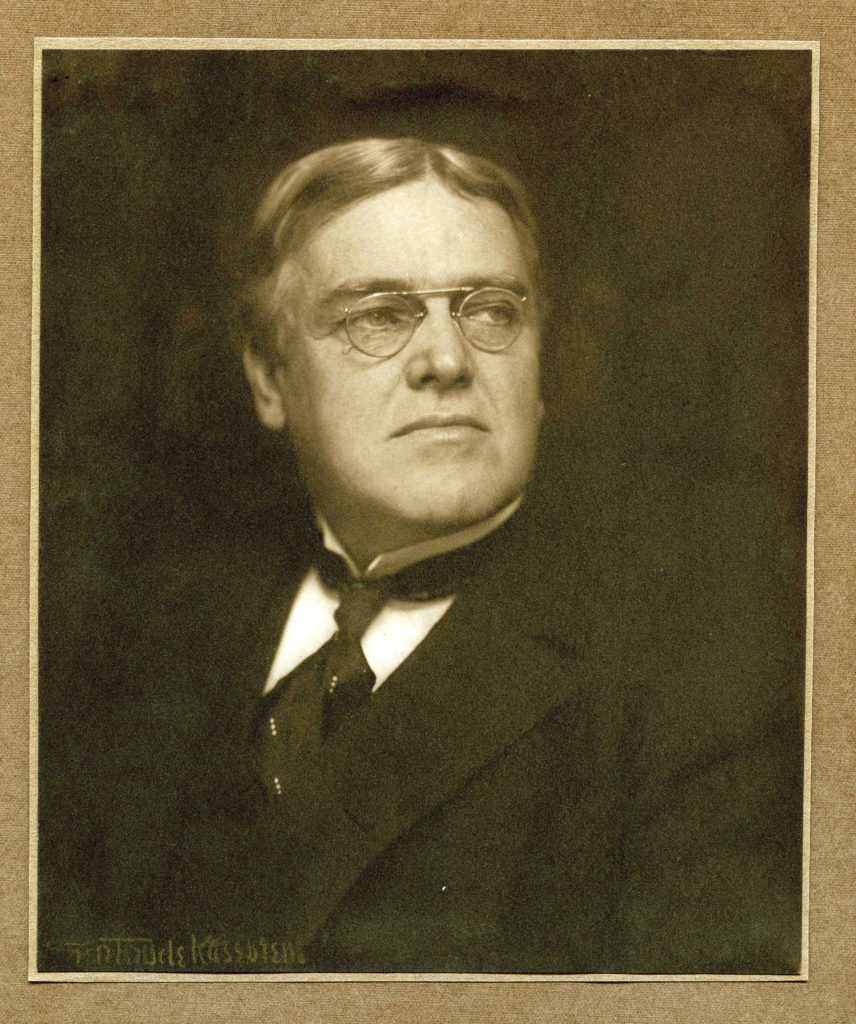

Alfred Atmore Pope, 1902-05.

By Kristin Nord

FARMINGTON, CONN. — The introduction to Alfred Atmore Pope’s life and work currently on view at Hill-Stead Museum will come as a revelation for aficionados who thought they knew the house museum’s story well. Since the museum opened its doors to the public in April 1947, its primary focus had been on Theodate Pope Riddle, Pope’s daughter and one of the country’s first licensed women architects.

Dr Anna M. Swinbourne, Hill-Stead’s executive director and chief executive officer, found it shocking that no one had studied Pope seriously as a collector “or even written more than a biographical sketch of him.” Over three years, she and staff have dug into his story, with the end result, “Alfred Pope: An Evolution of Ingenuity,” a double-phased exhibition that explores both the nature of the highly successful businessman and the development of his magnificent collection of modern European art. Pope’s collection clearly ranks in quality with those of the Havemeyers of New York and the Palmers of Chicago, Swinbourne said, and yet very little has been known about the quality and scope of his collection — until now.

On view through April 22, in Hill-Stead’s new award-winning gallery, the first phase of the exhibition introduces visitors to Pope’s biography and probes his character traits. Pope had forged a stellar career in the industrial iron industry through talent, grit, and an intensive six-day-a-week work ethic. But he was also a boss and colleague lauded for his artistic abilities and his philanthropy. He had drawn upon the values of a humble Quaker beginning and became a lifelong learner.

The Popes rose high in Cleveland society when he embarked upon a 10½-month Grand Tour in 1888-89. It was the first of many visits the family would make to Paris, and with the purchase of a Monet seascape, his appetite was whetted. During his primary collecting years he focused intently on the work of European modernists. “His inimitable curiosity and wisdom, together with the varied totality of his accomplishments, are what made him so extraordinary,” Swinbourne writes.

“Étretat: Upper Cliff, Stormy Weather” by Claude Monet, circa 1884-86. Collection Tom and Nan Riley, United States.

While Hill-Stead had a basic list of original purchases, it took committed detective work to root out mistakes and to locate where many works had landed. In the second phase of the exhibition, which opens to the public on April 27, visitors will have a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to experience many of these masterworks as they were grouped, circa 1910, on the home’s interior walls.

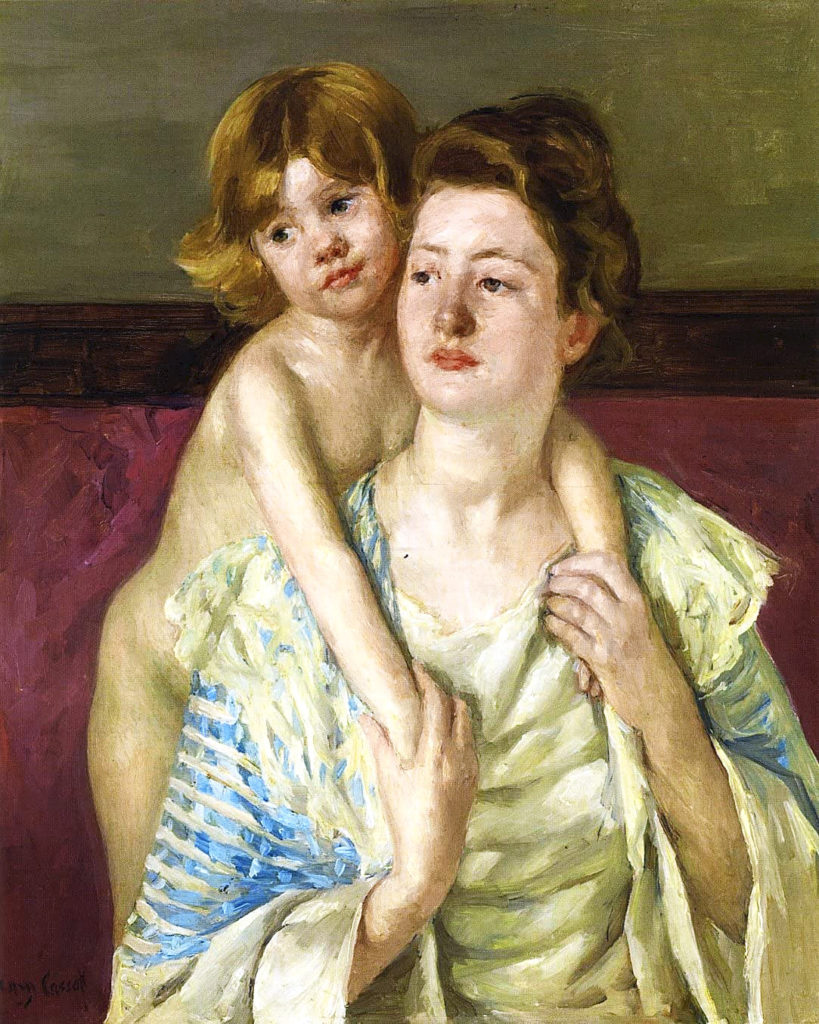

There are stunning paintings and prints on loan through the end of May — from Mary Cassatt’s “Antoinette Holding her Child by Both Hands” to Monet’s “Oat and Poppy Field,” “Honfleur, Fishing Boats” and “Boats Lying at Low Tide at Fécamp” to Honoré Daumier’s “La Salle des pas perdus au Palais de Justice.” And there is the opportunity to learn about many additional works, including those by Cassatt, Degas, Monet, Whistler, Pissarro, Renoir and Sisley, that were once in his possession.

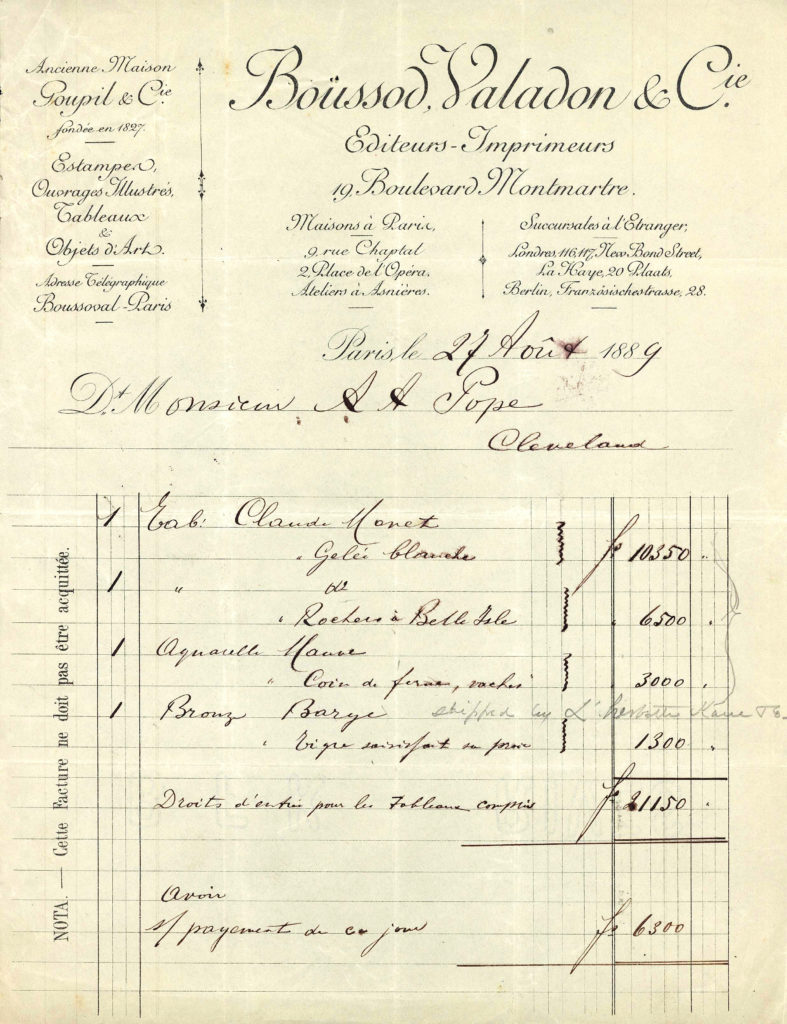

“When we began this exhibition research in earnest in the autumn of 2020, an extensive general listing was in place — that had been derived from household inventories, letters and receipts,” Swinbourne said. But there were paintings that staff still did not know about, or which they discovered had been incorrectly listed.

Ana N. Alvarez, Hill-Stead’s economic and curatorial assistant, was the point person for much of this, and she said that certain primary sources — namely purchase invoices and receipts — were not always definitive.

Receipt issued to Alfred Pope by Boussod, Valadon et Cie, Paris, August 27, 1889, for the purchase of “Rock Points at Belle-Ile” (1886) and “Grainstacks, White Frost Effect” (1889) by Claude Monet; “Farm Scene” (n.d.), by Anton Mauve; and “Panther with Slain Gazelle” (circa 1850), by Antoine-Louis Barye. Hill-Stead Museum Archives.

Hill-Stead reached out to the descendants of art dealer Paul Durand Ruel, who were able to provide a list of every item the dealer had either sold or bought back from Pope during his lifetime. Boussod, Valadon et Cie, and Knoedler Galleries, helped to fill in other provenance gaps. The Frick Art Reference Library and Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Watson Library proved valuable as secondary sources, and auction houses and commercial art galleries helped in the search for current owners.

In the end, “We were able to locate almost all the Impressionist artworks that were on our original list, with the exception of a Claude Monet pastel, a Berthe Morisot drawing and a Mary Cassatt drawing. Thus, we were able to track down the locations of 18 of 22 Impressionist works that had been dispersed as far away as Denmark, France and Japan.” The search continued right up until the opening day of the first phase of the exhibit, Alvarez added. In correcting a mislabeled work by Daumier, she tracked down its current owner. A loan agreement was signed, and the work arrived on the afternoon of the opening “and was installed just in time,” she said.

At the time when Pope began collecting, Impressionism was still very new and, to most people, Anne Higonnet, writes, in Hill-Stead, A Country Place, “frighteningly audacious.” Yet Pope, very much a progressive man of his time, grasped intuitively what the French Impressionists were saying about middle class Parisian society. During his 19 prime collecting years, he brought “an extraordinary eye” and “astonishing confidence.”

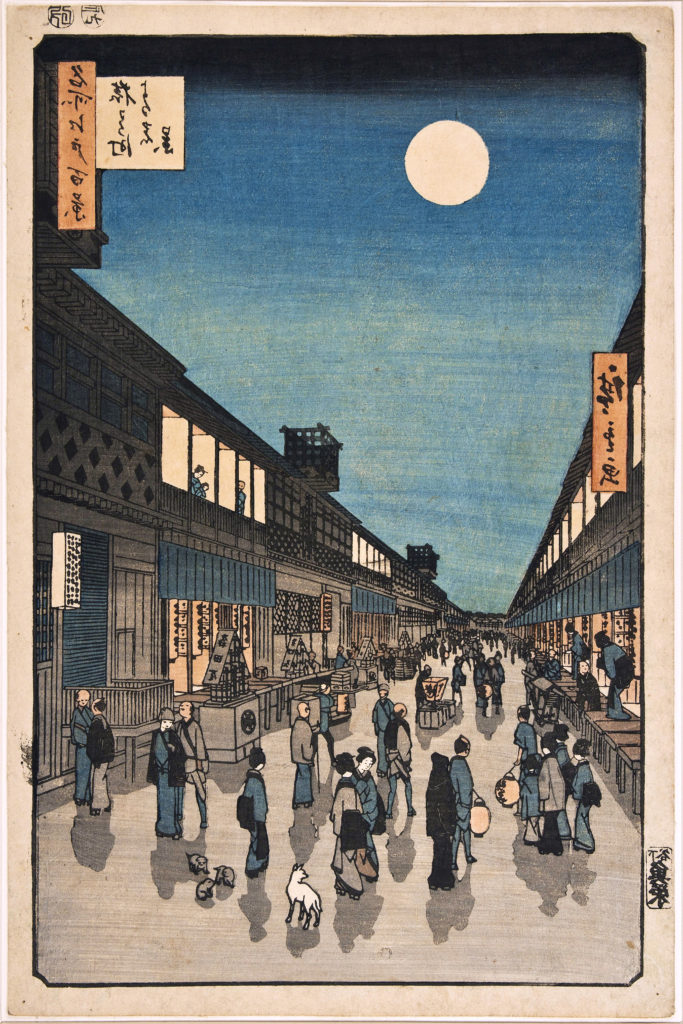

“Night View of Saruwaka Street” from “100 Famous Views of Edo” by Utagawa Hiroshige, 1856, woodblock print. Hill-Stead Museum.

“Unlike many of the American nouveaux riches who bought art in the late Nineteenth Century,” senior curator Melanie Bourbeau notes, in her essay “Alfred Atmore Pope: Generous Spirit, Discerning Eye,” that Pope “was not an avaricious collector concerned with cornering the market for a given commodity. Nor was he interested in artworks as moneymakers or status symbols. Like any good businessman he was wholly aware of the art market, and he knew who was collecting and what they were paying, but he did not see his own works as investments. Favoring quality over quantity he acquired only what was, to his mind, the very best, and he bought from the heart, not for financial gain,” she adds.

In his early years of collecting, between 1888 and 1893, he returned some 40 percent of the paintings to the dealers, including several Monets that he bought between 1890 and 1893, but by 1894, Bourbeau writes, he was more assured and cut his returns between 1894 and 1907 by about half.

“The paintings Pope collected were, above all, items he wanted to live with, enjoy to the fullest and share with his closest family and friends,” she said.

“Antoinette Holding Her Child by Both Hands” by Mary Cassatt, circa 1899. Private collection, United States.

Always a committed self-learner, he built an extensive art library, and relished intellectual discourse with dealers, artist friends James McNeill Whistler and Cassatt, and like-minded relatives and colleagues. But when it came to making decisions on acquisitions, Pope largely kept his own counsel. Bourbeau describes him as a fluid collector, who pruned his collection when he decided that he had bought a work that no longer resonated for him or encountered that he felt were of higher quality. His decision to exchange Whistler’s oil painting, “A Little Rose of Lyme Regis,” for “Carmen Rossi,” in just a day was an extreme example.

After encountering a wall of Japanese ukiyo-e prints on a visit to Monet at Giverny, Pope built his own collection with works by Katsushika Hokusai (1700-1849); Suzuki Harunobu (1724-1770), Kitagawa Utamaro (1750-1806) and Ando Hiroshige (1797-1858).

Over the course of his collecting years he purchased six works by Cassatt (four oils, one pastel, and one aquatint/dry point print), five by Edgar Degas, three by Edouard Manet, 11 by Monet (nine oils and two pastels); 25 by Whistler (seven oils and 18 etchings and lithographs) and one each by Morisot, Camille Pissarro, Pierre-Auguste Renoir and Sisley; works by Symbolist artists Eugène Carrière and Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, Hague School artists Jozef Israëls, Anton Mauve and the Maris brothers, Matthijs and Jacob; the realist Honoré Daumier; and post-Impressionists Étienne Tournes and Adolphe Monticelli. Pope’s works on paper outnumbered his paintings by about three to one, and his other valuable collections of mezzotint engravings and etchings. He collected an extraordinary cache of hundreds of material objects, as well.

Pope brought to his collections the same decisiveness and independence of spirit that characterized his highly successful business dealings, Bourbeau notes, but he was influenced in cumulative and indirect ways by a select few who helped guide his choices.

Drawing room, circa 1902-05. Left of the archway: “La Salle des pas-perdus au Palais de Justice” by Honoré Daumier (circa 1860). Right of the archway, left to right: “Jockeys” by Edgar Degas (circa 1886); “Fishing Boats at Sea” by Claude Monet (1868). Fireplace wall, left to right: “Rock Points at Belle-Ile” by Claude Monet (1886) “Grainstacks, White Frost Effect” (1889), both by Claude Monet; and “Girl with a Cat” by Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1882). Photo courtesy The Architectural Record.

In the evenings at Hill-Stead, Pope was known to single out favorite works and mount them on an easel in his library for contemplation. Against a white backdrop and under a bright spotlight, he would take great delight in the great works he had acquired individually.

Centerbrook Architects & Planners, who designed Hill-Stead’s award-winning new gallery, reproduced Hill-Stead’s original wallpaper and supplied several top-quality reproductions for the masterworks that could not travel.

Pope died in 1913 and in the ensuing years, his daughter sold off several significant paintings to underwrite costs of her own project, Avon Old Farms School, which she saw as a memorial to her parents.

“The choices made by Pope Riddle after her father’s death had obscured our understanding of artworks her father amassed,” Alvarez said, “but this new scholarship has elevated him for once and for all to a place among the leading collectors of his age.” Bourbeau agreed. “There is no doubt that future research will enhance his legacy, as scholars make discoveries that further expand the story of his art collecting journey.”

The second phase of the exhibition, the house display of major works, will open to the public on April 27.

Hill-Stead Museum is at 35 Mountain Road. For more information, www.hillstead.org or 860-677-4787.