just a year later, the 1911 portrait shows her white-gloved hands holding her knee while white lace elongates her throat and her furred and feathered hat, a Greene trademark, is pushed back off her forehead. Her cocked head, half-smile and eye on some distant prize hints at a plan, a secret plan, a plan that excludes us, at least for now.

Photo of Belle da Costa Greene by Ernest Walter Histed (1862-1947), 1910, gelatin silver print. The Morgan Library & Museum; ARC 2702.

The mystery Greene cultivated captivated. Not only New York but, as Charles-Linen writes, the “often covert world of art…” In a way, as the two photographs in this essay suggest, Greene’s ever-shifting identity — her bold bargaining and bidding among dealers and collectors, her meticulous cataloguing, her unerring eye for quality, whether in in dressing herself, choosing her friends, or in assessing cultural objects — made her that rarest of objects, an object that refuses to be objectified, a living “Grecian urn” that everyone will reach out for but no one will ever quite reach. Even in her private life, she remained elusive, never marrying, though she had a long and largely long-distance relationship with Renaissance art scholar Bernard Berenson, the most important art critic, advisor and tastemaker of the era. Born Jewish, Berenson converted to Episcopalianism; his “passing” perhaps added to his sympathy for and with Greene, who revealed her origins to him. Overt racism eventually made its way into Greene’s life in devastating fashion when her nephew Bobbie — whom she had made her ward, taken in and educated — committed suicide when his fiancée learned the truth of his ancestry and rejected him. It’s impossible to know the exact why of it, but before her death in 1950, Greene burned most of her personal papers, taking her many secrets to the grave and preserving something of the mystery that made her who she was during her life.

In the end, “Belle da Costa Greene: A Librarian’s Legacy” goes well beyond the fact of the Morgan Library, her key role in its development and its ongoing place among the world’s great cultural institutions. Greene herself left a legacy — she herself is that legacy — one that goes beyond her many accomplishments in the arts and beyond her successful “passing.” Her legacy is her daring at a time when it was perilous to dare, when her daring, had it been exposed, would have been seen as shameful and would have resulted in her dismissal — if not jail or death — a time when the real shame was the nation’s shame.

“Belle da Costa Greene: A Librarian’s Legacy” is on view at the Morgan Library and Museum from October 25 through May 4.

The Morgan Library & Museum is at 225 Madison Avenue. For information, 212-685-0008 or www.themorgan.org.