Richmond Barthé’s (American, 1901-1989) “Feral Benga” bronze sculpture surpassed all expectations when it sold for $629,000 on a $60,000 high estimate. It sold to a private collector. The work depicts Senegalese dancer François “Féral” Benga, who performed at the Folies Bergére and would become a subject of other Harlem Renaissance artists. The 19-inch-high sculpture was numbered 1 from an edition of 10 recast in 1986 under Barthé’s supervision. There are only two known from the original 1930s casting.

Review by Greg Smith, Photos Courtesy Swann Galleries

NEW YORK CITY – Swann Galleries’ 187-lot African American Art sale on June 4 went 88 percent sold against the backdrop of Black Lives Matter protests that took to the streets nationwide. Whether the genre’s market is relative to the broader African American experience in the United States is one question, but undeniable is the relationship between that experience and the artwork, its artists and subjects.

It was the second sale the department has organized this calendar year, the first being the Johnson Publishing auction in January, which offered works from the archives of Ebony and Jet magazines. That 87-lot sale went white glove. The June 4 auction did $3.5 million, rising just above the estimate of $2.3/3.4 million.

Buoyed by the contemporary market for African American artists, the secondary market is seeing a steep rise in those individuals from the postwar and modern era. Department director Nigel Freeman said that 2018 and 2019 were record years for his sales and it shows no signs of slowing. Freeman founded the department at Swann Galleries in 2006. It has become a leader in African American art auctions, pushing artist records higher every year and at times introducing artists to the secondary market.

Freeman put this sale together in early spring as the auction was originally scheduled for April. Due to restrictions in New York City on account of the pandemic, that sale date was pushed forward to June.

“There was no exhibition and no one was able to view the property before the sale,” Freeman said. “So essentially it was just sold according to the catalog – our descriptions, our condition reports and images. Building on the history we have in the field and our reputation leading it, people were comfortable with how we described the lots, though we would have loved to have shown our clients the work. It was great to have the kind of success we had. We saw many new clients in addition to our regular clients coming back and continuing to follow our sales.”

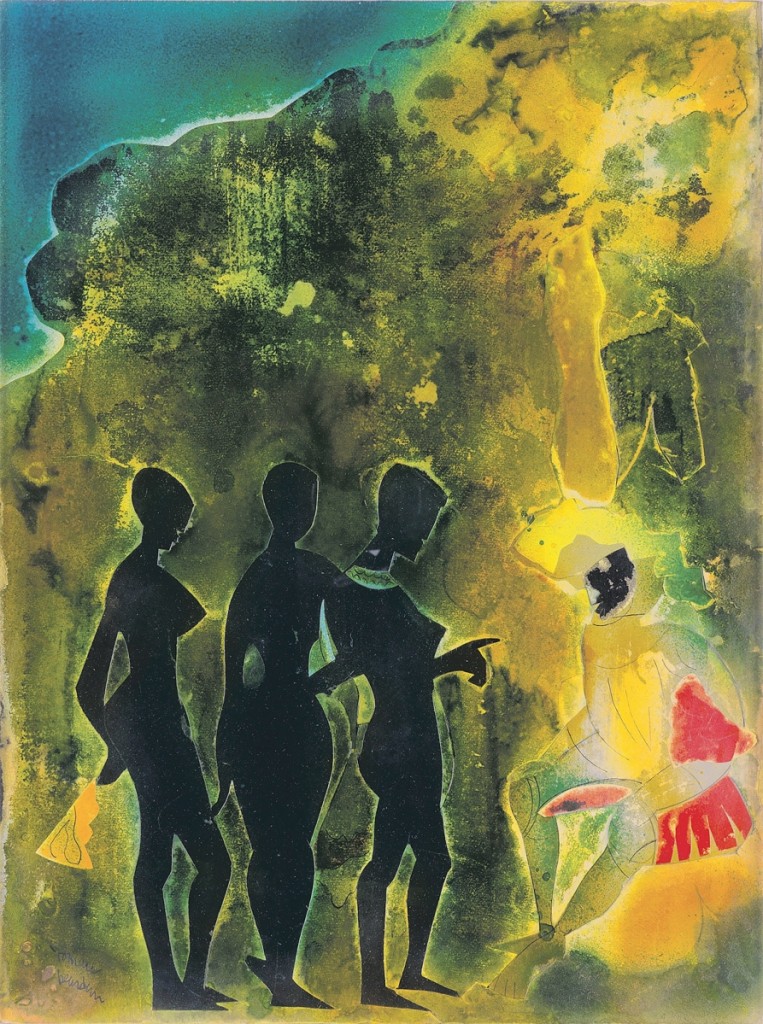

The second highest auction result for any work by John Biggers (American, 1924-2001) sold at $269,000 for “Women, Ghana,” a 32-by-40-inch oil on Masonite board. The work was produced from a series of drawings that Biggers executed on a UNESCO fellowship in 1957. The series has produced his most valuable works at auction thus far.

The auction house could not have foreseen the nationwide protests that would propel African American issues and systemic racism to the forefront of the national conversation, but Freeman said that in some cases, the material on offer spoke to the same concerns.

“As a department that represents African American fine artists, we’re very much attuned with the concerns of African Americans who continue to face these issues,” he said.

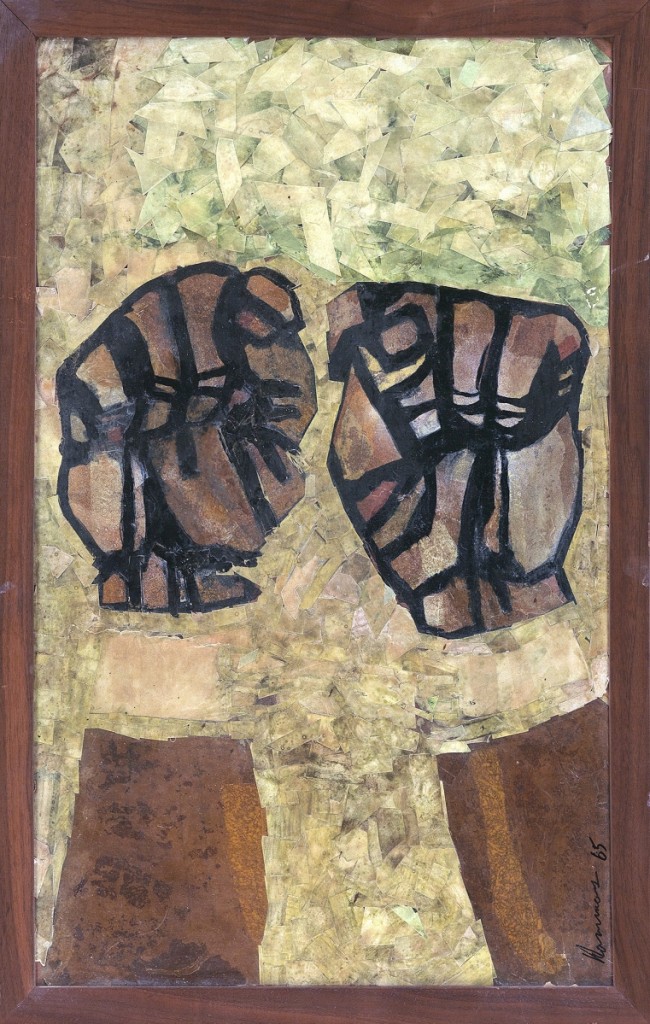

Among them was an untitled paper collage and tempera on Masonite board work by David Hammons (American, b 1943), which depicted two shackled fists raised into the air. It measured 24 by 15 inches and sold for $137,000. Freeman says he believes it is the earliest work by Hammons ever sold at auction, given to his college roommate on the occasion of his wedding in 1966. It remained in that collection ever since.

“It predates his first main period that people know, his body prints, and we’ve had some of those,” Freeman said. “They date from the late 60s, so this is three or four years before that when he was just beginning his artistic journey.”

Hammons would use the image of a raised fist, a civil rights icon, in later work as well.

Another Hammons work that related to the moment, and indeed a long history of oppression and police brutality, was “The Man Nobody Killed,” a stenciled paint and collage printed on cardboard depicting Michael Stewart, an artist who died in custody of the New York City Transit Police in 1983. All officers were acquitted at trial by an all-white grand jury, though the family won a $1.7 million civil suit years later. Dr Elliot M. Gross, the chief medical examiner who orchestrated a cover up as he released three different conclusions on Stewart’s death, was later fired, though he faced no further repercussions. The prosecution of that case more than 30 years ago hoped to establish a law that required police officers to have an affirmative duty to protect prisoners in their custody from abuse. Federal and state regulations continue to fail to require this of police. Hammons’ work on Stewart was from an edition of 200, though each features a unique variation. It was originally featured in “Cobalt Myth Mechanics,” 1986/1987, Eye Magazine, #14. It sold for $22,500. The Michael Stewart case was explored in the 2019 exhibition at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, “Basquiat’s ‘Defacement:’ the Untold Story.”

David Hammons’ (American, b 1943) untitled work featuring two fists shackled and raised into the air sold for $137,000. Nigel Freeman believes it is the earliest work from the artist to ever come to auction, produced in 1966 as a wedding gift for the artist’s college roommate. It remained in that collection ever since. The subject is the icon of the Civil Rights Movement and would be a subject that Hammons returned to in later work.

The sale found strength in a number of places, among them its top lot, “Feral Benga” by Richmond Barthé (American, 1901-1989), a bronze sculpture that sold for $629,000 on a $60,000 high estimate. Freeman said it was a bidding war between two determined collectors. It swiftly surpassed Barthe’s previous auction record, which was $87,500 for a bronze in a 2017 sale at Swann Galleries.

Barthé was no doubt impressed by the Senegalese dancer François “Féral” Benga, who he saw perform at the Folies Bergére on his first visit to Paris just months before modeling the work in 1935. Benga would become a subject of other Harlem Renaissance artists.

“It’s an iconic work, his best-known work, and a work that really established him as one of the preeminent sculptors of the early Twentieth Century,” Freeman said.

The 19-inch-high bronze was from an edition of ten recast in 1986 under supervision of the artist. Only two are known from the original 1930s casting. It was originally exhibited in the 1937 Dance International exhibition at Rockefeller Center, New York City.

Work from John Biggers (American, 1924-2001) produced strong results, including a $269,000 sale of “Women, Ghana,” a 32-by-40-inch oil on Masonite board, circa 1960. In 1957, Biggers received a UNESCO fellowship to study and record traditional African culture. He visited Ghana, Togo, the Republic of Benin and Nigeria with his wife over a period of six months. Along the way, he recorded what he saw in drawings in preparation of a larger body of work that he would produce upon his return. Biggers’ most valuable works are from this series, including “Kumasi Market,” a work that established the artist auction record at $389,000 in Swann Galleries’ 2015 sale of the private collection of Dr Maya Angelou.

“Aphrodite” by Romare Bearden (American, 1911-1988) sold for $106,250 on a $60,000 high estimate. Collage and acrylic, 1973, 24 by 18 inches. It had been exhibited at the Mint Museum in “Romare Bearden: 1970-1980,” an exhibition that traveled to the Mississippi Museum of Art, the Baltimore Museum of Art, the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts and the Brooklyn Museum.

Five works from Ernie Barnes (American, 1938-2009) came from a California collection with three of them selling higher than the artist’s previous auction record of $47,500, set by Swann Galleries in 2017. All of the works had been acquired directly from the artist. At the top was “New Shoes,” an 18-by-24-inch acrylic on cotton canvas, circa 1970, that sold for $68,750. It was a feel good work, featuring a man strutting down the sidewalk in full stride giving off a sense of style and pride. “In The Beginning,” an 18-by-24-inch acrylic on cotton canvas, featured a young man shooting his basketball on a makeshift hoop in a field with a farmhouse in the distance. It sold for $57,500. Freeman wrote that it was one of Barnes’ most iconic images and was reproduced in a 750-print lithograph edition. It was framed in wood from a weathered picket fence, which Barnes said he did in honor of his father. The last record breaker was “Pool Hustlers,” a 44½-by-30-inch acrylic on cotton canvas, which sold for $55,000.

An introduction to the secondary market was made for photographer Latoya Ruby Frazier (American, b 1982), who was represented by two works in the sale. Both silver prints would pass the $6,000 high estimate on each, with “Gramps on His Bed” setting the bar at $10,625 and “Grandma Ruby’s Porcelain Dolls” taking $9,375.

Works from masters Romare Bearden, Elizabeth Catlett, Sam Gilliam and Norman Lewis all traded hands as well.

Delaying the sale proved beneficial for Freeman as he was able to take the time and speak to clients throughout the pandemic shutdown. The catalog had been printed in late March and was in the hands of his bidders as they sat home and counted down to June 4.

Swann Galleries’ next African American Art sale is scheduled for November. For more information, 212-254-4710 or www.swanngalleries.com.