“Moon over Harlem” by William Henry Johnson (American, 1901-1970), circa 1943-44, oil on plywood, framed: 35-7/8 by 43-1/8 by 2½ inches. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington DC. Gift of the Harmon Foundation. Image ©Art Resource, NYC.

By Kristin Nord

NEW YORK CITY — “They fled as if under a spell or a high fever. They left as though they were leaving some curse,” the scholar Emmett J. Scott writes, in Isabel Wilkerson’s Pulitzer-prize winning book, The Warmth of Other Suns. “They were willing to obtain any sacrifice to obtain a railroad ticket, and they left with the intention of staying.”

From the First World War until the Second World War, an estimated two million African Americans fled the segregated South for major urban centers in the North. This diaspora set in motion, Wilkerson writes, “changes in the North and South that no one, not even the people doing the leaving, could have imagined at the start of it or dreamed would take nearly a lifetime to play out.”

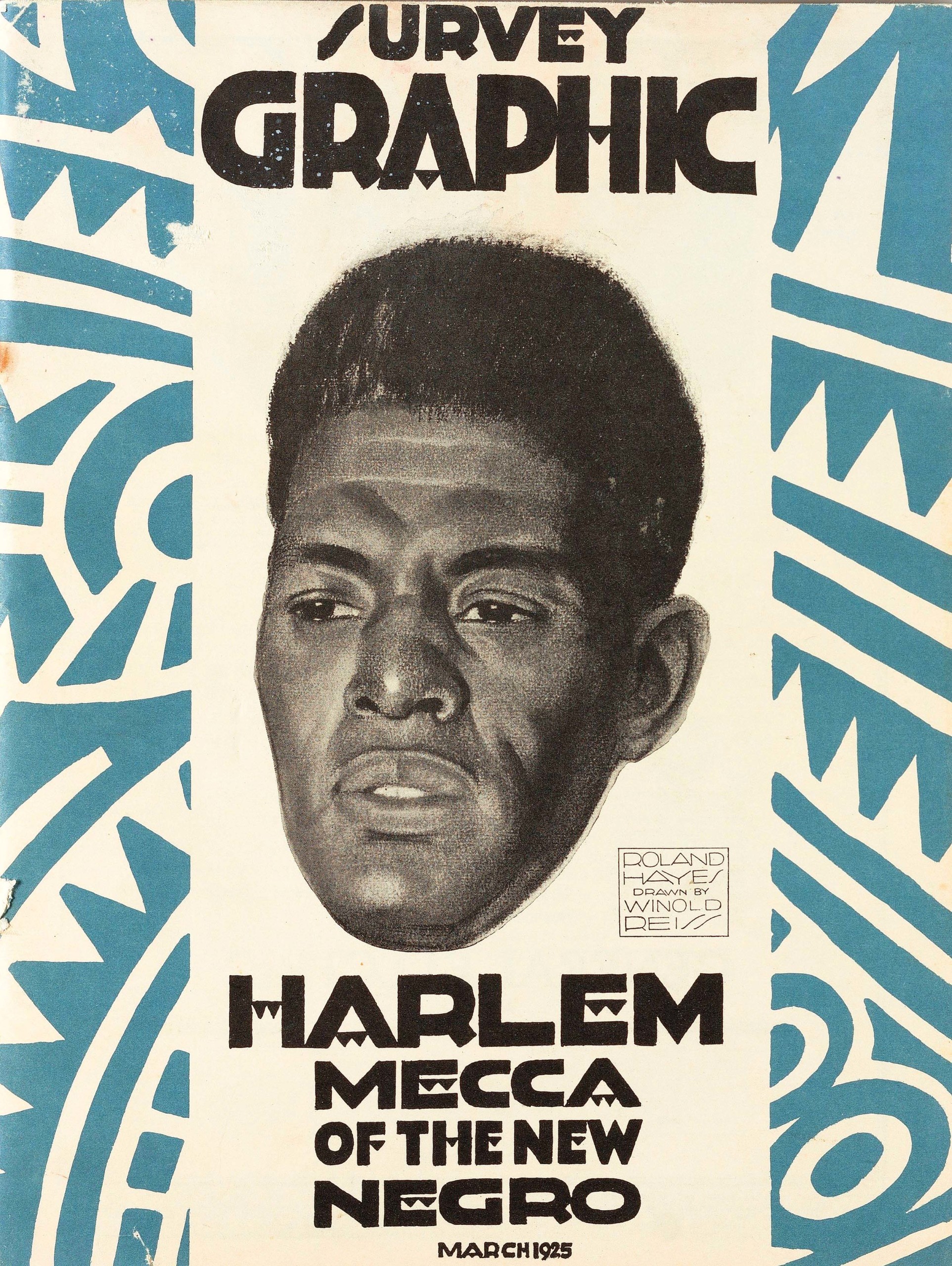

Now, in “The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism,” on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art through July 28, we encounter the remarkable art that this diaspora spawned. Harlem would become known as the African American cultural mecca, but art flourished in other emerging new Black cities as well. And the fact that Black artists could live and work abroad, now brought them into contact with modernist artists from around the globe. Denise Murrell PhD, the Merryl H. and James S. Tisch curator at large, has made it part of her mission to place the contributions of African American artists within the context of this new movement and to show how crucial their contributions were.

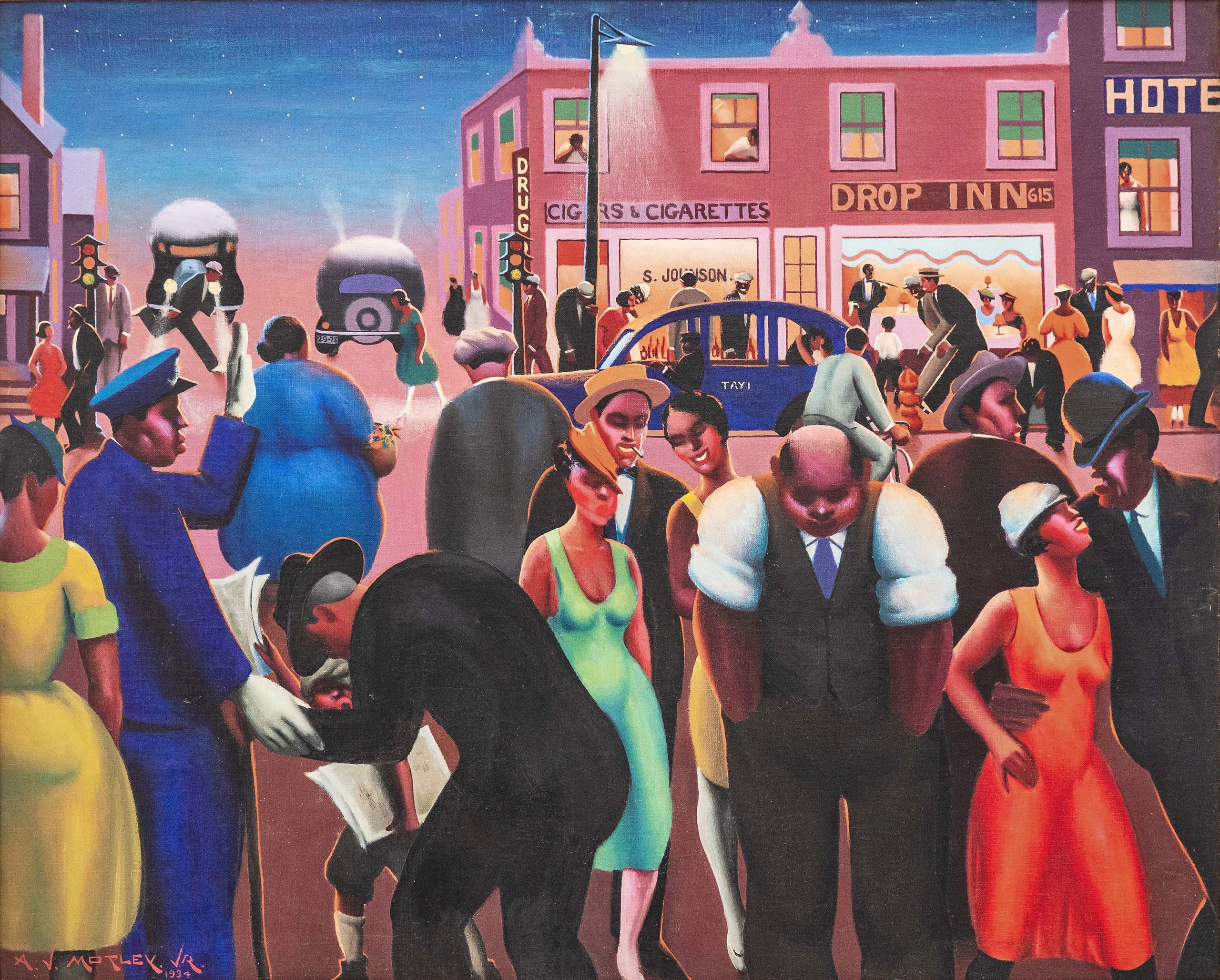

“The Picnic” by Archibald J. Motley Jr (American, 1891-1981), 1936, oil on canvas, 30 by 36 inches. Howard University Gallery of Art, 47.22.P. ©Estate of Archibald John Motley Jr. All reserved rights 2023 / Bridgeman Images. Image ©The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Juan Trujillo photo.

This is the first survey of the Harlem Renaissance at the Met in 40 years, and, while not an obvious mea culpa for its disparaged 1969 exhibition, “Harlem on My Mind,” it will go a long way toward filling in great gaps in history. Quite possibly it will inspire a much more inclusive American art history survey course in the future. The 1969 exhibition, which was part of the museum’s 100th anniversary celebrations, ignited a firestorm when it opened devoid of work by a single Black artist. In the decades since and through the concerted efforts of the Met’s longtime assistant curator Lowery Stokes Sims, the museum set about acquiring dozens of important works by Black, Latinx and Indigenous artists.

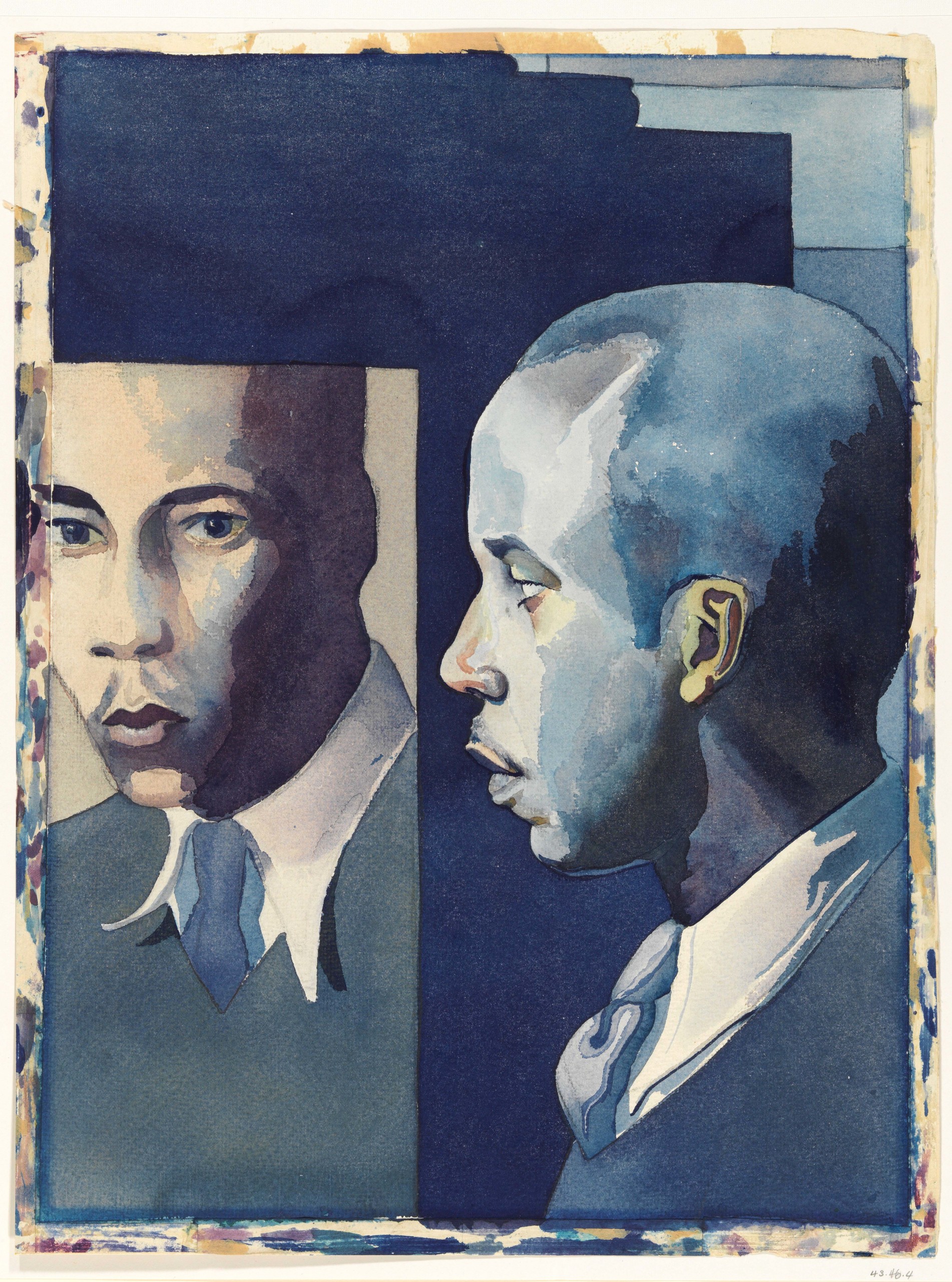

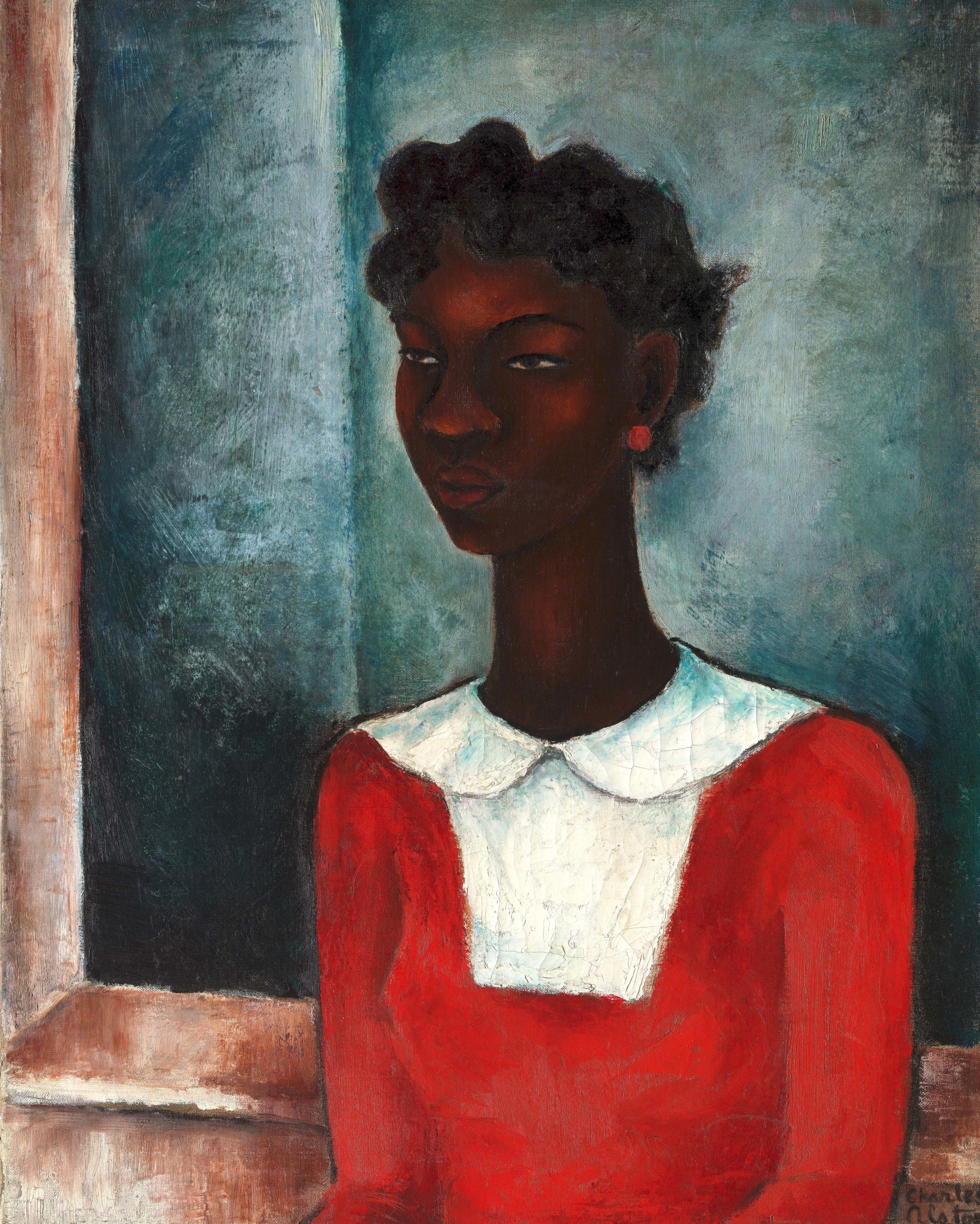

Among the institution’s acquisitions, for instance, was Charles Henry Alston’s “Girl in a Red Dress,” which is seen as an iconic work from the “New Negro” movement. In it, a regal young woman with an elongated neck and a sculptural idealized face, is seated, evoking the Fang busts of West Africa. This work is very much in keeping with the ideas of leading African American philosopher of the Harlem Renaissance, Alain Locke, who urged Black artists to embrace their ancestral heritage and seek inspiration in contemporary folkways.

“Girl in a Red Dress” by Charles Henry Alston (American, 1907-1977), 1934, oil on canvas, 28 by 22 inches. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Purchase, Lila Acheson Wallace Gift and George A. Hearn Fund, 2021. ©Estate of Charles Henry Alston. Image ©The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

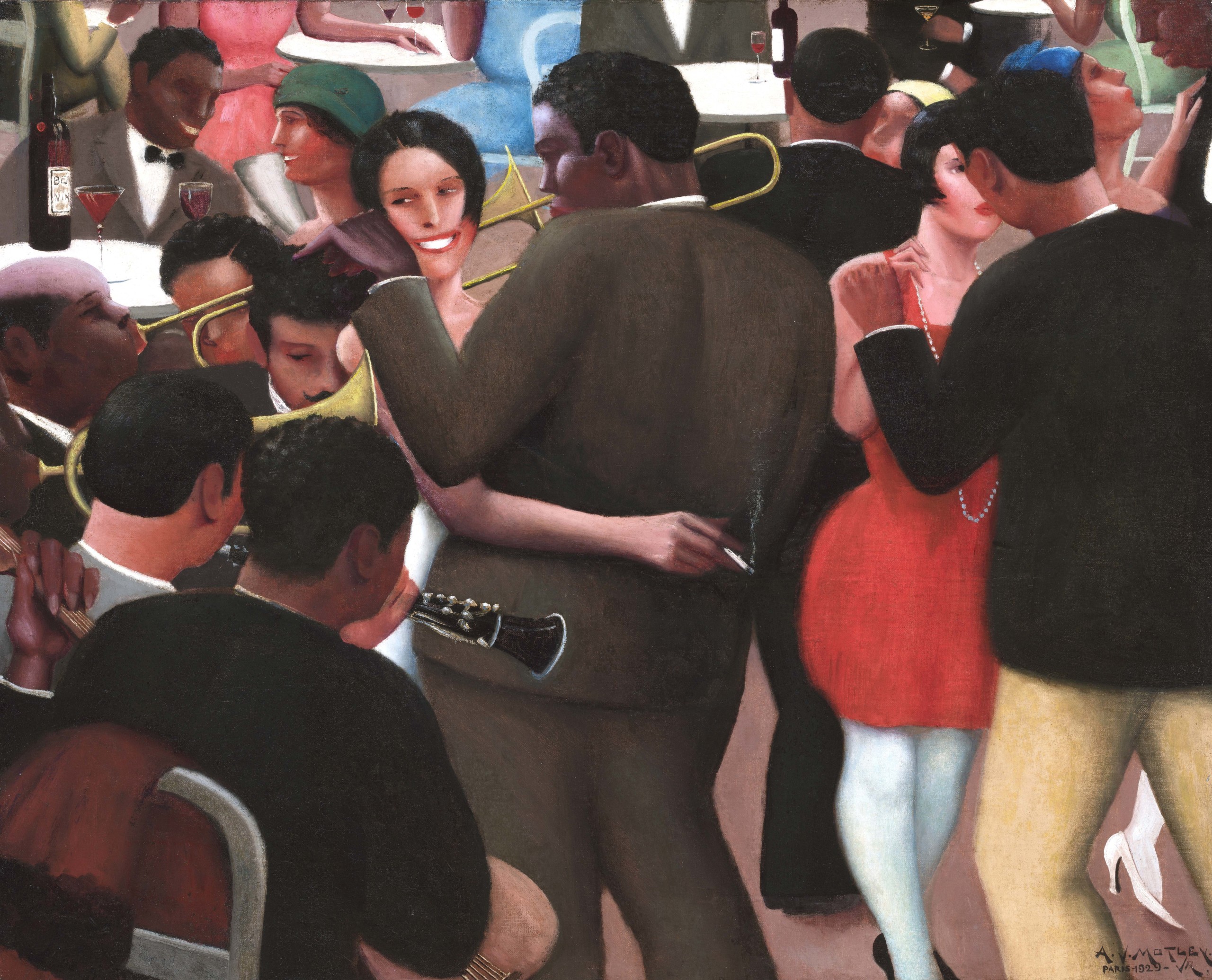

From the 1910s through the late 1940s, Harlem was a living breathing marketplace for ideas, intellectual discourse, poetry, literature, dance and jazz. It supported churches, dance halls, parades and processions, and homes where an emerging African American middle class resided with dignity. From street scenes to pool halls and gambling backrooms, to living rooms where elegantly attired women gathered for cocktails during Prohibition, it was a happening place. Couples jitterbugged in the Savoy Ballroom; everyday scenes inspired art and one form of art often inspired another. Yes, African Americans faced persistent racial discrimination, and yet, in the dignity of a Lenox Street procession, captured by James Van Der Zee, viewers can’t help but feel the pride and glimmers of hope in the sea of well-dressed men marching in unison. A succession of Harlem’s parades left their traces on the annual calendar, and included the NAACP’s Silent Protest March of 1917, the Harlem Hellfighters’ homecoming parade of 1919 and Marcus Garvey’s UNIA parades. Five of Van der Zee’s legendary photographs, from a massive archive now owned and conserved by the Met, work well in this show as a connecting thread. In some ways they record what in hindsight were the innocent precursors to the non-violent marches of the civil rights era.

Murrell has made a particular note to help explore the ways in which African Americans maneuvered and flourished in the global multi-ethnic circles of Paris, London and Northern Europe.

“Couple, Harlem” by James Van Der Zee, (American, 1886-1983), 8 by 9-15/16 inches. James Van Der Zee Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art; Gift of Donna Van Der Zee, 2021. 2021.446.1.2. ©James Van Der Zee Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In “The Legacy of the Ancestral Arts,” his essay published in Primitivism and Twentieth-Century Art (2003), Locke wrote, “The New Negro is a far more familiar figure in American life than in European, but American art, barring caricature and genre, reflects him scarcely at all…whereas in Europe, with the Negro subject rarely accessible we have…an interest that in contemporary French, Belgian, German and even English painting as brought forth work of singular novelty and beauty.” Murrell underscores her points by juxtaposing the African American artists with works by Matisse, Munch, Picasso and others.

Thanks to Murrell’s due diligence, the Met has secured loans for artists who are lesser known but deserve to be in the spotlight.

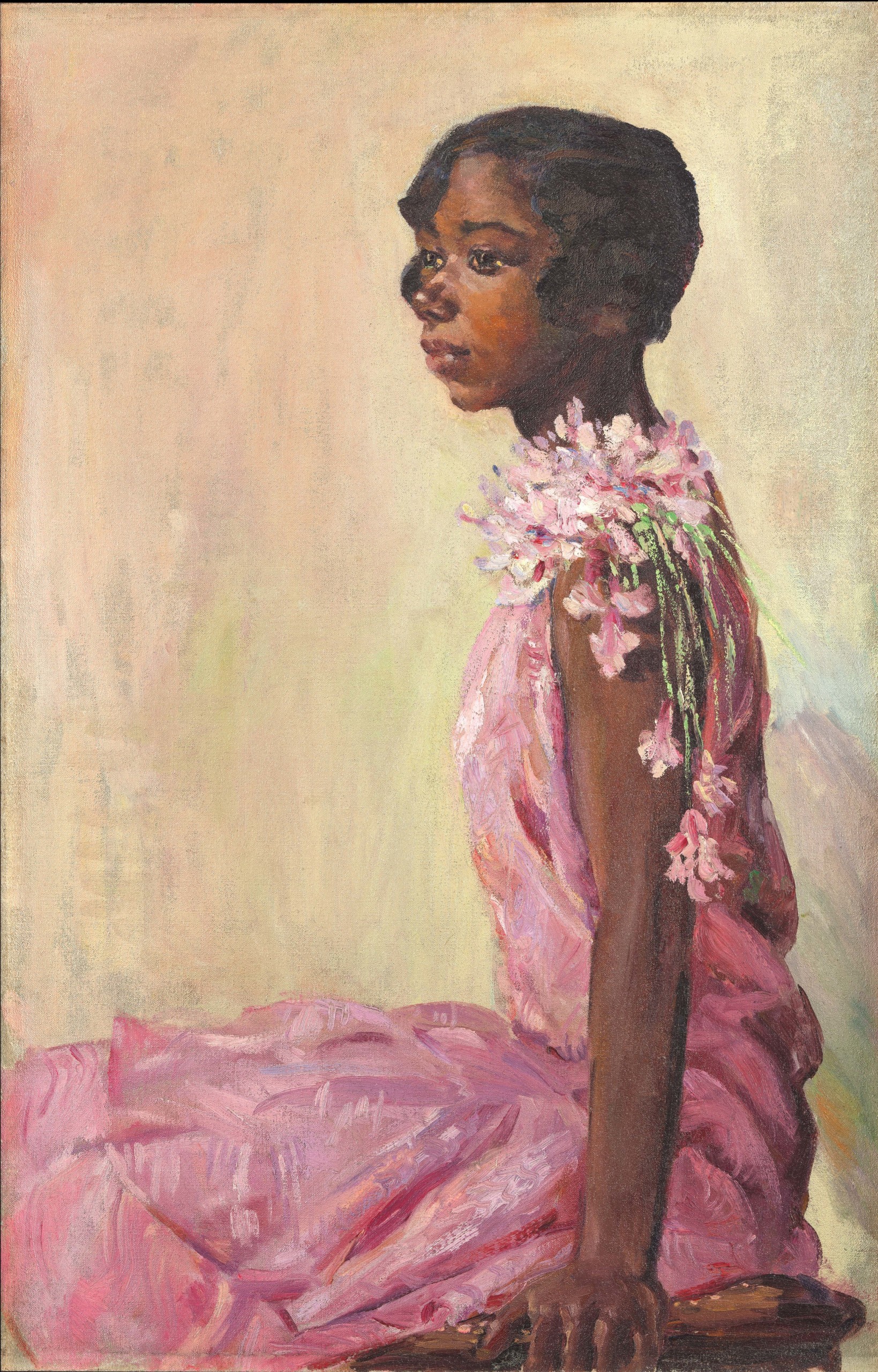

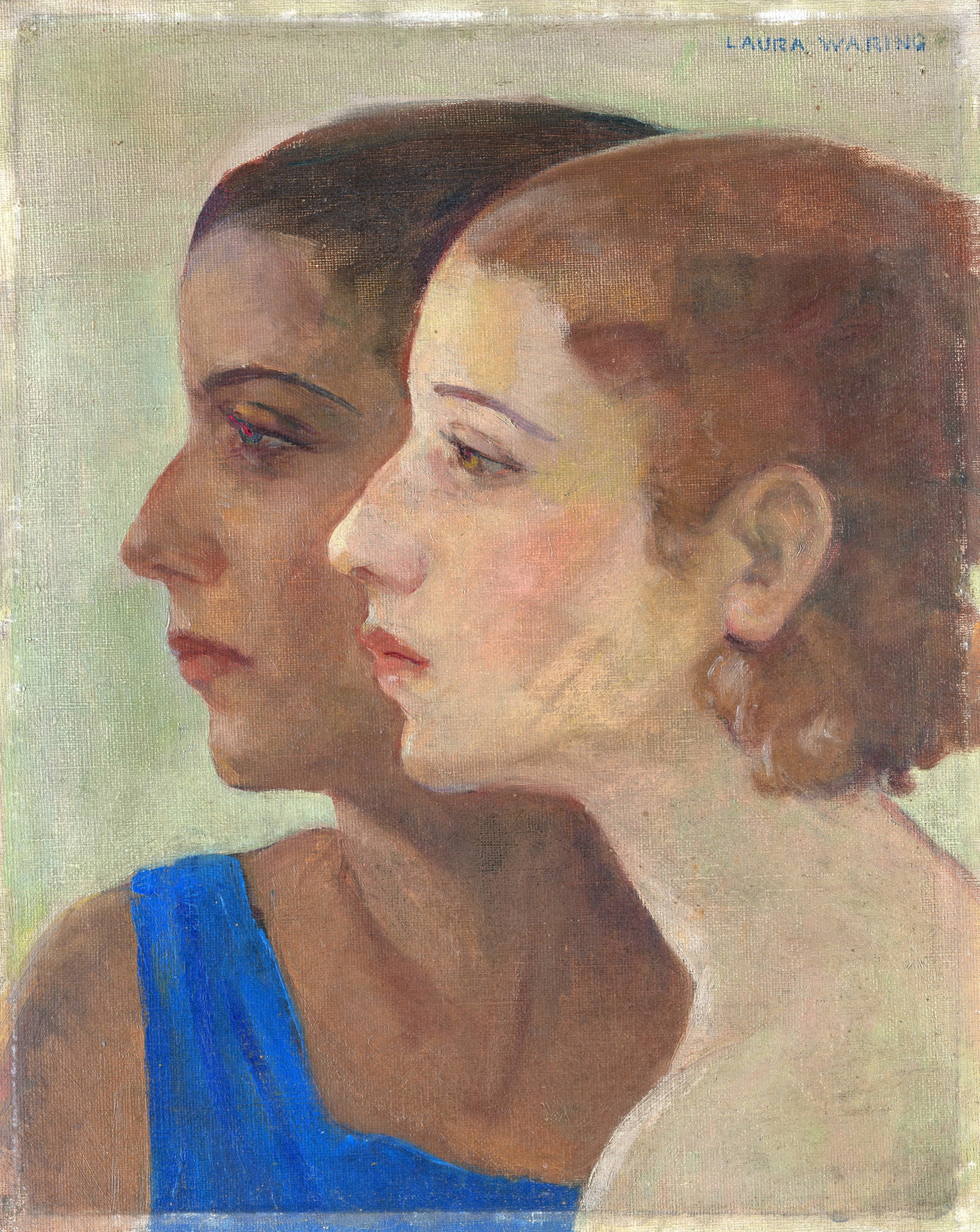

Pioneering educator and painter Laura Wheeler Waring, a Hartford, Conn., native who studied at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts and pursued further study in two separate sojourns in Europe, is one.

Waring’s landscapes and murals in her day gained her wide acclaim, but today she is most remembered for her portraiture — of Black luminaries, such as Marian Anderson, James Weldon Johnson and W.E.B. DuBois. Three stunning portraits of women, in works by Waring titled, “Pomegranates,” “The Girl in a Green Cap” and “Mother and Daughter,” we find clues that place these women within the hierarchies of Black culture and suggest how some Black families of means wished to be seen.

“Mother and Daughter” by Laura Wheeler Waring (American, 1887-1948), circa 1927, oil on canvas, 19 by 15-7/8 by 1¼ inches. Collection of Roberta Graves. ©Laura Wheeler Waring Image ©The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Juan Trujillo photo.

Murrell scoured the landscape to secure loans from the extensive collections of Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs), including Clark Atlanta University, Fisk University Galleries (Nashville, Tenn.), Hampton University Art Museum (Hampton, Va.) and Howard University Gallery of Art (Washington DC). The Schomburg Center of Research in Black Culture (New York City), the Smithsonian American Art Museum, and the National Portrait Gallery, both in Washington DC, have also made significant loans for this comprehensive overview.

Among the 160 works on view are paintings, sculptures, murals, photographs and ephemera, with significant works by Charles Henry Ashton, Aaron Douglas, Palmer Hayden, William H. Johnson, Archibald J. Motley Jr, Winold Reiss, Augusta Savage, Roy DeCarava, Hale Woodruff and Beauford Delaney. The exhibition concludes with Romare Bearden’s 15-foot series of collages of a Harlem townhouse row in midcentury.

Murrell hasn’t shied away from the culture wars within the culture itself and its inherent Black tensions. One can expect these issues will get further attention in both a five-episode podcast that the Met has underwritten, and a Met-sponsored symposium that will take place in April. Walking tours of Harlem have been designed to help the curious experience this history and culture on foot.

“Luncheon Party, Harlem” by James Van Der Zee (American, 1886-1983), 1927, gelatin silver print, 7½ by 9½ inches. Gift of James Van Der Zee Institute, 1970 1970.539.11. ©James Van Der Zee Archive, The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

While Locke had promoted The New Negro aesthetic in “The New Negro: An Interpretation;” W.E.B. Du Bois, the social historian, advocated for Black art “inflected by the classical tradition, imbuing Black subjects from across the spectrum with dignity and historical gravitas.” At the core of this exhibition are the artists who shared a commitment to capturing modern Black life in a radically modern way.

Yet as the Black population had settled into northern cities, African American artists struggled to gain acceptance or access to the marketplace. Winning a Harmon Foundation Award in the late 1920s would have elevated an artist’s reputation but could not guarantee that he or she would be able to break into the exhibition world of white America.

In “The Legacy of the Ancestral Arts,” Locke wrote, “…There is a vital connection between this new artistic respect for African idiom and the natural ambition of Negro artists for a racial idiom in their art expression” “…The Negro physiognomy must be freshly conceived on its own patterns”…“Art must discover and reveal the beauty which prejudice and caricature have overlaid.”

Harkening back to Charles Alston’s “Girl in a Red Dress,” the art scholar Richard Powell notes that the artist was also aligning with the modernist aesthetic by embracing flatness and tonalities that mirrored European strategies. The woman is “defiantly Black, beautiful, and feminine, yet also unsettled, mysterious and utterly modern,” he writes. In William H. Johnson’s striking depiction of a character identified simply as, ‘Woman in Blue,’” Murrell writes, “the artist’s use of bold flat impasto color and the subject’s masklike inscrutability — intensify the portrayal of a urbane personality who, with her wide-eyed gaze and cool self-assurance, insists upon her own terms of engagement.”

“Woman in Blue” by William Henry Johnson (American, 1901-1970), circa 1943, oil on burlap, framed: 35 by 27 inches. Clark Atlanta University Art Museum. Permanent Loan from the National Collection of Fine Art, 1969.013. Courtesy Clark Atlanta University Art Museum. Mike Jensen photo.

These are two of the everyday people African American modernists were encountering in this new age. They too, like James Baldwin, Miles Davis, Marion Anderson and Bessie Smith, were arrivals to new destinations — and their prospects for better lives were derived in part from the sacrifices their forebears had made.

Langston Hughes would write, “We younger Negro artists who create now intend to express our individual dark-skinned selves without fear or shame…If ‘We know we are beautiful. And ugly, too…if colored people are pleased, we are glad. If they are not their displeasure doesn’t matter.”

“We build our temples for tomorrow, strong as we know how, and we stand on top of the mountain, free within ourselves.”

“The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism” will remain on exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art through July 28.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art is at 1000 Fifth Avenue. For information, 212-535-7710 or www.metmuseum.org.