San Zeno Astrolabe, Italy, Verona, circa 1455, illuminated for the Abbey of San Zeno by an anonymous Lombard artist, private collection of Richard Cloward. Image courtesy of Map & Atlas Museum of La Jolla, Michael Stone, founder.

NEW YORK CITY – What time is it? The question seems simple, and with a watch on your wrist or a cellphone in your hand, the answer is easy. In the Middle Ages, however, the concept of time could be approached in many different ways, with vastly different tools. Before the appearance of the clock in the West around the year 1300, medieval ideas about time were simultaneously simple and complex. Time was both finite for routine daily activities and unending for the afterlife; the day was divided into a fixed set of hours, whereas the year was made up of two overlapping systems of annual holy feasts. Perhaps unexpectedly, many of these concepts continue to influence the way we understand time, seasons and holidays into the Twenty-First Century.

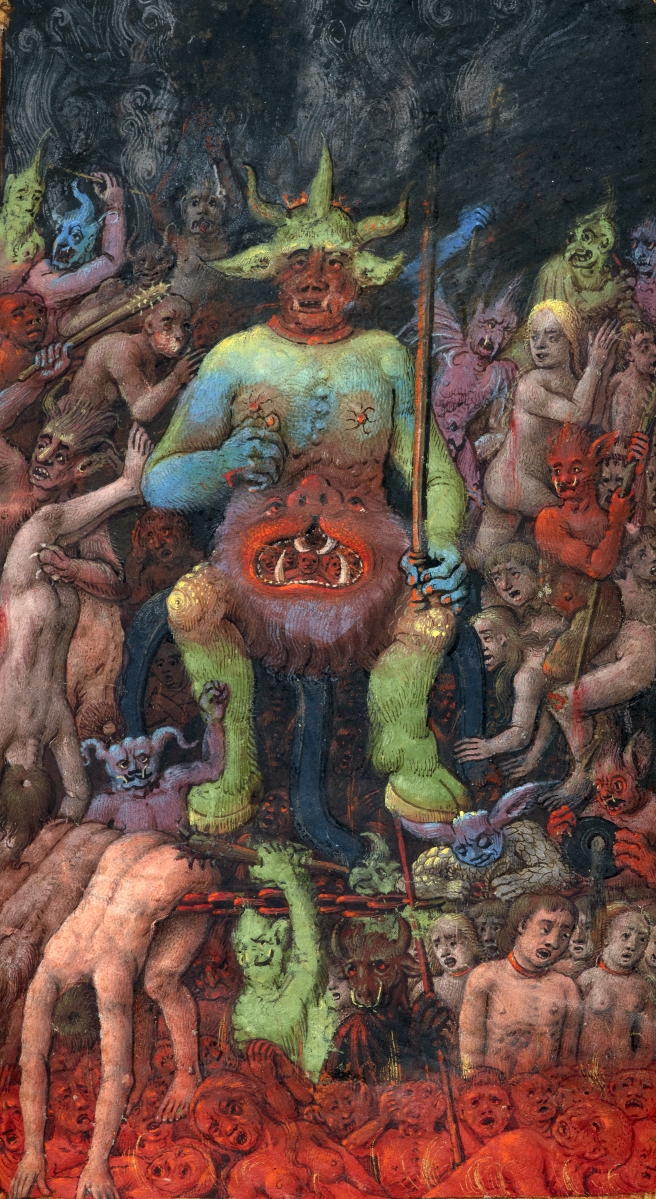

Drawing on the Morgan Library and Museum’s rich collection of illuminated manuscripts, “Now and Forever: The Art of Medieval Time” explores how people in the Middle Ages told time, conceptualized history and conceived of the afterlife. It brings together more than 55 calendars, Bibles, chronicles, histories and a 60-foot genealogical scroll. The exhibits include depictions of monthly labors, the marking of holy days and periods and fantastical illustrations of the hereafter. The exhibition continues through April 29.

“Artists of the medieval period could render the most common of daily activities with transcendent beauty, while also creating a strange, often frightening, afterlife,” said Colin B. Bailey, director of the Morgan Library and Museum. “Their work mirrored the era’s intricate mix of temporal, spiritual and ancient methods for recording the passage of time. The elaborate prayer books, calendars and other items in the exhibition provide a rich visual history of a world at once familiar and foreign.”

The show is divided into five sections focusing on the medieval calendar, liturgical time, historical time, the hereafter (“time after time”) and the San Zeno Astrolabe.

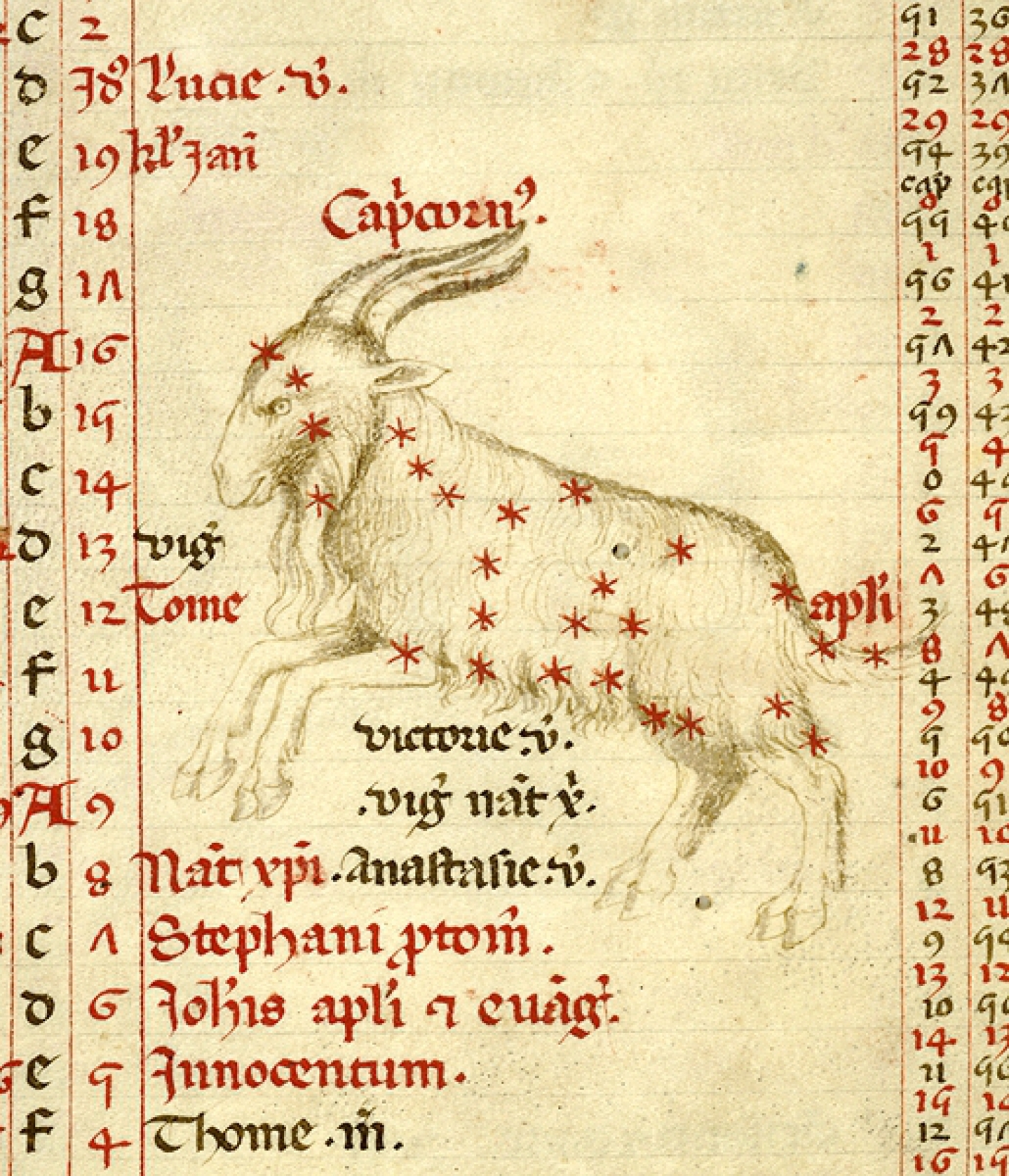

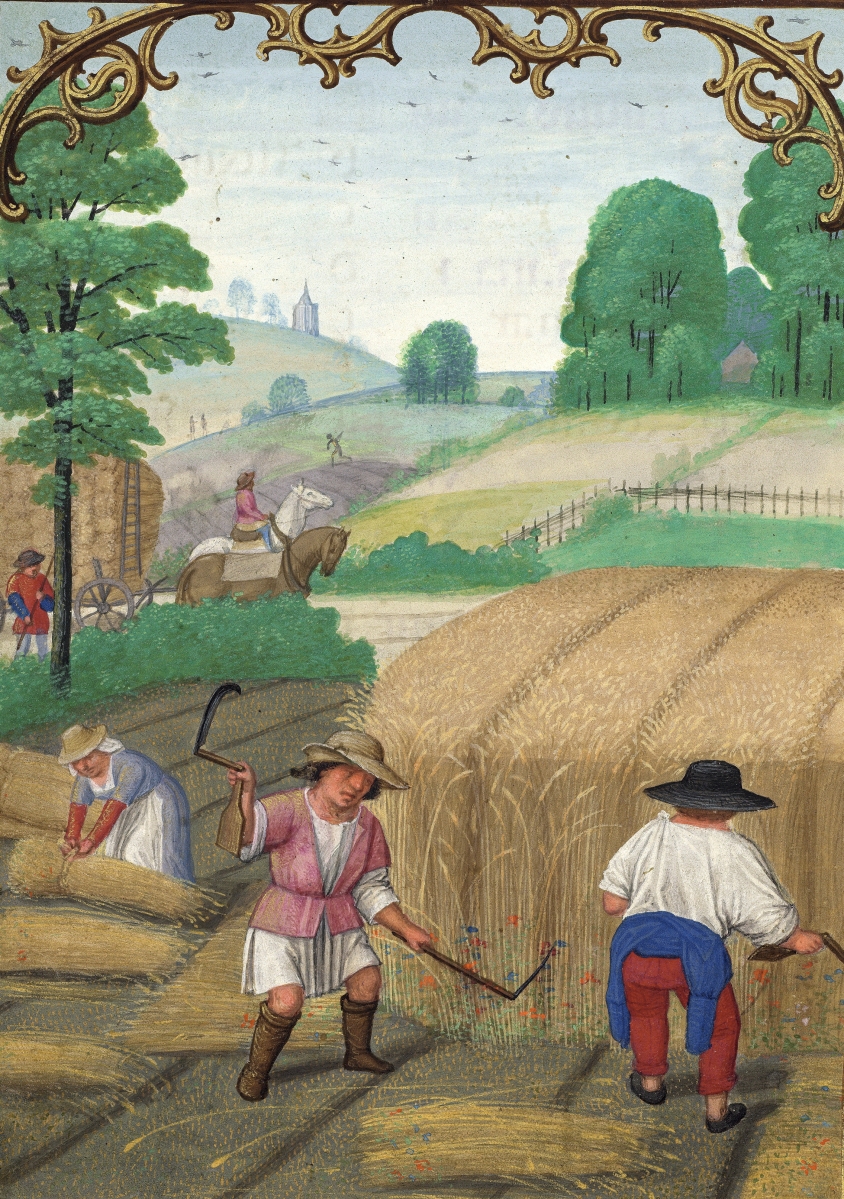

Medieval calendars told time in two ways: through the ancient Roman calendar that Julius Caesar had reformed in 45 BCE and by the feast (usually a saint’s day) celebrated on the day. They appear odd to modern eyes because they lack our sequential numbering; all medieval calendars were perpetual. But they also contained much useful data. Golden Numbers tracking the year’s new moons and Dominical Letters (A through G) tracking Sundays were both used to determine the date of Easter. Calendars also noted each month’s unlucky days and added astronomical information such as the beginning of the summer’s Dog Days.

In addition to the signs of the zodiac, calendars often depicted the labors of each month – for instance, August was dedicated to reaping wheat. By the late Fifteenth and early Sixteenth Centuries, this sole secular element within prayer books was given more focus. In fact, illuminator Simon Bening painted the labors on the folios of the Da Costa Hours as large, full-page illustrations.

Parliament of Heaven and a rare depiction of Limbo, Book of Hours, Northeastern France or Paris, circa 1465, illuminated by the Master of Jacques de Luxembourg. Image courtesy of Dr. Jörn Günther, Rare Books AG.

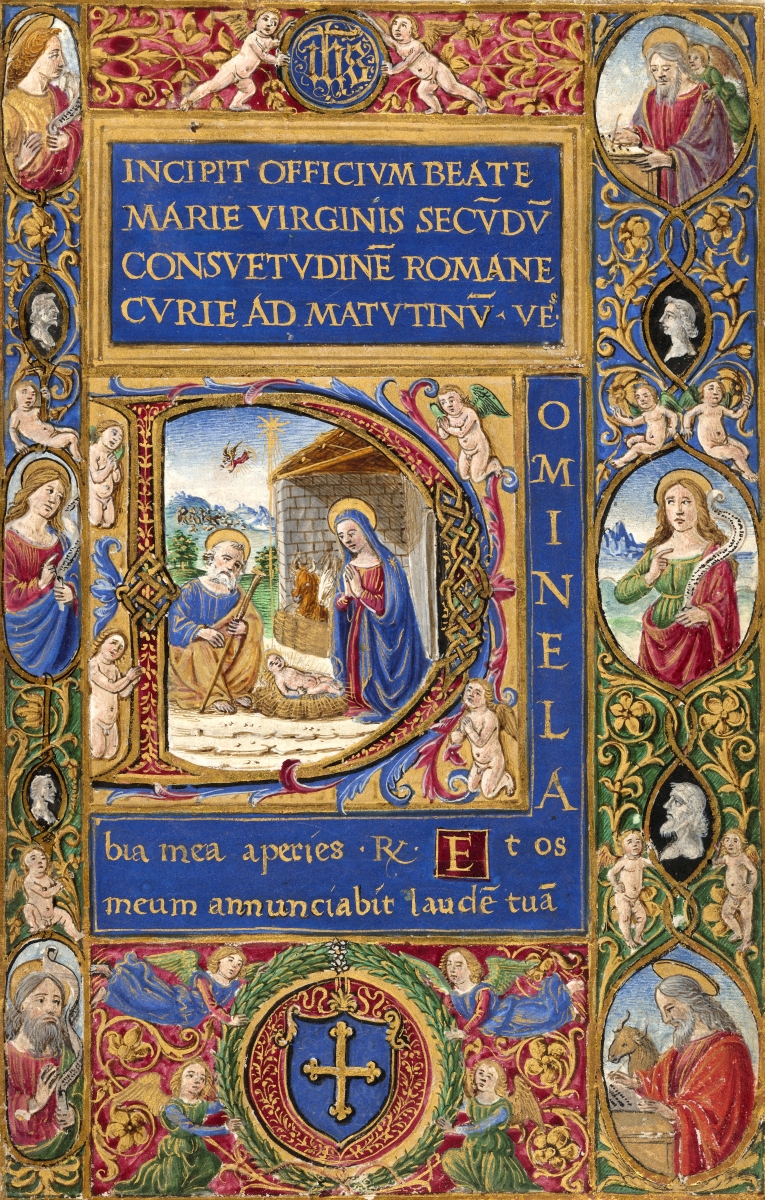

During this period, Europeans used the canonical hours to tell daily time. The medieval day was marked by eight hours, which the Church sanctified with prayer. The prayers became synonymous with the particular times they were recited. Books of Hours enabled laypeople to imitate the clergy and pray throughout the course of the day. A jewel-like Book of Hours illuminated by French Renaissance artist Jean Fouquet will be open to the Visitation, a scene marking the nighttime hour of lauds.

Two overlapping systems were used to structure the year: the temporale and the sanctorale. The temporale consisted largely of feasts celebrating events from the life of Christ. Some feasts had fixed dates, like Christmas; others were movable, like Easter. Feasts of the sanctorale were generally saints’ days, commemorating the days upon which the saints died and entered heaven.

Remnants of medieval timekeeping survive today. The medieval vigil, the commencement of an important feast on the evening before, has become today’s eve, such as Christmas Eve or New Year’s Eve. In The Berthold Sacramentary, a miniature marks Palm Sunday. Distributing blessed palms on Palm Sunday is a medieval practice that continues to this day. Christmas, Valentine’s Day and St Patrick’s Day all come from the medieval way of keeping time as well.

“Now and Forever” is accompanied by the book The Medieval Calendar: Locating Time in the Middle Ages by Roger Weick, which examines vigils, octaves, Egyptian Days and other fascinating mysteries of medieval calendars. It is published by The Morgan Library and Museum and Scala Arts.

The Morgan Library and Museum is at 225 Madison Avenue, at 36th Street. For further information, 212-685-0008 or www.themorgan.org.