By Kristin Nord

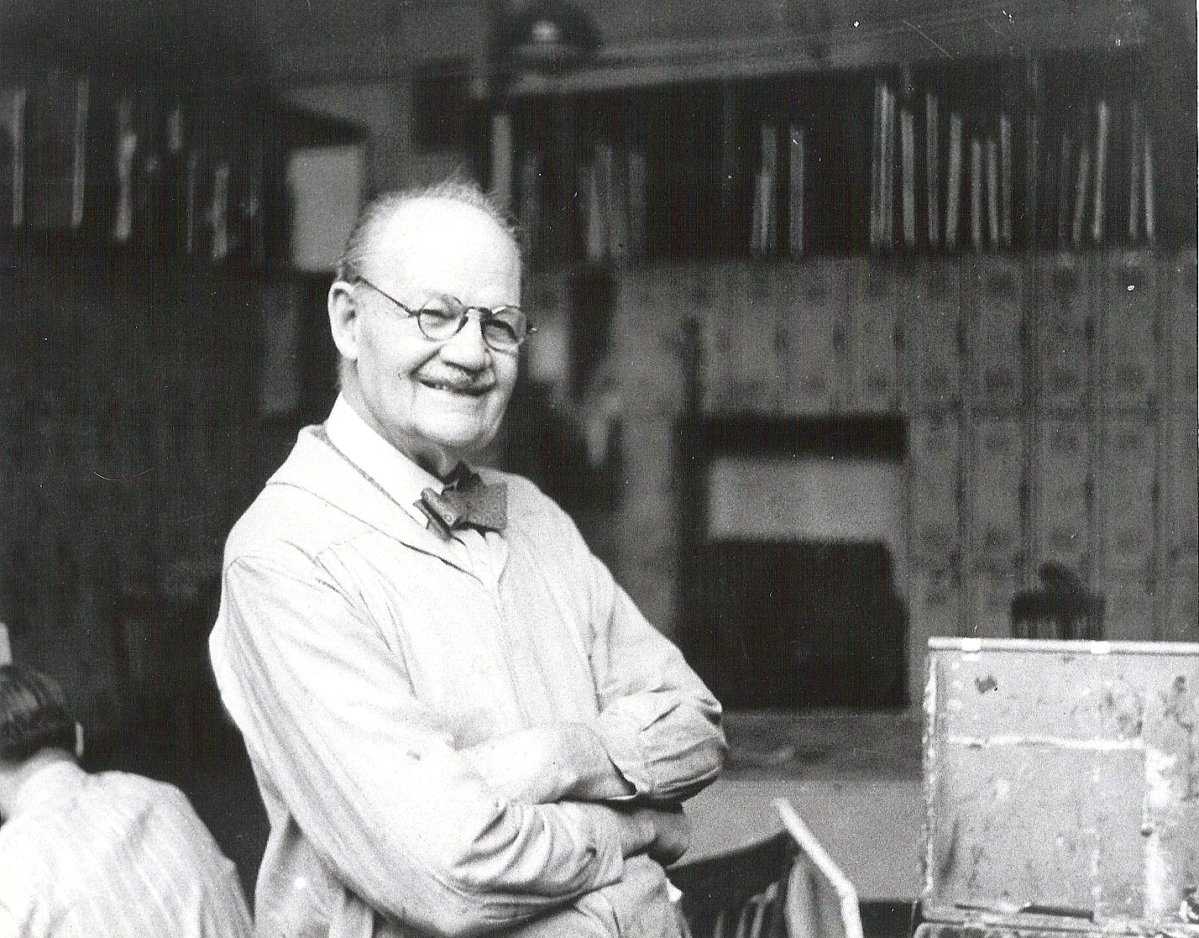

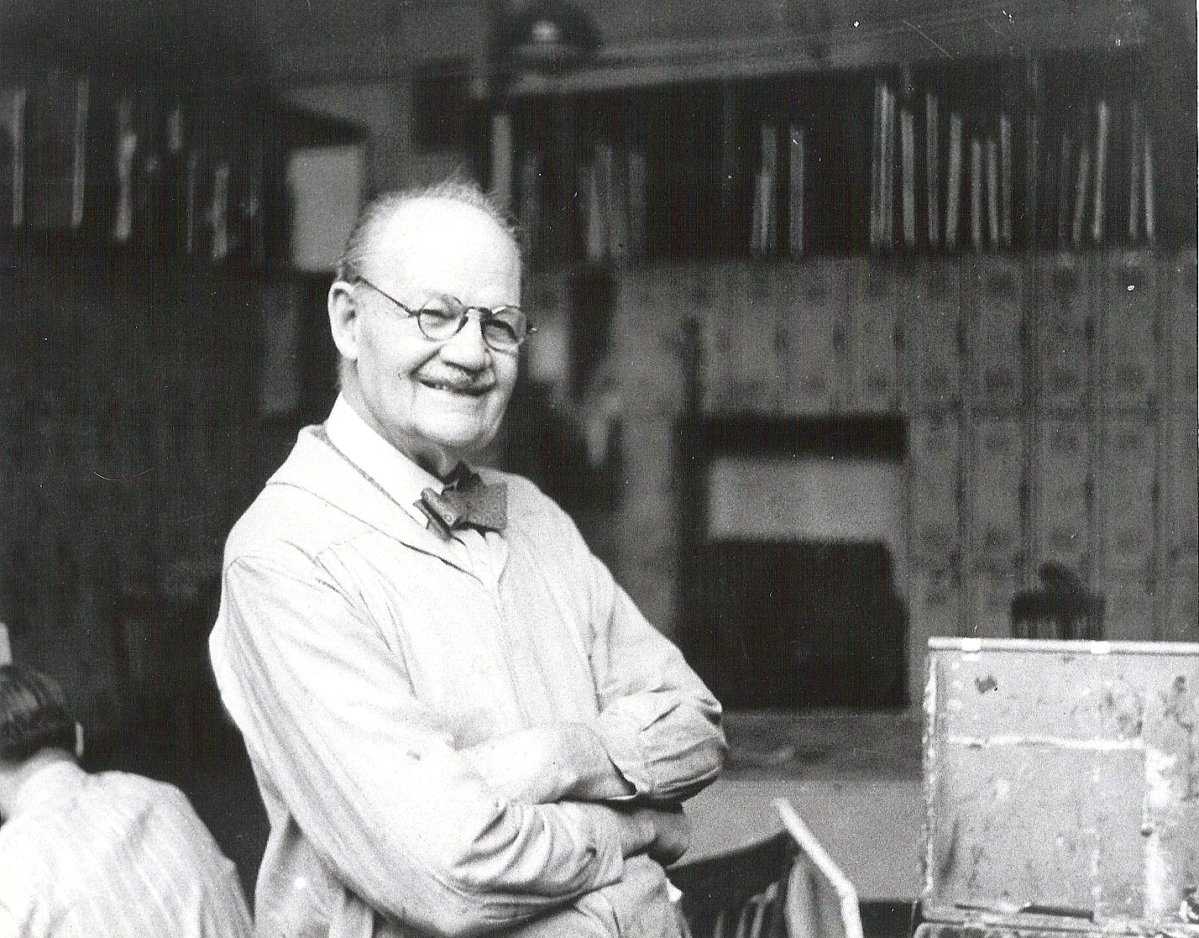

NEW LONDON, CONN. – By some accounts, Frank Vincent DuMond (1865-1951) is perhaps the most important American arts educator of the Twentieth Century, but his talents have resided largely under the radar. “The Prismatic Palette: Frank Vincent DuMond and His Students,” however, on view at the Lyman Allyn Art Museum through October 3, will go a long way toward burnishing DuMond’s reputation.

The exhibition, drawn from both public and private collections, and curated by Tanya Pohrt, PhD, reveals DuMond as a gifted young artist who would deploy the lessons he’d garnered in an early professional life to shape his work and philosophy in the classroom.

“Like many artists of his generation,” Jeffrey Andersen, the former director of the Florence Griswold Museum, and author of The Harmony of Nature: The Art and Life of Frank Vincent DuMond, writes, “he was stimulated by the opportunity to work in various media and to work in concert with other artists, artisans and architects, and to the wide variety of assignments he brought impressive credentials: his early experience as a newspaper illustrator, his academic training and its corresponding mastery of figure drawing and his extensive travels abroad.”

“Vermont” by Frank Vincent DuMond (American, 1865-1951), 1941. Oil on canvas. Collection of Andrew Charles DuMond.

The Rochester, N.Y., native had begun his studies in 1884 at the Art Students League in New York City and, later, in Paris at the Académie Julian.

In many ways, his career mirrored that of many talented artists of the late Nineteenth Century. While his history paintings garnered him early acclaim, he would stretch as a painter and an illustrator, and produce art influenced by the ideas of the day. For a number of years he earned his bread and butter as a regular contributor to Harper’s Weekly and The Century Magazine. He also completed extensive illustrations for Mark Twain’s Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc and would design two acclaimed and massive murals to decorate the triumphal arch of the 1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco. These murals, later installed in the San Francisco Library, Pohrt’s wall text notes, were “full of energy and character” and championed the artist’s “narrative skill and compositional sophistication.”

He had married Helen Savier, whom he’d met at the Art Students League of New York, and they spent their early years as a couple in Paris, both husband and wife exhibited history paintings at the Paris Salon. DuMond’s skill at rendering light, texture and color was already apparent, whether in the scenes he painted of the fishing village of Martigues or in still life vignettes.

But strong suggestions of what would become DuMond’s primary creative calling came to the fore in about 1900 when the couple returned to the United States and resumed teaching at the Art Students League. He had begun teaching in 1892, when he was just 27 – by all accounts a kind and modest man with a good sense of humor and an openness to ideas.

“Garden in Lyme” by Frank Vincent DuMond (American, 1865-1951), circa 1930. Oil on canvas. Collection of N. Robert Cestone & Stephen V. DeLange.

Over the next half century he would set a lively pace in Studio 7, conducting three intensive workshops daily, six days a week, and following up with student critiques on Sundays. His classes in life drawing, life painting, portraiture and composition proved wildly popular; as time went on some students would have to wait up to two years to gain admittance.

“In the academic sense,” the portraitist Everett Raymond Kinstler observed, “DuMond was a traditional painter, with a remarkable ability to inspire the heart and stimulate the minds of his students. He believed in experimentation and curiosity – and discipline.” He was also an egalitarian, who lobbied successfully for co-ed classes.

DuMond himself said, “I have never asked my students to take my word for anything. They have to get their knowledge from life itself. All we can do is put our students in touch with the source we go to ourselves. And that source is nature.”

In what became his seasonal calendar, the DuMonds resided and taught in the city during the regular academic school year and departed on en plein air painting expeditions in disparate locales in the summers. Whether in New England, Vermont or Nova Scotia, these trips enabled him to replenish himself as he indulged his passions for fly-fishing and for unspoiled nature, Pohrt said.

The Lyme Art Colony in Connecticut had begun in 1900 with founder Henry Ward Ranger hoping it would become an American Barbizon. But the focus changed to Impressionism with the arrival of Childe Hassam in 1903. Overnight Old Lyme became the largest, best-known Impressionist art colony in the nation. Connecticut’s small size and good rail system made it easy for artists with winter studios in New York City to take up summer residence there. The DuMonds added their names to what would become an illustrious roster in 1902, when DuMond was hired to direct the Art Students League of New York-sponsored Lyme Summer School of Art. He and his wife fell in love with Old Lyme and eventually bought a farm there in the Grassy Hill section of the town. And they set down roots there after the summer school had relocated to Woodstock, N.Y. In subsequent years, DuMond would paint a series of vivid scenes of the property’s rocky outcroppings and its sun-kissed gardens and fields.

If his earlier landscapes in Lyme expressed elements of the French Barbizon school, emphasizing atmosphere and shadow, Pohrt writes, by 1906 his palette and style had shifted; now his paintings were deeply suffused with light and color. He would go on to teach his students to see “the pomp of purple and gold,” the curator adds, “showing them techniques to paint sunlit landscapes and capture the richness of violet shadows.”

The Impressionists had embraced the use of cadmium pigments as they became available, for the vibrant yellows, oranges and reds did not degrade in sunlight. Whether conjuring the burning sun or glowing autumn leaves of a Monet painting or those by Paul Gauguin and Henri Matisse, the pigment made painting en plein air possible; it had become a serious part of the painter’s toolkit.

DuMond came up with the idea of a pre-mixed palette for students working outdoors, Pohrt explains, in which students could be presented with color scales that moved from light to dark and that functioned as color notes analogous to musical keys. The approach helped students identify value and saturation to understand how color is affected by light and shadow. And this aid could be transported in a paint box to save time and free the artist from having to adjust each color under shifting light and weather conditions.

“Yellow Roses” by Frank Vincent DuMond (American, 1865-1951), 1890. Oil on panel. Collection of Douglas & Marcia DuMond.

While nature can overwhelm the eye of the novice painter, DuMond’s palette could enable the aspiring student to move from “bewildering chaos” to see light.

Even so, Thomas Torak, a renowned realist painter who is on the current League faculty, remembers encountering the pre-mixed palette in his own student years, and finding himself “utterly baffled” by its purpose.

In what he cheerfully describes as his “blobscape period,” it was only when he realized that the palette was a template, “not scientific formula, but a means to get to something that looks like nature,” that he began to make progress. “And then it all flew.”

DuMond was offering a conceptual approach, and, indeed, his personal palette evolved as new pigments came on the market. According to John Varriano, a colleague of Torak’s and himself a renowned teacher and painter, DuMond was offering students an aid to master the rudiments, much as a piano student would be asked to study scales and master fingering.

Annual plein air teaching trips exposed both teacher and students to rich natural scenes in upstate New York, in Vermont and in the Margaree River Valley of Nova Scotia’s Cape Breton Island, and the exhibition showcases a number of memorable paintings from these trips. The exhibition includes as well a number of paintings by the artists who were influenced by him, including Charles Vezin (1858-1942), Ellen Axson Wilson (1860-1914), the wife of President Woodrow Wilson; John Marin (1870-1953), one of the first American artists to incorporate abstraction into his work; and Louis Bouché (1896-1969).

“Portrait of Elisabeth” by Frank Vincent DuMond, (American, 1865-1951), 1912. Oil on canvas. Florence Griswold Museum, gift of Elisabeth DuMond Perry.

Now more than 70 years after his death, his teachings continue to have an impact. Following his death in 1951, his advanced student Frank Mason was elected by League students to become their instructor. Mason taught at The League until 2009, and Studio 7, where he taught, remains in use by League instructors and students who study DuMond’s techniques to this day.

“I always feel that DuMond is one of the unsung heroes of arts education in the United States – his influence is so deep, and so profound – and his name is not known,” adds Varriano, who offers workshops on the pre-mixed palette in New York and New Jersey. His mission, Varriano adds, “was how to see and how to think; less in teaching you how to paint. His approach was more philosophical – in that he felt students needed to understand light conceptually. I’m grateful for that legacy.”

“There were no frills in his instruction, only real application and a love and respect for value,” Bouché wrote. “Frank DuMond loved to teach. He loved his students and in turn they adored him.”

The Lyman Allyn Art Museum is at 625 Williams Street. For information, www.lymanallyn.org or 860-443-2545.