“Saul and the Witch of Endor” by William Sidney Mount, 1828, oil on canvas. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC, gift of International Business Machines Corporation.

By Z.G. Burnett

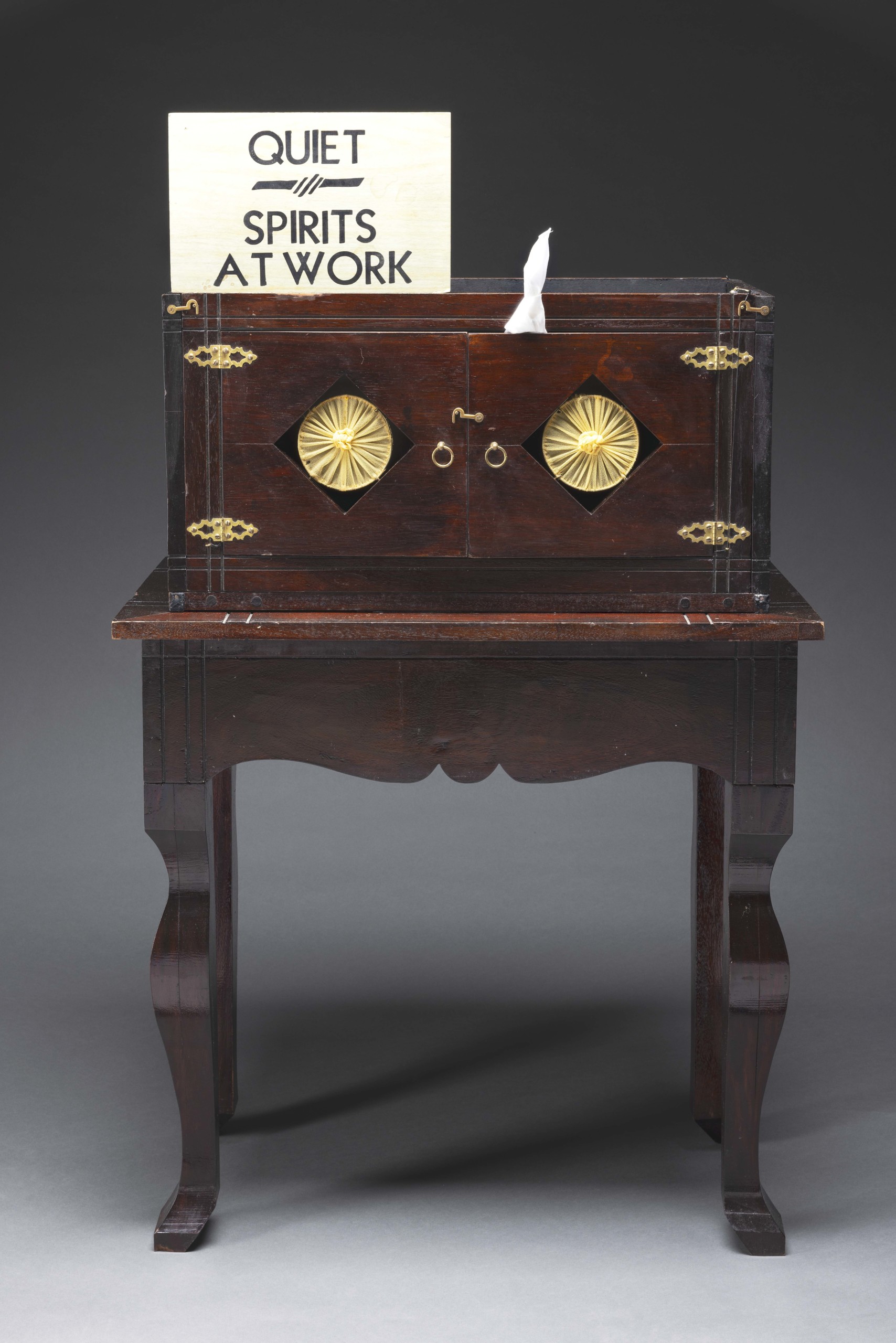

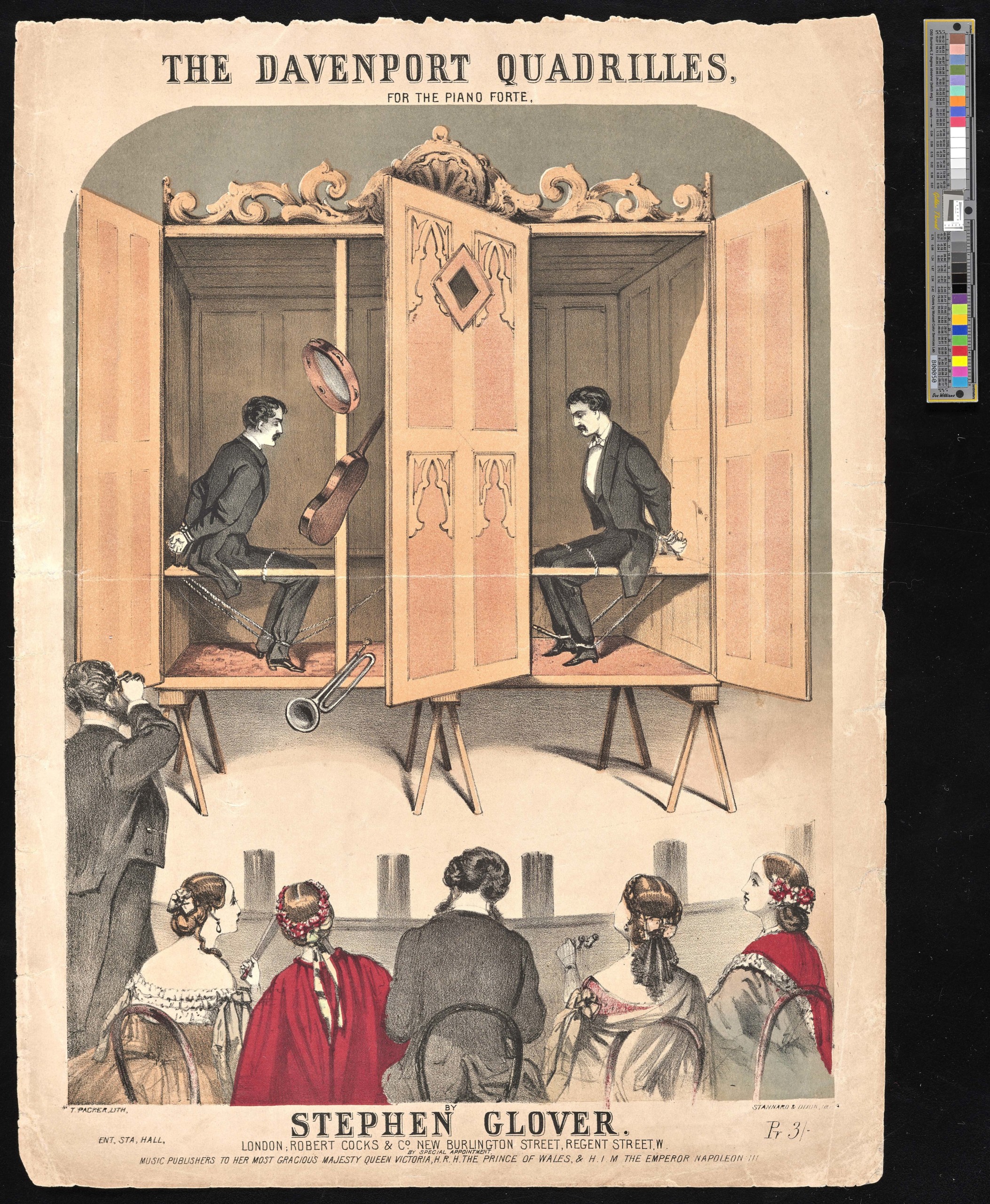

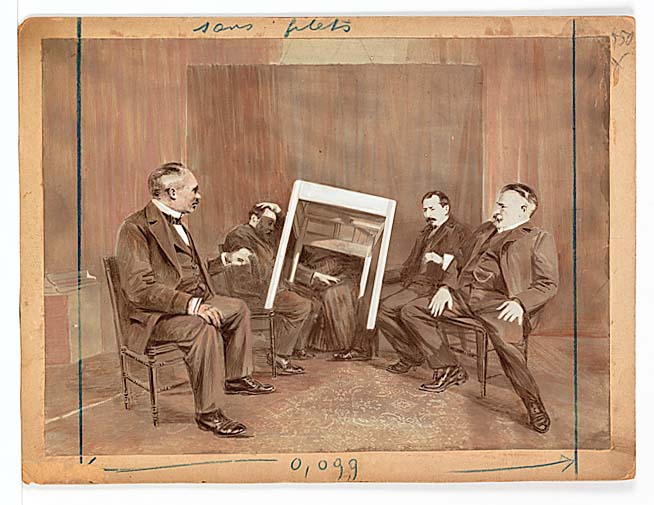

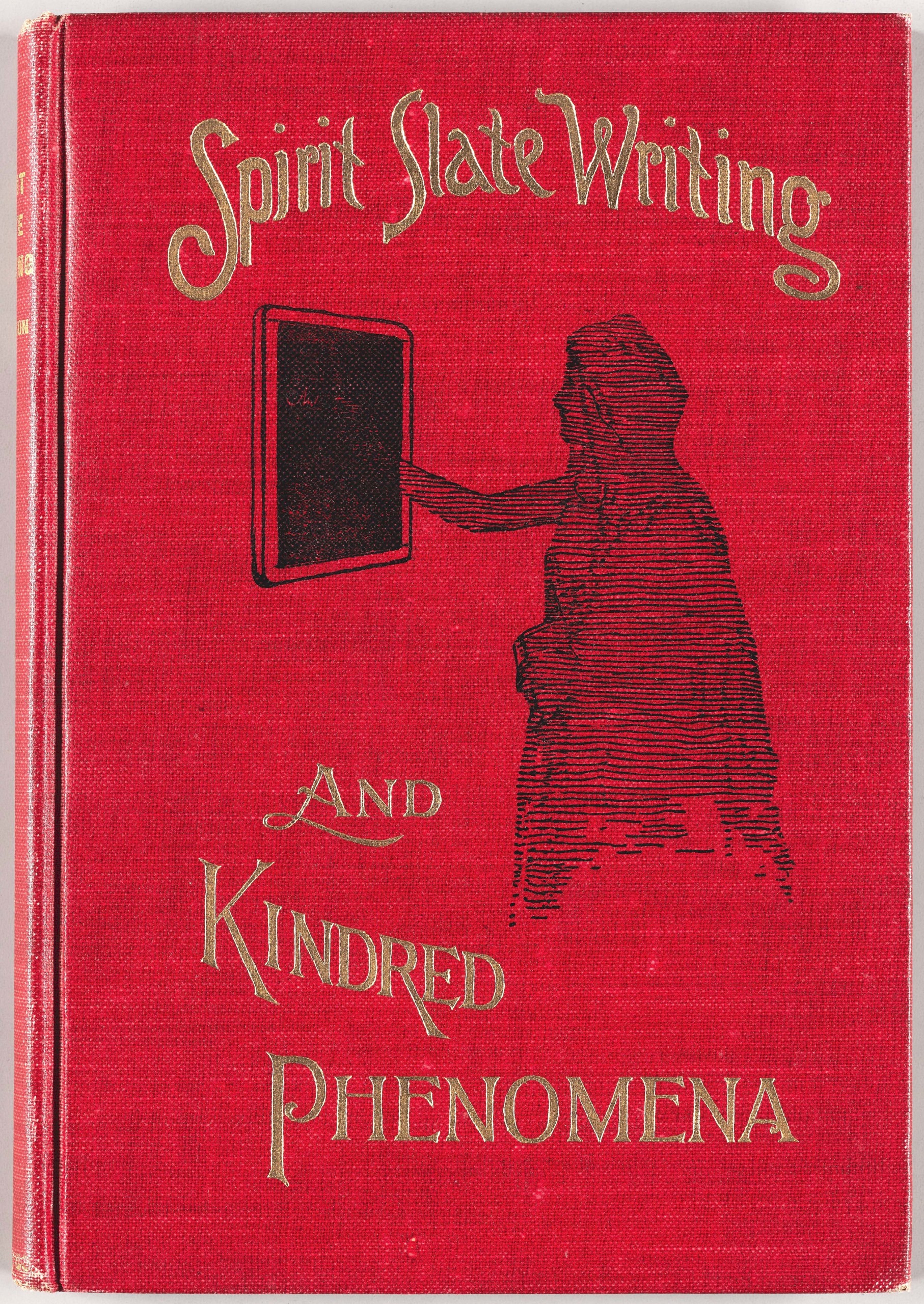

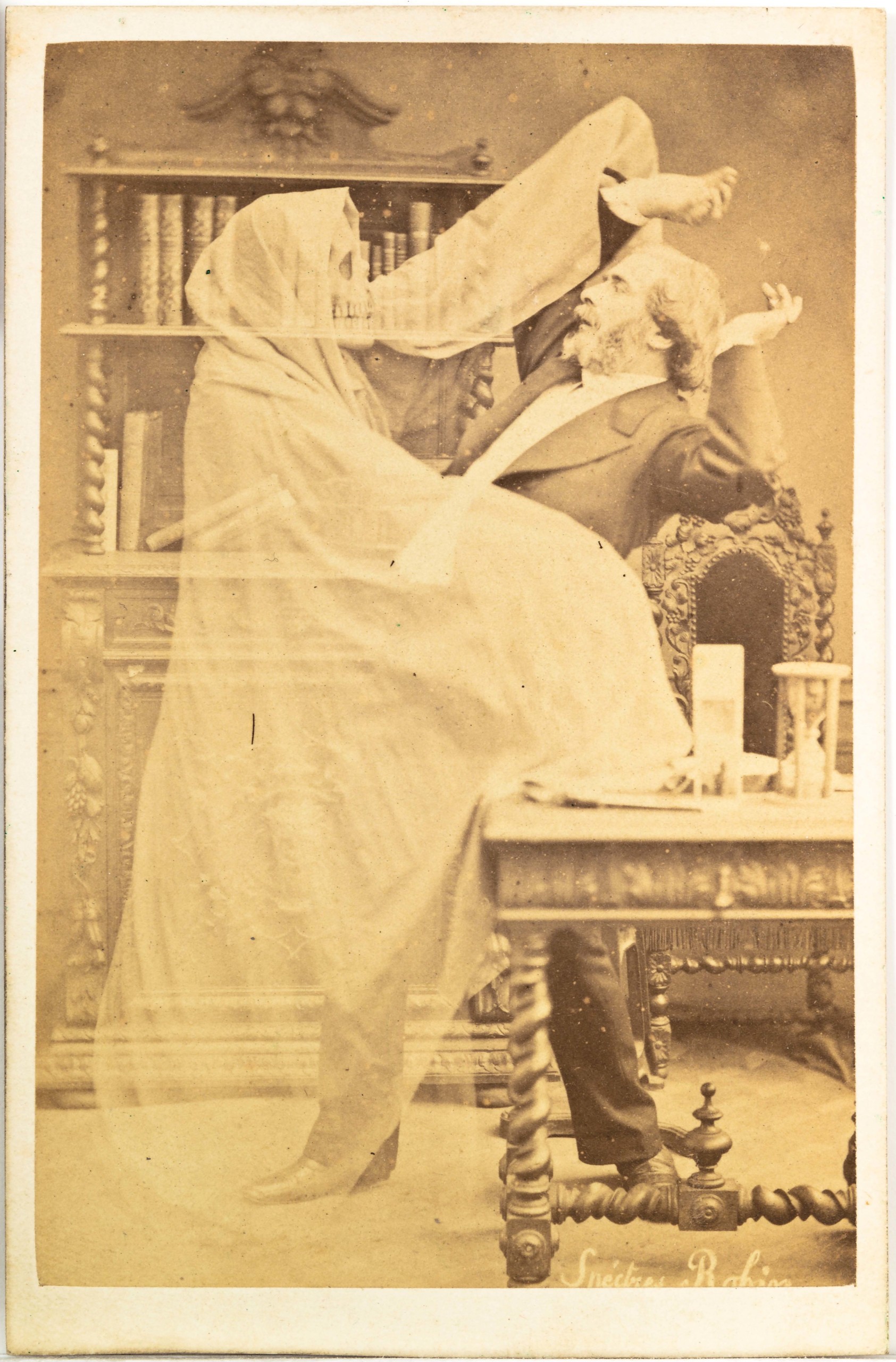

SALEM, MASS. — Is there life after death? Does magic exist? Or do we simply want to believe? During the mid Nineteenth Century to early Twentieth Century, these timeless questions experienced an explosion of interest that grew alongside the rise of popular technology. As media such as early photography and electricity developed, those claiming to be mediums between the living and the dead used both methods and much more to prove the validity of their abilities. Skeptics and critics did the same, employing the same tools to expose those who took advantage of mourning customers desperate to make contact with their lost loved ones. The Peabody Essex Museum (PEM) explores this enchanting era through paintings, posters, photographs, stage apparatuses, costumes, film, publications and other objects with its new exhibition “Conjuring the Spirit World: Art, Magic and Mediums,” opening on September 14.

“Each of these objects is a work of art integral to this story,” said George Schwartz, curator-at-large. “[This exhibition] peels back the layers of the European and American interest of Spiritualism and its performance.” The rise of Spiritualism, as a movement and “social, quasi-religious belief system,” occurred during an age when the study of what was “natural” and “unnatural” increasingly became a subject of public discussion. What spiritualists claimed to contribute was a “supernatural” option, capturing the same public’s imagination.

Despite major advancements in medical science and technology, European and American mortality rates remained high throughout the Nineteenth Century. People were better acquainted with the realities of death during this time and physical contact with the dead was not unusual. Bathing, dressing and showing a corpse was considered a family responsibility, and was also a practical way of processing grief.

“Photograph of Mrs Lincoln with spirit of Abraham Lincoln and Son” by William H. Mumler, 1872, albumen print. Collection of Tony Oursler. Photo courtesy of Oursler Studio.

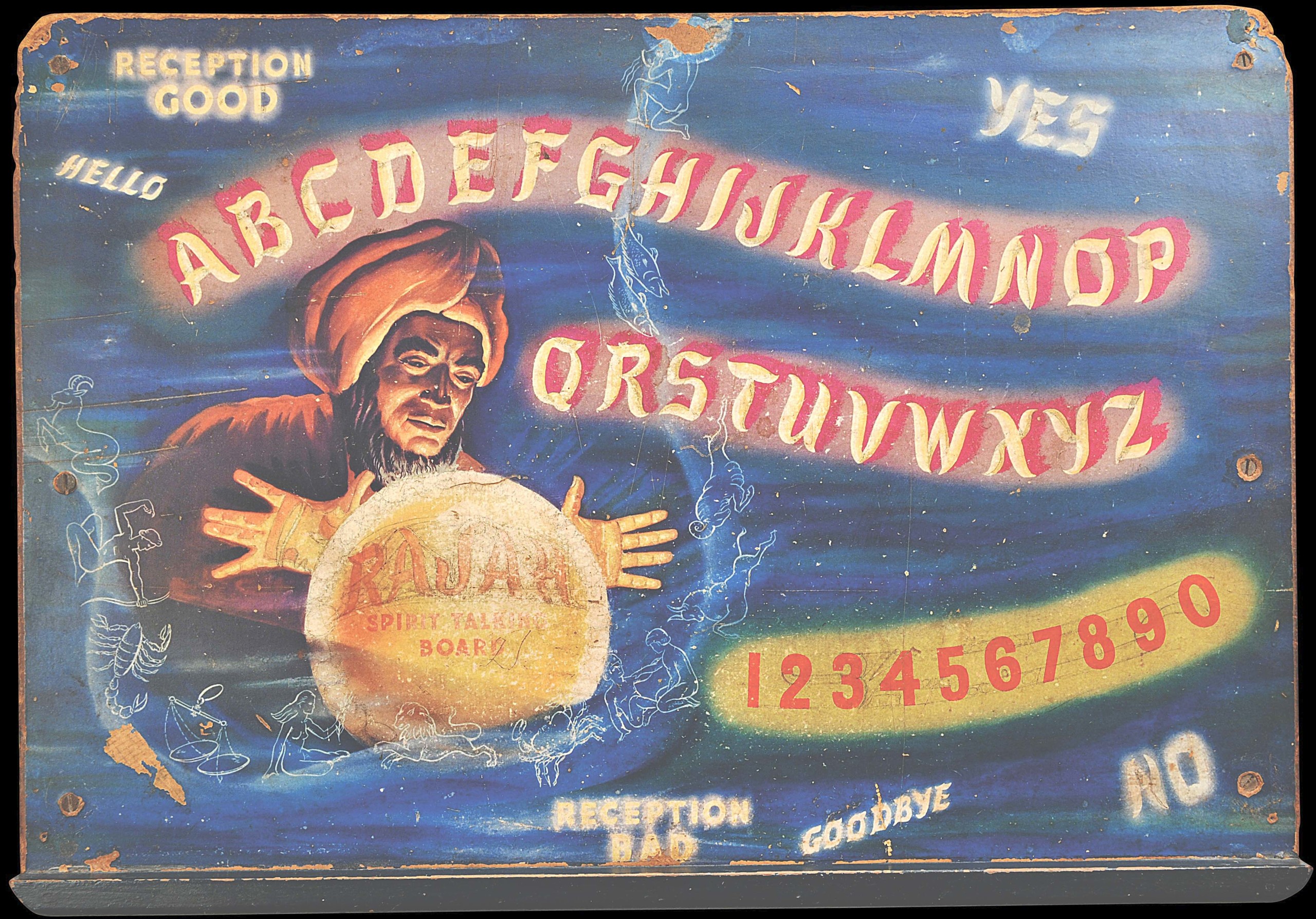

This era in particular produced a robust material culture of mourning, including jewelry and decorative arts containing loved ones’ hair, posthumous portraits and later postmortem photographs and death masks. The emotional power that these relics provoked became fuel for the rise of the Spiritualist movement, which in turn relied on objects and contraptions to allegedly make contact with the dead.

Although the first known usage of the word spiritualism is attributed to the Swedish theologian Emanuel Swedenborg (1688-1772) in the late Eighteenth Century, “modern” Spiritualism in the United States gained notoriety in upstate New York during the 1840s. The infamous Fox sisters, Kate and Margaret, created a sensation with their seances during which the spirit would communicate with rapping sounds.

As the years progressed and Spiritualist practices came under closer scrutiny, the Fox sisters admitted in 1888 that the seances were a hoax, creating the sound themselves through various means such as cracking their toes. They then recanted their admission, but the damage was done and skeptics were further emboldened.

Kate and Maggie Fox, spirit mediums from Rochester, N.Y. Daguerreotype by Thomas M. Easterly, 1852. Missouri History Museum Photograph and Prints collection. Easterly Daguerreotype Collection.

Aside from illness and accidents, armed conflict was a constant headline and cause of death in the Nineteenth Century. The massive loss of life during the American Civil War (1861-65) fractured families on a scale not previously experienced by the young republic. Collective shock settled over American society with many lacking closure. While early embalming was being practiced to return bodies home with minimized corruption, it was by no means the norm it is today. Those who could not say goodbye in person sought comfort from beyond, a service that a growing number of Spiritualist mediums claimed to offer. This included former First Lady Mary Todd Lincoln (1818-1882) who had lost three of her four sons in addition to her presidential husband and participated in seances to speak with them. Such acceptance of these practices propelled Spiritualism in popular imagination, creating a culture of study and skepticism that continued after the devastation of World War I (1914-1918).

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930), who created the character Sherlock Holmes, was one of the spiritualist community’s first prominent supporters. Straddling the line between natural and supernatural research, Doyle was a practicing medical physician as well as a Freemason and member of London’s Society for Psychical Research. “This interest seeped into fiction, then nonfiction about spiritualism and spiritualist photography,” said Schwartz, a lifelong Sherlock Holmes fan, adding that Doyle had his own collection of alleged spirit photography housed in his own Psychic Museum and bookshop. His drive to make contact with “the other side” was strengthened by his son’s death in 1918, following medical complications after combat in the Battle of the Somme.

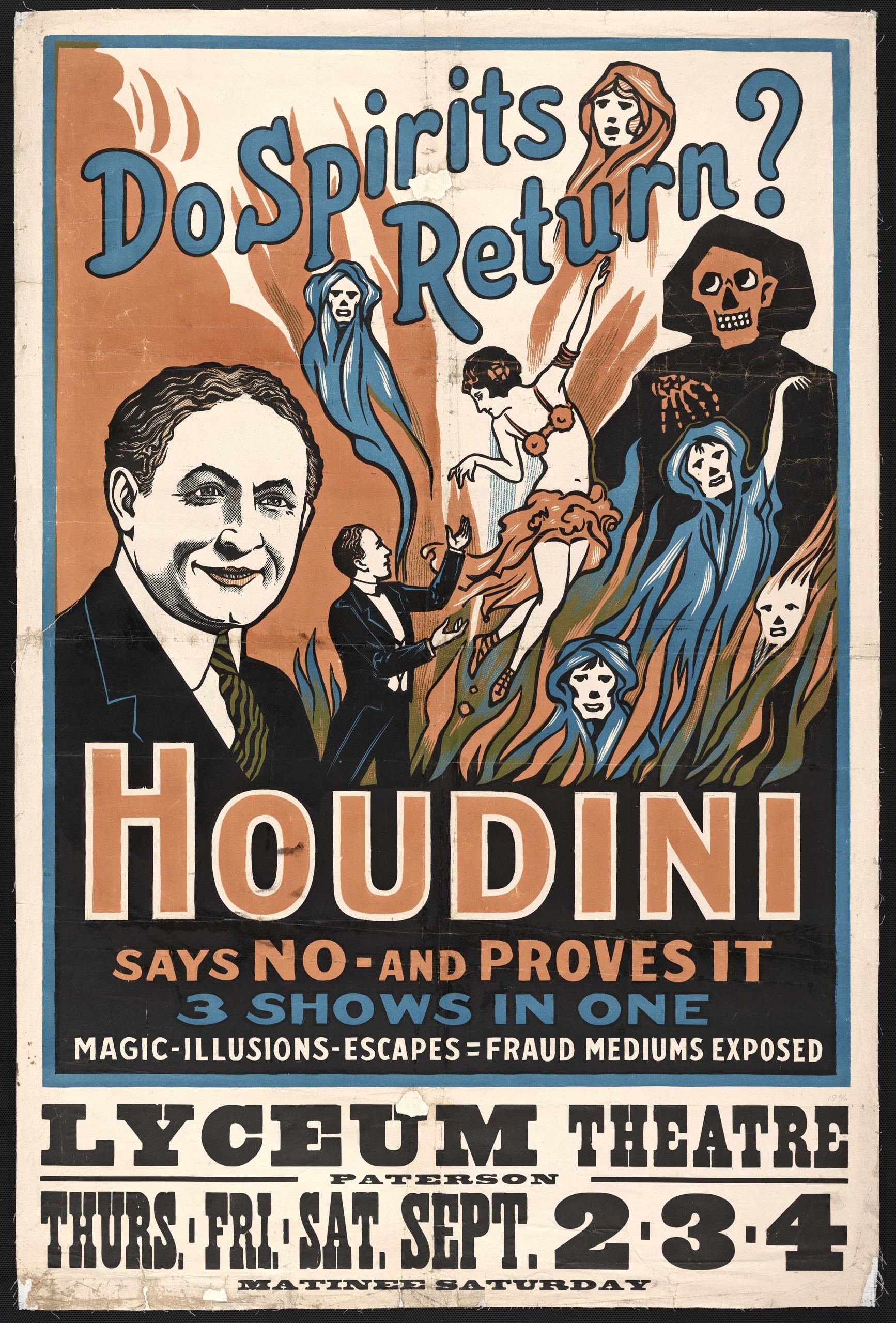

“Do spirits return?,” American School, 1926, lithograph. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

Another enthusiast was the celebrated escape artist Harry Houdini (1874-1926), who was friends with Doyle for a time despite Houdini’s ardent anti-spiritualist stance. Along with his fame on the stage, Houdini made it his mission to debunk mediums who claimed to contact and summon the dead after a hired seance failed to contact his late mother. After their first meeting at one of his private performances, he even had to convince Doyle that his illusions were nowhere near supernatural. Their professional disagreements eventually turned into a bitter falling out, and Doyle spurred the magazine Scientific American to create a contest with a grand prize of $2,500 (about $46,000 in 2024) for any medium able to produce physical manifestations of spirit communication. Houdini was one of the group’s main investigators, and even attended congressional hearings to disprove celebrity mediums as merely talented performers.

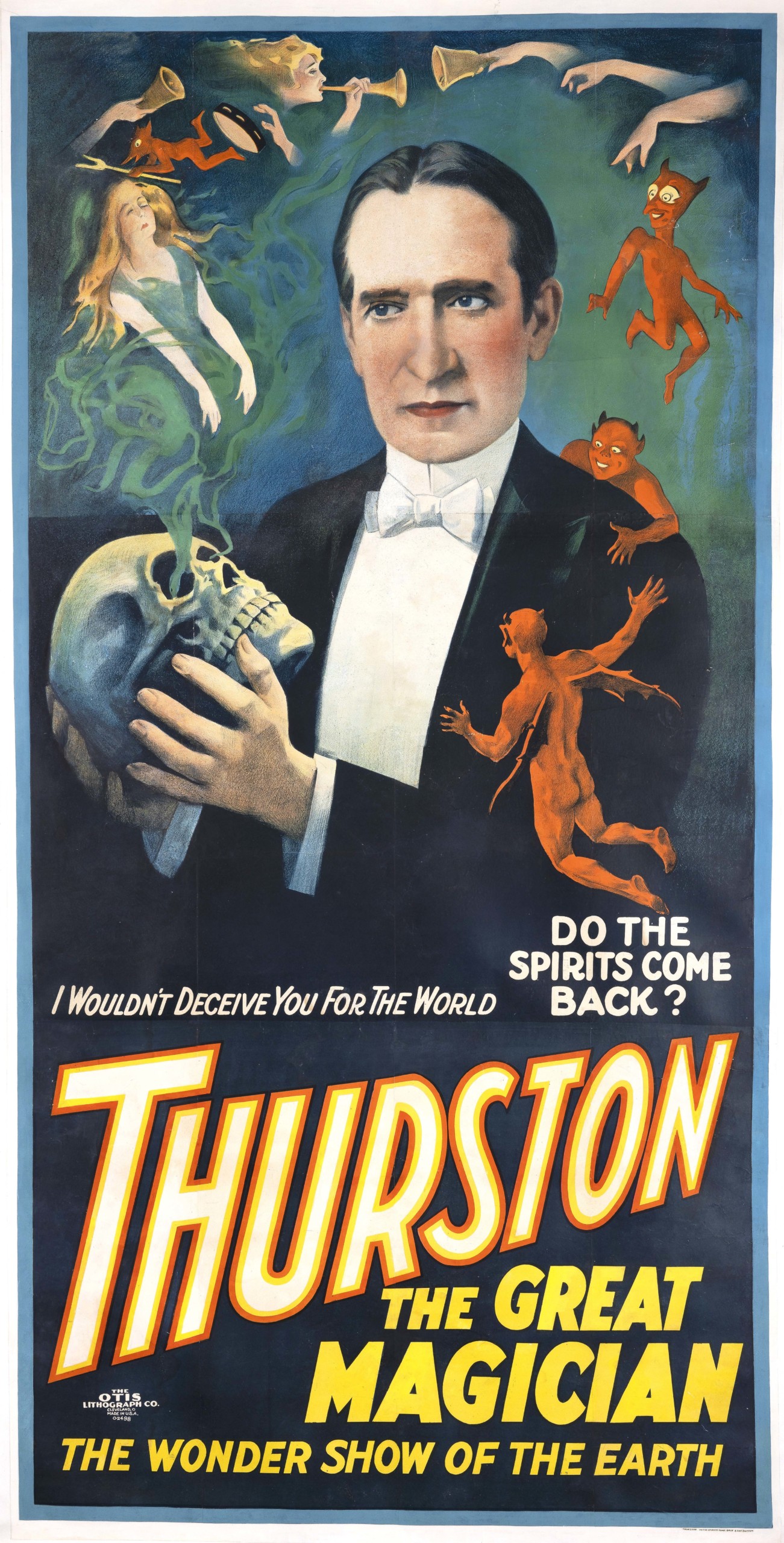

Mediumship and magic occupied a nebulous shared space, with many of its participants claiming to be one or the other in the span of their careers. Mystery was their stock in trade, and performers would embrace the supernatural at the same time they were denouncing it. When asked about his favorite object in the exhibition, Schwartz answered, “One standout piece is the three-sheet poster of Howard Thurston, a contemporary and rival of Harry Houdini.” Thurston had been using Spiritualist techniques in his act for a decade, carefully cloaking his personal life and past to foster ambiguity in his public persona.

“Thurston The Great Magician,” The Otis Lithograph Company, Cleveland, 1929, lithograph. Museum purchase. Peabody Essex Museum.

“It’s a visual and textual ensemble that would have been familiar to viewers, it encapsulates the iconography [of this business],” Schwartz continued. “A skull reminiscent of Hamlet, green smoke, ghosts, disembodied limbs holding instruments, imps…” This symbology is also familiar to contemporary viewers, especially those with a penchant for the macabre. Even today, people still seek answers about life after death, and even beyond that frame of understanding. The poster’s bold proclamations echo in paranormal study and entertainment, still garnering public fascination, “I would not deceive you for the world; do spirits come back?” Come decide for yourself at PEM’s “Conjuring the Spirit World.”

The Peabody Essex Museum is at 161 Essex Street. “Conjuring the Spirit World: Art, Magic and Mediums” is on view from September 14 to February 2. For additional information, 978-745-9500 or www.pem.org.