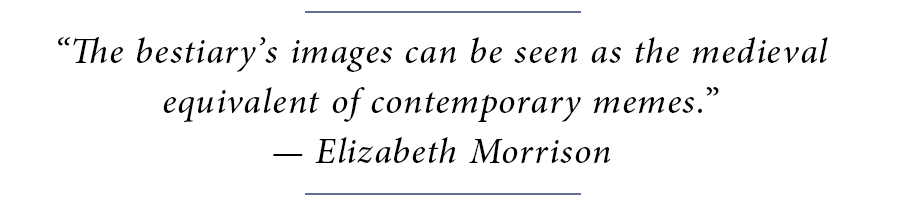

Bestiary, English, about 1225–50. Parchment, leaf 11-5/8 by 7½ inches. Collection of The Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford.

By Rick Russack

LOS ANGELES – Between May 14 and August 18, the J. Paul Getty Museum will present a comprehensive exhibition of the bestiary, the most popular illuminated texts in northern Europe, especially in England, during the Middle Ages (about 500-1500 CE). Examples dating as far back as the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries will be on display. Many have never been published and have been loaned by intuitions around the world.

The bestiary is an illuminated manuscript, with text often in Latin, usually created by monks living in monasteries. It often describes what was believed at the time to be an accurate description of the animal, bird, fish, etc., interpreting each through the lens of Christian belief to include moral or Christian themes. Scholars point out that the importance of the bestiary is not whether the images are accurate, but that they are intended to teach viewers that all creatures are God’s creations. The medieval bestiary had its origins in a Christian Greek text of around the Second Century called the Physiologus or “Naturalist” after the role of its anonymous author.

Many of these manuscripts that have survived from the medieval period are the most lavishly illustrated volumes in European book history. In the bestiary, animals are presented not merely as zoological specimens, but as lessons for moral behavior. They were made for, and could only be afforded by, wealthy nobility or royal families, although the images were often used in churches and seen by worshipers of varying backgrounds.

The Getty’s exhibition will be an unprecedented gathering of bestiaries – there will be about one-third of the known examples dating back to the Middle Ages, including three important examples from its own collection. These books brought to life unicorns, lions and griffins, along with other beasts: both real and imaginary. The widespread influence of these books on medieval and later life, art and culture, will, for the first time, be explored in a major museum exhibition and accompanied by a major catalog.

While most were produced with Latin texts, other cultures produced their own versions in Hebrew, French, Arabic and Mughal, all of which will be on display. The earliest example in the show dates to about 1130 and was borrowed from the Bodleian Library at Oxford.

Medieval bestiaries contained anywhere from a few dozen to more than 100 descriptions of animals, each with an iconic image. Although the essential elements of the text and imagery associated with the beasts remained consistent across time and cultures, the bestiary was not a standardized work. The aim of the stories and illuminations were not to impart factual information or visual accuracy, but rather to convey the wonder, variety and hidden meaning found in the natural world.

The most common bestiary animals, including the lion, unicorn, elephant, pelican, phoenix and dragon, eventually moved from the pages of bestiaries to a wide variety of other types of objects. Long past the bestiary’s primary period of production in the Thirteenth Century, these images were found on ivories, tapestries, metalwork, jewelry, sculpture and objects of personal adornment. Illustrated were birds and fish as well a wide variety of animals of the jungle. Liturgical books, marginal images in devotional manuscripts, late medieval encyclopedias and all manner of secular books drew on the visual language of the bestiary. Medieval maps located the bestiary’s exotic animals in distant lands such as India and Ethiopia.

Many of the illuminated manuscripts were based on biblical stories, several of which have carried on to present day. They also included writings and illustrations of daily life, and these are less well-known. According to Timothy Potts, director of the Getty, “They are primary sources of information, widely disseminated and read; the bestiaries were illustrated collections of real, imaginary and hybrid beasts, many of exotic origin and sometimes entirely fantastic. They give visual form to the creatures believed to inhabit the known world and the distant realms beyond. Both for their artistic inventiveness and for the insights they provide into the medieval imagination, these works are one of the most engaging aspects of medieval art.” A section of the exhibition will also include modern and contemporary works that trace their origins to the bestiary tradition.

Elizabeth Morrison, senior curator of manuscripts at the Getty, thinks, “The bestiary’s images can be seen as the medieval equivalent of contemporary memes. They served as memorable and engaging snapshots of particular animals that ‘went viral’ in medieval culture. The bestiary, in fact, still impacts how we talk about and characterize animals today. The very first line of many medieval bestiaries introduces the lion as the ‘king of the beasts,’ an idea we take for granted today even if most people don’t know its origin. I really got interested in doing this show after we did a small one in 2007 from our own collection.”

The exhibition is organized into five sections. The first section focuses on perhaps the best-known and beloved of the medieval beasts, the unicorn: a white horse with a single horn. The text and images convey the message that the unicorn is a pure but fierce creature that can only be captured by a maiden placed in the forest alone, allowing hidden hunters to come forth and slay their prize for its valuable horn. It is often shown bleeding from the hunters’ wounds. The bestiary interprets this scene as a symbol for Christ, who was born to a virgin, making possible his eventual death and crucifixion. The unicorn became one of the most popular animals in art of the period, largely due to its powerful Christian message, and exemplifies how the bestiary’s texts and images played a vital role in establishing animal stories and their Christian connotations in the minds of widespread audiences.

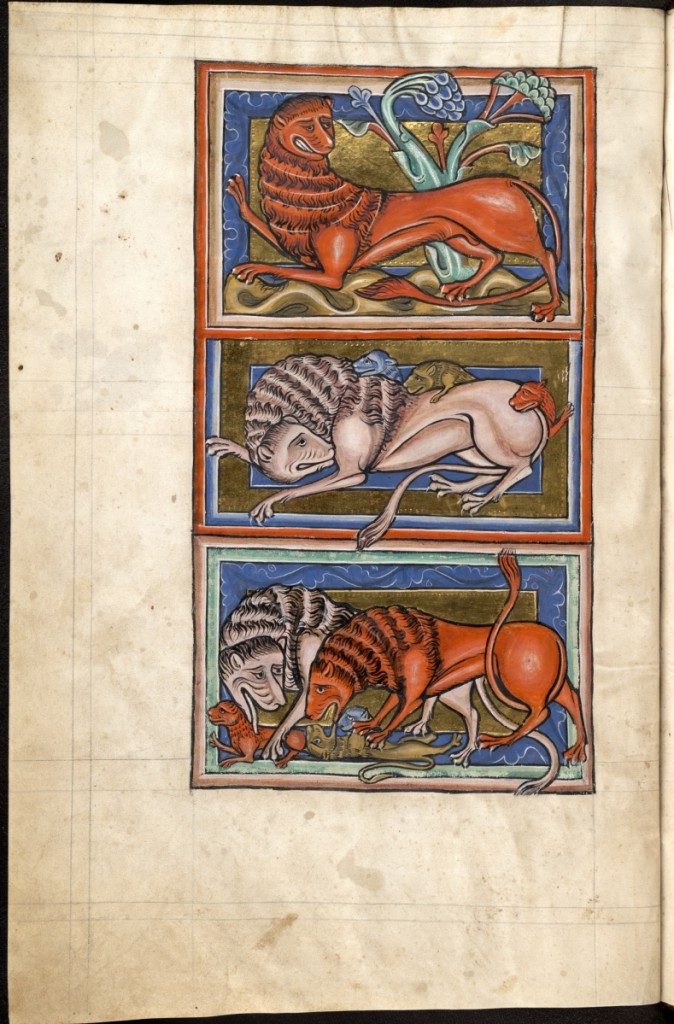

“Bestiaire Fabuleux” by Edmond Variel, Jules-Dominique Morniroli and Maurice Darantière (French), 1950. Ink, closed 15¼ by 11-7/16 by 1-3/16 inches. Collection of The Walters Art Museum. Copyright Jean Lurçat Artwork ©2019 Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris.

Morrison, speaking of unicorns that appear in all early medieval bestiaries, says, “This fabled beast has held the imagination of generations captive for over 2,000 years, although many today would dismiss the legendary animal as no more than evidence of past gullibility, more appropriate to children’s toys and fantasy posters than to the annals of natural history. Yet for those living in the Middle Ages, without the access to travel and instant information that we take for granted, who were they to doubt the existence of the unicorn when it was attested to by authorities, including the Bible, Aristotle and even Marco Polo, who claimed to have seen one with his own eyes?”

The distinctions based on scientific criteria that we make today were irrelevant in the Middle Ages. Questioning an animal’s status as “real” or “imaginary” was not part of the thought process of medieval bestiary readers. The bestiary was designed to impart a largely symbolic worldview based on Christian truths. Some animals were seen as reflections of Christ in the natural world, such as the lion, who would breathe on its dead cubs after three days to bring them to life just as Christ died on the cross and was resurrected three days later. Others replicated virtues or vices common to the human condition, such as the dragon, famed for killing elephants by using its tail to suffocate them – just as the faithful can become suffocated by sin.

The second portion of the exhibition, “The Bestiary,” presents the development of the bestiary’s textual and visual tradition, highlighting a series of animals and their related stories. Although the essential elements of the text and imagery associated with the beasts remained consistent across manuscripts, the bestiary was not a standardized book. The third section, “Beyond the Bestiary,” takes a look at different incarnations of the bestiary’s animals. The bestiary’s stories and images were so popular that medieval artists readily adapted them to a variety of works of art. The fourth section, “Bestiary and the Natural World,” encompasses the use of bestiary material in natural history texts, encyclopedias and maps. The medieval bestiary, while never intended as a scientific work, was borrowed from liberally, much of its lore eventually incorporated into the nascent field of natural history. The final section, “The Legacy of the Bestiary” explores the medieval bestiary’s artistic impact in more recent times on works by modern and contemporary artists such as Pablo Picasso, Alexander Calder, Damien Hirst and others.

“Book of Beasts: The Bestiary in the Medieval World” is curated by Elizabeth Morrison with Larisa Grollemond, assistant curator of manuscripts at the Getty Museum. In conjunction with the exhibition, Getty Publications will release a catalog of the same title edited by Morrison with Grollemond. It has 270 color illustrations and contributions by 26 leading scholars in the field and an extensive bibliography. This volume explores, in depth, the bestiary and its influence on medieval art and culture as well as on modern and contemporary artists.

The J. Paul Getty Museum collects Greek and Roman antiquities, European paintings, drawings, manuscripts, sculpture and decorative arts to 1900 as well as photographs from around the world to the present day. The Museum’s mission is to display and interpret its collections and present important loan exhibitions and publications for the enjoyment and education of visitors locally and internationally. This is supported by an active program of research, conservation, and public programs that seek to deepen knowledge of and connection to works of art. More than six other exhibitions are running concurrently with this one.

The J. Paul Getty Museum is at 1200 Getty Center Drive. For additional information, www.getty.edu or 310-440-7300.