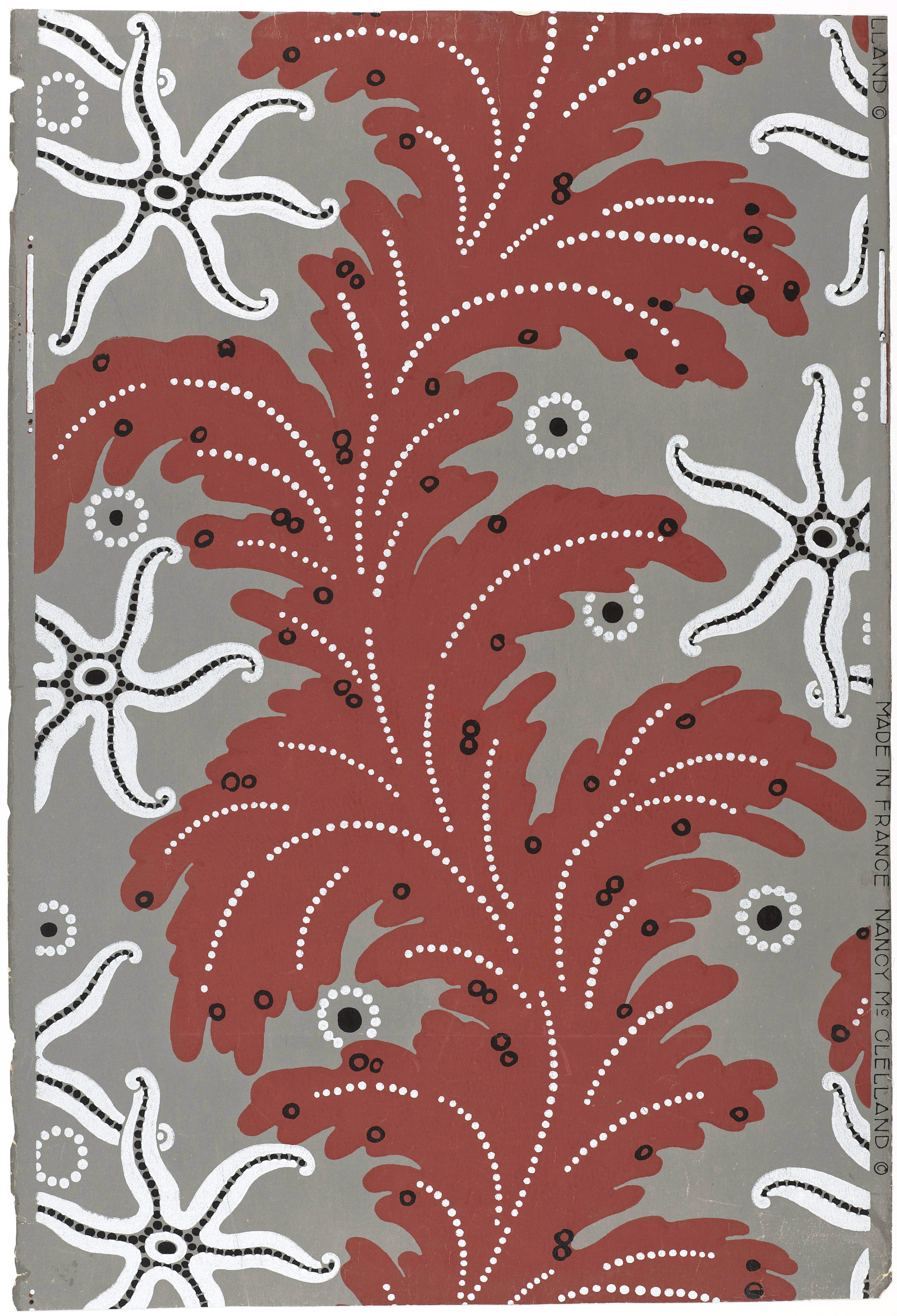

Sidewall, by unknown French maker, 1920-1925, distributed by Nancy McClelland, Inc., block print on paper, 29.1 x 19.5 in. (74 x 49.5 cm). Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, Gift of Nancy McClelland, 1945-3-10. Photo credit: Matt Flynn © Smithsonian Institution. © Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum / Art Resource, NYC.

By Karla K. Albertson

NEW BEDFORD, MASS. — While seaweed in cultural cuisine has become a delicious standard, at first thought seaweed and art seem an ocean apart. But thinking on it, more and more examples come to mind. The New Bedford Whaling Museum has gathered the most lively art and artifacts based on the subject in the Wattles Gallery for a new exhibition, “A Singularly Marine & Fabulous Produce: the Cultures of Seaweed” that will be on view from June 16 to December 3.

Easy to examine along beaches, the common marine plant exerts a mysterious pull which naturally led to scientific study in the Nineteenth Century. But the focus of the exhibits on display is to celebrate the material as a source of artistic inspiration. The title description of it as a “marine & fabulous produce” comes from no other than Henry David Thoreau (1817-1862).

The show was assembled by two curators: Naomi Slipp, the Douglas and Cynthia Crocker endowed chair for the chief curator at the Museum and Maura Coughlin of Northeastern University. Speaking with Antiques and The Arts Weekly, Slipp said, “We’ve been working on the exhibition almost two years. It sprang out of an incredible painting we have in our collection — a painting by Clement Nye Swift of “Seaweed Gatherers” in Brittany. It is more than 90 inches wide, a painting exhibited at the Paris Salon in 1878. A very spectacular work and the entry point for this topic.”

“Seaweed Gatherers” by Clement Nye Swift (American, 1846-1918), 1878, oil on canvas, 41 by 93 inches. New Bedford Whaling Museum, Gift of the Russell Memorial Library of Acushnet, Massachusetts, 2015.

Born in 1846 in Acushnet, Mass. — just to the northeast of New Bedford — Swift studied painting at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris. His best-known works were executed after moving to Brittany in 1870 where he joined an artistic community in the coastal town of Pont-Aven. That was where he created the marine views exhibited in Paris. When he returned to Acushnet in 1881, he turned to writing stories and poetry and remained there until his death in 1918.

Slipp continued, “My research has been in the intersections between art and science, especially around the coast. I knew there was a really rich body of scholarship and some incredible works of fine arts, material culture, and decorative arts that could make up an exhibition. We started on the project soon after I began at the museum in September 2021.”

In order to assemble an exhibition with the scope they envisioned, the curators sought works from private collections and well-known institutions — about 30 different sources in all. The lenders range from Historic New England and the Newport Historical Society to Mystic Seaport, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Cooper-Hewitt, the Smithsonian, the Portland Museum of Art in Maine, Winterthur in Delaware and the New York Yacht Club.

Seafood plate, from the Rutherford B. Hayes Presidential service by Limoges, Haviland, and Company (French, founded 1842) and Theodore Russell Davis (American, 1840-1894), circa 1880, porcelain with enamels and gilding, 9 by ½ inches. Rhode Island School of Design Museum, Providence, RI, Gift of Christopher Monkhouse, 2003. Image courtesy of the RISD Museum.

“It’s exciting to bring all these things together from lots of separate places and stage a conversation between them,” said the curator. “You begin to understand seaweed and how it inspired the creation of many different kinds of works.”

Slipp explained how the organization of the show helps tell the underlying story: “Our exhibition space is about 3,000 square feet. Seaweed has deep, deep cultural significance in lots of different global communities. So, one of the first points we had to make was about the geographic range of the exhibition and the time period that we would cover. Because we were using Swift’s painting as the centerpiece of the exhibition, it seemed to make sense to create a triangle of the Atlantic between New England and France and we decided to also think about the southeast coast of England, because of the rich early photographic work that was happening there and the ceramic tradition.”

A lot of the serious and amateur phycologists — those who explore the science of algae and seaweed — were also working in England and their results appeared in illustrated publications in the 1800s. These prints proved an inspiration to many branches of the ceramics industry — where you find seaweed along with related shells and coral, painted, molded and suggested on many different forms. The show has examples from England, France and the United States. Any pottery collector can pull something from his holdings, such as English producer James Dodson’s relief-molded “Seaweed” jug, which took its place next to the lily and tulip themes.

Jug and basin, made by the Criel Factory (Creil-sur-Oise, France), 1805-1815, earthenware (mochaware) and lead glaze, jug: 10-7/8 by 6 ¾ by 4-7/8 inches; basin 3 ¼ by 13 ¾ by 9 ½ inches. Winterthur Museum, Gift of Jonathan Rickard, 2000. Image courtesy of the Winterthur Museum.

Slipp’s only regret is that there is so much more seaweed to cover, such as works from Asia or the Indigenous baskets made in Washington state: “There were pieces we had to make decisions about, recognizing that we wanted to maintain a tight story for visitors that would fit into our space. Specifically in the installation, people will enter the exhibition and will be invited to think about the people who collected seaweed.” Just as people collected flowers and plants to press into albums, there is a scrapbook of pressed seaweed, loaned by the Mystic Seaport Museum.

She continued, “Then we move into thinking about more local landscapes in New England and expand outward to think about English traditions, decorative arts, industrial applications, contemporary art. But the entry point is really thinking about this moment where Swift sees this tradition in Brittany, he paints it, his peers are painting it, images are being circulated in Harper’s Weekly and in major journals for international readers. Hopefully, that sets the stage for visitors to understand why it resonated with him.”

Other exhibits not to be missed are the period photographs, such as an image by Robert Swan Gifford (1840-1905) of “Boy Forking Seaweed into Cart” from the museum’s own collection. There is also a cabinet card from around 1880 of a woman from Boston wearing a seaweed costume with little fish hanging off. Taken by Amory Nelson Hardy (1835-1911), the photo cues the questions who? And why? Perhaps a theatrical performer?

“Woman Wearing a Seaweed Dress” by anonymous maker, 1870s or 1880s, cabinet card, 4 ¼ by 6 ½ inches. Image courtesy of a private collection.

In addition to the physical objects in the gallery, the show will make its permanent mark on scholarship with a catalog featuring essays from 12 interdisciplinary authors who examine seaweed from every angle possible — as a continuing catalyst for artistic inspiration, as a material, as a sustainable food source. As recent news reports have made clear, seaweed is certainly plentiful, floating offshore.

The museum website — www.whalingmuseum.org — has a list of activities connected to the show, including two editions of the “Seaweed Roundtable” led by Naomi Slipp. The first on August 3 focuses on “Science and Food,” while the one on October 5 explores “Arts and Culture.”

The New Bedford Whaling Museum is at 18 Johnny Cake Hill. For additional information, 508-997-0046.