Standard carried during pilgrimage to the shrine of the Prophet Ezekiel in Al-Kifl, Iraq, 1826-27, silver, 9-7/8 by 4½ by 3/4 inches. The Jewish Museum, New York. Purchase: Judaica Acquisition Fund, 2000. Formerly in the David Solomon Sassoon Collection.

By Laura Layfer

NEW YORK CITY – Family trees can offer fascinating stories of lineages that have merged and diverged by way of relationships and regions. “The Sassoons,” now on view at the Jewish Museum in New York, traces four generations of the family of David Sassoon (1792-1864), through an examination of their collective and diverse connoisseurship practices. Often labeled the “Rothschilds of the East,” the wealth of the Sassoons is recognized most notably for their patronage of fine and decorative art, artifacts and architecture. Visitors to the exhibition are led through the family’s travels from Iraq and India to China and England. Beginning in Baghdad with patriarch David, who built a vast trade empire, ultimately it is a myriad of Sassoon matriarchs that emerge as largely responsible for ensuring this artistic legacy.

Organized by Claudia Nahson, Morris and Eva Feld senior curator at the Jewish Museum, and Esther da Costa Meyer, professor emerita at Princeton University, the show will be on view through August 13, 2023, with more than 120 works from private and public collections and an accompanying catalog of essays and illustrations. “The scope is broad chronologically and historically from the 1830s to the end of World War II,” says Nahson, “the palette is so rich because of the amount collected by many different family members, and the way these treasures visually share their journey.” Together, Nahson and da Costa Meyer have explored individual Sassoon family members, their personal plights and complicated devotion to religion and culture. Alongside paintings by John Singer Sargent and Thomas Gainsborough are Chinese scrolls and ivory carvings, important Judaica, and Hebrew manuscripts, the earliest dating back to the Twelfth Century.

The opening gallery features a portrait, probably from the mid-Nineteenth Century, and attributed to William Melville, of David. “He sets the narrative into motion,” notes Nahson. David is shown in garb reminiscent of his Baghdad roots with scenery of Mumbai (formerly Bombay) in the background; a presentation that depicts the contrast of old and new ties. “In the early 1830s, the Pasha target some Jewish families for expulsion, including the Sassoons,” says da Costa Meyer, “even though others were able to stay up until the Twentieth Century.” When David emigrates to Bombay, he first makes a modest living as a merchant dealing with spices, cloth and goods, but later, as more ports open, his success is solidified with the most lucrative commodity of the moment, opium.

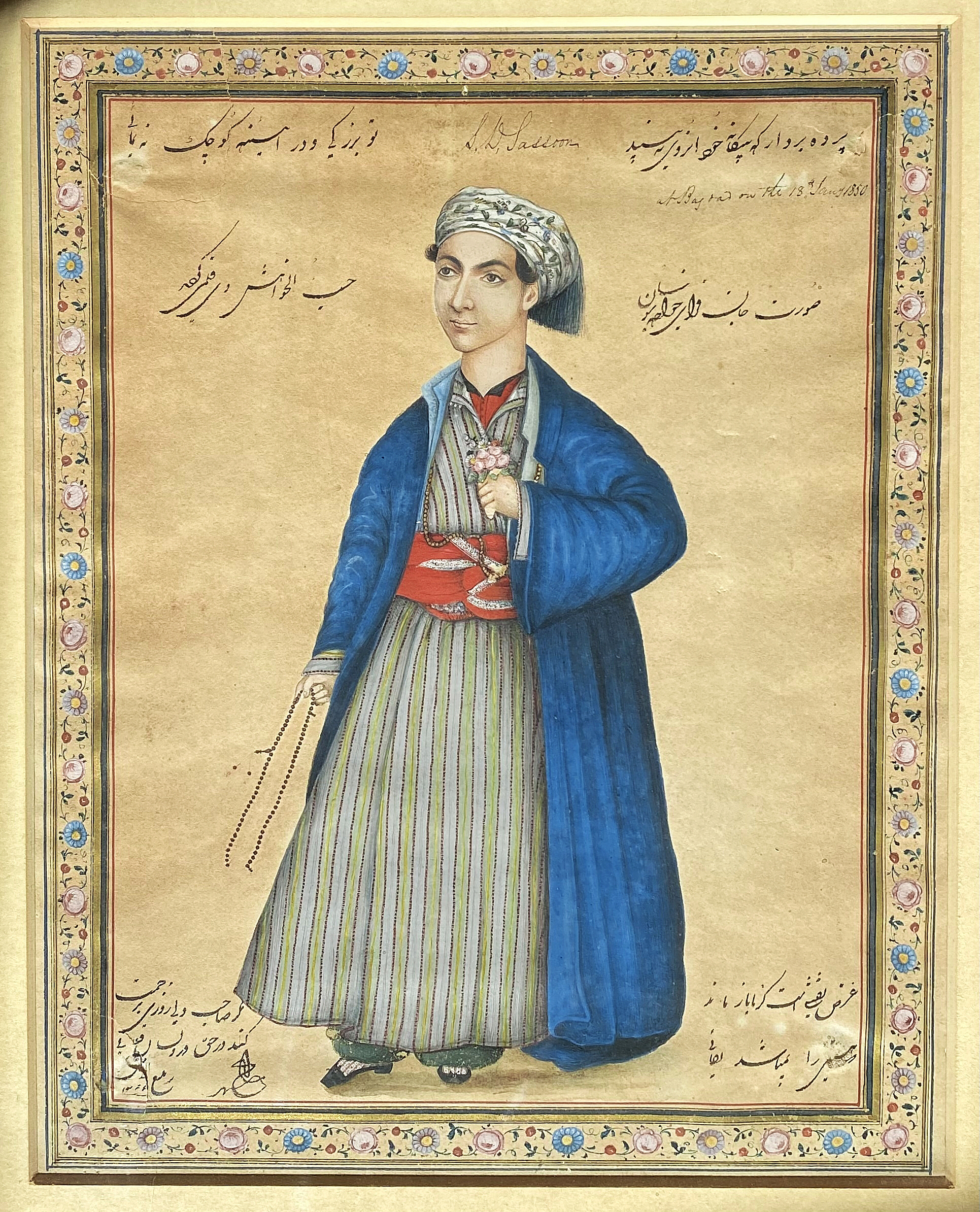

David married twice, the initial courtship produced two sons, and six more male heirs from a second marriage, so the firm, David Sassoon & Co, never found itself at a loss for leadership. David’s sons were the chosen representatives designated to expand their father’s company. As adults, the men were deployed far and wide from Shanghai and Hong Kong to London. A photograph captures David with some of his sons, with one, Sassoon David Sassoon (1832-1867), adorned in Western attire, a preparatory look for an anticipated departure abroad. By contrast, the other siblings are donned in customary Indian style clothing. “David, interestingly, always wore Baghdadi Jewish clothing in India, where he also stood out,” remarks da Costa Meyer.

“Sybil, Countess of Rocksavage” by John Singer Sargent, 1922, oil on canvas, 63½ by 35-5/8 inches. Courtesy Houghton Hall Collection, used by permission Painters / Alamy Stock Photo.

The Sassoons supported the building of synagogues, schools and hospitals in India, Asia and Europe. Their efforts to create and cultivate Jewish life were personal and professional as David was very involved in assisting other Jewish families with immigrating to India, employing many of them. The Sassoons invested in their new homelands, and when they started to take residence in England, they navigate in a high society circle, including even the monarchy. Sir Phillip Sassoon, a grandson of David, becomes a member of Parliament for the Conservative Party, and a prolific collector of Eighteenth Century art that fills his three homes between London and Kent. Phillip’s cousin, Hannah, is known to have frequently gone antiquing with Queen Mary. The roster of lenders to the exhibition includes His Majesty King Charles III.

Flora Sassoon (1859-1936), the widow of one of David’s sons, Solomon Sassoon, took over the Bombay offices after her husband’s passing, and eventually moves with their three children to England. She is part of the provenance of much of the important Judaica highlighted in the galleries, including Torah and haftarah scrolls in cases of silver-gilt and enamel, commissioned in Iraq and China in the late Nineteenth Century. Such scholarly pursuits were unusual for women to display during that period. Flora, however, is not only able to cultivate a full life in London for herself but does so while still adhering to Jewish dietary laws, daily prayer and is purported to have read before a Baghdad congregation from a Torah once donated by her father-in-law.

“There is this bond between the Jewish impact and the commercial impact, and the way each family member finds a way to remain linked to their original community, in Baghdad, in religion, while still separating and establishing stature financially, socially and politically,” says Nahson. She describes one of the highlights to be the gallery displaying a trio of Sargent portraits. There are two of “Sybil, Countess of Rocksavage,” from 1913 and 1922 (a great-granddaughter of David), and a third of her mother, “Lady Sassoon,” 1907 (born Aline de Rothschild who married into the Sassoon family, inextricably linking the two well-known names). Sargent was a close friend of the family, and Sybil became a favorite and fashionable subject of the artist. In the latter of the two paintings, she is wearing a dress commissioned from the House of Worth by Sargent for her. The works are on loan from Houghton Hall, designed by William Kent in the 1720s, and originally built for Robert Walpole, the first Prime Minister of Great Britain. In 1919, Sybil and her husband, George, Earl of Rocksavage, take residence at the Palladian style country house. Sybil was instrumental in the restoration of Houghton Hall and preserving its original interiors and holdings.

Sassoon Haggadah, Spain or southern France, circa 1320, ink, tempera, and gold and silver leaf on parchment, 8-5/16 by 6½ inches. Purchased by the State of Israel through an anonymous donor, London. Formerly in the David Solomon Sassoon Collection.

Rachel, a granddaughter of David, is a family member that both Nahson and da Costa Meyer felt “big heart” for during their research. “She was such a modern-day woman,” comments Nahson. Rachel played music, enjoyed meeting artists (her extensive fine art collection would be sold at auction in 1927), and did not tie herself to marriage until finding the perfect match in education and intelligence. Frederick Beer was the owner of The Observer (the publication had been passed down from his father), and a descendent from the Frankfurt Court Jews of the Eighteenth Century. He was baptized as a child, and Rachel also converted, leading to a cold reception by most of the Sassoon family. In the pendant portraits the couple had done by artist Henry Jones Thaddeus, Rachel appears feminine, sophisticated and to a certain extent, the independent person the course of her path dictates. She becomes a journalist, and the first female in Britain to edit two publications as she goes on to additionally acquire The Sunday Times. She reports on the Dreyfus affair in 1898, with a revelatory interview that offers previously unknown incriminating information to aid in the case of the Jewish French officer, Captain Alfred Dreyfus. He was re-tried after Rachel’s article and was again found guilty, and later exonerated in 1906.

During World War II, the Sassoon’s were actively involved in helping Jews leave Europe. China and India did not close their doors or enforce quotas, as other countries had, and with the Sassoon’s ties in those locales they were able to use many of their real estate properties to shelter refugees. Today, most of what remains in situ for the Sassoons are those same brick-and-mortar structures that came to the rescue of others in the last century. This May, Sotheby’s will auction the Codex Sassoon, dating to the late Ninth or early Tenth Century; it is the earliest copy of the Hebrew bible and referred to by its name after one of its most memorable owners, David Solomon Sassoon (1882-1942), a major collector of manuscripts, and the son of Flora. It is a prime example of the depths and extent of collections amassed, and a reminder of the rare opportunity now available to attend a family reunion seen through works of art that, with their provenance, will always endure.

The Jewish Museum is at 1109 Fifth Avenue at East 92nd Street. For information, 212-423-3200 or www.thejewishmuseum.org.