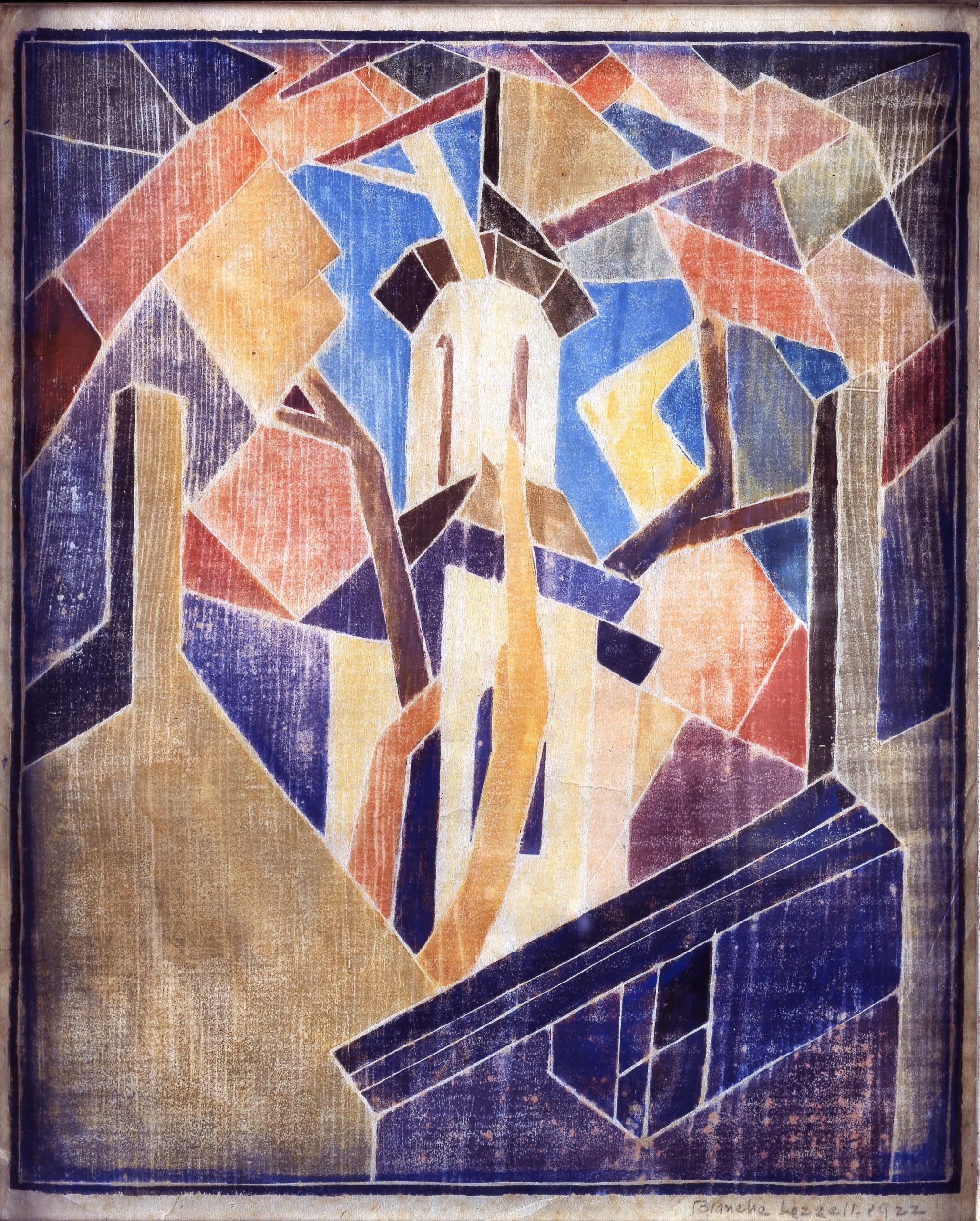

“Still Life” by Blanche Lazzell, 1920, color woodblock print. Art Museum of West Virginia University Collection. Image courtesy of the Art Museum of West Virginia University.

By Andrea Valluzzo

GREENWICH, CONN. — Blanche Lazzell is well known in her native West Virginia as well as on and around Cape Cod, where she made art for more than 40 years, but elsewhere her contributions to Modernism have been largely unrecognized. If one is pressed to name an American modernist, chances are what first comes to mind are artists like Edward Hopper, Georgia O’Keeffe, Arthur Dove, Charles Demuth and Stuart Davis, but not Lazzell. A new exhibition aims to change that.

Born in West Virginia, Lazzell (1878-1956) pursued her arts education locally before making the critical decision to attend the Art Students League in New York City. Heading to Paris in 1912 was also important to her evolution as an artist; there, she soaked in the sweeping changes the art world in Europe was experiencing at the turn of the century. Her first European foray saw her studying at the Académie Julian and Académie Moderne. Abstraction and Cubism in particular were elements the artist keyed into while she was there and which she brought back home a year later when she settled in Provincetown, Mass. She helped usher in — and translate — a wave of European Modernism to the United States.

“Blanche Lazzell: Becoming an American Modernist,” on view February 6 through April 27 at the Bruce Museum, is the first major solo museum retrospective devoted to the artist in two decades. Organized by the Art Museum of West Virginia University (WVU) in Morgantown, W.Va., which loaned artwork from its sizable holdings of Lazzell’s works; it is likely the largest ever showing of her work — even including shows held during in her lifetime. It’s also long overdue. Historically, museums have favored male artists, but in recent years, exhibitions have grown increasingly diverse, and early women artists are at last getting their due.

“Shell” by Blanche Lazzell, 1930, oil on canvas, 16-3/16 by 20 inches. Art Museum of West Virginia University Collection. Estate of Blanche Lazzell.

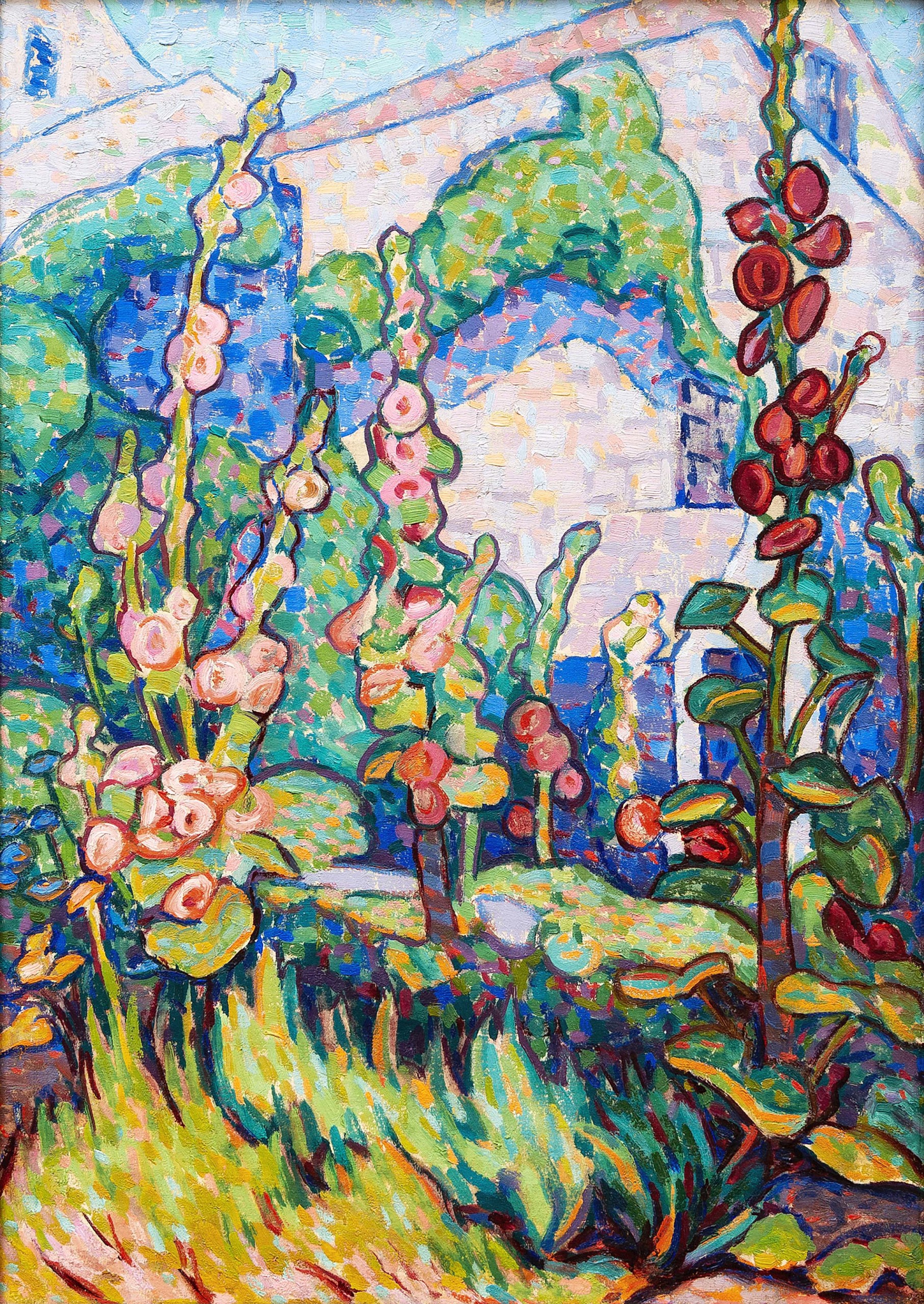

In 1916, Lazzell teamed up with several artists who displayed their color woodblock works to create the Provincetown Printers Group, the first color woodblock society in the United States. Lazzell soon distinguished herself with her white-line color woodblock prints but she also enjoyed success with her paintings that increasingly became more abstract as she moved through her career. While her prints are what many today seek out, she always considered herself a painter at heart and even approached her printmaking with painterly techniques. Her prints and paintings share an affinity for geometric abstraction expressed by her use of bold colors and flat, simplified forms in the Japanese tradition of ukiyo-e prints. Starting in the late 1910s, she began simplifying her iconography in her prints and paintings while simultaneously creating compositions that grew more abstracted as well as sophisticated.

“With so few people that know Lazzell’s work, I wanted to really make the exhibition retrospective in nature. Her color woodblock prints are really what’s most popular and well-known, but she considered herself first and foremost a painter,” said Bob Bridges, curator at the Art Museum of West Virginia University. “She considered those woodblock prints as paintings because of the nature of how they were made. She was painting directly on a wood block and building up layers of color like you would in a watercolor or an oil painting.”

“I thought it was really important for people to see her ability to work through color, compositions and design principles in these works because that is ultimately what compelled her to make work — color, relationships and design organization of the compositional elements,” he added.

“Abstract Tempera No. III,” a study for “Painting X,” by Blanche Lazzell, 1927, tempera on paperboard. On loan, courtesy of Clarksburg‑Harrison Public Library.

Lazzell certainly did not invent the technique of white line color block printmaking, which began in Provincetown, but was one of its most ardent devotees and a master of this form. “This was one of the first printmaking techniques that’s really unique to the United States, and it involves cutting a design into a soft block of wood and then you ink each section, one by one,” said Jordan Hillman, curatorial associate at the Bruce Museum. “The result in a print is sort of painterly… it’s not necessarily 100 percent reproductive in the way that other prints might be because you are sort of hand painting each section, pressing the paper down, lifting up and then applying the next color, pressing down and lifting up… so it has these white lines between these painted areas of color.”

Lazzell’s prints typically feature hard-edged abstraction but the way she applied wet washes of color gave them a translucent “glowing” quality most prints do not have, Hillman adds.

Her prints are also unique in that they are not made in editions in the way multiples often are, in groups. In some cases, such as “Among the Wharfs,” she only ever pulled one print from the image, Bridges noted.

The exhibition features more than 60 prints, paintings and works on paper tracing the artist’s evolution. There are even several examples on display that include a preparatory drawing for a composition, the woodblock print and a painting of the same scene. “I think that one fascinating aspect of the exhibition is that people really get to see her process — you can see all the changes that she is making or how her designs are moving from her original conception to the final version of the work,” said Hillman.

“Painting X” by Blanche Lazzell, 1927, oil on canvas, 50-3/16 by 36-1/8 inches. Art Museum of West Virginia University Collection. Estate of Blanche Lazzell.

Bridges edited the definitive monograph on Lazzell in 2004 and has organized several small exhibitions on the artist before this one. He was excited to have this travelling exhibition appear at large museums outside WVU, which mainly attracts a regional audience. “I really want this to be an introduction of Blanche Lazzell, for people to be able to really see probably the largest exhibition of her work,” he said. “I feel like people who know her work will sort of be a little bit surprised and in awe of the depth and quality, and I think that folks who discover her for the first time will come away thinking she was an important artist.”

Historically, few female artists have made it into the art canon and there were several things that worked against Lazzell. She did not have a key patron or champion in New York, promoting and selling her work in the way that Alfred Stieglitz advocated for Georgia O’Keeffe. She also concentrated on smallish works — easy to frame, wrap and ship for inclusion in exhibitions — and prints, which unfairly have had the connotation of being second tier to paintings. Another contributing factor is that after she died in 1956, her family cleared out her Provincetown studio and brought all her art back to West Virginia. The Boston MFA, not surprising given its proximity to Cape Cod, retained an impressive collection of Lazzell’s prints, but most of her works went back south; West Virginia University has more than 200 works by Lazzell.

“Hollyhock” by Blanche Lazzell, 1917, oil on canvas, 25-5/8 by 18-1/8 inches. Art Museum of West Virginia University Collection. Gift of Nancy Watkins in memory of James F. McKinley and Nancy W. McKinley. Estate of Blanche Lazzell.

Arranged chronologically, “Becoming an American Modernist” highlights the interplay between Lazzell’s prints and paintings as viewers are taken through her career to see how her artistic vision developed. Unique to its presentation at the Bruce is the addition of a transitional painting, “Shell,” that Lazzell did in 1930. The Roaring Twenties was Lazzell’s most fertile and productive era. She returned to France in 1923 and spent almost a full year studying Cubism with notable artists like Fernand Léger, André Lhote and Albert Gleizes. “She had always been interested in Cubism since her first visit to Paris but in the 20s, she decided to devote herself to these principles,” Hillman said. “‘Shell’ is her first work in the exhibition from the 1930s, and you can really see her combining these principles of abstraction that she worked through in the 1920s.” In this painting, which blurs the lines between representation and abstraction, Lazzell set a conch shell accompanied by a few flowers against a nexus of multi-patterned planes — the hallmark of her most ambitious paintings. Nature figured prominently in her art, and she found much inspiration in the scenery that surrounded her Provincetown home and studio.

By the 1950s, she had embraced abstraction full-on after a lifetime of experimentation, which viewers can note in works like “Planes II,” a 1952 color woodblock print. It features geometric shapes in her signature bright color palette with reds, greens and yellows divided by her signature thinly incised white lines.

Bridges, who has been fascinated by Lazzell’s work since first seeing one of her 1918 prints more than 20 years ago, succinctly sums up her appeal: “It is the work first and foremost. She is just a really interesting, committed artist that started making abstract art when few people could make heads or tails of that concept.”

The Bruce Museum is at 1 Museum Drive. For more information, www.brucemuseum.org or 203-869-0376.