By Madelia Hickman Ring

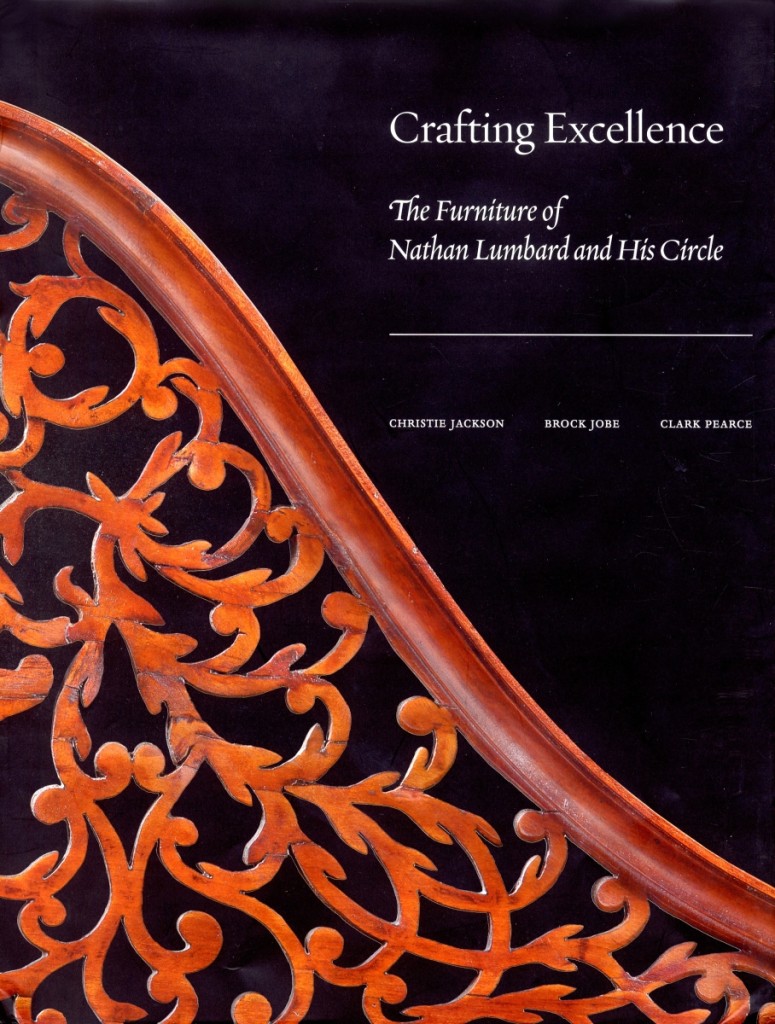

Christie Jackson, Brock Jobe and Clark Pearce’s Crafting Excellence: The Furniture of Nathan Lumbard and His Circle is a long-awaited addition to any American decorative arts reference library. Antiques & The Arts Weekly wanted to point out a few important elements that distinguish it from other monographs on American cabinetmakers.

Perhaps nothing is more important to the uniqueness of the research than the essay by Trustees of Reservations curator Christie Jackson, which relies on an extraordinarily large body of existing documentation, Lumbard family mementoes and contemporary accounts to create a vivid social context in which Lumbard and his contemporaries come alive. Jackson writes that Lumbard’s furniture has a unique quality that continues to be appreciated and that many pieces not only had strong ties to their original owners, but had likely been made for marked celebrations and were, thusly, treasured and passed down with their histories. This, coupled with her discovery of numerous documents and accounts, has allowed for a richer telling of Lumbard’s story.

Like many volumes previously written on American craftsmen, Crafting Excellence follows a conventional methodology in which the authors catalog distinguishing characteristics, outline the shop traditions of the cabinetmaker and list known or closely attributed works. However, with the three authors spread out so widely, a collaborative strategy was necessary. Clark Pearce, speaking to Antiques & The Arts Weekly after the book was published, was quick to point out that the collaborative process added significantly to both the success and breadth of the scholarship. Pearce also acknowledged that each of the authors had located works that the others were unlikely to have been able to find had they been working independently.

Lumbard signed his name on only two of the 61 pieces included in Crafting Excellence, but there are several pieces that are inscribed “Top” in his hand. While the book included 23 pieces attributed to Lumbard, Jobe points out that there are more pieces, approximately another dozen, that warrant a similar attribution, but which were omitted from the book because of similarities to featured ones. A surprising discovery to this writer was the finding that while Lumbard lived until 1847, the bulk of furniture made or attributed to him or the circle in which he was working was made before 1815. Documents survive to indicate that he continued in his trade. Regrettably, examples of his later work have not surfaced, resulting in a frustrating knowledge gap in the material culture of the area.

Brock Jobe’s essay emphasizes that Lumbard occupied a special place within the context of other Connecticut River Valley cabinetmakers, such as William Lloyd, Spooner and Fitts, and Erastus Grant, all of whom were working within the Neoclassical aesthetic. Like his contemporaries, Lumbard was pressed by customers for “furniture in the newest fashion,” but he applied his training and uniquely innovative talents in significantly different ways from his contemporaries. Jobe points to the iconic desk and bookcase [photo 2] at Winterthur Museum as an example of this, ultimately saying of the piece, “No rural craftsman in New England created a more stunning statement of Neoclassical taste.” It is a tour de force of motifs and decorative elements with influences from England, Hartford, Boston and Rhode Island.

Jobe goes on to discuss a swelled-front chest of drawers in the collection of the Henry Ford Museum, which is an unusual form that Jobe credits Lumbard for introducing to New England. It is difficult to imagine two pieces from the same shop being more visually different from each other and the comparison between the two serves to underscore the variety of his production and mastery of his trade. Finally, Jobe acknowledges Lumbard’s legacy as being shaped by his access to new styles and changing consumer tastes, and his existence in an area that was not dictated by urban competition where he could follow his own idiomatic aesthetics.

In his foreword to the book, Philip Zea characterizes the furniture of Lumbard and his circle as a “wooden tapestry” of extensive inlay, delicate carving and fretwork, and classical and nationalistic imagery. Jackson, Jobe and Pearce have woven their scholarship into a lively and informative read that will be enjoyed, and employed, by furniture scholars and collectors for years to come.