Six portraits of members of the Levy-Franks family attributed to Gerardus Duyckinck I (1695–1746) are on loan from the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art. Photo Glenn Castellano, New-York Historical Society.

By Kate Eagen Johnson

NEW YORK CITY – “We need not tell our readers that the country is fast filling up with Jews; that from the newly gotten Santa Fe to the confines of New Brunswick, and from the Atlantic to the shores of the western sea, the wandering sons of Israel are seeking homes and freedom.” Rabbi Isaac Leeser made this observation in the October 1848 issue of his publication The Occident and American Jewish Advocate. While the implied numbers of Jewish American settlers may have been a bit optimistic on Leeser’s part, their geographical reach was not.

The exhibition “The First Jewish Americans: Freedom and Culture in the New World,” on view at the New-York Historical Society (NYHS) in Manhattan until March 12, demonstrates how Jews have lived and worked in Latin America, in the Caribbean and along the Eastern Seaboard from the start of European colonization. It also spells out the various ways they responded to the opportunities and challenges posed by the New World and the diverse identities they constructed as Jewish Americans.

“The First Jewish Americans” addresses the era from the late Sixteenth to the mid-Nineteenth Century and showcases more than 170 printed works, manuscripts, paintings and artifacts. It grew from “By Dawn’s Early Light: Jewish Contributions to American Culture from the Nation’s Founding to the Civil War,” an exhibition mounted in early 2016 by Princeton University Library. For the Princeton exhibition, curators drew from the library’s own holdings, particularly the Leonard L. Milberg Collection of Early Jewish Writers; the personal collection of Mr Milberg, Princeton Class of 1953; and the collections of other individuals and institutions.

Curator of decorative arts Debra Schmidt Bach, who served as the NYHS curatorial representative on the team that mounted “The First Jewish Americans,” explained its genesis. Upon seeing the Princeton exhibition, NYHS President and CEO Louise Mirrer recognized how the historical society could use this core of materials to craft a narrative about Jews coming to the New World, an understudied topic, while also adding pieces from its own and other collections as enhancements. Bach emphasized the decidedly collaborative nature of the project, stating that both the staff at Princeton University Library and Milberg were “completely on board with the idea” and that some scholars were involved with both exhibitions.

Curator of decorative arts Debra Schmidt Bach, who served as the NYHS curatorial representative on the team that mounted “The First Jewish Americans,” explained its genesis. Upon seeing the Princeton exhibition, NYHS President and CEO Louise Mirrer recognized how the historical society could use this core of materials to craft a narrative about Jews coming to the New World, an understudied topic, while also adding pieces from its own and other collections as enhancements. Bach emphasized the decidedly collaborative nature of the project, stating that both the staff at Princeton University Library and Milberg were “completely on board with the idea” and that some scholars were involved with both exhibitions.

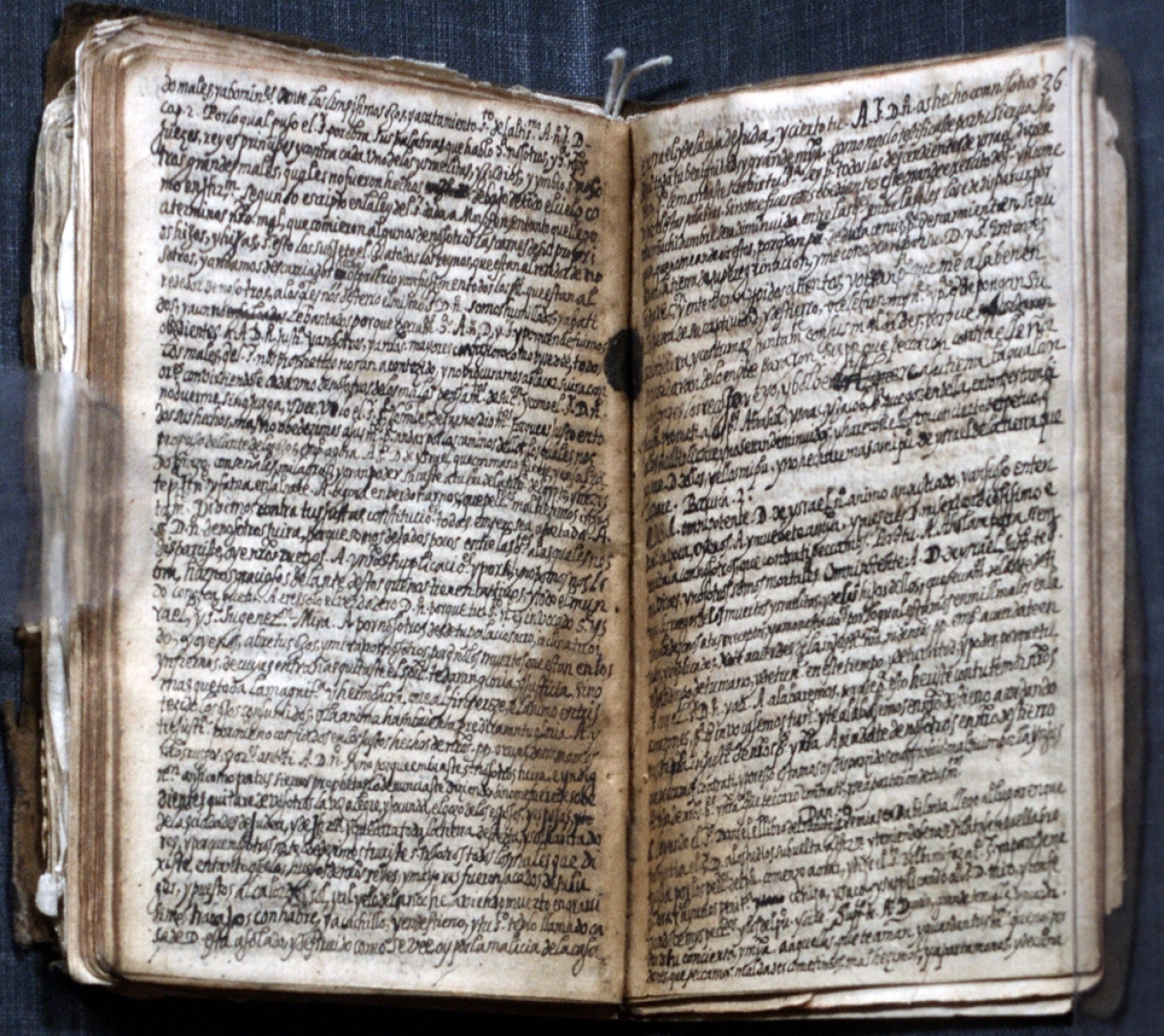

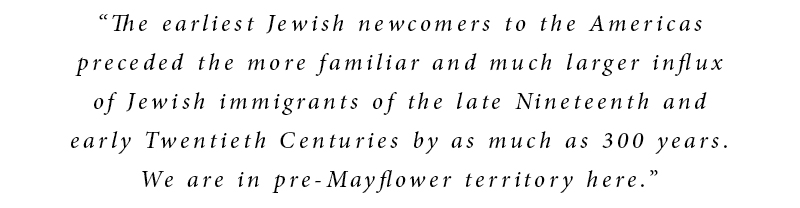

Bach related a revealing story about Leonard Milberg, whom she described as a “passionate and avid collector who is incredibly well informed” and the rediscovery of an archival treasure during the development stage of “The First Jewish Americans.” The “treasure” is a circa 1595 autobiographical document created by Luis de Carvajal the Younger, a “converso” Jew who was incarcerated, and later executed, during the Inquisition in Mexico. Milberg saw mention of it in a listing for a June 2016 auction in New York, which led him to reach out to scholars with specialties in Jewish and Latin American history.

It was determined that the document had been stolen from the Mexican National Archives during the 1930s and the manuscript was removed from the auction. Arrangements were made so that it could be exhibited in “The First Jewish Americans” before its return to Mexico. Summarized Bach, “it is a small document in actual size but extremely powerful in so many ways.” As an aside, the New York Times posted a fascinating account by Joseph Berger of the document’s disappearance and recent recovery to its website on January 1, 2017.

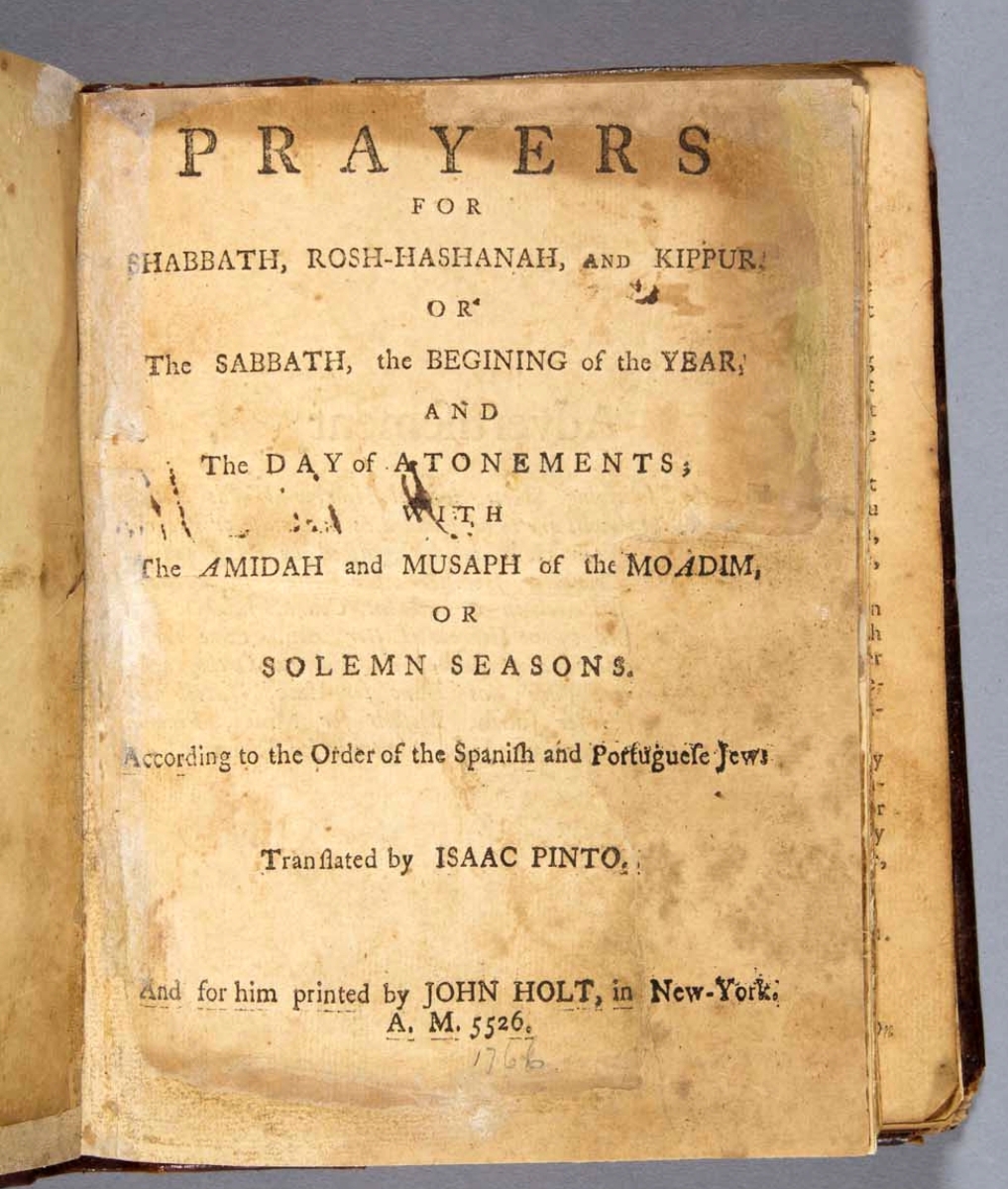

Through a special arrangement with the Mexican government, this recently recovered document is on view for the first time in “The First Jewish Americans.” Luis de Carvajal, a victim of the Inquisition in Mexico, was tried and burned at the stake in 1596. Memorias autobiographical manuscripts by Luis de Carvajal the Younger (circa 1567–1596) circa 1595, with devotional manuscripts. Manuscript leaves, three volumes, each stitched into plain wrappers. Courtesy of the Government of Mexico

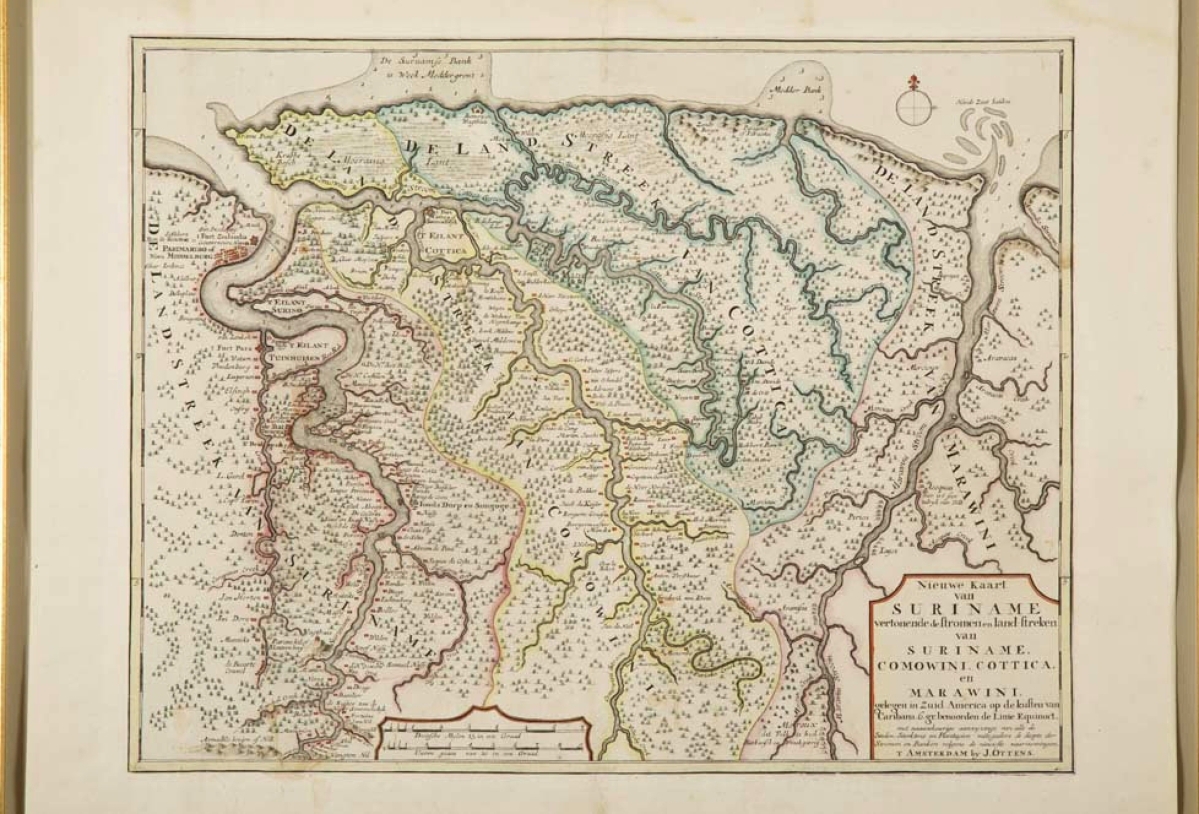

Asked about exhibition goals, Bach remarked, “We wanted to bring more recognition of Jewish history during the early years of settlement in the New World.” From the beginning of colonization, Jews who had been expelled from Spain, Portugal and elsewhere positioned themselves at ports and other locales throughout the Atlantic World, where they functioned as intermediaries in trade, communication and cultural exchange. Highlighted is the significant presence of Jews in the Caribbean during the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries, a little-known story. For example, exhibition visitors learn that the islands of Curacao, Suriname and Jamaica each contained more Jewish residents than the Thirteen Colonies as a whole until at least the middle of the Eighteenth Century.

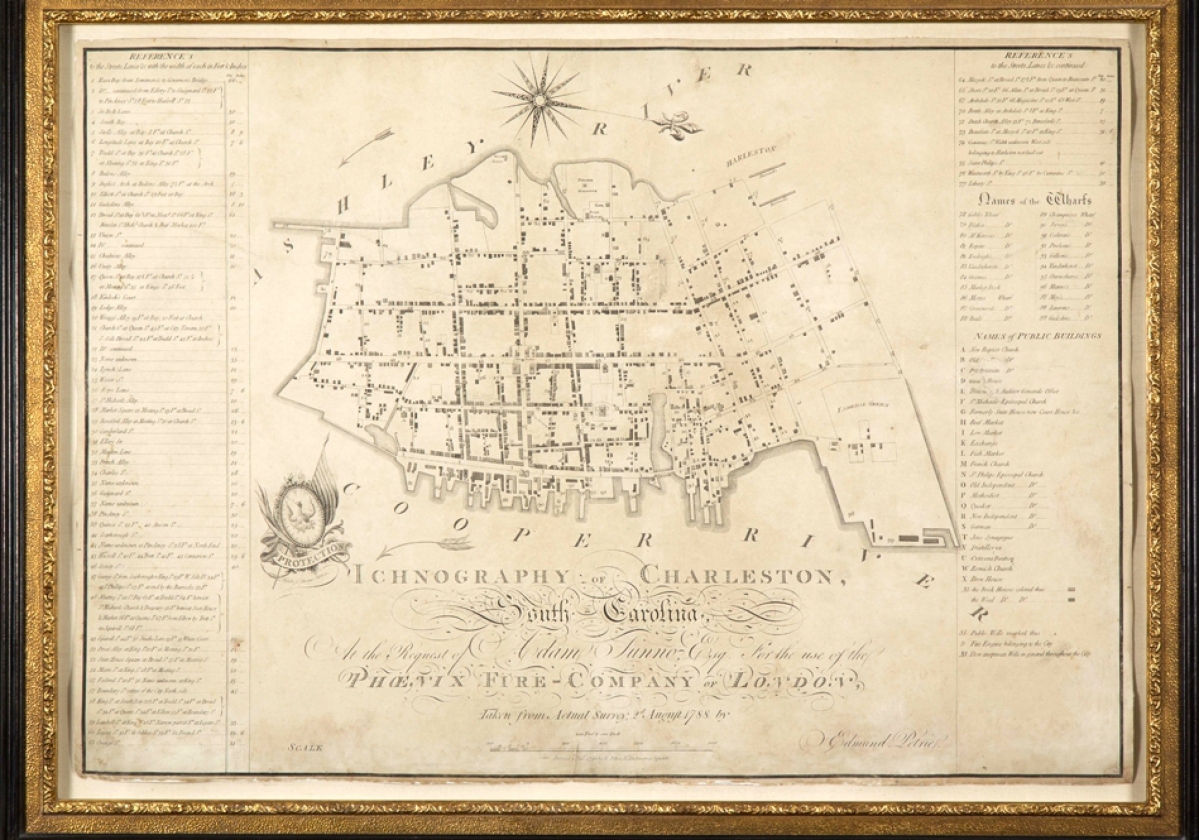

To represent the Jewish experience in the nascent United States, Bach and the exhibition team focused on individuals and organizations in Manhattan, Philadelphia and Charleston, S.C., the three cities with the largest Jewish populations during the early Nineteenth Century. It has been estimated that at the time the new nation formed, there were about 2,500 Jews in the United States.

Homing in for a minute on Manhattan, two boats carrying Jews landed in 1654, with the group of Jewish passengers aboard the St Catrina arriving from Recife, Brazil, despite opposition from New Netherland Governor Peter Stuyvesant. Bach explained how Shearith Israel, the first Jewish congregation in colonial North America, can trace its roots back to these 23 individuals. The prominent position Jews played in colonial New York mercantile and cultural life is illustrated in part by the impressive assemblage of six portraits of members of the Levy-Franks family dating circa 1735.

Explored primarily through documents are the activities of Jewish New Yorkers during the American Revolution, with many patriot Jews abandoning British-held Manhattan for the haven of Philadelphia either temporarily or permanently. Despite anti-Semitism and other hurdles, Jews in New York during the first half of the Nineteenth Century were active in the arenas of writing, publishing, business, education, music, theater and politics. By 1860, more Jews resided in New York than any other city in the United States.

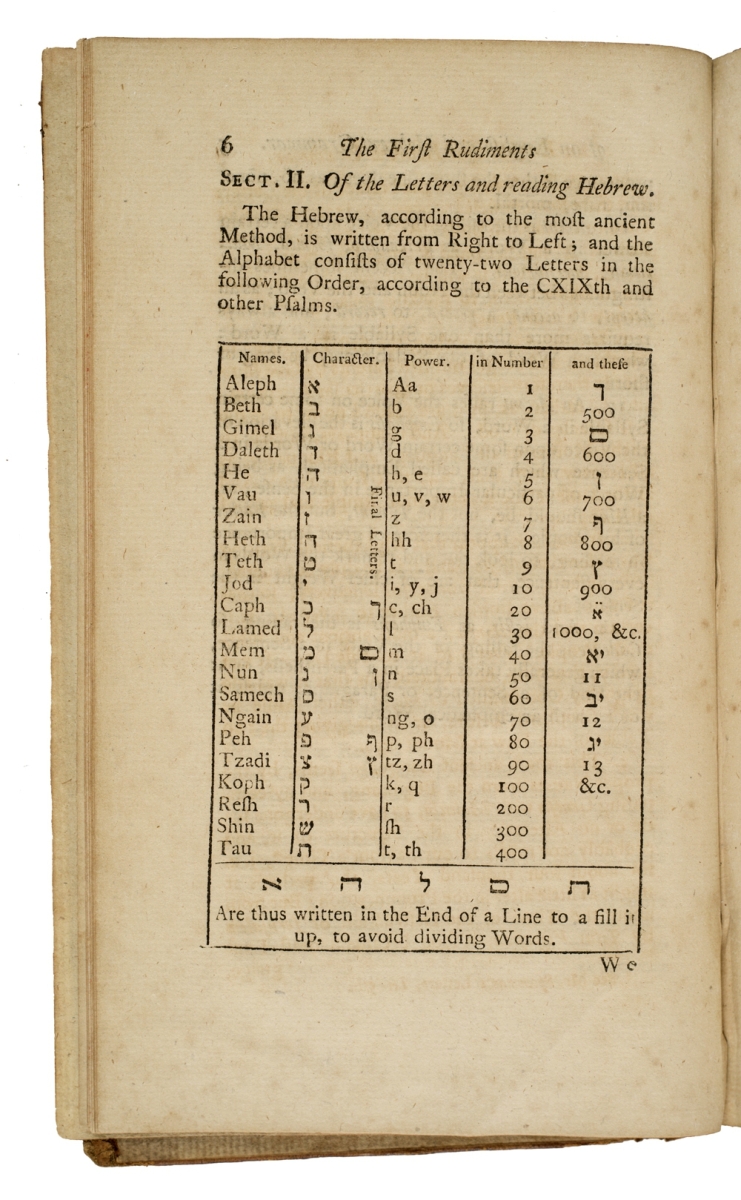

For an examination of a people for whom the Holy Word and literacy were paramount, it may come as no surprise that printed and penned documents form the bones and much of the flesh of the exhibition. Through texts in Hebrew and English and personal and institutional correspondence, Jewish writers posited ideas about, and reported on, religious and secular beliefs, attitudes and practices. Newspaper and magazine editors hosted dialogues among writers and readers, which spanned thousands of miles. A frequent topic was the clash between values and traditions developed over the centuries in Europe with the realities faced in the Americas. As an example, Jews who set up in isolated places noted difficulty in finding Jewish marriage partners and few, if any, opportunities for group worship.

Rebecca Gratz made history when she and other female members of Philadelphia’s Congregation Mikveh Israel founded the first Jewish lay charitable organization in the nation, the Female Hebrew Benevolent Society, in 1819 and the first Jewish Sunday School in 1838. Three oil portraits of Gratz by Thomas Sully are known. This oil on panel is from 1831. The Rosenbach Museum and Library

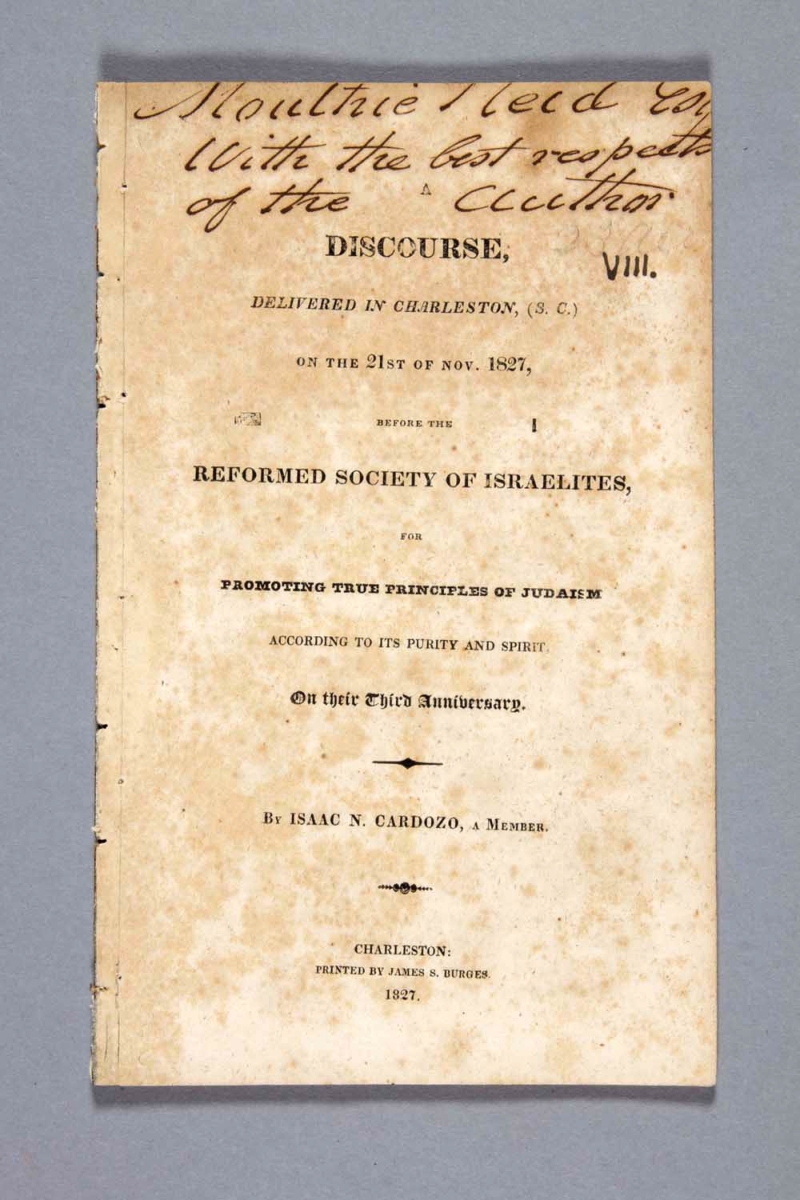

Similarly, non-Orthodox ideas, which were more in keeping with the dominant culture, sparked debate. Some of these new ways were first championed in the United States by the Reformed Society of Israelites for Promoting True Principles of Judaism According to its Purity and Spirit during the 1820s and included recitation of prayers in English as well as Hebrew, delivering sermons in English and playing music during services. (The group split from, but later rejoined, the Congregation Beth Elohim in Charleston, making it the birthplace of Reform Judaism in America.)

Other developments on the American scene included Jewish American women running charities and leading religious instruction for children as did their Protestant counterparts. Bach noted how each document on display leads to the consideration of larger issues and that “we can bring these voices alive through wonderful portraits.”

Among the Jewish Americans represented by likenesses are the artist, daguerreotypist and Western adventurer Solomon Nunes Carvalho; the painter Theodore Sidney Moïse; the philanthropist and religious educator Rebecca Gratz; the first Jewish commodore in the United States Navy and savior of Monticello Uriah Phillips Levy and the multifaceted visionary Mordecai Manuel Noah, who attempted to establish a city of refuge for Jews from around the world on Grand Island near Buffalo.

Then as now, Jewish American identity was not monolithic. Individuals’ biographies make obvious its ethnic, cultural and religious dimensions. Some openly identified as Jews and were religiously observant. Others did not and/or were not. Some accepted or assumed roles and affiliations as young persons, which they later gently or strongly rejected. Generally viewed as outsiders by Christian America, Jewish Americans dealt with cultural and religious retention, assimilation, accommodation, prejudice and persecution variously.

There were also those who were shaped by Judaism and the Hebrew language, but were not Jewish themselves. Falling into this category is “Man of the Hour” Alexander Hamilton, whose stepfather was Jewish, who attended a Jewish school on Nevis and who fostered close connections with the Jewish community throughout his life. In a different but related mode, NYHS founder John Pintard and other early American collegians studied Hebrew as a classical language, the underlying thought being that Christians could better understand the Old Testament if they could read it in Hebrew. Out farther on that branch are the American linguists and others who thought Native Americans could be among the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel, a theory, proposed in the Seventeenth Century, that enjoyed currency into the Nineteenth Century.

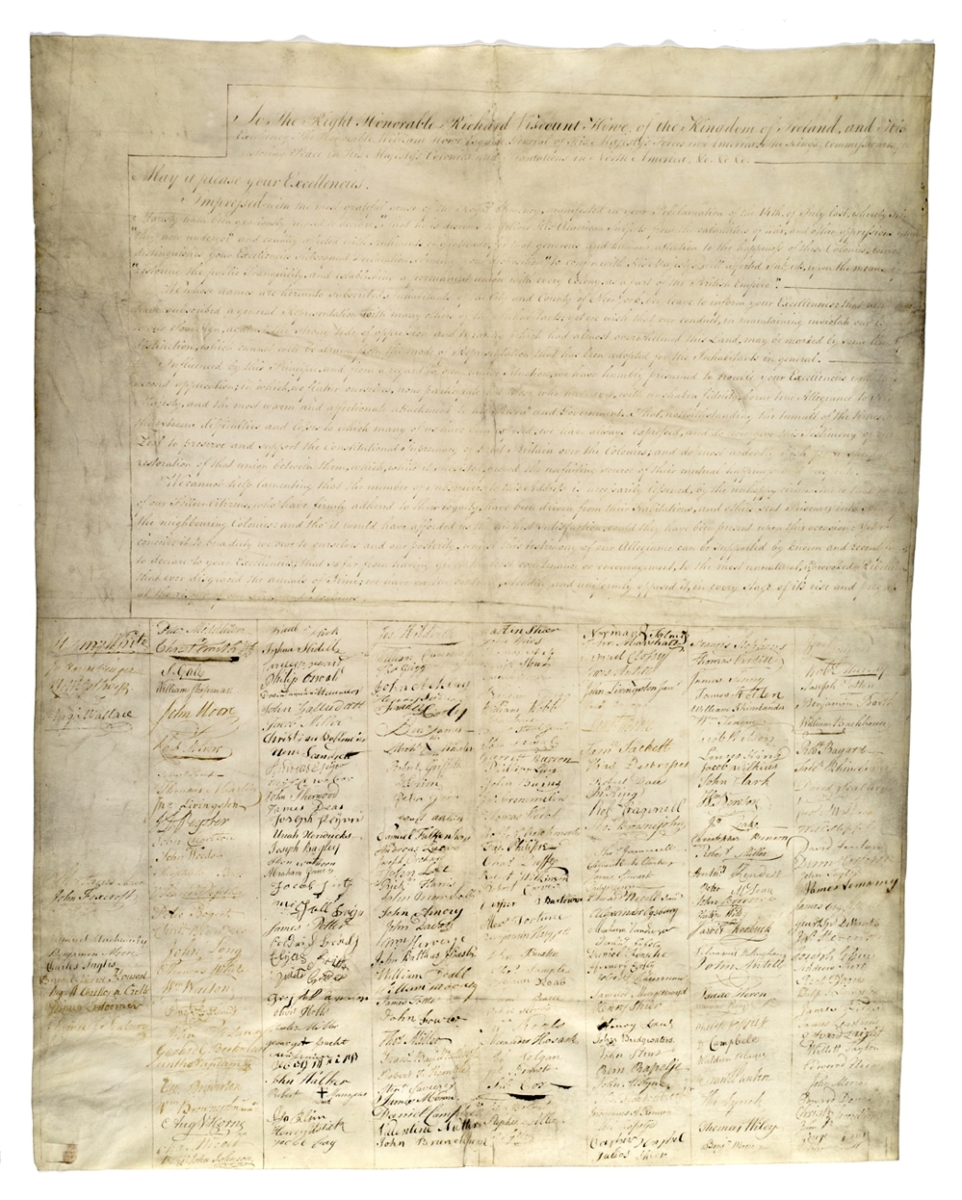

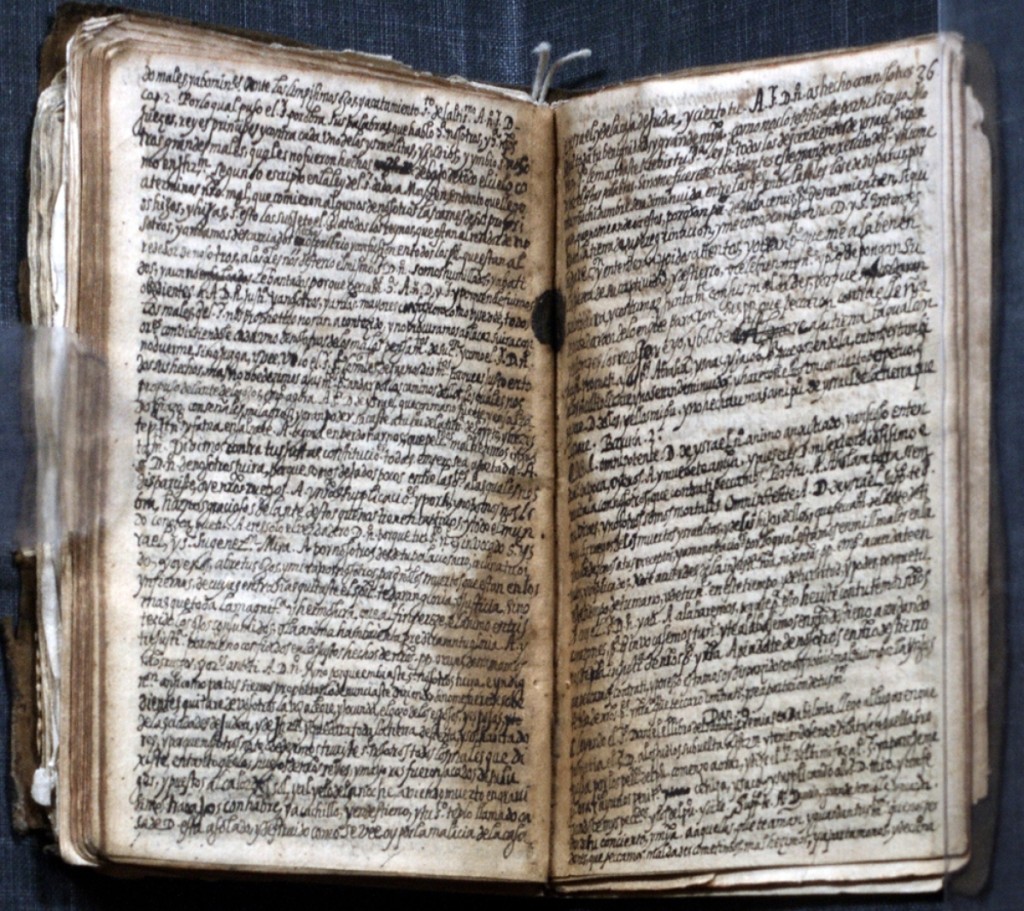

This declaration of loyalty to the British throne contains 932 names. Abraham Gomez, Uriah Hendricks and Moses Gomez Jr were among the 16 Jews who signed the document. “Address of Loyalty to the Conquerors, Admiral Richard Howe and General William Howe,” New York, October 16, 1776. New-York Historical Society Library

For those interested in learning more, Debra Schmidt Bach recommended two resources. The John L. Loeb Jr Database of Early Jewish American Portraits is hosted online by the American Jewish Historical Society at www.loebjewishportraits.com. Containing more than 400 paintings, drawings, miniatures, photographs and silhouettes, the database can also be accessed in the NYHS exhibition galleries. Produced by Princeton University Library in 2016, By Dawn’s Early Light: Jewish Contributions to American Culture from the Nation’s Founding to the Civil War contains 13 essays by leading scholars and a detailed listing of the art, artifacts and documents displayed in the companion exhibition. Many of the works are also on view in The First Jewish Americans. This volume can be purchased at the NYHS Shop and online.

There is much to amaze even the most avid students of the American story here. The earliest Jewish newcomers to the Americas preceded the more familiar and much larger influx of Jewish immigrants of the late Nineteenth and early Twentieth Centuries by as much as 300 years. We are in pre-Mayflower territory here. The personas and lifestyles they adopted were remarkably diverse and the impact they made outsized considering their small numbers. Leonard Milberg, Princeton University Library, New-York Historical Society and their private and institutional partners are to be thanked for preserving, documenting and publicly sharing items central to this underappreciated aspect of American history.

The New-York Historical Society is at 170 Central Park West. For more information, 212-873-3400 or www.nyhistory.org.

Kate Eagen Johnson is an expert in American decorative arts and an independent museum consultant, historian, lecturer and author.