“The Race” by Wharton Esherick, 1925, painted wood on walnut base, 6¾ by 30¾ by 8½ inches. Wharton Esherick Museum Collection. Photo by Eoin O’Neill, courtesy of the Wharton Esherick Museum.

By Madelia Hickman Ring

CHADDS FORD, PENN. — Before there were lifestyle gurus and influencers, there was Wharton Esherick (American, 1887-1970), whose iconoclastic vision and creativity were expressed in a variety of media, including woodcut illustrations, drawings, sculptures, objects and furniture. The father of the Studio Art Movement is being celebrated at the Brandywine Museum of Art (BMA) in collaboration with the Wharton Esherick Museum (WEM) — Esherick’s hillside home and studio, which was built between 1926 and 1966 into the steep, south-facing slope of Valley Forge Mountain in Malvern, Penn. Referred to by the BMA as “an autobiography in three dimensions,” “The Crafted World of Wharton Esherick” brings together selections that span his seven decades of artistic practice, including many pieces that have never been viewed outside of his home and studio.

“The Crafted Word of Wharton Esherick” is curated by Emily Zilber, WEM’s director of curatorial affairs and strategic partnerships, with organizational and curatorial guidance and coordination provided by Amanda Burdan, senior curator at the BMA.

The exhibition evolved over seven years of conversations between the BMA and WEM, evolving from an original idea for a smaller exhibition that would focus on his prints in the BMA’s collection. Zilber further explained, “WEM has been through a tremendous amount of change in the past few years, including celebrating its 50th anniversary in 2022 and opening up rarely seen aspects of our campus, like Esherick’s 1956 Workshop, designed in collaboration with Louis Kahn and Anne Tyng, through new specialty tours. Bringing objects from our collection to a wider audience through a partnership with the Brandywine seemed like a perfect fit for this moment of increased accessibility and celebration.”

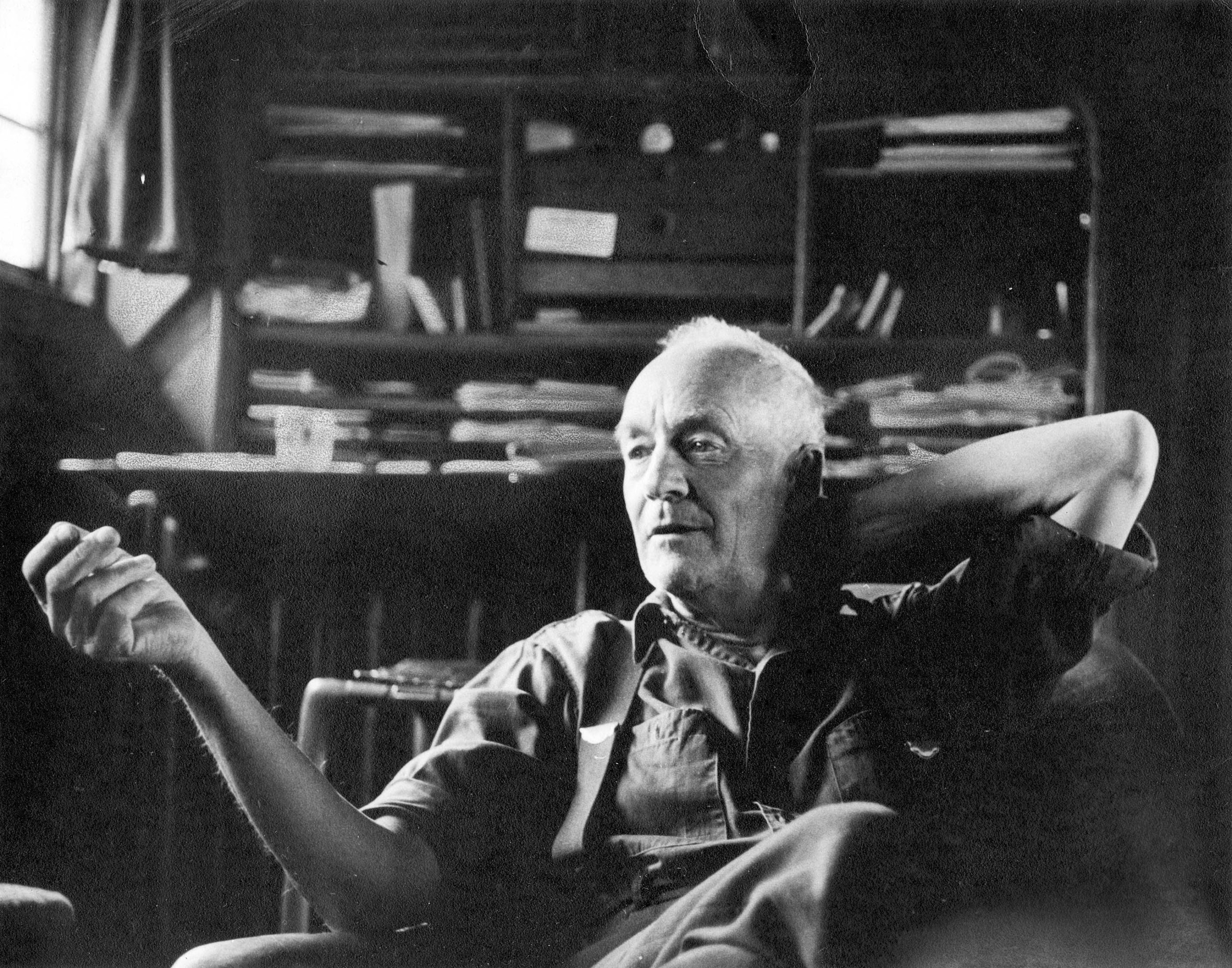

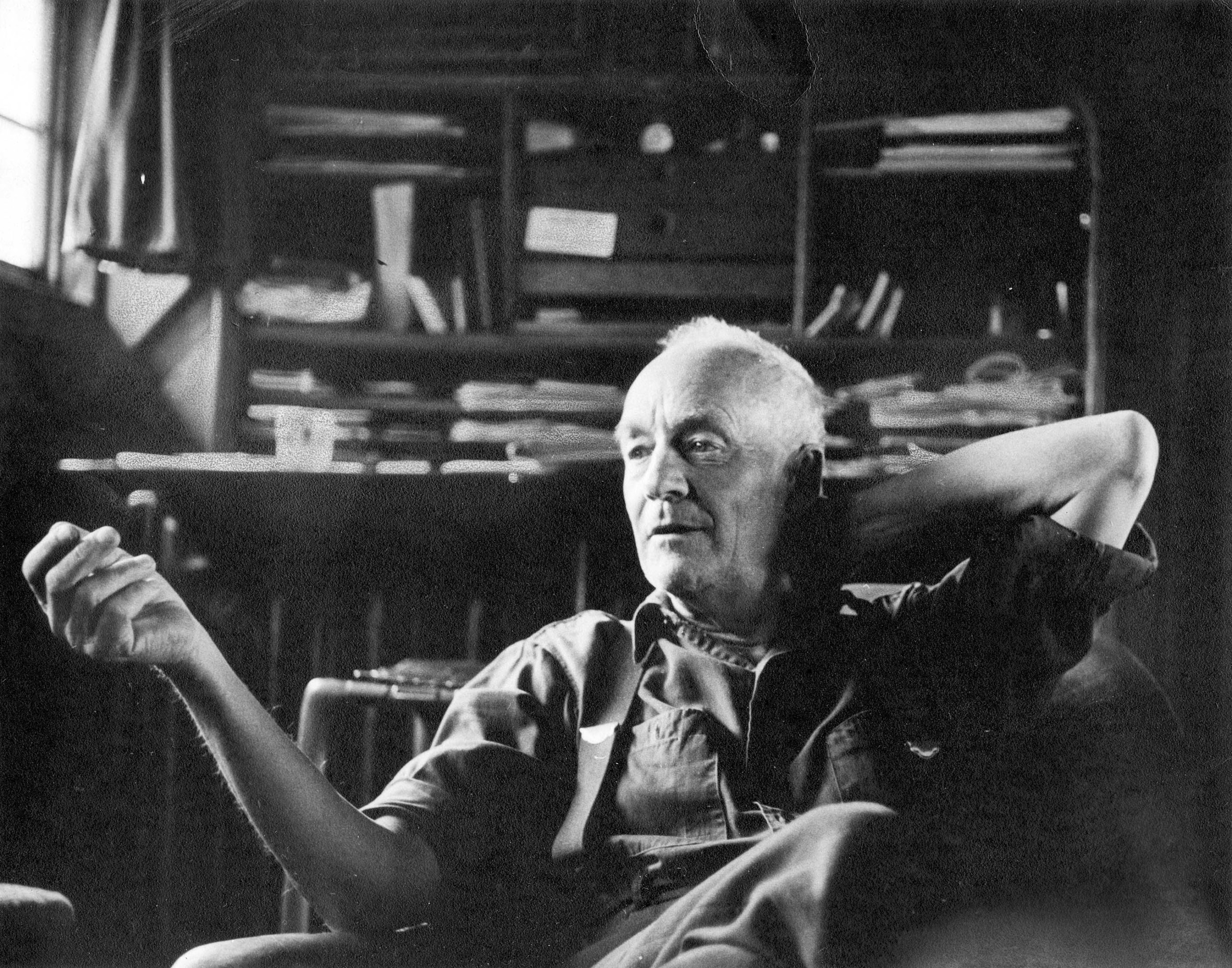

Wharton Esherick, circa 1960. Susan Sherman photo, courtesy of the Wharton Esherick Museum.

Esherick’s work was widely exhibited during his lifetime, including from 1958-59 in New York City in “The Furniture and Sculpture of Wharton Esherick” at the then newly-founded Museum of Contemporary Crafts (now the Museum of Arts & Design) and, in 1972, as part of the Renwick Gallery’s “Woodenworks: Furniture Objects by Five Contemporary Craftsmen.” Posthumously, his works were included in the 2003 exhibition, “The Maker’s Hand: American Studio Furniture, 1940-1990” at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts.

Zilber acknowledges that “The Crafted World” breaks new ground from previous shows. “It represents a new approach to the exhibiting of the artist’s work and the bounty of WEM’s holdings. It is the first exhibition that shows objects from across media drawn exclusively from the museum’s extensive collection of over 3,000 objects. It represents the largest number of works that have ever been on loan from WEM at one time.”

She also notes there were some surprises to the curatorial team as “The Crafted World” and its formulative research developed. “It was certainly not as obvious to us at the start as it is now just how many points of connection there are between the WEM and the Brandywine, and the artists they represent. N.C. Wyeth and Esherick’s birth dates differ by only five years (Wyeth was born in 1882 and Esherick in 1887). Both had connections to the New Hope Group painters, a deep interest in the writing of Henry David Thoreau, and found inspiration in the day-to-day mechanics and materials of rural life. By extension, it became clear that there were a number of artists seeking to leave the city behind and ensconce themselves in creative hideaways close enough to remain in contact with the broader business of the art world but in relative seclusion.”

“Flat Top Desk” by Wharton Esherick, 1929 and 1962, walnut and padouk, 28 by 82 by 36 inches. “Desk Chair,” 1929, walnut, padouk, laced leather seat, 28 by 18 by 18 inches. “Desk Figure,” bronze casting of 1929 Cocobolo original, 10 by 5 by 4 inches. Wharton Esherick Museum Collection. Eoin O’Neill photo, courtesy of the Wharton Esherick Museum.

“The Crafted World” is divided into vignettes, using strategic juxtapositions of artworks, objects, historic photography and other pieces from WEM’s collection to not only explore the power of his vision but define Esherick’s interdisciplinary, integrated approach to living and artmaking as relevant to this moment in history.

Esherick’s home is fundamentally a rural experiment, built by laborers who worked closely with local materials within a landscape of fields, forests and the occasional farmhouse. The vignette titled “Rural and Urban” explores this alongside his ties to urban living and connections with avant-garde artists, cosmopolitan clients and urban artistic movements. His “Flat Top Desk Suite” is one such piece, featuring angular geometric forms that aligned with German Expressionism.

A woodblock print, made in 1923, three years before his studio was built, is titled “Diamond Rock Hill” and shows a view of Esherick’s family home as seen from the planned site of his studio. Nature is a dominant element in the composition and reinforces his insistence of maintaining the rural landscape around his property.

The bridge between Esherick’s two-dimensional and three-dimensional works is explored in the vignette, “Pattern Recognition,” a somewhat surprising title given the unexpected arcs and bends of his oeuvre. Carving frames for his paintings was his first foray into woodworking and he sought to create patterns that enhanced the images housed within them. This would develop into making furniture, sculpture and other three-dimensional forms.

“Moonlight on Alabama Pines” by Wharton Esherick, 1919-20, oil on canvas, carved and gilded frame, 23½ by 17½ inches. Wharton Esherick Museum Collection.

“Moonlight on Alabama Pines” is an early tour de force, ethereally depicting a grove of trees in a frame that has pine needles as its predominant motif. He retains this abstraction even as he moves into three dimensions, notably in “The Race,” a dynamic and colorful version of a child’s game.

By the 1930s, Esherick stopped rendering the human form in a literal way. “Bodies in Space” is another vignette that examines this phase of his artistic development, when he became more interested in how people relate physically to things they use, as well as how furniture is designed. A light pull, rendered in the form of a suspended figure pulling down on a light cord, captures this essence succinctly.

The final vignette, “The Way Things Grow,” represents Esherick’s broader output and ties directly to his career-long interest in the way things grow in the natural world. A music stand, designed for one of his most important patrons and passionate amateur cellist, Rose Rubinson, captures and amplifies the movements she would have made while playing her instrument. The sinuous twists and gentle curves of his “Library Ladder” exemplify this magnificently, seamlessly blending form and function. He made a narrow but impactful leap to his spiral staircases, which the catalog describes as “perhaps the most iconic architectural feature” of his studio; the model for the Hedgerow Theatre Lobby Stair is one of many versions he made.

“Hedgerow Theatre Lobby Stair Model” by Wharton Esherick, 1934, walnut, 26¼ by 14½ by 12 inches. Wharton Esherick Museum Collection.

The BMA’s Burdan, reiterating that “it became clear that there were a number of artists seeking to leave the city behind and ensconce themselves in creative hideaways close enough to remain in contact with the broader business of the art world but in relative seclusion. So much attention has been paid to the role of the city and urban spaces in the development of Twentieth Century American art, but this exhibition reminds viewers of another path that other artists often took.”

“The Crafted World of Wharton Esherick” will be on view at the Brandywine Museum of Art from October 13 through January 19.

The Brandywine Conservancy and Museum of Art are at One Hoffmans Mill Road. For information, 610-388-2700 or www.brandywine.org. The Wharton Esherick Museum is at 1520 Horse Shoe Trail in Malvern, Penn. For more information, 610-644-5822 or www.whartonesherickmuseum.org.