BOSTON – The 2017 Ward Francillon Time Symposium, sponsored by the National Association of Watch and Clock Collectors (NAWCC), will be presented in the Alfond Auditorium at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts (MFA) October 26-28. The theme, never before addressed at a major conference, focuses on the appearance and significance of clocks, watches, hourglasses and sundials as depicted in an international array of important works of art.

“The Emperor Napoleon in His Study at the Tuileries” by Jacques-Louis David, 1812. National Gallery of Art.

Eighteen art historians, among them curators and scholars, will present illustrated lectures on the areas of their expertise, utilizing artwork examples featuring timepieces. Attendees will hear from experts such as Princeton University emeritus curator John Wilmerding and University of Lyon, France, emeritus professor Philippe Bordes. Also scheduled to speak are MFA curators Dennis Carr, Thomas Michie, Lawrence Berman and Emily Stoehrer. MFA emeritus curator Gerald W.R. Ward will deliver “Frozen in Time: The Museum as History’s Clock” at the concluding dinner banquet hosted at the Harvard Club of Boston.

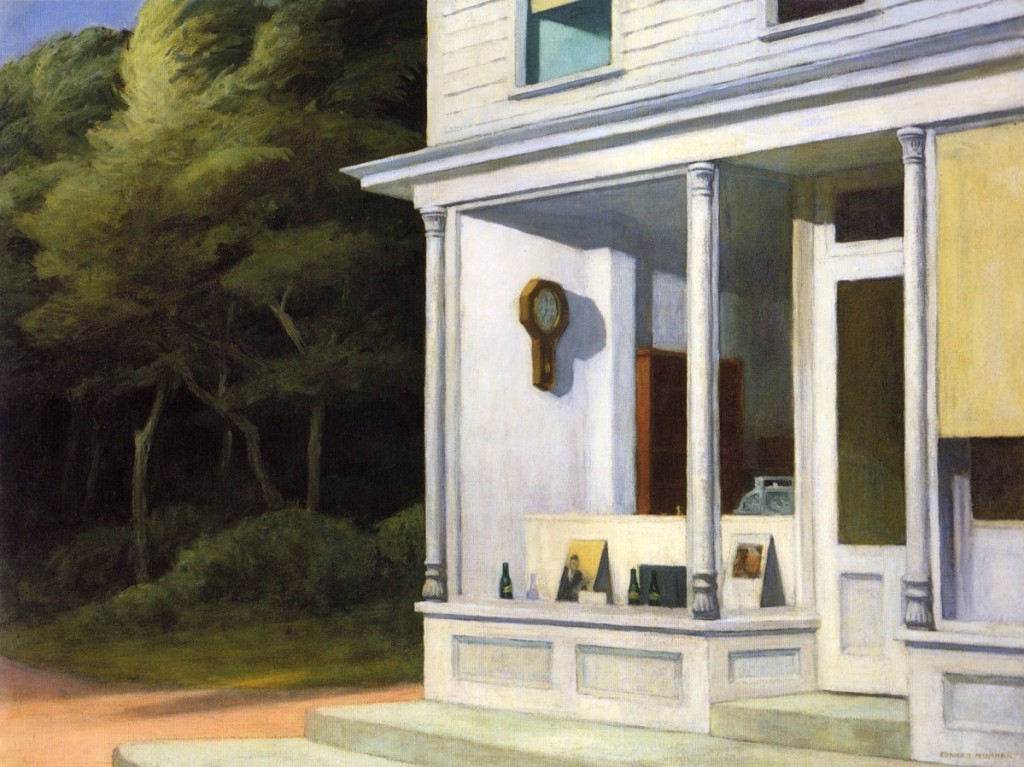

For more than 2,000 years, timekeepers have appeared in art. An ancient Roman mosaic depicting “Plato’s Academy” showed a pedestal-mounted sundial. A 1285 manuscript illuminated a water clock, several Sixteenth Century Renaissance portraits by Titian featured small gilt mechanical table clocks, American folk and genre painters included banjo and tall clocks in their domestic scenes and Marc Chagall often depicted a German wall clock from his Eastern European boyhood home. Jamie Wyeth’s 1994 view on Monhegan Island had his teenage model Orca Bates posed next to a stately antique grandfather clock still in the Wyeth household.

Unlike random photo snapshots, nothing in paintings, drawings, prints and fine art photography appeared by accident. Each artist decided what to include. In many, if not most, instances where clocks and watches are present, they had symbolic or metaphorical significance. When mechanical timepieces first appeared in the Thirteenth Century, analogies to “God the clockmaker” were common, linking a clock’s steady self-propelled action to the motion of the entire universe. During the Renaissance, timekeepers demonstrated a person’s or city’s affluence, discipline and technological sophistication.

Later artworks continued to use clocks and watches to symbolize mortality and the need for people to wisely use their time on earth. More modern depictions have emphasized the growing tyranny of timekeeping that governs all our waking hours. Sometimes the timepiece simply showed the time, but usually for a specific reason.

Bob Frishman is chairmen of the NAWCC Symposium Committee and the event’s organizer. Founder and owner of Bell-Time Clocks in Andover, Mass., Frishman is a NAWCC Fellow and a Freeman of the London-based Worshipful Company of Clockmakers. He lectures regularly on “Horology in Art” and has written more than 35 feature articles on the subject for the NAWCC magazine.

The National Association of Watch and Clock Collectors, founded in 1943 and boasting 12,000 members, is the world’s largest horological organization and sponsors an annual educational conference.

The cost of the conference, including the Harvard Club banquet, is $350 per person, or $300 for MFA members. The registration deadline is October 10.

All details are posted at www.horologyinart.com.