TAOS, N.M. – Storied names: Sharp, Couse, Blumenschein, Dunton, Phillips, Berninghaus. They founded the Taos Society of Artists (TSA) in 1915. As time went on, other luminaries were voted in: Hennings, Ufer, Higgins, Adams, Critcher, Rolshoven. Then there were associate members, among them Gustave Baumann, Robert Henri and John Sloan.

Two of the Taos pioneers, Eanger Irving Couse (1866-1936) and Joseph Henry Sharp (1859-1953), ended up living and working next door to one another. After decades of basic preservation followed by years of restoration, Couse’s home and the Couse and Sharp studios have become the Couse-Sharp Historic Site. What follows is a conversation with executive director and curator Davison Koenig (DK) and Virginia Couse Leavitt (VCL), granddaughter of the artist.

– James D. Balestrieri

How did E.I. Couse and J.H. Sharp come to live next door to one another?

VCL: In 1906, the Couses bought their first Taos house, west of Doc Martin’s and across the street from the home of Bert Phillips, near the intersection of Pueblo Road and Bent Street. Couse first met Sharp that summer. Sharp, who called Taos his “first love and stomping ground,” in 1908 bought a house on Kit Carson Road. The following year, Couse sold his Pueblo Road house and moved to property on Kit Carson adjacent to Sharp’s, where there was plenty of room to add a large studio. This was the beginning of a long and close relationship between the Couse and Sharp families. It was common for fellow members of the Taos Society of Artists to gather there in the evening to discuss art and enjoy the spectacular view.

How did Couse and Sharp interact? Anecdotes?

VCL: Couse and Sharp were friends and had an easy relationship. One day in the 1920s, John D. Rockefeller knocked on Sharp’s studio door, but Sharp, being deaf, did not hear the knock. He usually relied on his little dog to alert him to visitors. He believed the dog had a sixth sense as to whether the visitor might be a buyer or only a looker, raising either his left or right ear according to the situation. In this case, however, the dog gave the wrong signal and Rockefeller continued to Couse’s studio, where he bought three large and 12 small paintings. That afternoon, Couse teased Sharp good-naturedly about the situation. Of course, Rockefeller returned a little later to buy paintings from Sharp as well.

Can you share the history of the compound?

VCL: The Sharp house had purportedly once been a dance hall. On the west side was an orchard that led to the large studio that Sharp built south of his house in 1915. In 1918, the Couses and Sharps carried out a joint landscaping project on their properties facing Kit Carson Road. At this time, the Sharps also added a portal to the east side of their house. The Couse house had started as a one-room structure built by Pedro Luna in 1839. Rooms were added to it over time by several notable owners, and it had seven rooms by the time the Couses bought it in 1909. The Couses kept a winter studio in New York until 1928, when they decided to live in Taos year round. The last changes were made in 1930 to accommodate living and work space for their son, Kibbey, who moved to Taos to care for his father after his mother’s death. The Sharps, who had no children, considered the Couse offspring their own.

Virginia Couse Leavitt has been instrumental in the development of the Couse-Sharp Historic Site. How would you describe her role?

DPK: Kibbey loved the Taos home and wanted to keep it as it was in his youth, so he did not allow changes after his father’s death in 1936. Kibbey’s daughter, Virginia, who became an art historian, and her husband, Ernest Leavitt, a museum curator, were in a unique position to understand its historical importance and guide the family in its preservation efforts. Kibbey sold the Sharp house in 1960 to the late Ivan Rosequist, who reopened it as the Mission Gallery. Art dealer Rena Rosequist, Ivan’s widow, presented the Couse Foundation with the opportunity to reunite the properties when she closed the Mission Gallery late last year.

Are there paintings by Couse and Sharp featuring rooms in the houses, their studios or gardens? Are any of these works in the house now?

DPK: Yes, a beautiful little oil Couse did of the house and his wife’s garden is hanging in the studio. In Sharp’s studio, we can see a wonderful painting depicting his sumptuously furnished sitting room. Numerous paintings at the site depict interiors of the studios showing models using clothing, pottery and other materials, such as the dragonfly elk robe given to Sharp by Chief Flat Iron.

What is in the works for the Couse-Sharp Historic Site?

DPK: Our vision is to become the center for scholarship of E.I. Couse, J.H. Sharp and the Taos Society of Artists. The Couse Archive includes 8,000 photographs taken by the artist as studies for his paintings, plus letters, sales and exhibition records, sketches and many other materials. We are currently cataloging the recently donated papers of TSA scholars Dean Porter, Elizabeth Cunningham and Robert White. We will be building scholar-in-residence and artist-in-residence programs to make the archives more accessible to a wider audience. The Lunder Foundation of Portland, Maine, provided the initial major grant for the research center that will bear its name. Our goal is to open the new facility – including a library, offices, storage and an exhibition space with regular public hours – in the summer of 2021. The importance of bringing the archives of these significant American artists to Taos in one dedicated space cannot be overemphasized. I am also excited about the next generation of Native scholars who may research further the relationships between the artists and their models and perhaps record the oral histories from Taos Pueblo before those stories are lost. We are in the midst of major capital and endowment campaigns to help implement these plans.

How do you envision the role of the Couse-Sharp House in relation to the other artists’ homes, museums and Taos Pueblo?

VCL: The many museums and cultural sites in the Taos area each have unique roles to play. Taos Pueblo, a World Heritage site, is of prime importance. The Couse-Sharp Historic Site is perhaps the best-preserved historic artist’s home in the country. The dining room, living room and studio are furnished as they were at the time of Couse’s death. His paintings hang throughout the house, including not only his Indian pictures, but also earlier works from his years as a student in Paris. Additionally, the house contains the family’s collection of Hispanic santos, Pueblo pottery, Native American clothing and beadwork. The machine shop remains as it was in 1937.

What is your background?

DPK: Long story short, I was previously the curator of exhibits at the Arizona State Museum at the University of Arizona in Tucson. Ernie Leavitt, Virginia Couse Leavitt’s husband, was my predecessor at the museum. Ginnie and Ernie are responsible for the preservation of the Couse-Sharp Historic Site and for the creation of the Couse Foundation in 2001. I was hired to create an interpretive plan for the Sharp studio. After receiving funding from the Tia Collection and the Charlie Russell Riders Foundation, I oversaw the renovation of the studio to return it to the original character of 1915 while simultaneously creating a secure museum environment. A year later, I was hired as executive director and curator.

Your wife, Susan Folwell, is a fantastic Santa Clara Pueblo ceramic artist. How does she influence your thinking about the Couse-Sharp House?

DPK: Susan has recently been drawing inspiration from the immense body of work created by the Taos Society of Artists. She has taken their bold graphic imagery and reinterpreted it. Her work has inspired me to find more ways for Native artists, researchers and scholars to engage with the Couse-Sharp Historic Site. An effort in that direction, the exhibition “Full Circle: Taos Pueblo Contemporary,” is on view here through October 3.

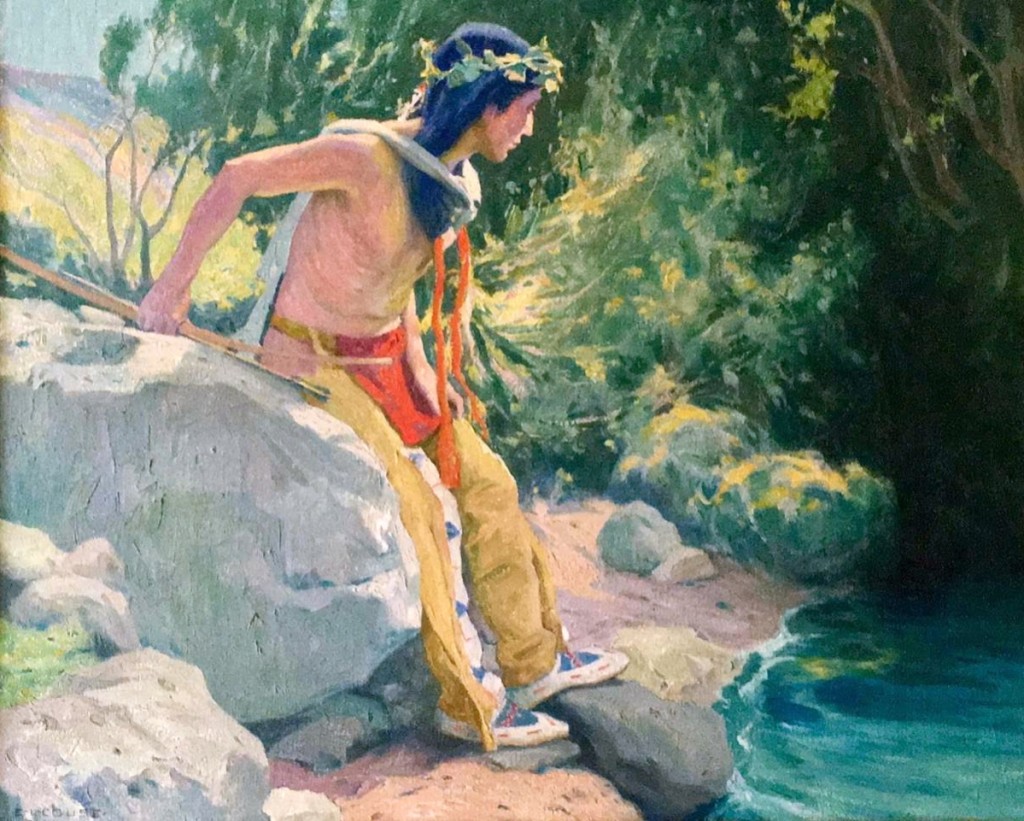

Who were the models Couse, Sharp and other TSA artists worked with?

VCL and DPK: TSA painters developed close relationships with their models. Couse used a number of models, but his two favorites were Jerry Mirabal and Ben Lujan. They appear either separately or together in a majority of Couse’s paintings. Nine-year-old Ben was introduced to Couse in 1902 by his uncle Juan Concha. Ben considered the Couses his adopted parents. Jerry Mirabal began posing for Couse in 1908. He was very handsome and a superb model but had an erratic personality. Jerry posed for Sharp and for other artists as well. Sharp used a variety of other Taos models, including Soaring Eagle, Hunting Son and Bawling Deer, many of whom would drop by the studio, bum a smoke and proceed to critique his work.

Can you take us on a tour of the Couse-Sharp Historic Site?

DPK: The Couse-Sharp Historic Site is perhaps the last authentic glimpse into the lives of the pioneering artists of Taos. These artists created what may have been the most important American art colony and changed our perceptions of America and the West. A scheduled docent-led tour of the Couse-Sharp Historic Site lasts up to two hours and touches on the frontier days of Taos, beginning with the 1835 Luna chapel, once the entrance to Taos along the Santa Fe Trail. The tour proceeds to the portal and gardens. The gardens are the first ornamental displays in Taos, designed and built by Virginia Couse with Ben Lujan. Next is the perfectly preserved Couse home, shuttered after the artist’s passing. The sanctum sanctorum is his studio. Stepping back outside, we pass a replica of Sharp’s Crow-style teepee, which he set up every summer, just as we do now. We marvel at Sharp’s two-story studio. It’s a voluminous space, with the largest collection of J.H. Sharp artwork, ethnographic material and ephemera on display anywhere.

The Couse-Sharp Historic Site is at 146 Kit Carson Road. For more information, www.couse-sharp.org or 575-751-0369.

Playwright, author and critic James D. Balestrieri is director of J.N. Bartfield Galleries in New York City.