“Girl with a Cape” by William Edmondson (American, 1874-1951), no date. Limestone, 26½ inches high. Cheekwood, Nashville. Gift from the Estate of Elizabeth Lyle Starr.

By Karla Klein Albertson

NASHVILLE, TENN. – William Edmondson (1874-1951) was born in Davidson County, Tenn., and it was there in Nashville that – after many years of ordinary hard work – he found his calling as a stone carver. Without formal training as a sculptor, he developed a distinctive style that mixes strength and poignancy. While he made many utilitarian pieces, these qualities particularly shine through in his distinctive human figures.

Recognition of his achievements and range has expanded dramatically in the Twenty-First Century, matched by a strong upswing in prices for carvings coming to the art market. While everyone may think they already know this artist’s story, Cheekwood Estate has put together “The Sculpture of William Edmondson,” to take a fresh look at his life and body of work, most fittingly in the town where he plied his trade as a maker of tombstones, garden ornaments and stonework.

The institution’s curator-at-large Dr Marin R. Sullivan put together the exhibition and accompanying catalog of scholarly essays and illustrations. As the first large-scale museum exhibition of his work in more than 20 years, the show includes 41 sculptures, of which 19 are from Cheekwood’s own permanent collection and 22 on loan from private and public collections across the United States. There are also more than 20 archival photographs of Edmondson and his sculptures taken during his lifetime. The physical installation will be divided between Cheekwood and galleries at Fisk University, a private historically Black university in Nashville, and runs through October 31.

Installation image, “The Sculpture of William Edmondson: Tombstones, Garden Ornaments, and Stonework” at Cheekwood. Photo Cheekwood.

Talking with Antiques and The Arts Weekly, Sullivan spoke of how the exhibition came together: “My training is very much Twentieth and Twenty-First Century sculpture, and I’ve focused on that in my career. When I took the position here, I knew that they had this tremendous resource of William Edmondson works, so it was a nice fit. We started talking about the show as one of my primary tasks when I first became associated with the institution. I’ve spent two years working on it. The show’s changed a number of times just because of the pandemic, which has affected loans and the status of other institutions.”

In the end, the curator has been thrilled by how the exhibition worked out: “For me, the emphasis behind the show is really about Edmondson, about recentering him in his own art historical narrative. And I’m proud that it’s an opportunity to highlight and focus on Cheekwood’s collection of Edmondson and Edmondson-related works. We are stewards of a really incredible collection and being able to make that more accessible and widely available to the public has been at the heart of this show. We have been fortunate to get the top American exhibition grants from the Terra Foundation, the Luce Foundation and the Wyeth Foundation. This places an emphasis on collections in institutions – if you really want to know more about Edmondson, come to Cheekwood, which is a leading resource for his work.”

Collectors interested in this field will remember “The Art of William Edmondson,” a cataloged Cheekwood exhibition in 2000 that traveled nationally. Why do another 20 years later? Sullivan responded, “First and foremost, to introduce new audiences since he has become so deeply ingrained in the history of art. Some people aren’t as aware as they could be of why he was such an important carver and artist, so introducing new audiences is such a huge thing. For people who are more familiar, both regionally and nationally, we can try to recenter Edmondson in his own narrative. Like so many other self-taught artists, there are myths around their discovery and their place in the art world and the market that become so entrenched. This is a fresh examination of Edmondson and his role in art history. The essays we got from our contributing authors shed a completely new light on how we can approach this artist.”

“Bess and Joe” by William Edmondson (American, 1874-1951), circa 1930-40. Limestone, 17¼ inches high. Cheekwood, Nashville. Gift of Salvatore J. Formosa Sr; Mrs Pete Formosa Sr; Angelo M. Formosa Jr; and Mrs Rose M. Formosa Bromley in memory of Angelo Formosa Sr, wife Mrs Katherine St Charles Formosa; and Pete A. Formosa Sr and Museum Purchase through the bequest of Anita Bevill McMichael Stallworth.

The emphasis on “recenter” reminds readers of Edmondson’s well-known “origin story.” He was a deeply religious man, who felt he was called by God to pick up his tools and begin carving. Quite naturally, tombstones for the fallen were among his first works and topped the sign over his workshop. He continued carving pieces of discarded limestone, drawing inspiration from people he knew and creatures that he saw. The emphasis is always on his “discovery” by art enthusiast Sidney Hirsch, who spread the word to wealthy collectors, and in 1937 Edmondson was the first African American artist to be given a solo show at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. But this did not lead to lasting commercial fame and fortune for the sculptor, who died a quiet, pious man in Nashville.

Sullivan noted, “He was a funny, kind, engaging human being, but he always took his work very seriously. He set out to be a professional carver while it was also a calling that had a connection to his spirituality. What impresses me, he came to carving very late in his life, already in his 50s after he’d worked at a series of jobs. In the beginning of the Great Depression in Nashville, he decided, ‘I’m going to start carving, I’m going to make this my professional business.’ The title of the exhibition comes from the sign that was in the yard of his studio. He made things for people to use, to have in their everyday lives, and he drew from everyday life. I tried to understand how he thought of his practice: What was he making these sculptures for? And it was very much a creative, aesthetic pursuit.”

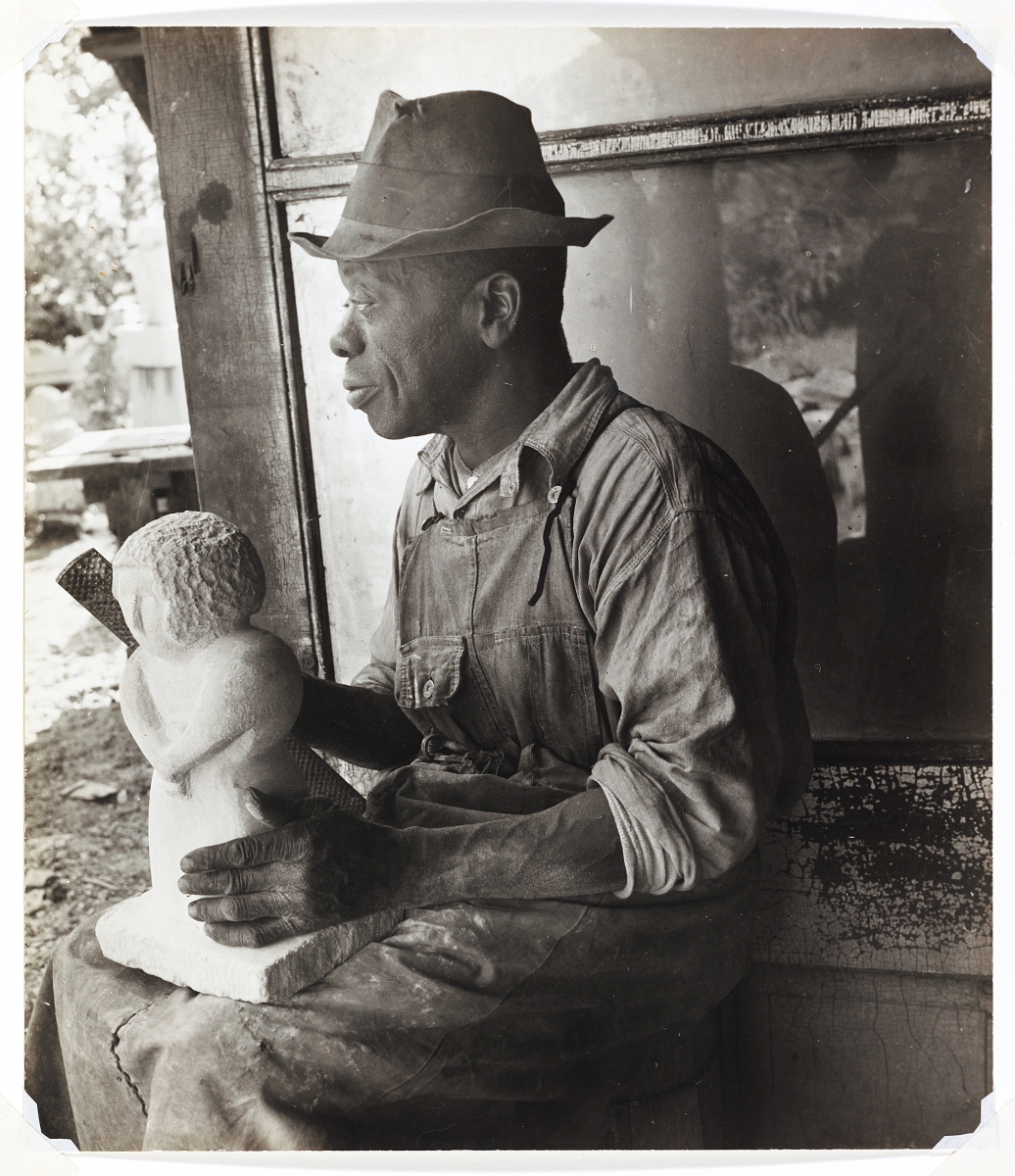

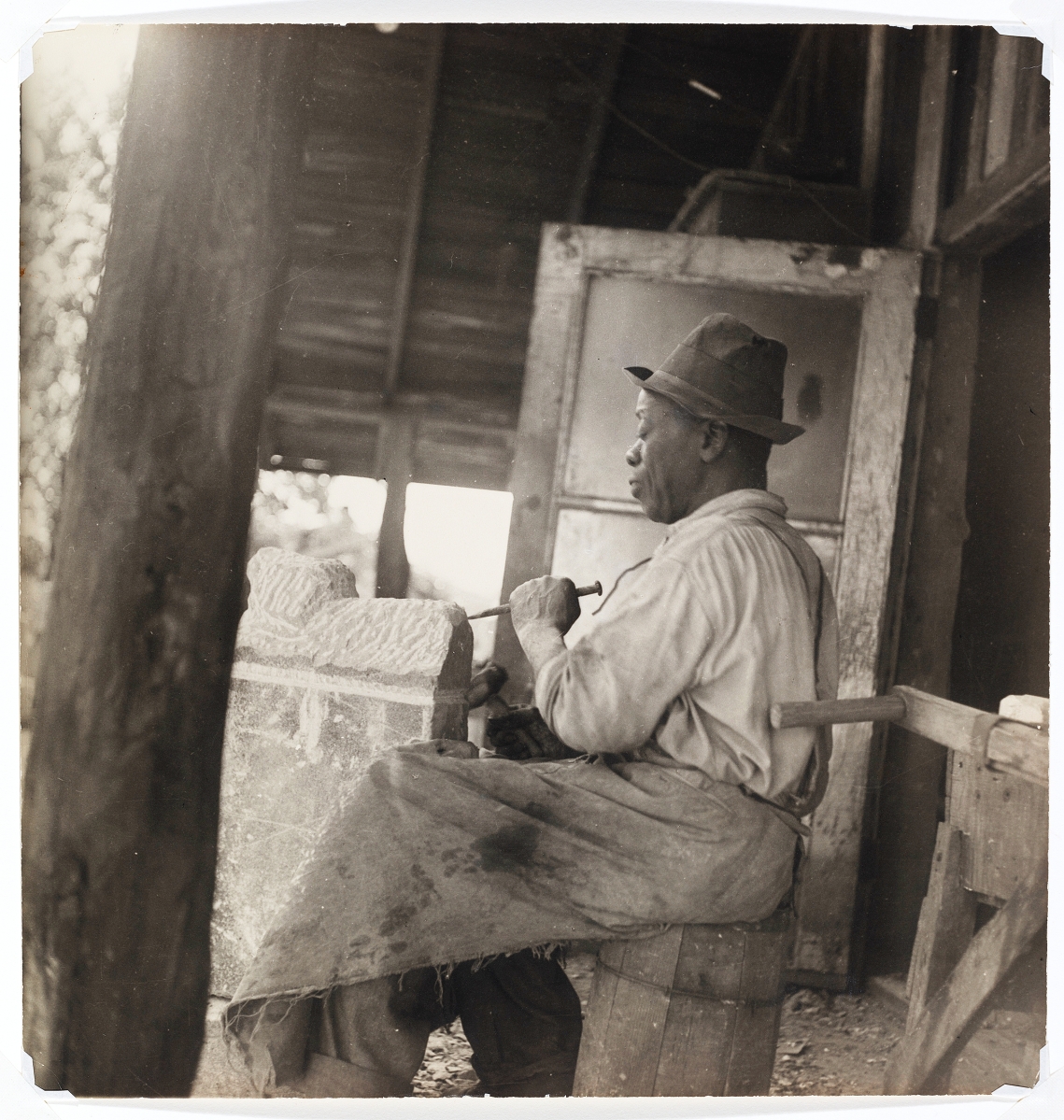

One blessing of Edmondson’s discovery in the 1930s was that it drew superb photographers who captured the carver in the shade and sunlight of his Nashville workshop. In some, he sits by or works on recognizable examples, and this humanizes the impressions created by the silent stones on a plinth standing side by side. Cheekwood has a large collection of gelatin silver prints by Louise Dahl-Wolfe (1895-1989), who was well-known as a fashion photographer at Harper’s Bazaar. The curator adds, “These are the images that become the de facto images of the carver. When we think of Edmondson, it’s through her lens. That’s a lovely historical record and document but as we know, all photographs are constructions, an encounter between photographer and sitter.”

Portrait of William Edmondson by Louise Dahl-Wolfe, 1937. ©2021 Center for Creative Photography, Arizona Board of Regents / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

This modest workman, who found both inspiration and enjoyment in his work, would be surprised by the astonishing prices recently realized for his efforts. Just as many of Edmondson’s works remain in Tennessee collections, others have brought stellar prices in the state at the Knoxville auction house of John Case. The firm was the sponsor of the exhibition opening night party at Cheekwood.

In recent sales, figural carvings have ruled with “Miss Amy” bringing $240,000 and “Miss Lucy” $324,000 in 2019, and “The Preacher” $540,000 in 2020. Even a chunky animal “Critter” brought $120,000 in the recent July sale. Case admitted, “As far as what we’re seeing in price points, that’s been quite surprising. I know the African American market is obviously strong, it’s a little bit challenging to come up with estimates. If you notice, we kept the estimate fairly conservative on the Critter. What we were really excited about is that the winning bidder is a Tennessean.”

“As you read about the man, what shines through is his personal integrity and the inspiration that started him down the path of carving these figures – being given a vision at a later age. And what a large body of work he was able to produce during his lifetime. What’s amazing is, he was a person and if you kept scratching, he was the same through and through. Even with the MoMA exhibit and later in life, there was a sense of humility with him about the vision that never appeared to be corrupted. He’s really been one of my heroes among Tennessee artists. So I have to believe that also has that larger appeal in the market right now.”

Installation image, “The Sculpture of William Edmondson: Tombstones, Garden Ornaments, and Stonework” at Cheekwood. Photo Cheekwood.

“I am a bit taken aback by how quickly his work has climbed in terms of what it’s bringing in the art market,” Case continued. “Now, when his work comes up, there are bidders with art investment firms in the hunt. While that shows his legitimacy in the world art market, it is a bit sad that we are going to see these sculptures not only leaving Tennessee but also the United States as he becomes more renowned. We’re fortunate to have many of his works still here in the state. The exhibition is a great opportunity to examine his work on a scale not possible before. It’s going to be difficult to assemble this number of objects ever again.”

With this upswing in prices, not surprisingly Edmondson sculpture has been back on display in New York, both on view in museum collections and on the auction block. Cara Zimmerman at Christie’s said, “We have seen tremendous development in Edmondson’s market over the past decade, and Christie’s has had the honor of handling remarkable works by the artist during this time. We hold the world auction record for a piece by William Edmondson with “Boxer,” which we sold in 2016 for $785,000. His figurative works have historically been the most sought-after part of his practice, though in the past five years we’ve seen a substantial rise in value across his oeuvre, ranging from vessels – a simple two-handled cup sold in 2020 for $175,000 – to animals like the lion which brought $511,500 in 2017.”

William Edmondson was an inspired carver and a humble man who has gone beyond earthly admiration. For those who remain behind, there is the illuminating exhibition at Cheekwood and comprehensive catalog published by the Vanderbilt University Press.

Cheekwood Estate & Gardens is at 1200 Forrest Park Drive. For more information, www.cheekwood.org or 615-356-8000.