Teapot and sugar bowl manufactured under the “Rieti” line at the New England Pottery Company in East Boston, Mass. These were reportedly found together years ago in an old estate in Chicago.

By Justin W. Thomas

The Chelsea Keramic Art Works is one of the first American ceramics firms to designate itself as an art pottery company. Located just north of Boston in Chelsea, Mass., the company was established by the Robertson family in 1866, all of whom had been employed in the ceramic industry in England before working in Chelsea. Although Hugh Robertson (1844-1908) was the true force behind the company’s success (and later the Dedham Pottery in Dedham, Mass.), creating a variety of earthenware that was inspired from classic designs, as well as styles that were in line with English production of the period. Wares made by this company can be found in art museums all over the United States, such as the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in Manhattan and the National Museum of American History at the Smithsonian Institute in Washington DC, among other museums.

Today, however, it is less well known that the New England Pottery Company was likely just as prominent, operating during the same time, only a few miles away in East Boston, Mass. Frederick Meagher originally established the company in 1854, manufacturing an assortment of household yellow and Rockingham glazed ware; however, in 1876, Thomas Gray and Lyman W. Clark, son of Decius W. Clark of Bennington, Vt., bought the East Boston business and established the New England Pottery Company.

Clark had much useful experience in preparing clays and glazes while at Bennington, then for a short time at Kaolin, S.C., and later at Peoria, Ill. The first wares made under his direction at East Boston were of a utilitarian nature. From the company’s advertisements, we learn that white granite and common crockery, table and toilet ware were the sole output.

Of all the goods produced at this company, it is notable that from 1886 to 1895, Thomas H. Copeland of the famous English potting family modeled most of the pieces. J.W. Phillips originated many of the designs used in the printing process, although many were also hand decorated, with Doulton and Royal Worcester wares the inspiration sources.

Copeland is responsible for creating some of the company’s best shapes and decorations, one of which being a bold blue glaze ornamented with gold. Some of the decorations introduced by Copeland were considered advanced for American manufacturers. Copeland also helped sell the goods.

Pitcher manufactured at the New England Pottery Company in East Boston, Mass., displayed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in Manhattan. Photo courtesy the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

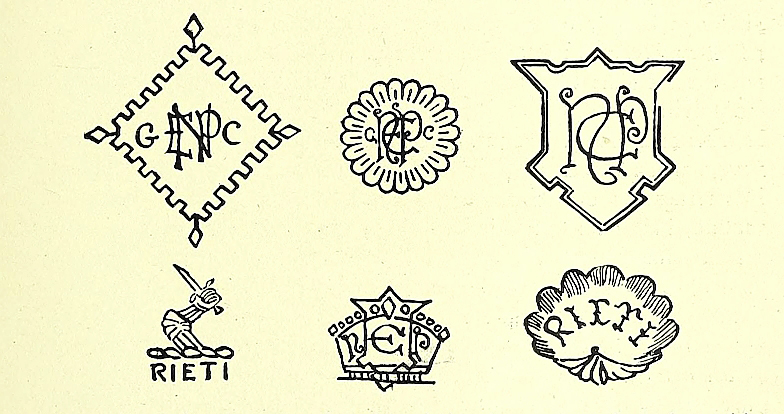

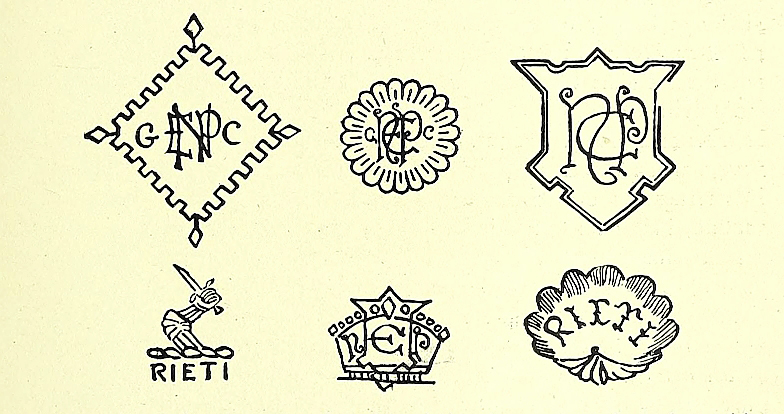

American archaeologist and author Edwin Atlee Barber (1851-1916) wrote extensively about the New England Pottery company when Marks of American Potters was published in Philadelphia in 1904, documenting all of the company’s different marks based on his personal relationship with Lyman W. Clark. According to Barber, “The first mark employed by the company was the great Seal or Arms of the State of Massachusetts, which was used from 1878 to 1883 on ironstone china or white granite ware.

“A special order of goods for a private purchaser was marked with a flying eagle. This was printed in black beneath the glaze. A lozenge-shaped device with meander bordering, enclosing the monogram of the name of the company and initials of the proprietors, was used on stone china from 1883 to 1886. Cream-colored ware was marked in black with a similar design and a scalloped, circular outline, during the years 1886 to 1892, when its manufacture was discontinued. In 1886, the firm began to make a semi-porcelain ware in colored bodies, which was decorated in an artistic manner. To this product, they gave the name of “Rieti” ware. This was first marked in black beneath the glaze, with a mailed hand holding a dagger. The design was changed in 1888, and from then until 1889, the “Rieti” mark was a shell bearing the name, also printed in black beneath the glaze. From 1889 to 1895, when the production of “Rieti” ware was abandoned, the mark was a crown and shield combined, printed on the glaze in red. The last mark, used on special articles and shapes, in “Paris White” ware, was adopted in 1897.”

Undoubtedly, the most notable and aesthetically appealing wares made in East Boston were those manufactured under the “Rieti” line. These types of products are found in museums around the United States today, including the National Museum of American History at the Smithsonian Institute, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Philadelphia Museum of Art and Historic New England. These objects were often hand decorated in ornate gold designs, as well as a variety of other decorative techniques.

The documented East Boston forms include vases, pitchers, chocolate pots, teapots, sugar bowls, oyster plates, cracker jars, vegetable dishes, sauceboats, water pitchers and basins, ginger jars, mugs, potpourri jars and other shapes as well.

Various marks used by the New England Pottery Company in East Boston, Mass. Source: Marks of New England Potters by Edwin Atlee Barber, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Patterson and White Company, 1904.

Interestingly, housed in Historic New England’s storage facility in Haverhill, Mass., is a group of large semi-porcelain flat salesman’s samples from the “Rieti” line, which the company’s agents carried around to show to prospective clients. These are the only surviving examples like this currently known to exist today and they are a lot larger than the actual products. Historic New England owns in its photographic collection stock photos of the New England Pottery Company product lines that were gifted to the museum in 1931.

Although, the origin of the name “Rieti” is a mystery today, it may have something to do with the reproduction of ancient Greek pottery, seeing as it was a popular style with pottery manufacturers in the Boston area at the time; the product line may have been named after Rieti, an ancient town in central Italy.

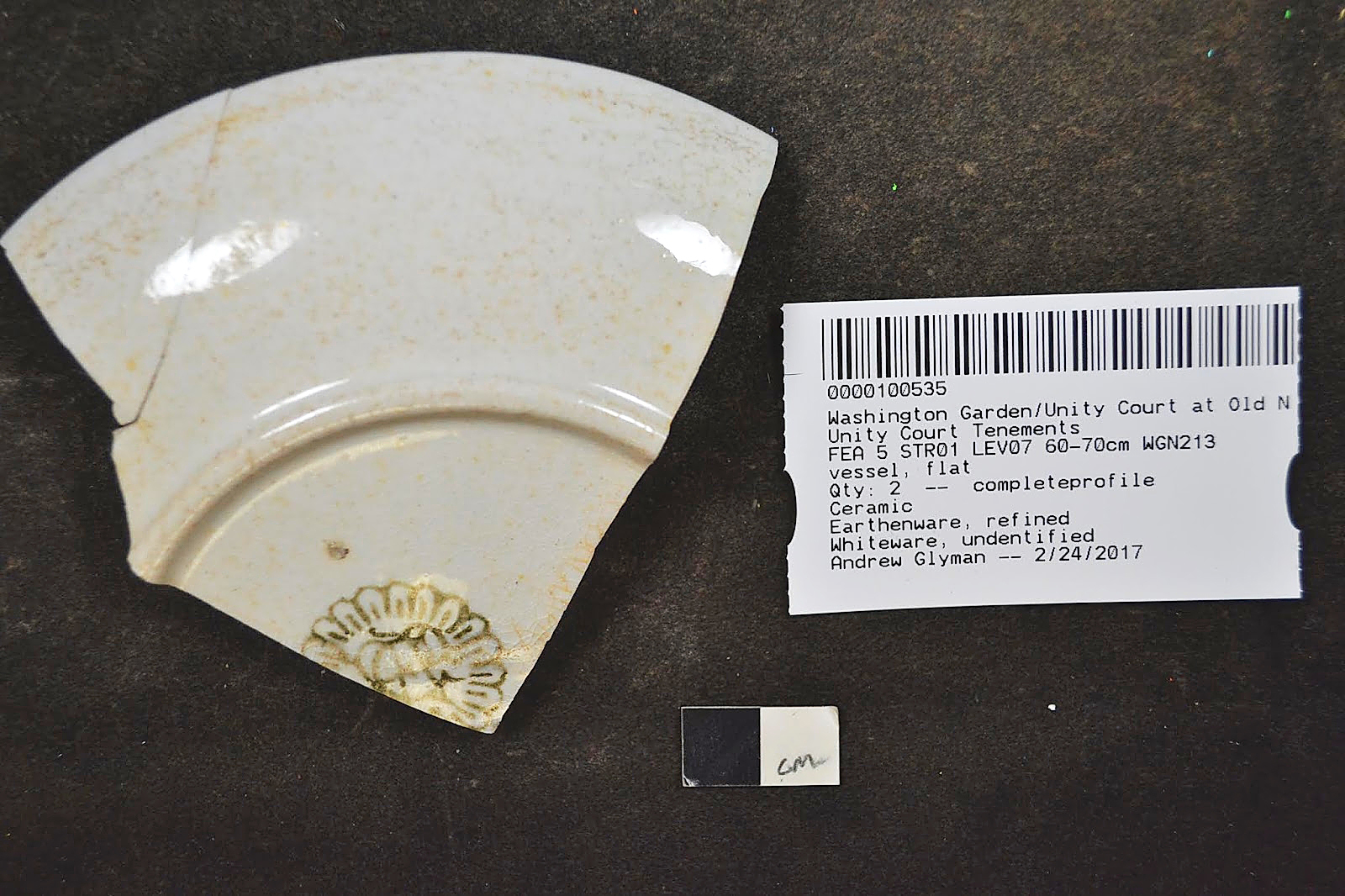

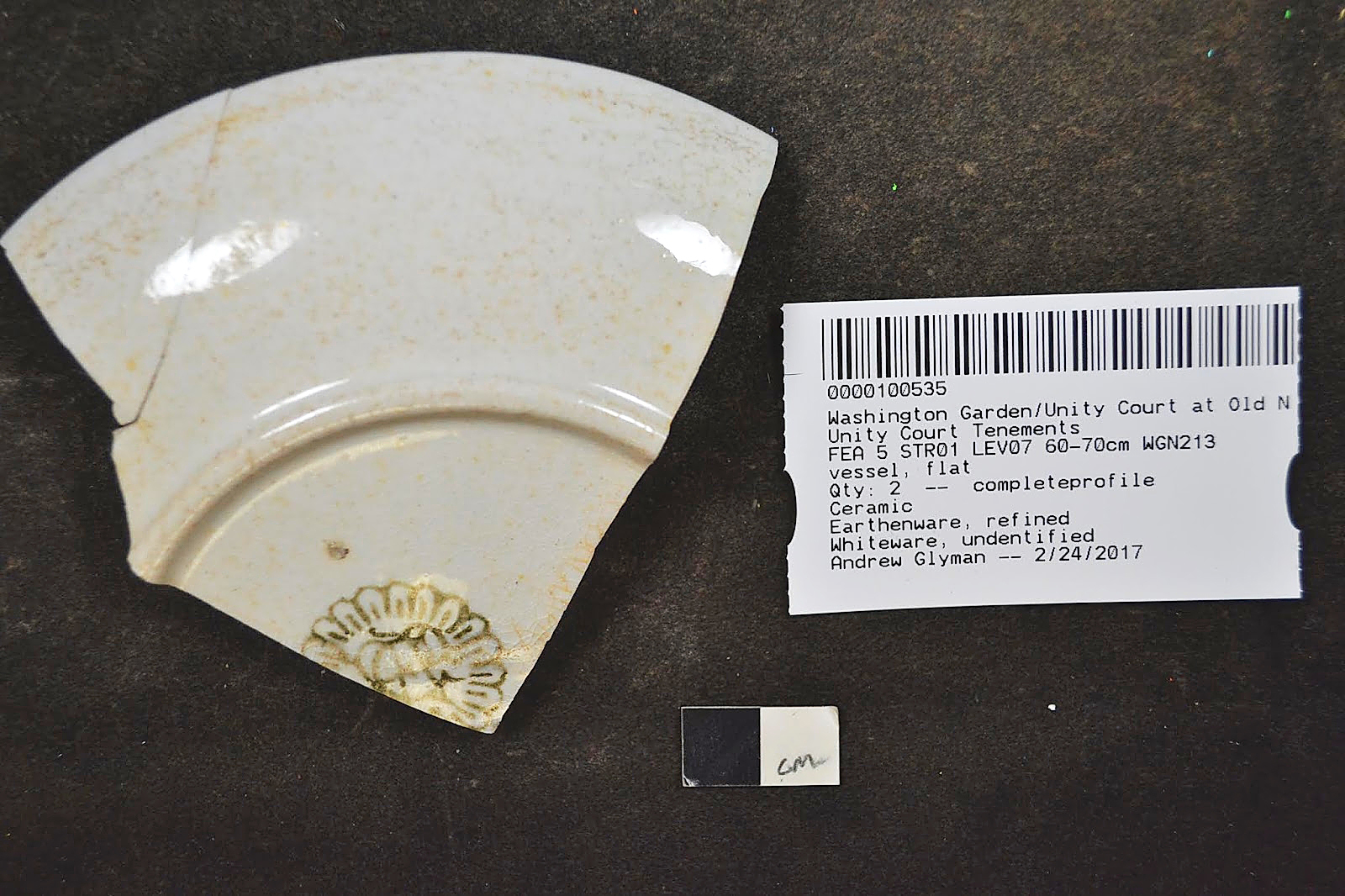

The most significant archaeological artifact from this company is perhaps the remains of a dish recovered a few years ago by Boston City archaeologist Joe Bagley, as part of an archaeological dig at Washington Garden at the Old North Church in Boston’s North End neighborhood. Bagley’s research with historical records leading up to the dig found that Washington Garden was the previous location of two Nineteenth Century tenement buildings and their outhouses or privies.

Remains of a circa 1880 dish manufactured at the New England Pottery Company in East Boston, Mass., which was recovered from Washington Garden at the Old North Church in Boston’s North End neighborhood. Photo courtesy City of Boston Archaeology Program.

The recovered white granite sherd represents the remains of a dish; based on the mark, it was manufactured at the New England Pottery Company about 1880, which would have included it with the first line of wares produced by Thomas Gray and Lyman W. Clark in East Boston after 1876.

The New England Pottery Company is a business that deserves more attention today, especially its “Rieti” line and the wares that were manufactured during Thomas H. Copeland’s years of employment. Copeland left the company in 1895 when the “Rieti” line was abandoned.

New England Pottery was a significant Boston business. Even though much of its production was molded, the best pieces were beautifully hand decorated in bold colors, some of which have gained the attention of major museums. Unlike anything else manufactured in the Boston area, the best pieces were likely also shipped to other major American cities and should be included when considering the best pottery manufacturers in the Boston area during the late Nineteenth and early Twentieth Century.