By Laura Beach

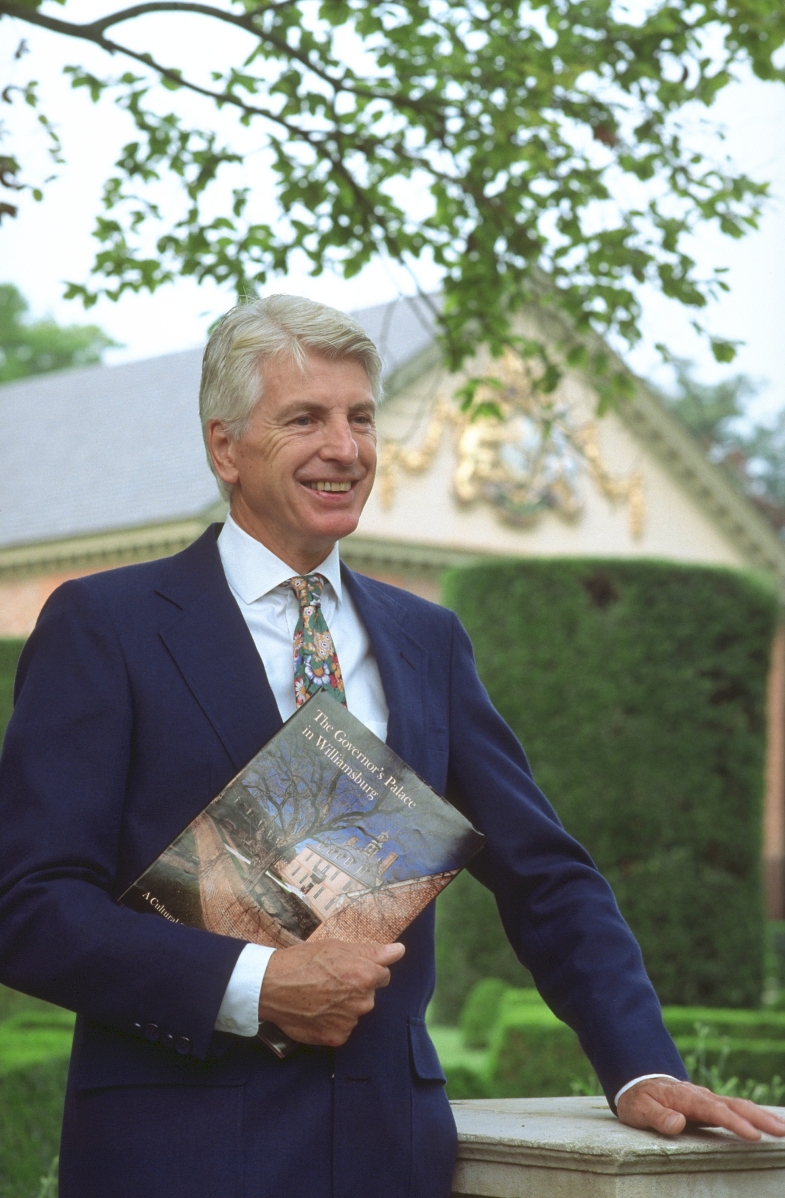

WILLIAMSBURG, VA. – J. Thomas Savage, called Tom, says he was an odd child, which makes him more or less ordinary among his antiquarian peers. “I was a kid who liked old houses and still do,” says the decorative arts historian, who recently left Winterthur after 16 years to return to his first love, Colonial Williamsburg (CWF), where he serves as the Foundation’s director of educational travel and conferences.

The position could not better suit Savage’s talents if it were designed with him in mind, which one suspects it was. Since bursting upon the curatorial stage at Historic Charleston Foundation in 1981, Savage has demonstrated an unsurpassed ability to captivate audiences. A compelling speaker and entertaining guide, he wears his erudition lightly. Only one so besotted with the field could find so much about it to amuse.

“I have marveled at his ability to relate to virtually any audience, to promote Winterthur nationally and internationally, and to articulate the minutest details about history and the decorative arts in an entertaining and engaging way,” Winterthur’s interim chief executive officer Chris Strand wrote in May of the museum’s departing director of external affairs.

_(002).jpg)

With Margaret Pritchard at Cottesbrooke Hall in Northamptonshire. “Tom has an amazing aesthetic sense and tremendous wit and charm. His depth of knowledge allows him to engage people on many topics,” says Colonial Williamsburg’s deputy chief curator.

Savage’s extravagant sociability and gift for friendship prompt one to ask which he prefers, people or houses? “I particularly like it when good people happen to good houses. I hate it when bad people happen to good houses. Then I root for the houses,” he says.

The curator’s favorite historic structures provide a rough guide to his identity. Initially there was Eyre Hall. A “conscious combination of architectural sophistication and regional preference,” as he has described it, the circa 1760 country seat on Virginia’s Eastern Shore was a youthful infatuation for Savage, who grew up nearby, the son of a building contractor with deep roots in the region and a classically trained musician from Pennsylvania who imparted her love of music to her son.

“What’s remarkable but completely typical is that even as a very young person, Tom got to know Eyre Hall’s owners, descendants of the original family who lived there. They’ve become good friends of his and mine,” says Margaret B. Pritchard, deputy chief curator at Colonial Williamsburg, who met Savage soon after arriving at Colonial Williamsburg to work on the Governor’s Palace project in 1978 and has been close to him ever since.

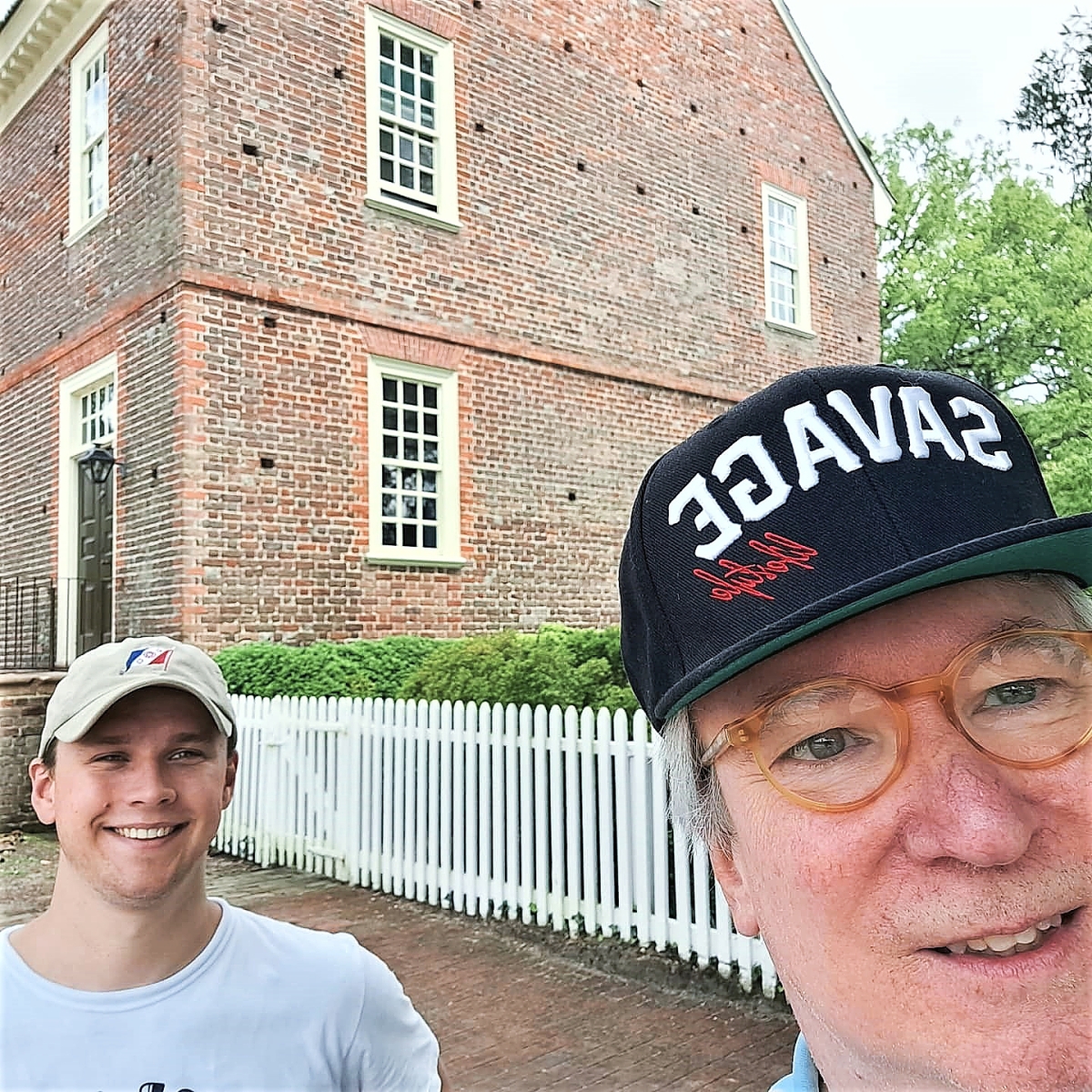

_(002).jpg)

Savage worked as a costumed interpreter at Colonial Williamsburg during his undergraduate years at the College of William and Mary. This photograph was taken in 1976 at CWF’s Wythe House.

Other cherished properties, all dating from the mid-Eighteenth Century, are Charleston’s Miles Brewton House, restored between 1988 and 1992 by Savage’s friends Peter and Patricia Manigault. He admires Westover for its “bookishness” and long association with the Byrd family. As he explains, “Westover is the iconic Virginia Georgian house that has been gently lived in and well documented, but not overly restored. I like houses to have some seasoning. You want to feel the past.”

Topping Savage’s list is Mawley Hall, a Georgian country house in Shropshire, England. “Baroque, of course, but I understand it better as an Italianate villa in England,” says the historian, who knew it from Clifford Musgrave’s 1972 “Living with Antiques” piece in The Magazine Antiques long before he visited it a dozen times and got to know its owners, the Galliers-Pratt family.

Savage grew up in the tiny enclave of Belle Haven – current population 500, of which he suspects a few of the counted are “dogs, cats and horses” – a little over two hours north of Williamsburg, Va., even as a boy his favorite birthday destination. “My father’s family has been on the Eastern Shore since the Seventeenth Century. I come from a long line of dirt farmers, so no delusions. I am not a professional Virginian, which I find a bit boring and increasingly irrelevant,” he says.

He was nonetheless deeply affected by his surroundings, noting, “The Eighteenth Century was never far away in rural Virginia. The lifestyle, the foodways, the agricultural and fishing aspects that had been such a mainstay of the culture. For me it was the antiques, architecture, gardens and interiors.”

.jpg)

Mawley Hall in Shropshire, England, is Savage’s favorite house. “Baroque, of course, but I understand it better as an Italianate villa in England,” he says.

At 14, the budding museum professional enrolled in St Andrew’s School, a stone’s throw from the Historic Houses of Odessa, then administered by Winterthur Museum. A sympathetic faculty member who shared his interests ferried him to antiques shows, house tours and to his weekend gig as a volunteer guide at Odessa.

Savage began his undergraduate studies in 1975 at the College of William and Mary, whose campus abuts Colonial Williamsburg’s. By the end of his freshman year, he was working as a costumed interpreter at the history museum. A junior-year seminar co-taught by faculty and Colonial Williamsburg curators began his introduction to some of the field’s great talents, among them Graham Hood, John Austin, John Davis, Wallace Gusler, Mildred Lanier, Joan Dolmetsch, Leroy Graves, Linda Baumgarten, Ivor Noel-Hume, Paul Buchanan and Savage’s near contemporaries, Sumpter Priddy and Brock Jobe.

He met Ronald L. Hurst, to whom he now reports, in 1978 at the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts’ Summer Institute. “We’ve been friends for 43 years,” says CWF’s chief curator and vice president for museums, preservation and historic resources. “We were the only two undergraduate students in the program and found we were kindred spirits, true object nerds who sat up until 1 am reading probate inventories.”

.jpg)

“Tom has opened my eyes to the subtlety of English architecture. Once he took me to Badminton for a private visit with the Duchess of Beaufort. It’s just not something the average person does,” Margaret Pritchard says. Savage, left, is seen here at Badminton, Gloucestershire, with the late Duke of Beaufort.

Diploma in hand from the Cooperstown Graduate Program in museum studies, Savage landed at Historic Charleston Foundation, where, following an internship, he was named the foundation’s first professionally trained curator and director of museums. In Charleston, Savage refined his signature take on American art and design, a stance in part shaped by wide travel and a scholarly familiarity with the Southern plantocracy, deepened through projects such as the 1999 exhibition and book In Pursuit of Refinement: Charlestonians Abroad, 1740-1860, to which he contributed. As he explains, “I see American art as a synthesis of all sorts of experience. I am an Americanist who looks at America through a European lens.”

“Tom has been the go-to guy on many topics,” Hurst says of the man who came to be known as “Mr Charleston.” “When I needed someone to write the essay on Charleston material culture for Southern Furniture 1680-1830: The Colonial Williamsburg Collection, the 1997 book I did with Jon Prown, I went to Tom.”

Savage became friendly with formative figures in Charleston’s preservation movement, which flourished in the 1920s. “Many of the pioneers were still in their houses. That was exciting in itself. Mrs Henry P. Staats, for instance, lived in the Thomas Rose House, an iconic Charleston structure. I was a guest for her rather frequent black-tie dinners, as well as at Gertrude Sanford Legendre’s gatherings at Medway, where the gentleman engaging you in conversation might be the Duke of Wellington. It was part of a Charleston that no longer exists.”

.jpg)

Lady Clifford of Chudleigh, left, arranged for Savage to meet Downton Abbey’s creator, Julian Fellowes. The introduction smoothed the way for Winterthur Museum’s blockbuster 2014 exhibition “The Costumes of Downton Abbey.” Of the eye-catching jacket, Patrick Baty says, “Tom is never one to take himself too seriously and has been known to wear what he calls his ‘travel mistake’ at smart dinners — here a German ‘trachten’ jacket made of scarlet suede with silver buttons. So elegant and very envy-making, although I fear that I would never be able to carry it off with as much insouciance.”

Savage decamped for Sotheby’s in 1998, where he directed the New York branch of its Institute of Art and led its American Arts Course. “I remember asking then CEO Dede Brooks if people would be put off by my Southern accent. ‘Oh, no,’ she said, ‘They’ll eat you up with a spoon.'” The position, which Savage held until 2005, sharpened his teaching skills and cemented friendships with colleagues such as Wendell Garrett, whom he had long admired.

Like Garrett and Graham Hood, both gifted orators, Savage has become an ambassador for historic design, a spokesman whose passion for his subject, eye for colorful detail and lively wit make the esoteric accessible. He acknowledges the influence of both men, speaking with admiration of Hood’s interdisciplinary approach to the study of objects and Garrett’s encouragement of young scholars, but says his own prowess has less to do with verve than with careful preparation.

By way of illustration, he recalls his first lecture to the Colonial Williamsburg Antiques Forum in 1987. “The night before it I was awake with nerves. When the fire alarm accidentally went off in the wee hours at the Williamsburg Inn, where I was staying, I jumped to my feet and began reciting my lecture. I later recounted the story for my audience, adding, ‘I hope you will all join me in the relief that the second time I give my lecture today, I give it with my clothes on.’ Ron, who followed me at the lectern, began by saying, ‘What Tom doesn’t know is I pulled the fire alarm!’ It was just one instance of our camaraderie over the years.”

Savage is now bringing his knack for judging listeners to CWF’s portfolio of conferences, its 72-year-old Antiques Forum chief among them. Long led by Hurst and Pritchard, and more recently steered by Angelika Kuettner and Neal Hurst, the forum is a collaborative enterprise that, while down in attendance from its peak years, still draws roughly 350 participants annually.

.jpg)

Savage, center, is flanked by HRH Prince Charles and gardens authority and television host P. Allen Smith at a dinner at Buckingham Palace. The event was in support of the Royal Oak Foundation’s Campaign for Knole.

“The forum has evolved into a contemporary model that is far more dedicated to advancing scholarship and experience in a wider and more inclusive demographic. Lectures by young scholars, something you would not have seen here in the 1950s, are now one of its most thrilling features,” says Savage, who plans to build on the forum’s strengths.

Armed with some of the best international contacts in the field, Savage is also resurrecting Colonial Williamsburg’s travel programs, an initiative of interest to the institution’s new president and CEO, Cliff Fleet. Savage has been leading groups abroad since his Charleston days and did so most recently at Winterthur. His interest in the British country house blossomed in 1980 when he first attended the Attingham Summer School. He developed an affectionate bond with the program’s late director, Helena Hayward, a furniture authority, author of several books and the spirited voice of the Antiques‘ “Letter from London” column in the 1950s.

“You might have come to Attingham primarily interested in Humphry Repton landscapes, but you left having this amazing exposure to all aspects of the British country house. It was an immersion experience in such a variety of topics that I can’t think about the decorative arts field in anything other than a holistic way, because that’s really the way I was taught,” Savage notes.

Writer Franz Lidz captured Savage’s mastery of country-house diplomacy for the 2011 Wall Street Journal feature “Upstairs, Downstairs and In Between,” writing, “For more than 20 years, Savage has been hooking up connoisseurs of the decorative arts with the owners of England’s great estates, where most of the finest antiques are to be found.”

.jpg)

“A favorite place,” Savage says of the Sedlec Ossuary, a small chapel in the Czech Republic. “It makes some people quite uneasy, but I can’t think of anything lovelier than spending eternity as a bone chandelier, obelisk or trophy arrangement.”

“Tom probably has a greater knowledge of British houses than most native Brits and seems to know most of the owners, as well. One might say that he is very well-connected. He is a dedicated Anglophile and, I sometimes think, would make a wonderful US ambassador over here,” says Patrick Baty, the eminent British paint historian and author of The Anatomy of Colour.

Alliances nurtured by travel bore fruit when Savage’s friend Lady Clifford of Chudleigh introduced him to Julian Fellowes, a peer of the House of Lords and creator of the television series Downton Abbey. Savage recalls that when they did finally meet, Fellowes remarked, “Oh, Tom, I’m so sick of hearing about you. Of course, Winterthur can use the Downton Abbey name.” Fellowes’ blessing contributed to the success of Winterthur’s blockbuster exhibition “The Costumes of Downton Abbey,” staged at the height of Downton mania in 2014.

“Winterthur colleagues Maggie Lidz, Linda Eaton, Tom and I enjoyed working on so many projects together and trying to preserve the legacy of H.F. du Pont, both as a collector and designer. Working with Chris Strand, we extended that into the garden and the estate and brought so much together,” Winterthur estate historian Jeff Groff said in a recent farewell tribute to his co-worker.

Savage is an ardent, if occasionally mystified, plantsman – “My garden never looks like the pictures that inspire me, but boxwood is a Virginian’s basic need” – as well as a collector of Chinese export porcelain, some of it armorial, and plain English furniture that would have been at home in Eighteenth Century Virginia or South Carolina. Pritchard, formerly CWF’s curator of maps, prints and wallpaper, inspired her friend’s love of 1760s “fanciful heads” by Thomas Frye, whom she regards as perhaps the best English mezzotint engraver to master the technique.

_(002).jpg)

Savage and interior decorator Thomas Jayne with Helena Hayward, director of the Attingham Summer School. “She was a major tutor, mentor, influence and the dearest of friends. I still miss her,” Savage says of Hayward, who died in 1997.

Recently uprooted from the 1920s Cotswold-style cottage in Wilmington’s Wawaset Park neighborhood, where he lived for 16 years, Savage is settling into the Palmer House on Williamsburg’s Duke of Gloucester Street.

“Tom will just love living in the historic area and fixing the house up. I haven’t heard him this excited in a while,” says Pritchard. Savage confides, “I’m sort of living my 12-year-old self’s dream. I’m hoping to return the Palmer House interior to some semblance of its Eighteenth Century appearance. Colonial Williamsburg has kindly repainted the dining room and parlor closet the pearl gray revealed in scientific paint analysis.”

The late British scholar Geoffrey Beard, purportedly quoting Helena Hayward, is said to have described the American Friends of Attingham as “a remarkable group whose members, having once met, throw a party, constantly visit each other, recruit new young students for the course, act as an employment agency and arrange each other’s careers.” Much the same might be said of the overlapping spheres in which Savage has made himself indispensable.

“I’ll be 65 this year. I entered the field as a guide in my teenage years. I’ve never been more encouraged by what I see. Absolutely brilliant minds are emerging from the leading programs. They are asking vastly different questions than we were taught to ask, and they are the right questions. I have learned at least as much as I’ve taught.”

_(002).jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)