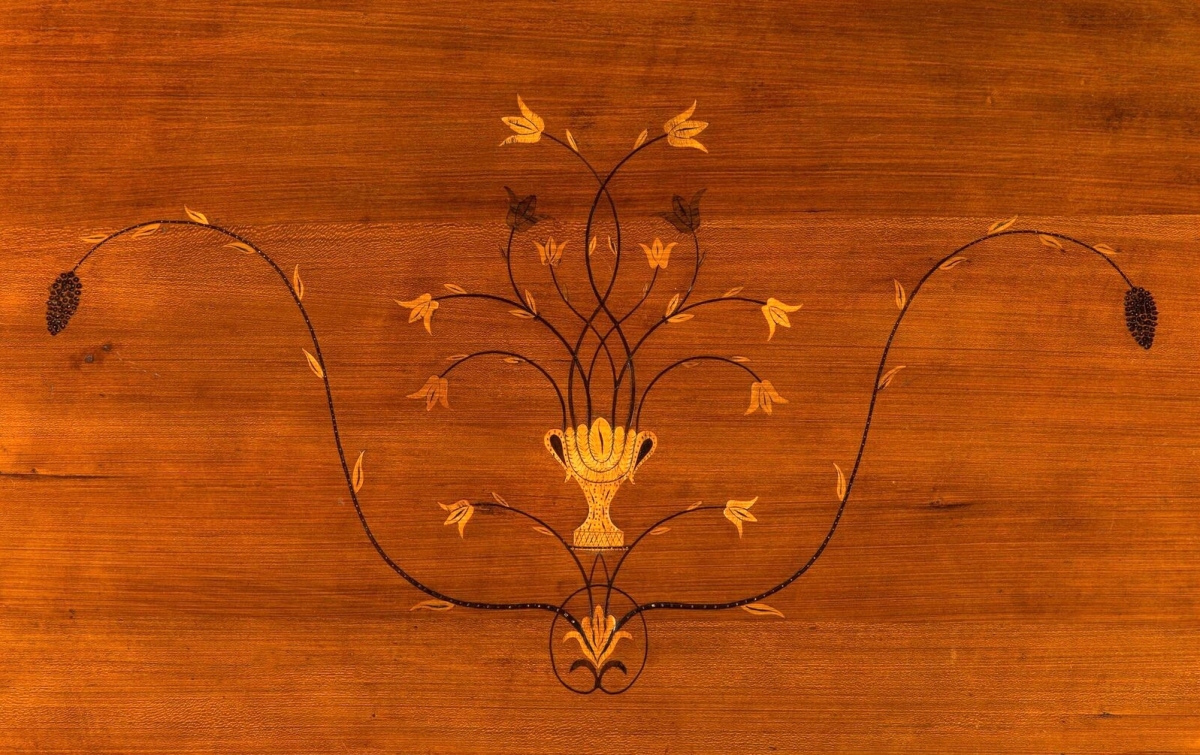

Serpentine chest of drawers by Nathan Lumbard. Inscribed “Made by Nathan Lumbard Apl 20th 1800.” Cherry, cherry and mahogany veneers, light and dark wood inlays, white pine; height 37 by width 41-3/8 by depth 21¾ inches. Private collection. —Gavin Ashworth photo (Image 1)

By Clark Pearce

ESSEX, MASS. – The intense study of the furniture of Nathan Lumbard (1777-1847) began in 1987 with a serendipitous discovery. I was in a dealer’s shop, examining a lovely inlaid serpentine chest [image 1] when I noticed the glint of a graphite inscription on the case bottom. Though faint, I was able to decipher “Made by Nathan Lumbard, Apl 20th 1800,” and a second line that reads “Repaired by Enoch Pond March 21st 1837.” Because of the chest’s resemblance to the lower case of the sublime desk and bookcase at Winterthur Museum, I called Brock Jobe, then chief curator at the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities. He saw the similarity instantly [image 2].

We also recognized the potential importance of this inscription and commenced a careful study of both pieces. Though less elaborate, the chest shares many features with the desk and bookcase. The drawer fronts on both have vertically grained cherry veneer, mahogany banding set on a 45-degree angle, chevron stringing and straight bracket feet that follow the same template. Within the cases, the two pieces display the same neat, meticulous workmanship and virtually identical drawer construction. There was no question that Nathan Lumbard had played a major role in the construction of the two objects.

Then, in its December 1991 issue, The Magazine Antiques published a study by William Short that tied the desk and bookcase to a group of other furniture with strong histories of ownership in central Massachusetts, but without any attribution to a maker. Armed with the knowledge of the maker of the inscribed serpentine chest, the larger group identified by Short provided a critical mass of pieces that propelled us into an in-depth study that culminated seven years later in an article in the Chipstone Foundation journal American Furniture 1998 titled “Sophistication in Rural Massachusetts: The Inlaid Cherry Furniture of Nathan Lumbard.” In that article, we were able to add Lumbard’s name to many pieces in the burgeoning group, and some knowledge of the man and his history.

In 2013, as part of the Four Centuries of Massachusetts Furniture project, Christie Jackson, then curator at Old Sturbridge Village, breathed new life into the study of Lumbard’s furniture by mounting an exhibition, “Delightfully Designed: The Furniture and Life of Nathan Lumbard.” Jackson’s skills in primary research brought forth all kinds of new information, such as the likelihood that Sturbridge cabinetmaker Oliver Wight (1765-1837) took Lumbard as an apprentice in the mid-1790s, and the discovery of a tall clock inscribed by Wight, dated 1791 [image 3]. She found accounts kept by neighbors that documented the cabinetmaker’s activities in Sturbridge and later in Sutton.

But Jackson also brought Lumbard to life with far more than furniture. She was able to track down personal possessions that had belonged to Lumbard’s relatives and clients, reinforcing the web of connections that existed within a rural community. Combining our passion for Lumbard’s work and wanting to create a permanent record of our findings, Jackson, Jobe and I came together to write a book, setting off a new round of research and a renewed search for new objects.

But Jackson also brought Lumbard to life with far more than furniture. She was able to track down personal possessions that had belonged to Lumbard’s relatives and clients, reinforcing the web of connections that existed within a rural community. Combining our passion for Lumbard’s work and wanting to create a permanent record of our findings, Jackson, Jobe and I came together to write a book, setting off a new round of research and a renewed search for new objects.

Among the takeaways from the new research is that Nathan Lumbard was a true New England original. The “language” of his Neoclassical inlays are delightfully inventive and exuberant. His pierced pediments and carved details are unusual and inspiring. The forms of his furniture are bold and often unexpected. All that said, it is important to understand the context in which he made these extraordinary objects and the contribution of others upon which Lumbard built his success.

Around 1790, there was a major shift afoot in cabinet shops across greater Worcester County. Printed British pattern books like George Hepplewhite’s Cabinet-Maker and Upholsterer’s Guide carried many new design ideas deep into the agrarian hinterlands. A new generation of young, ambitious artisans embraced the Neoclassical style, changing forever the way the region’s cabinetmakers went about their business. By the late 1790s, cabinetmakers all over central Massachusetts were making furniture in the Neoclassical style with inlaid decoration. Among the well-known makers who took up the new style were Erastus Grant (1774-1865) of Westfield, William Lloyd (1779-1845) of Springfield and Alden Spooner (1784-1877) of Petersham and Athol. Neoclassical forms with inlaid decoration were in the very air that Lumbard breathed during his apprenticeship.

An important element that set the stage for Lumbard’s work was Oliver Wight, his presumed master. Exactly how Wight was exposed to the Neoclassical style remains unclear, but the furniture attributed to him plainly shows that he was an early adopter, especially in the second half of the 1790s. Compare the fire screen attributed to him with the one that descended in Lumbard’s family [images 4 and 5], or the serpentine chest possibly by Wight compared to a similar chest with inlaid drawer fronts that is attributed to Lumbard [images 6 and 7]. These comparisons demonstrate that Wight was the trailblazer who embraced the language of Neoclassicism before passing the torch to Lumbard, his apprentice, who went on to refine and perfect it. The true genius of Lumbard is his superior craftsmanship, love of complex inlay and impeccable sense of design and proportion. In these areas, he surpassed his master.

Desk and bookcase attributed to Nathan Lumbard, 1798–1802. Cherry, mahogany banding, light and dark wood inlay, basswood, white pine; height 92½ by width 42½ by depth 21-3/8 inches. Winterthur Museum. —Laszlo Bodo photo (Image 2)

On the inside backboard of a fully inlaid tall clock case, Lumbard wrote “Top / December 9th 1801 / N. Lumbard / Maker” [image 8]. The signed case documents a rich vocabulary of veneering and inlay motifs also seen on other pieces that can be attributed to Lumbard. Typical of his inlay are the light and dark swirling paterae that are framed by diamonds of solid banding or chevron stringing, and the delicate stems with leaves and flowers emanating from a cup or urn. One of his most remarkable inlays is a complex arabesque set into the top of a serpentine chest [image 9]. The familiar two-handled urn holds multiple stems of flowers and leaves that cross one another to form Gothic window mullions. Below are a pair of arching stems supporting alternating leaves with single berries at the terminals. The stems in Lumbard’s inlays are actually carefully tapered, thinning as they extend outward. The thicker sections of the stems are inlaid with tiny white squares that catch the eye and give them a sparkly aspect. These labor-intensive and elaborate inlays put Lumbard’s work far above his regional competitors.

No review of Lumbard’s work would be complete without discussing his iconic inlaid eagles [image 10], Though others in the region decorated their work with similar eagles, those coming from the Lumbard shop were executed with greater skill, subtlety and grace. The bodies and wings of the birds are curvaceous, using strong cyma outlines. The wings are asymmetrical, giving them a lifelike aspect. The shields they clutch are made of stripes of imported tropical woods. The eagle imagery in Lumbard’s most expensive work speaks to a moment in history when patriotic sentiments were high, the early Republic began to prosper and a new regional style was spreading through southern Worcester County.

Crafting Excellence: The Furniture of Nathan Lumbard and His Circle by Christie Jackson, Brock Jobe and Clark Pearce was published by Winterthur Museum, Garden and Library and is distributed by Yale University Press. For more information, www.winterthur.org or www.yalebooks.com.

Christie Jackson is senior curator, the Trustees of Reservations, Massachusetts. Brock Jobe is emeritus professor of American decorative arts, Winterthur Museum, Garden and Library, Delaware. Clark Pearce is an independent scholar of American arts.