“Lobster Buoys” by Jacqueline Hudson (1910–2001), 1971, oil on panel, 22 by 30 inches. Bequest of Jacqueline Hudson, 2002.

by Jessica Skwire Routhier

MONHEGAN, MAINE – Life on a Maine island can have its limitations. On Monhegan, nearly 12 nautical miles offshore, nearly everything a person needs must be brought in by boat. There are no cars on the island, so residents and visitors go everywhere on foot, carrying backpacks, trailing wheeled suitcases and lugging bags of groceries and painter’s easels. By 4:30 pm, the last ferry has left. Until the morning boat, those who remain are effectively socked in for the night – no hardship in the summertime, but a battle against the dark Atlantic cold in the winter.

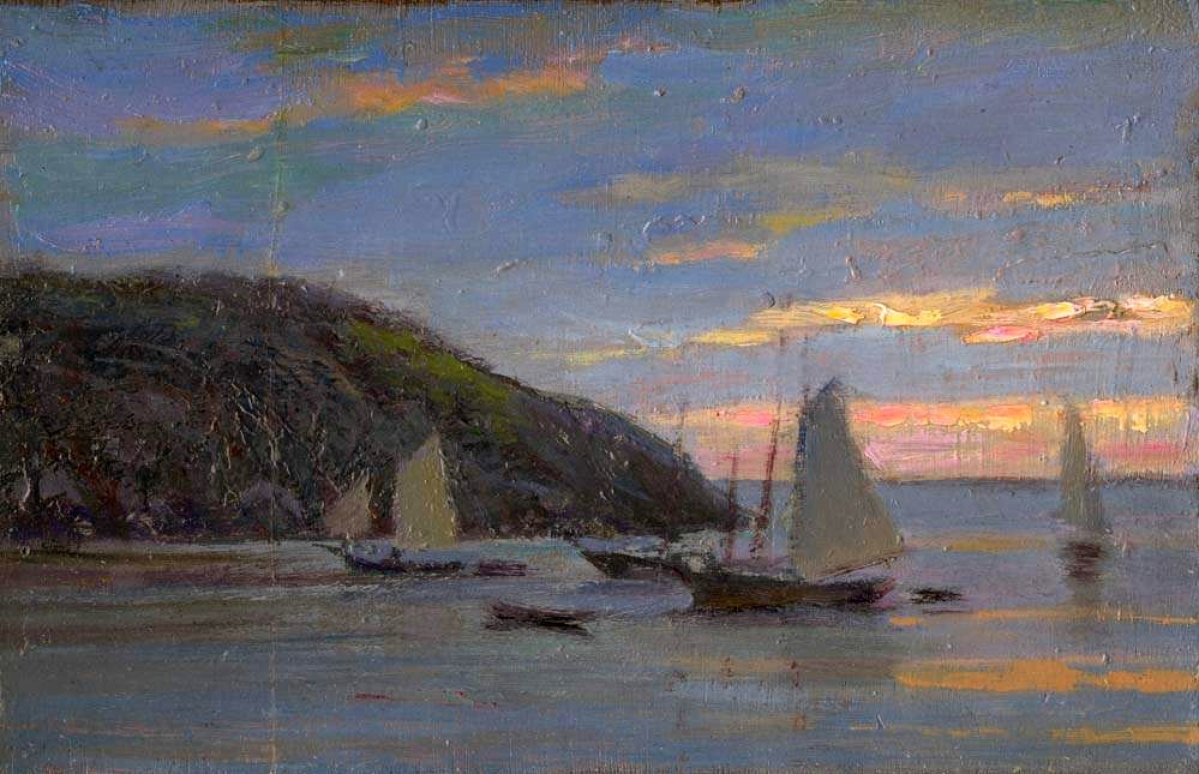

Yet for nearly 160 years, artists of international significance have relished such challenges as assets, visiting and working on Monhegan for generations: Robert Henri, Rockwell Kent, Louise Nevelson, Andrew Wyeth, Lynne Drexler and many others. Much in the way that strict design limitations for a commission or a competition can often spur unprecedented creativity, Monhegan’s isolation, small footprint and relatively closed community have enabled its artists to push the limits of what is possible. Collectively and over time, they have created a canon of work that is as complex, rigorous and transformative as that of any other art colony, and arguably far more stylistically diverse. In this anniversary year, the Monhegan Museum offers a visual overview of the island’s artistic legacy with “The Monhegan Museum: Celebrating Fifty Years,” on view through September 30.

The Monhegan Museum itself has some intriguing design limitations. Situated in a historic light station at the island’s highest point – with an impossibly picturesque view of Monhegan village, the harbor and Manana Island just beyond – the museum takes seriously its mission to preserve the unique physical character of the island. There is no multimillion-dollar, architect-designed, glass-and-steel, benefactor-named building here. The museum has long occupied the original, 1860 lightkeeper’s house and adjacent buildings. When the collection’s size and needs grew enough to require expansion, the museum in 1998 consulted the original Coast Guard plans and historic photos to recreate the assistant keeper’s house, destroyed in the 1920s. Identical to its historical antecedent on the exterior, it is a bright and modern gallery on the inside, currently housing the larger part of this summer’s exhibition.

Walking through this section of the show, longtime museum director Ed Deci describes other ironclad parameters the museum adheres to. For one, it does not, and has never, exhibited the work of living artists – despite the scores of contemporary artists working on the island today. “We’re a small community, and there’s a lot of art in this community, and we just didn’t want to get into the politics of who gets selected and who doesn’t,” Deci says, pointing out that even with this limitation, there is no shortage of work to exhibit. “There’s sort of the joke that artists are dying to get into the Monhegan Museum,” he adds, attributing the quip to Monhegan artist Don Stone. Stone passed away in 2015 and has thus earned his place in the museum’s collection and the current exhibition.

Further setting the Monhegan Museum apart is the fact that it has never purchased a work of art for its collection. Everything has come to it as a gift or bequest. Considering the depth and quality of its collections (Deci says it has about 1,500 art objects and 30,000 objects overall), it is an impressive example of what is possible within circumscribed boundaries.

Further setting the Monhegan Museum apart is the fact that it has never purchased a work of art for its collection. Everything has come to it as a gift or bequest. Considering the depth and quality of its collections (Deci says it has about 1,500 art objects and 30,000 objects overall), it is an impressive example of what is possible within circumscribed boundaries.

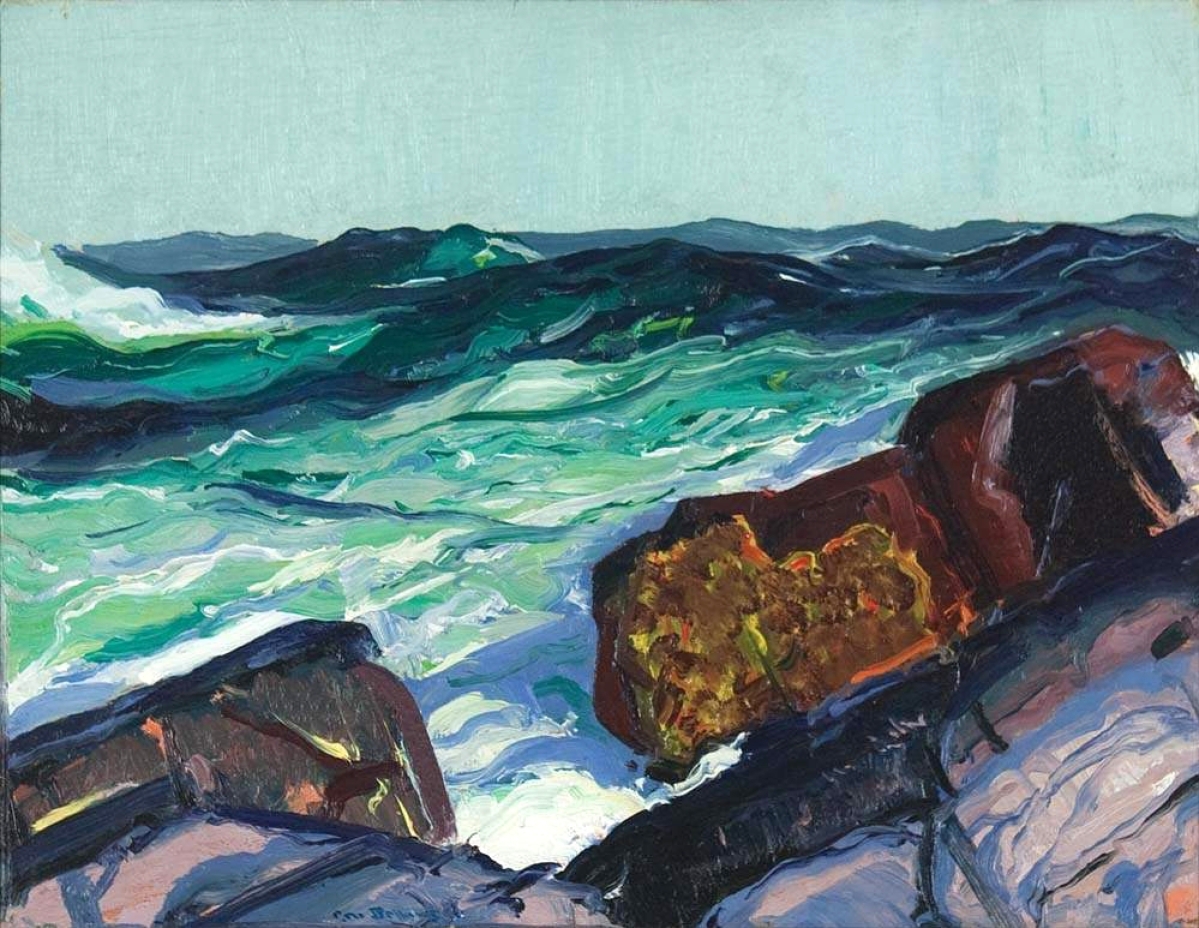

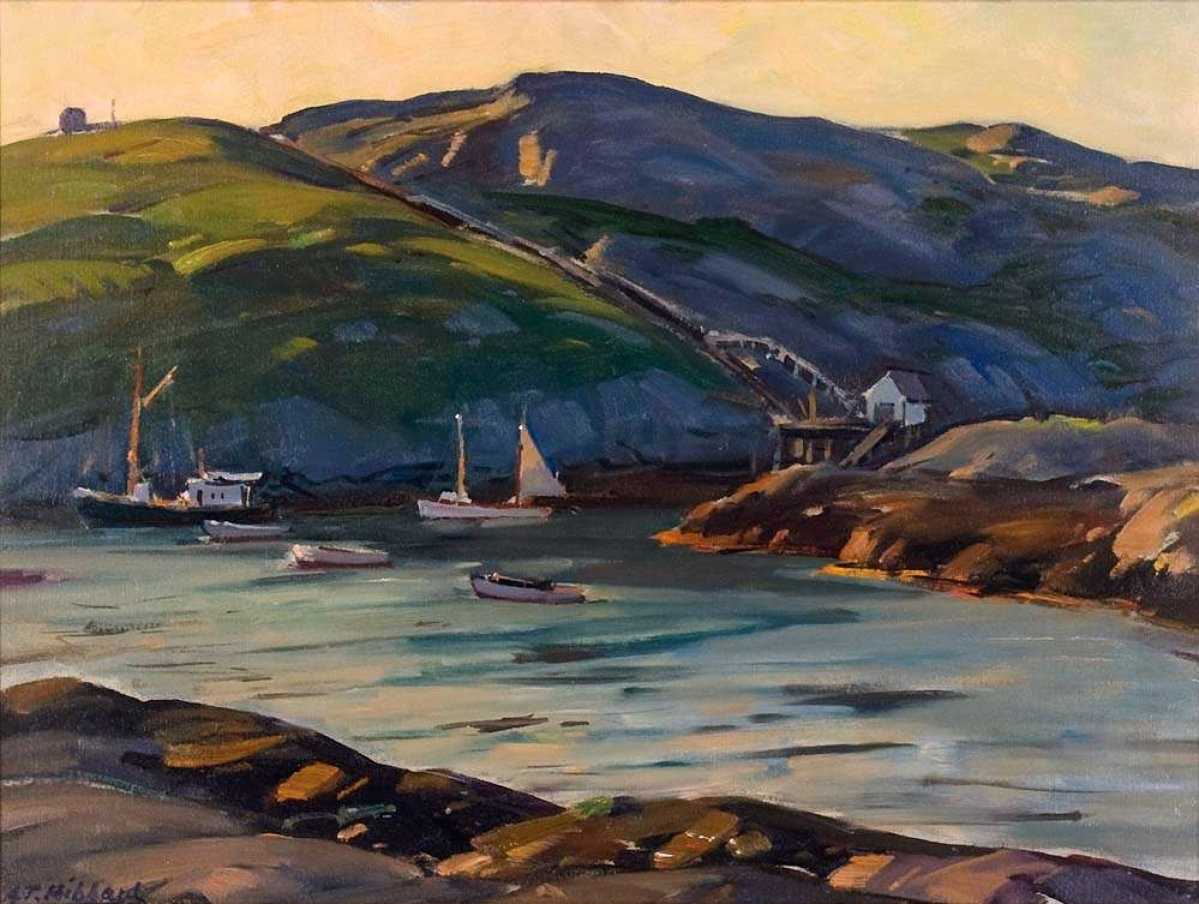

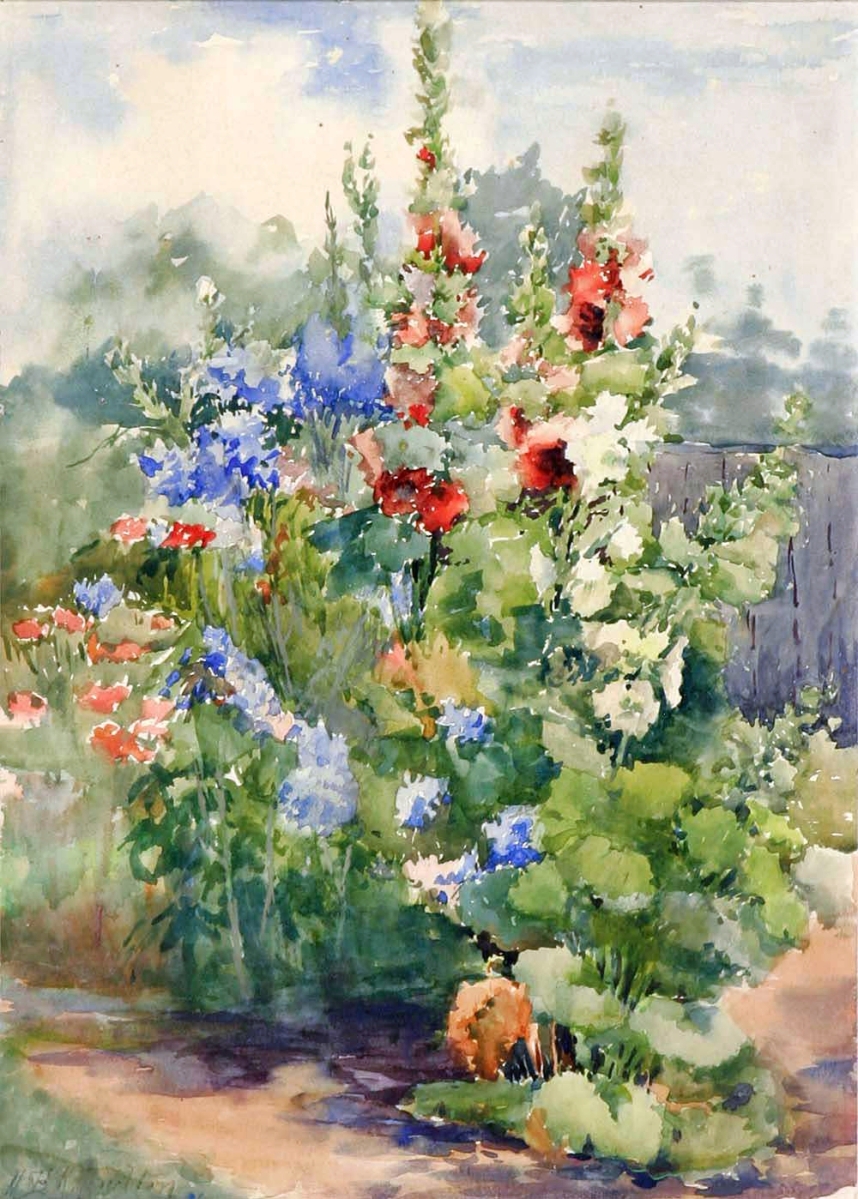

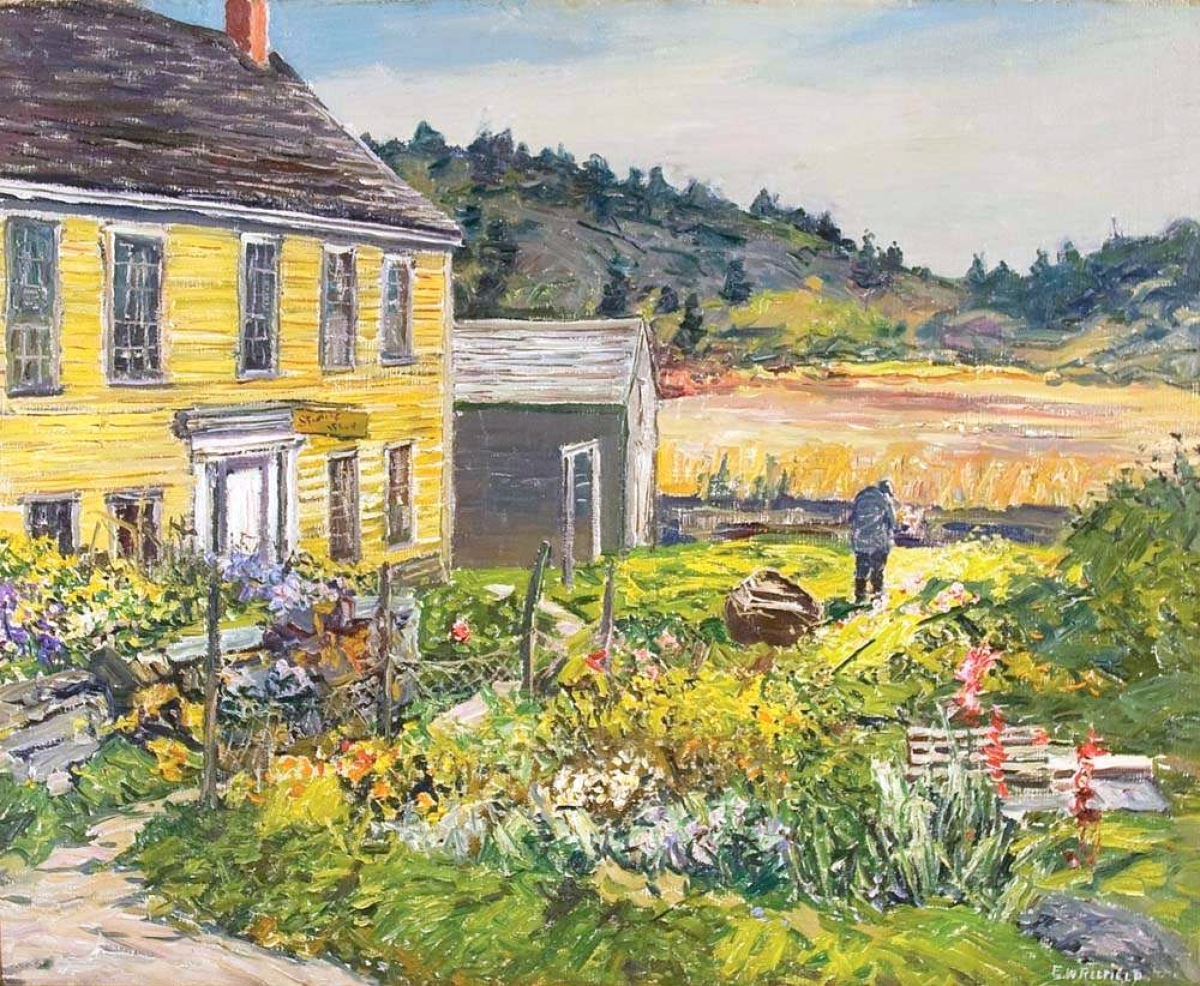

Yet another design limitation was put into play in the organizing of this exhibition. Although an exhibition heavy on Kents and Wyeths would no doubt have been popular, the curatorial team of Deci, Associate Director Robert L. Stahl (also executive director of the affiliated James Fitzgerald Legacy) and Chief Curator Jennifer Pye wanted to include as many Monhegan artists as they had room for. They set themselves a rule: only one work by each artist. One watercolor by Maud Briggs Knowlton, a founding female member of the Monhegan art colony and, later, director of the Currier Museum of Art in New Hampshire; one painting by George Bellows, who followed his teacher Robert Henri to the island and, like him, made luscious, painterly seascapes in the first years of the Twentieth Century; just one melting, late-career sunset by Rockwell Kent, who is one of the few artists to have lived on the island year round, in a home and studio he built himself; and one black-painted wood assemblage by Louise Nevelson, a miniature version of the large abstractions for which she became famous, and that she claimed were inspired by Monhegan.

“I love this,” says Deci, gesturing to the Nevelson piece, “because we’re small and it’s small.” He notes that in the 1970s Nevelson, recently returned from Paris, told a biographer that she had seen nothing in the Louvre that excited her as much as the driftwood shacks of the self-described hermit who lived on Manana.

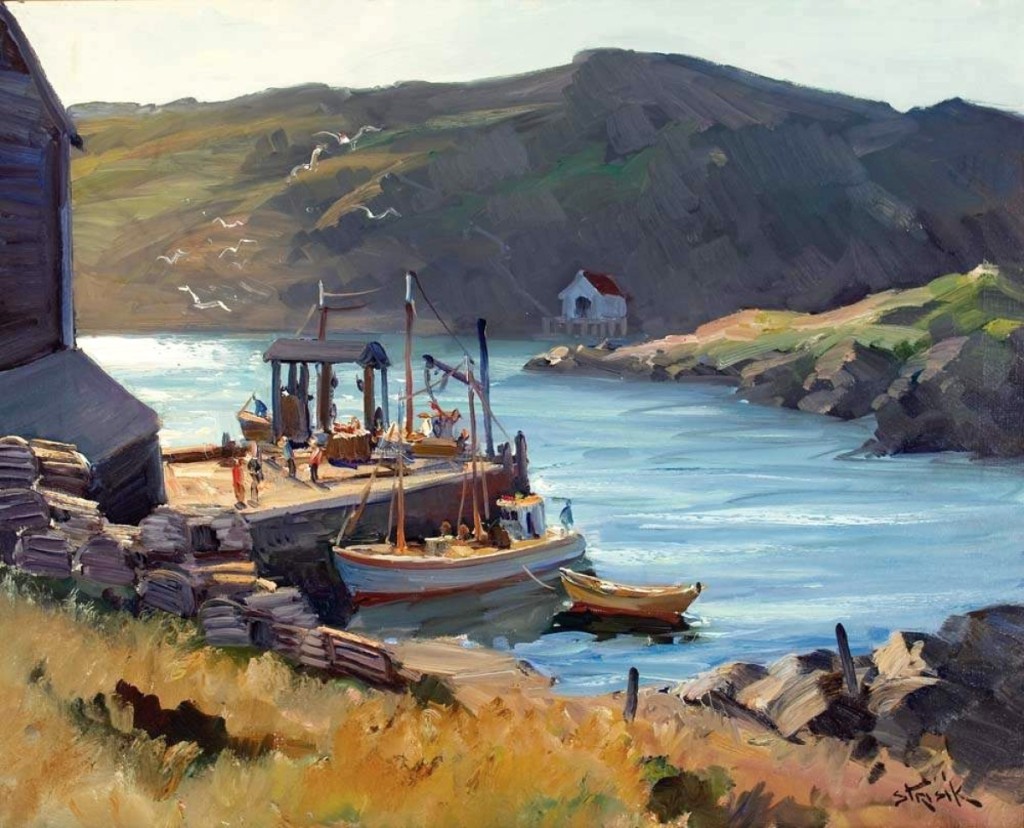

The second part of “The Monhegan Museum: Celebrating Fifty Years,” on view on the second floor of the original lightkeeper’s house, focuses on the artists who came to work and be inspired by Monhegan in the postwar period (though again, no living artists are on display). Works on view include Stone’s scene of painters at work on the beach; Drexler’s pebbly abstraction reminiscent of the rocky shore at Lobster Cove; colorful abstractions by Michael Loew and Zero Mostel, who Deci says claimed that “the only reason he acted was to have enough money to buy paint and canvases”; a watercolor by Charles E. Martin that became a New Yorker cover; and numerous other delights by Joseph DeMartini, Alan Gussow, John Hultburg, Elena Jahn, Frances Kornbluth, Paul Strisik, Reuben Tam and many others.

“The Old War” by Jay Hall Connaway (1893–1970), mid-Twentieth Century, oil on canvas, 26¼ by 36 inches. Gift of John Gummere, 2008.

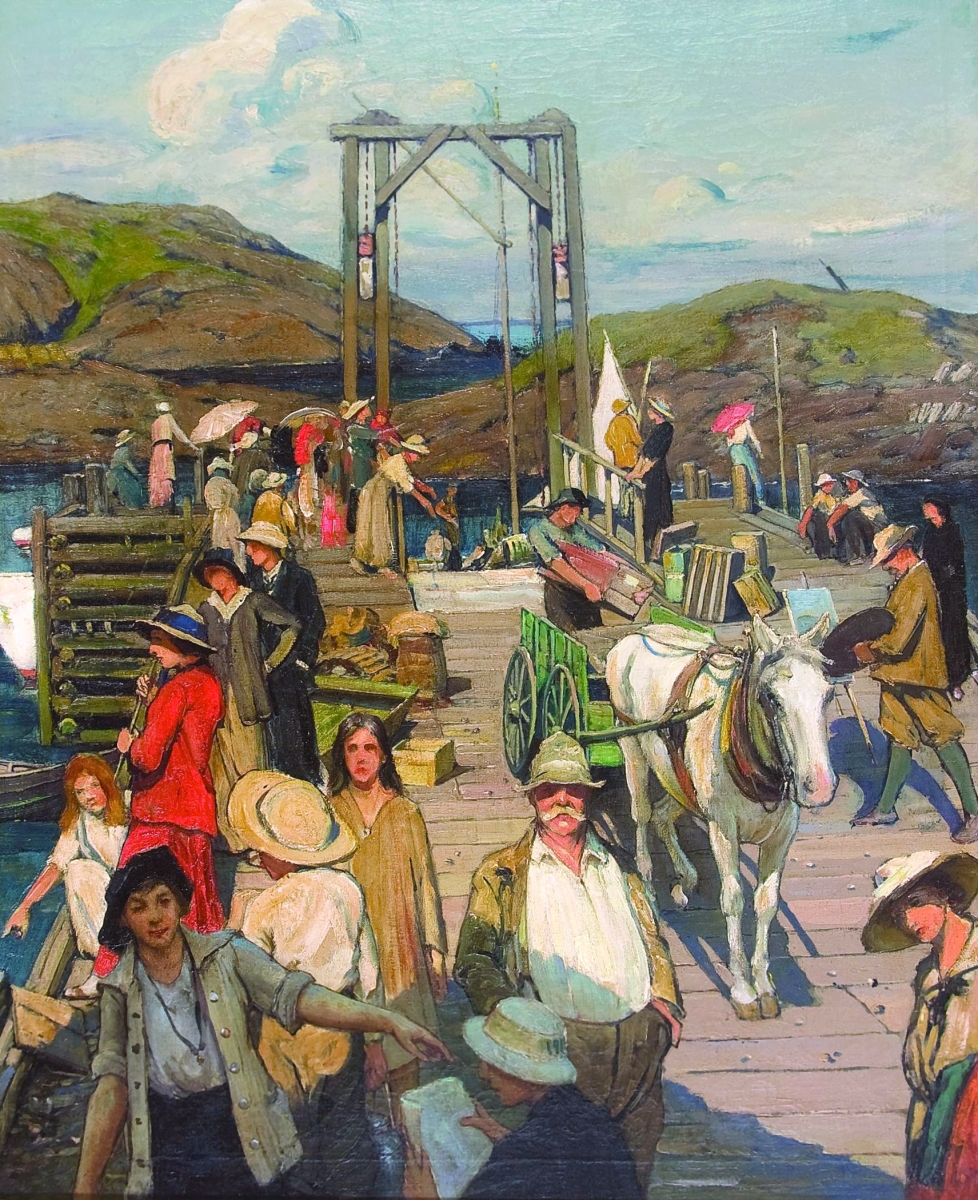

Strisik’s gorgeously painted 1959 view of the ferry dock is a fitting pendant to the 1916 work by Robert Van Vorst Sewell that opens the first part of the show. While Strisik envisions a quiet time between boats, Sewell’s work shows a ferry disembarking with all the attendant hustle and bustle. Nevertheless, the two paintings together show how little things had changed over the more than 40 years that separate them. And indeed, little has changed today. People still wear those straw hats. Helpers still wait to carry bags to the hotels (although they now have pickup trucks rather than horse carts). And artists are still perched everywhere; their easels set to capture the view.

Strisik is one of several artists whose Monhegan experience bridged the pre- and postwar years. Kent and Nevelson are others, and still another is James Fitzgerald, whose thickly impastoed “Gulls Descending” is on view in the first part of the exhibition, in the assistant keeper’s house, even though it was painted in 1966 and is thus considerably later than most of the other works displayed in that space. Perhaps this was done to keep Fitzgerald near Kent, for the two artists shared a history that is another crucial part of the Monhegan Museum’s story in this anniversary year.

Rockwell Kent was only 23 when, in 1905, along with Bellows, Edward Hopper, Leon Kroll and several other students of Robert Henri, he visited Monhegan for the first time. “He just fell in love,” says Stahl. After just one summer, Kent decided to make Monhegan his year-round home. Though many must have doubted this New Yorker’s ability to weather an island winter, he proved equal to the challenge, finishing construction of his two-room cottage himself after growing frustrated with the pace of the man he had hired to do it (a brief essay in the catalog by Jim O’Gorman delineates Kent’s little-known background as a student of architecture as well as art). “It’s very utilitarian; it’s very New England,” says Stahl, standing at the home’s unaltered front door. “Those values were important to him. And it’s beautifully built.”

The tiny house was where Kent painted masterpieces like “Winter, Monhegan Island” (Metropolitan Museum of Art) and “Toilers of the Sea” (New Britain Museum of American Art), both 1907. Within a few years he added a separate studio, with an eye toward establishing a summer art school there. That building, completed in 1910, also still stands, just a short walk away through an overgrown path. Both the house and studio have windows facing the harbor, so visitors to the island today can take in more or less the same view that is depicted in Kent’s “Village at Night,” on view at the museum. Both buildings are filled with personal artifacts: the piano and Victorian sofa that were wedding presents in 1908, the rocking chair that Kent made himself and the plaster Luca della Robbia knockoffs that Kent incorporated into the brick fireplaces.

“Monhegan Pier” by Paul Strisik (1918–1998), 1959, oil on canvas, 24 by 30 inches. Gift of Nancy Strisik, 2002.

But the buildings bear the mark of another artist, too: James Fitzgerald. The story is complicated and circular, but in a nutshell, Kent and Fitzgerald, both veteran Monhegan painters, only came to know each other in 1948, after Fitzgerald had been painting there for 24 years and Kent had just returned from a 31-year hiatus. Through a series of complex transactions, Kent repurchased his 1906 cottage, long in other hands, and Fitzgerald came to own Kent’s 1910 studio, just a stone’s throw away. They lived as neighbors and colleagues for some time before Kent wore out his welcome on the island, attributable not only to his socialist politics but also to whispers surrounding the mysterious death of a houseguest in 1953 (there is no evidence that Kent or his wife was responsible). The Kents fled the island that year, never to return, though they maintained a close correspondence with the sympathetic Fitzgerald. When they made the decision to sell their beloved home in 1958, it went to him. Fitzgerald lived and worked there until the autumn of 1970, when he took an extended painting trip, fully intending to return in the warmer weather to complete the canvas that now hangs, bare, over the studio’s front door. He died on the island of Arranmore, off Donegal, Ireland, in early 1971; Kent died of a heart attack later that year.

Thanks to Fitzgerald’s patron Anne Hubert, who inherited the properties from Fitzgerald, the house and studio remained faithfully preserved, and since 2003 they have belonged to the Monhegan Museum. This anniversary year has seen the Kent-Fitzgerald House and Studio accepted into the National Trust’s Historic Artists’ Homes and Studios program, a prestigious club with only 36-member institutions-a truly transformative moment for the museum and the island. Also this year, Monhegan artist and museum supporter Jamie Wyeth – son of Andrew and grandson of N.C. – has also just announced his intention to leave the museum his superlative collection of works by Rockwell Kent in his will, a promise that comes with a $1 million challenge grant to support the museum’s endowment. Indeed, the Monhegan Museum has much to celebrate in its 50th year.

Life on a Maine island can have its limitations. But Monhegan’s artists – as well as its indefatigable museum – offer compelling evidence that art is the matrix through which such limitations can become liberating. After 160 years, the island remains a hotbed of artistic activity, with new material patiently waiting in line for the museum’s inevitable centenary exhibition in 2068.

The Monhegan Museum is at 1 Lighthouse Hill. For information, 207-596-7003 or www.monheganmuseum.org.

Jessica Skwire Routhier is managing editor of Panorama , the journal of the Association of Historians of American Art. She lives in South Portland, Maine