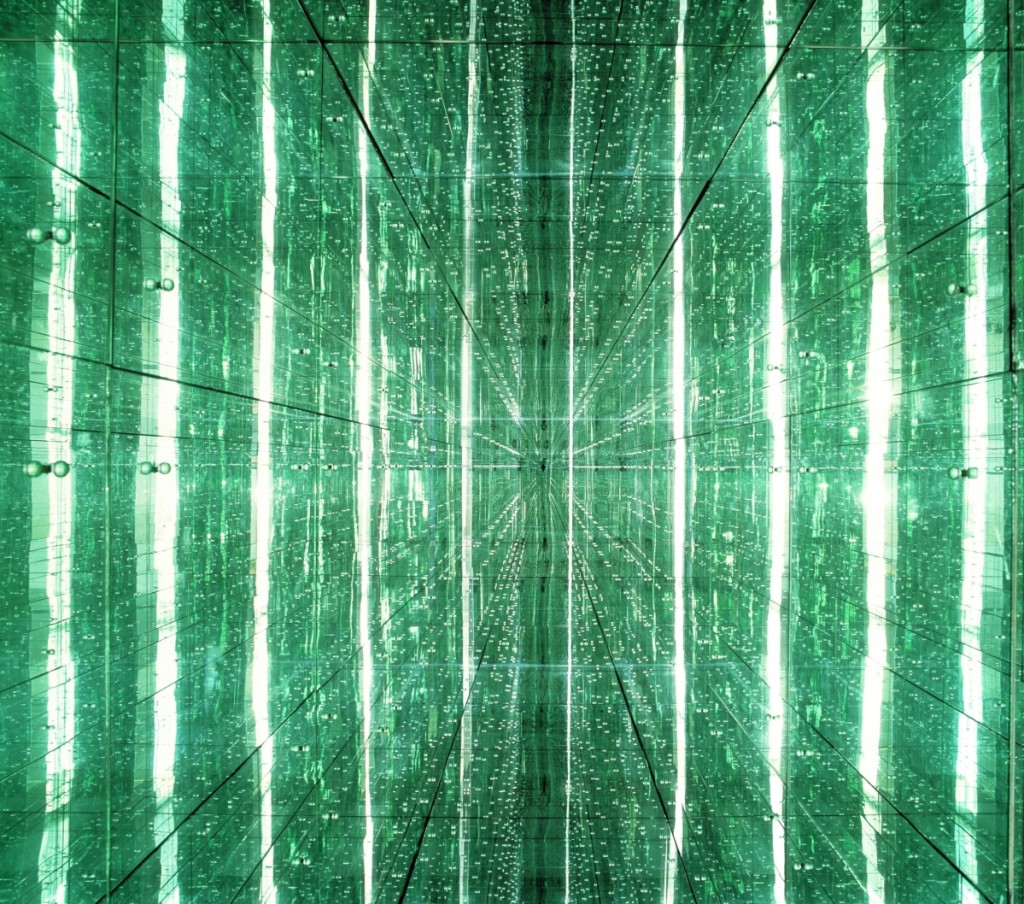

“Corridor #2” by Lucas Samaras, 1970. Mirrors on wood frame, 7 by 3.063 by 50.281 feet. Denver Art Museum Collection: Gift of the artist in honor of Dianne Perry Vanderlip. ©Lucas Samaras.

By Kristin Nord

DENVER – Light. It bathes us, nurtures us, sets our circadian rhythms. It is employed as both symbol and metaphor in poetry and literature. In fine art, it has been harnessed to great effect since ancient times and across cultures. Light can be something we see and dispense with every day, or it can be a spiritual torch, leading us to enlightenment. Some have experienced light as divine revelation; indeed, as the presence of deity itself.

Co-curators Rebecca Hart, the Vicki and Kent Logan Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art, and Jorge Rivas Pérez, the Frederick and Jan Mayer Curator of Spanish Colonial Art, have opened a door for us on this subject, and it would appear they had a great deal of fun selecting art for “The Light Show,” an exhibition that will run while the Denver Art Museum’s (DAM) North Building is in the midst of a major renovation. Through early May 2020, DAM visitors will have a chance to sample some 250 paintings and objects drawn from the museum’s vast holdings – and with 70,000 works on hand, there have been plenty to choose from. The co-curators have set a table for a summertime smorgasbord, and throughout the year carefully choreographed other works will be substituted. Their survey is organized by theme, and draws upon works from the museum’s nine curatorial departments.

The exhibition has been designed to appeal to visitors of all age and includes a number of interactive stations located on levels 3 and 4 of the museum’s Frederic C. Hamilton Building. Exploration kits have been fashioned for families, one titled Puzzles and Play provides a mix of games, riddles and a sketching opportunity, another, called Slow Looking, is designed to help the visitor to consider artworks in new ways.

A visitor begins with light as a physical element, and then soon is off into symbolic and metaphorical realms.

“Religious text, sacred objects and rituals help worshipers find a righteous path,” the curators note, in wall text that has been provided. “While those deemed saints and prophets in many religions serve as intermediaries between believers and the divine, or followers and an ideal. Such messengers often model virtues or behaviors that inspire, elevate and move.”

A brilliant example of this can be found in the DAM’s Tibetan Mandala, a work that was commissioned in 1996 from the Seaje monastery in southern India. The project brought sand mandala master Losang Lungrig; Sonam Woser and Geshe Thubten Sonam to Denver to create this exquisite work. The men were selected for their advanced artistic skills, dexterity and spiritual aptitudes. And they needed to visualize the design, with all of its intricate details, before its meticulous construction could begin.

In Tibetan Buddhism, the Mandala is a powerful symbol. The process of making one is a form of meditation and act of faith in and of itself. Creation reinforces the Buddhist belief in the goal of emptying one’s mind and being in the present, as the work becomes a visual symbol that is beautiful in its conception, composition, color, surface texture, imagery and intricate details. And then, after it is finished, the mandala is dismantled, to signify the impermanence of all things. (DAM’s artwork was granted a special dispensation by the Seaje abbot). The artwork is being shown with a wall tactile created to deconstruct the process for people who might like to make their own mandalas. Those that do will be given the choice of destroying them, or taking them home.

“The Light Show” gives us other stunning examples of light informing religious objects, among them Jacopo Del Casentino’s “Madonna and Child Enthroned with Saints and Angel; Nativity and Crucifixion,” a work believed to have been created by this Florentine artist in about 1340. It belonged to a noble Russian family that fled Russia during the Revolution, and was given in trust to the museum in 1958.

There is the seemingly sun-bathed depiction of “Western Paradise (Taima Mandala),” a work from the Edo period (1600s) of ink, color and gold on silk that measures 43¼ by 37 inches; “Shrine,” a diminutive three-paneled display of virtuosic carving and metalwork believed to have been created in the Eighteenth Century by an unknown Japanese artist; and an 1821 Nepalese Puja lamp with Devotees, made of cast brass and drawn from the museum’s Guthrie-Goodwin collection.

Do we need shadows and shade, and sometimes darkness, to fully appreciate the light? On the third floor, the Shadows and Shade section invites visitors to think about this question as they encounter Indonesian Shadow puppetry, an ancient art form that melds the masterful use of shadow and a puppeteer’s skillful movements. A video of a Javanese performance on spool will bring this form of puppetry to life for all ages.

Hart has selected a fascinating mix of art from her modern and contemporary art department, an arm renowned for its masterworks, from 1900 to today. A spectacular new acquisition, which undoubtedly will be a highlight of the show, is an ornate black chandelier by Fred Wilson, created from clear blown Murano glass, brass, steel and light bulbs, and measuring 4½ feet wide by 6½ feet tall. Wilson is a past recipient of a John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Fellowship, unofficially known as “genius” grant, and he loves nothing better than to select perplexing titles for his works and to decontextualize objects and artifacts found in museums. “The Way the Moon’s in Love with the Dark” once again comes with an inscrutable title – but the work itself, which appeared at the Istanbul Biennial in 2017, blends the virtuosic skills of Ottoman and Venetian glassmakers, in effect bringing two traditionally opposing cultures into a work of creation.

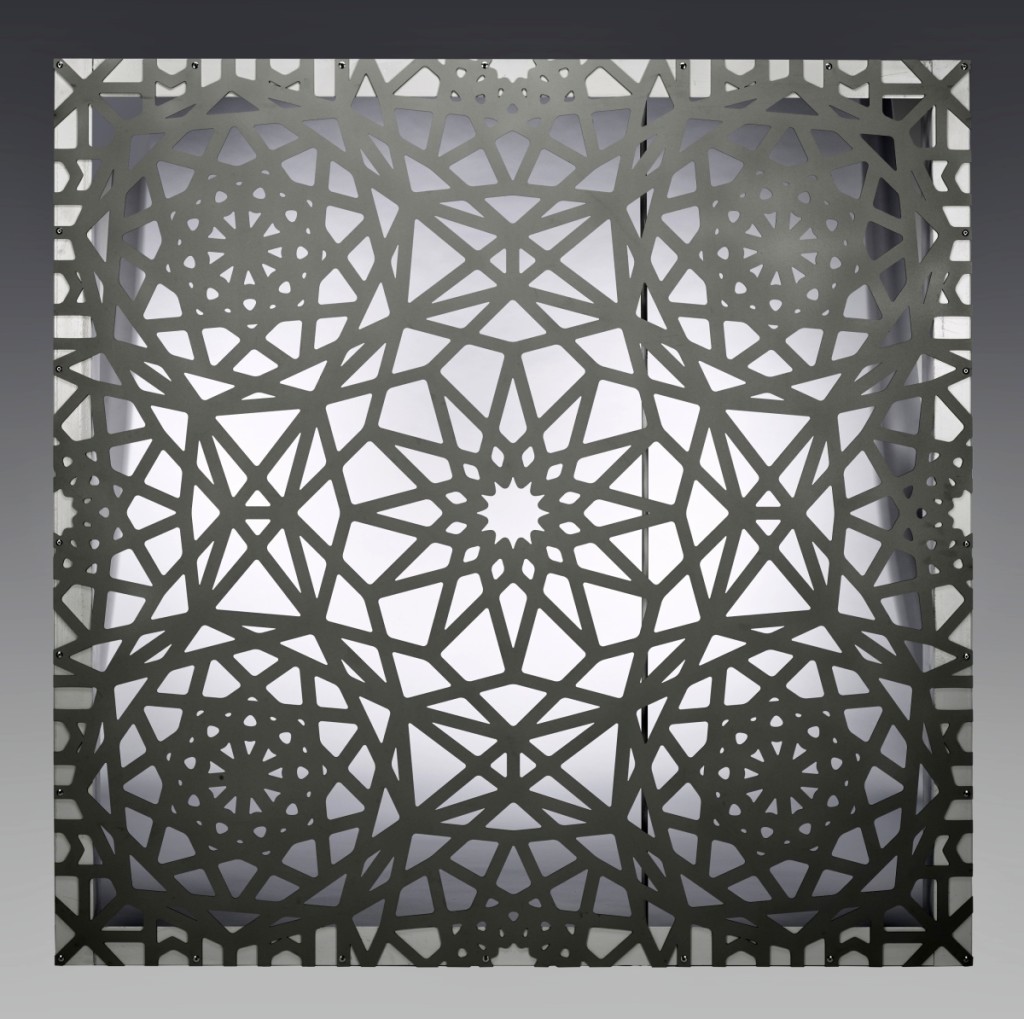

“Infinity Screen Prototype for Lumina” by tres birds workshop, Denver, Colo., 2014. Anodized aluminum and steel, 71 by 71 inches. Denver Art Museum: Funds from Design Council of the Denver Art Museum.

Light figures prominently in other museum favorites, including the Ghanaian artist El Anatsui’s “Rain had No Father?” a work fashioned from bottle tops and copper wire; and Childe Hassam’s painting, titled variously as “A Walk in the Park” or “Springtime in the Park,” believed to have been painted around 1900. The Hassam work is one of 22 major Impressionist paintings that came to DAM in 2014 as part of the Frederic C. Hamilton collection and of one of the 2,000 paintings Hassam would paint en plein air over the course of his working career. Hassam set about to capture his sun-dappled gardens and coastal scenes in varied weather, and he loved capturing the reflections of artificial illumination in cities as well.

We see the use of reflections transforming space in Lucas Samaras’ “Corridor #2,” a massive work of mirrors on a wood frame that has not been on view since 2003. At the same time Ettore Sottsass’ anthropomorphic Ashoka lamp challenges our ideas about useful lighting as it straddles the line between domestic objects and sculpture. This lamp was one of the first designs produced by the Memphis group, an Italian design collective founded by Sottsass in 1980. Memphis designers used unexpected materials and surprising shapes and proportions in their furniture and lighting. As for exquisite objects, this one seemingly conjuring a sun-kissed morning, one cannot go wrong with Shunsho Hattori’s display box (Kazaribako) “Morning Glow,” a 1999 creation of lacquer, gold and abalone shell inlay on wood. This object was given to the museum in honor of longtime Asian curator Ronald Otsuka to commemorate his illustrious 30-year career.

“Can we truly appreciate light without shadow?” the curators ask. Both light and darkness generate patterns and distortions and may play tricks on our eyes as an object of place is transformed.

The importance of light and shadow is predominant in two silver gelatin prints. The first, by Ansel Adams, titled “Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico,” 1944, seems a poignant portrayal of loneliness. In the cameraless body of work for which Floris Michael Neusüss has made his reputation, this 1988 work, “Lichtlaufzeiteffekt (Light-Motion-Time Effect),” succeeds in disengaging the viewer from time and the physical world. Neusüss is known for works that juxtapose opposites – black and white, light and shadow.

It is in moments of crisis or despair that we often experience darkness. We languish in limbo, awaiting a decision or a resolution and experience this liminal phase, curator Peréz observes, as an underworld or otherworld.

This is where we encounter La Muerte in José Inez Hererra’s “Death Cart,” a folk-art treasure fashioned from wood, leather, hair, feather, metal and silk. This distinctive art form originated in Spanish religious drama and is known in particular in the region of Cordova, New Mexico and Southern Colorado. This one was believed to have been made between 1890 and 1910 by the artist active in El Rito, N.M. Death carts appear in Good Friday processionals and foretell the miracle of Christ’s ultimate triumph over death.

Where exactly has this excursion taken us? The curators hope visitors will leave, perhaps with light bulbs – as ideas – going off, and their senses sated. “Since the beginning of time, light has provoked enduring questions about the nature of existence, and we hope this will challenge visitors to think more deeply about our known and unknown surroundings,” Hart says.

The Denver Art Museum is at 100 West 14th Avenue Parkway. For additional information, www.denverartmuseum.org or 720-865-5000.

_rain_has_no_father_2008.jpg)

_17th_century.jpg)