By Jessica Skwire Routhier

SHELBURNE, VT. – It’s the most wonderful time of the year – or is it? For nearly four full months, from Halloween to Valentine’s Day, American culture is saturated in sweets. While we delight in and fantasize about the barrage of goodies – visions of sugarplums and all that – we also deal, individually and collectively, with its repercussions. For every Sugar Daddy we chew, every ring pop we suckle, every intoxicating sugar rush, we must also grapple with the downside (the underbelly, if you will) of indulgence: the lost filling, the ruined palate, the emotional crash and, of course, the expanded waistline.

Throughout this year’s season of sweets, Vermont’s Shelburne Museum offers an irresistible overview of both the draw and the drawbacks of sugary treats, through the lens of contemporary art. “Sweet Tooth: The Art of Dessert” is on view through February 18.

It is the draw, the appeal, that is most apparent at first. The show is a visual confection, beginning with a curlicued title panel – sprinkled with what looks like screen-printed Mike and Ikes – that sends visitors off with a cheery “Bon Appétit.” Just beyond is a scene that alluringly melds childhood fantasies, from the board game Candyland to Hansel and Gretel to Willy Wonka. Donuts by Peter Anton pop off the walls, high-heeled shoes by Chris Campbell appear to be made out of cake and waffle cones and king-sized ring pops and lollies by the aptly named Desire Obtain Cherish seem amply equipped to satisfy even the most monstrous sugar craving.

“We really wanted people to relate to the show on their own terms,” says Shelburne curator Kory Rogers, “so when you walk in, if you just want to see beautiful works of art or delicious treats, that’s one way of looking at it.” It is certainly not the only way, though, and that is made explicit in the texts that accompany the works on view. A central theme here is desire – desire that can be indulged, yes, but also repressed or thwarted – and the capacity of desserts to both stimulate and slake that desire.

“I talk about dessert as this femme fatale of meals,” says Rogers’s co-curator, Carolyn Bauer. “It’s seductive, but at the end we’re kind of paying the price for indulging.” In every fairy tale, it bears noting, magical candylands are arenas for despair as well as delight.

“I talk about dessert as this femme fatale of meals,” says Rogers’s co-curator, Carolyn Bauer. “It’s seductive, but at the end we’re kind of paying the price for indulging.” In every fairy tale, it bears noting, magical candylands are arenas for despair as well as delight.

Bauer also observes that, despite all visual evidence, the things you see in Shelburne’s galleries are not actually designed to satiate gustatory desires. The point is so obvious that the bewitched visitor – rather like Scrooge McDuck with dollar signs in his eyes, though here it is the donuts occluding one’s vision and judgment – is surprised not to have taken it in earlier.

These are not actually desserts you are seeing; they are works of art. That means that not only can you not eat them (and you would not want to; the ring pops are made from plastic resin); you also cannot touch them. They are much too big to eat, anyway. You cannot imagine lifting one of those lollipops, much less putting it in your mouth. Further, as Bauer points out, these are permanent objects, not ephemeral ones, like actual candies or desserts – so they are meant to endure, in their frustratingly indigestible form, outlasting and repelling any idea we might have of consuming them in any literal way.

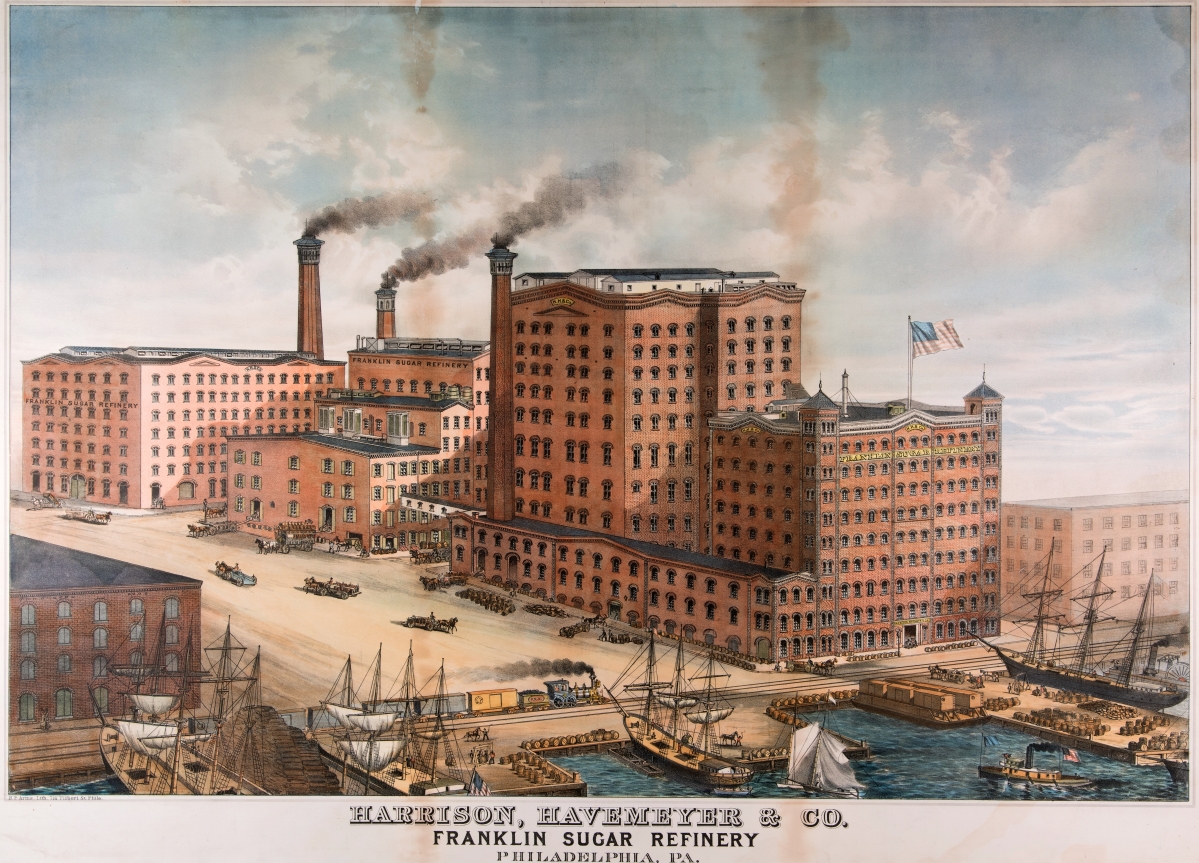

Such complex psychological themes might seem to be outside the usual tastes of Shelburne Museum’s audience. While the museum has increasingly presented important exhibitions of Twentieth and Twenty-First Century art in recent years, in many circles it remains best known for the palatable genres of French Impressionism and American folk art. In fact, sugar and its sins are baked into the history of the museum and its collections – in more ways than one. The museum’s founder, Electra Havemeyer Webb, was the daughter of H.O. Havemeyer, whom Rogers describes as the “sugar king of America” in his day. “

“Sugar Teeth — Fixing” by Marion Luttenberger, 2014. Pigment print, 20 by 26 inches. Courtesy Marion Luttenberger.

During the latter part of the Nineteenth Century into the early part of the Twentieth Century, he started the Sugar Trust,” Rogers notes. “They controlled 17 out of 23 working sugar refineries” that serviced American consumers, a monopoly that at one time controlled as much as 98 percent of all sugar in the United States.

By including a group of historical objects in the introductory section of the show, the curators have, in Rogers’s words, sought to “acknowledge the fact that this museum was founded with the money of a robber baron.” Among these are a print of the Havemeyer refinery in Philadelphia and selections from Webb’s personal collection of Staffordshire sugar bowls. The latter are inventive, ornate little things with round bellies and pagoda tops, subtle reminders that the proliferation of sugar in Western culture had everything to do with trade and imperialism. (The relationship between sugar and the slave trade was, famously, a major concept behind artist Kara Walker’s influential “Sugar Baby” installation in Brooklyn in 2014.)

Only a few of the objects in “Sweet Tooth” deal overtly with political themes, but there are two that are worth mentioning in this context. Both are featured in “Temptation: The Dessert Counter,” an exhibition-within-the-exhibition that highlights – in an actual dessert case – small-scale works by Vermont artists who responded to a call to create works especially for this show. Mary Zompetti’s “Worker Bee Sugar Bowl,” Bauer says, is a “direct conversation with the sugar industry and its harsh impact on the environment, and specifically with honeybees,” which are dying off in large numbers due to pesticides and loss of food sources and habitat. The artist’s accompanying statement explains that the dismembered bees (real, but not killed for the purposes this project) encased in the resin bowl also represent the plight of workers in the agro-industrial complex.

The second work, Kat Clear’s “‘Let Them Eat Cake,’ said Ivanka,” is inspired by the artist’s memory of her mother admonishing her not to talk politics at a party. Three pewter and plaster mini-cupcakes, titled thusly and preciously arranged on a dessert plate, challenge viewers to consider what they sacrifice when they regard sweetness as a viable alternative to speech. The piece engages with national conversations about politeness and complicity.

“Blowpop Jackhammer” by Christopher Boffoli, 2012. C-print on metallic paper, 24 by 36 inches. Courtesy Christopher Boffoli / Big Appetites.

As a rule, the exhibition’s artists deal less with such broad issues than with the more individual and psychological aftereffects of sugary indulgence. Rogers points to “Eye Candy,” a suite of candy emojis created by Elizabeth Berdann: “The facial expressions are created out of these artistically arranged candy tableaux,” he explains. “Licorice whips become frowny faces, watermelon slices become downcast eyes… Really what she’s talking about here is her own relationship to overindulgence… You have that euphoric moment where you get that sugar high, but for those of us who can’t monitor our intake we do suffer from a range of sad emotions that go from self-loathing to depression. I think hers more than anyone else’s in the show is about a real direct relationship between emotions and sugar.”

The ways in which the enjoyment of sugar seems almost invariably to devolve into emotional and physical discomfort, even decay, is also a theme in staged photos by Austrian artist Marion Luttenberger that Bauer describes as “visual puns.” In each photo, Luttenberger creates a montage of teeth that are made of sugar. In “Sugar Teeth – Fixing,” sugar cubes are arranged in the form of a wide-open, toothy maw, as if being presented for a dentist. A set of sugar tongs grips one cube in the place of a lower canine, prepared for extraction.

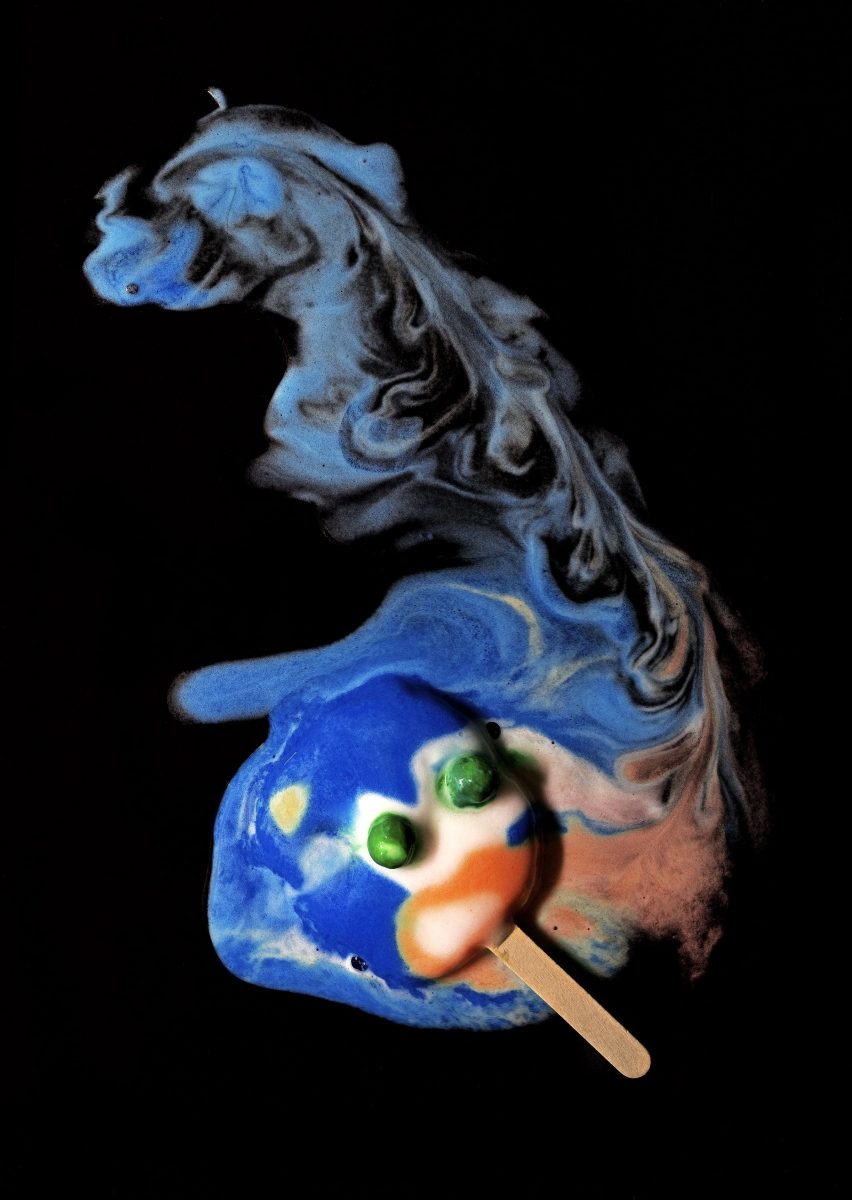

For all that the sculptural works in the show – which also include the enormous crumpled candy-wrapper sculptures of Paul Rousso and ceramics by Dirk Staschke – are attention-getters, they do not overshadow the flat works. The photographs include not only Luttenberger’s teeth but also Christopher Boffoli’s whimsical images of tiny industrial workers laboring over candy landscapes, and Michael Massaia’s discomforting color prints that somehow simultaneously allude to ice-cream-truck novelties, MRIs, cartoons and Rorschach tests. The paintings are also standouts, each in its own way employing the qualities of oil paint – slickness, high polish, viscosity – to represent sweets in an intensely illusionistic way. Margaret Morrison’s “Candy Apples,” for instance, shine with invitation, their large scale, once again, making the idea of consuming the treats they describe seem as irresistible as it is impossible.

Works by Ivan Alifan and Kay Kurt also use scale and hyperrealism to play with ideas of desire. Aifan’s “Deserted” depicts a downcast male head, covered with gooey fluff and topped, William Tell-like, with a partially melted waffle-cone sundae. “There’s this somewhat ambiguous quality about it,” says Rogers. “To adult eyes his paintings look very sexually charged; to children’s eyes his work looks like victims of a food fight… you read into it what you want to read into it.” There is a similarly visceral quality to Kurt’s 9-foot-wide painting of tangled and intertwined licorice whips. It is possible, arguably, to look at this as a purely formalistic exercise – a study in red and black – but there is clearly more to it. A veteran Pop artist, Kurt has used candy as her primary subject matter for more than 50 ears, often titling her paintings in ways that force a reckoning with issues of desire, submission, ecstasy and denouement. Here, the association with Icarus – the Greek hero whose handcrafted wings melted when he flew too close to the sun – suggests a limit to the pleasures that it is wise for human beings to pursue.

The punning titles of both “L’Icarus” and “Deserted” enhance the idea of double or hidden meanings, and of the viewer’s ability to choose the way in which he or she chooses to indulge. “Sugar’s loaded,” says Bauer, and so are all of the works on view in “Sweet Tooth.”

Shelburne Museum is at 6000 Shelburne Road. For information, www.shelburnemuseum.org or 802-985-3346.

Jessica Skwire Routhier is managing editor of Panorama, the journal of the Association of Historians of American Art. She lives in South Portland, Maine.