“Portrait Vase” by Paul Gauguin, 1887–88. Unglazed stoneware decorated with slip, glaze and gold, 10¼ by 6-5/16 by 4-5/16 inches. Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen.

By James D. Balestrieri

ST LOUIS – French art historian Jean Leymarie, in his short, perfect essay on Paul Gauguin, published in the gorgeous dusty columns of the 1962 Encyclopedia of Art, sums up the birth of Modernism: “Painters no longer attempted to represent the external world by creating the illusion of an image, but rather to suggest their interior dreams through allusive symbols and the multiplication of decorative forms; line and color were invested with the role of expressive vehicles and became the abstract equivalents of sensation. This change, amounting to the overthrow of the empirical and optical vision that had come down from the Renaissance, was perhaps the most violent about-face in modern art. The way, from that time, was open, and we know how boldly Gauguin proceeded.”

Comprising 55 Gauguin masterworks on loan from Copenhagen’s Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, as well as some 35 objects from the collection of the Saint Louis Art Museum, “Paul Gauguin: The Art of Invention,” now on view in St Louis, offers a superb overview and deep insight into the life, thought and art of this quasi-mythological being whose shadow looms large not only over artistic Modernism but over the very romantic notion of the artist who sacrifices everything for art.

Along with many other artists in every discipline, Gauguin has been reappraised in recent years. His freedom and devotion to art above all came at a steep cost to others: the wife and children he left behind in Europe, the Native child brides he took in the South Seas and the children they bore him and hosts of friends – Van Gogh and Pissarro among them – who felt the sting of his wrathful restlessness. Along with this reconsideration of his approach to life, his art, which for a very long time has been seen as visionary and ahead of its time, has been studied in light of currents of thought in fin de siècle Europe – notably, the resurgence of mysticism, Kabbalistic practice and the Manichean duality of good and evil that finds its greatest expression in Nietzsche. Albert Boime’s book, Revelation of Modernism, is one recent example of attempts to locate Gauguin and his contemporaries as seekers of new ways of living life and making art in a culture whose ideas they saw as exhausted.

Gauguin’s own life, which has been the subject of a host of books and films, is still worth a skim. Born in France in 1848 into a family with socialist sympathies, Paul Gauguin emigrated with his parents to Peru when he was young, his mother having ancestral connections to a wealthy Peruvian family. His father died en route, and Gauguin, just a few years later, was sent back to France to be educated. He became a very successful stockbroker whose first interest in art was as a collector. He began to paint, and his work attracted the attention of artists he had met in the course of his collecting, especially Camille Pissarro. When the Paris Bourse crashed in 1882, Gauguin turned his full attention to art, even as his haute bourgeois life – and his family – fell apart.

After having settled his wife and children in Copenhagen, Gauguin determined that he would abandon middle-class morality – and his family – and go to Brittany, where he hoped to find inspiration, and a style of his own, in the traditional culture and wilder setting of the north of France. When that proved insufficient, Gauguin sailed first to Martinique and eventually to the South Seas, to Tahiti and the Marquesas, where he found a culture he saw as idyllic, prelapsarian, guided by desire and to natural law. After Martinique, he returned to France, where he painted and eventually came to blows with Van Gogh over the attentions of a prostitute – who would, the next day, be the recipient of the infamous ear, suspected of late to have been shot off by Gauguin in a duel rather than sliced off by Van Gogh himself (one of the rickety pistols claimed to have been used in that duel recently came to auction).

But perhaps Gauguin’s greatest influence came from Degas. The two were not only mutual in admiration, but also lifelong friends. And in looking at Gauguin’s work, the whole of his body of work, what you see of Degas in it – what I see, at any rate – is a restrained composure in both subject and treatment, a detachment and preoccupation that is never disdainful or even indifferent, as if the artworks themselves, not just their subjects, are lost – for the moment – in thought. They are everything that Gauguin seems not to have been in his life and mind: calm as opposed to turbulent.

Somehow, in between the jagged dramas of his life, Gauguin managed not only to make a great deal of art but to encapsulate a great deal of what was going on as the academic gave way to the modern. Gauguin’s early works hearken back to the Barbizon, of Corot’s spindly, mist-hung trees and solemn figures. Then, as he begins to paint with Pissarro, they take on classic impressionist trappings where small daubs of paint in layers build a picture. In Brittany, one begins to see the influence of stained glass and Japanese woodblocks – heavily outlined shapes, flattened picture plane, limited palette. Critics note similarities between his work and cloisonné enamel work as he absorbs the late Nineteenth Century revival of interest in Medieval arts and the Gothic. His work loosens and brightens then as impressionism gives way to post-impressionism and symbolism and he sees what Van Gogh and Cézanne are up to.

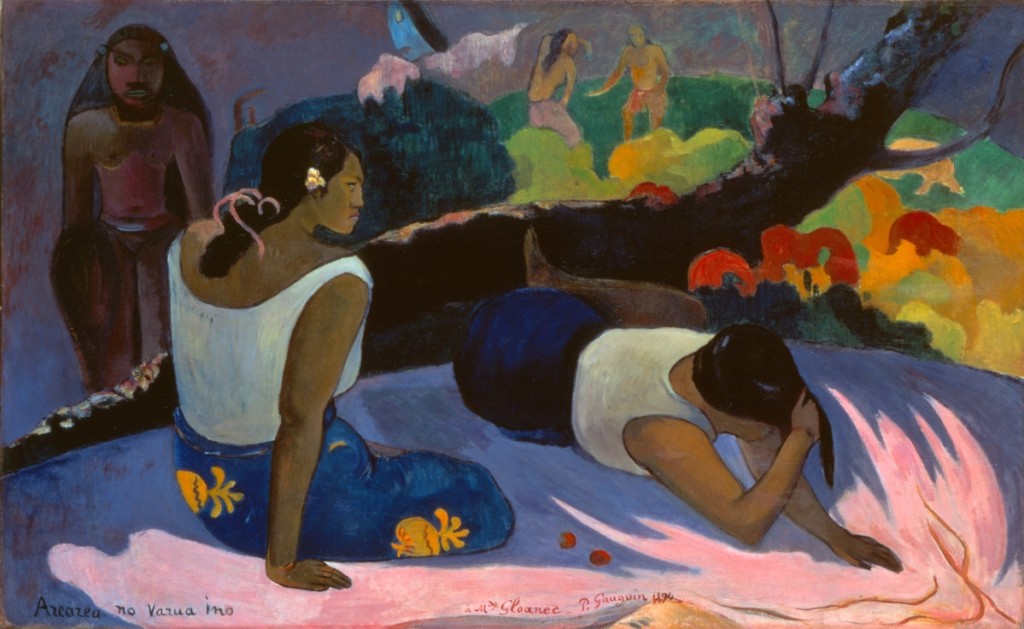

Then, at last, in Polynesia, Gauguin synthesizes all this and makes a leap to a personal style, becoming the Gauguin we recognize in major works such as the 1894 oil “Reclining Tahitian Women,” or “The Amusement of the Evil Spirit (Arearea no varua ino).” As a guess at a theme, jealousy and envy – perhaps represented by the dark figure at left and the blue face winging in on two clouds or over two peaks – seems to be tempting the frowning woman at left. Is she envious of the woman who reclines in front of her, absent-mindedly stroking her hair? Or is her frown directed at the men who seem to be dancing in the distance? Is she in love with the man who loves the woman she sits beside? Stories beg to be made up, but that’s all they are – made up – by us. Or does the fallen tree divide this world and another, a world one woman sees, while the other does not. These possibilities draw us in and keep us out. Despite Gauguin’s desire to express the new and to represent desire – the id, perhaps? – this painting and others he did in the South Seas seem to have roots in classical mythology, where capricious gods toy with human emotion to their own advantage and for their own amusement.

There are revelations in the exhibition, particularly in Gauguin’s ceramics and wood carvings. In an earlier essay for Antiques and The Arts Weekly (Issue March 2, 2018), I wrote about Picasso’s transformative moment in June 1907, when the artist wandered into the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro in Paris. But if you look at Gauguin’s stoneware works “Portrait Vase” and “Portrait Head,” you see an even earlier groping toward the forms of ancient and indigenous arts. Similarly, when you look at the open expression of the young woman and the flowing expressiveness that surrounds her in Gauguin’s woodcarving “The Singer,” you see an early incarnation of the unspoiled lightness that Matisse sought, in his dancers and elsewhere, throughout his career.

Catholicism and the Modern Mind (Esprit Moderne et Le Catholicsme), a diatribe against Christianity and Western Culture written and illustrated by Gauguin (and gifted to the Saint Louis Museum by actor Vincent Price) presents Gauguin’s strong feeling that dogma and institutional religion had stripped mystery, myth and true spirituality from the human mind and heart and that these could only be rediscovered in cultures that had not yet been tainted by the Church. Gauguin’s woodcuts and transfer drawings on the book’s covers and inside pages mix Polynesian and Western tropes, and you can see how the artist rubbed and wore away at the images to make them seem like something out of a lost manuscript.

“Reclining Tahitian Women” or “The Amusement of the Evil Spirit (Arearea no varua ino)” by Paul Gauguin, 1894. Oil on canvas, 23-5/8 by 38-9/16 inches. Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen.

The truth is, Gauguin would scorn our moral condemnation. He would relish being the poster boy for the difficulties we face as we attempt to reconcile (or separate) the failings of the artist as a human being with the beauty and influence of the artist’s work. If we dismissed him and his work, he would probably laugh. As Leymarie writes at the conclusion of his essay: “Gauguin was largely responsible for all of the modern esthetic, with its direction rather toward suggestion than description – anti-naturalism, simplification and poetic and rhythmic effect in painting; purity of line; creative autonomy of color; the break with the Greco-Latin and Renaissance tradition; the appeal to the imagination, to dreams, to the unconscious and to Oriental and primitive sources. His immense influence on practice and theory was greater than his own creations.”

Gauguin’s own words, as Leymarie quotes them, confirm this and attest to the artist’s extraordinary knowledge of himself, his failings, his limitations and his fierce defense of his libertine choices: “‘I wanted to establish the right to dare everything; my capacities (and the financial difficulties of my life have been too much for such a task) were not capable of great results, but the machine is none the less launched. The public owes me nothing, since my pictorial oeuvre is but relatively good, but the painters who today profit from this liberty owe me something.'”

Today, as a recent piece in The New York Times asserts, the artist as transgressive, as wild, instinctive, awful and awe-inspiring has been displaced in large measure by the artist as ascetic, as a solitary, nose-to-the grindstone, driven, sometimes haunted figure. You find versions of asceticism in three of the dominant strands of art: the politically charged; the revivals and revisions of isms-real, surreal, and everything in between; and even among those who see art primarily as fun. There have been ascetic periods in the past; there will be transgressive periods in the future. The pendulum of morality swings between them. Art has a way of anticipating these swings. In the end, while you might find a certain kind of dark asceticism in Gauguin’s work, you would never find Gauguin the man among the ascetics.

Tickets are $15 for adults, $12 for seniors and students, $6 for children 6-12, free for children 5 and under, and members are always free. Exhibition hours are Tuesday-Sunday, 10 am to 5 pm; Friday, 10 am to 9 pm; closed Monday. The Saint Louis Art Museum is at 1 Fine Arts Drive, Forest Park. For more information, www.slam.org.