“Emigrants Crossing the Plains” by Albert Bierstadt (1830–1902), 1867. Oil on canvas, 60 by 96 inches. National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum

By James D. Balestrieri

DENVER – The vital founding myth of the American West might be defined as the set of stories – historical truths mixed with fables, legends, larger-than-life characters, archetypes and stereotypes – that create solitary, rugged individualists making their way in a wide, wildly beautiful and supremely forbidding environment. “The Western: An Epic In Art and Film,” arranged by the Denver Art Museum and the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, and on view in Denver through September 10, charts the vibrations between exploitation and expiation, between nation building and its devastating costs.

In 1893, University of Wisconsin professor and historian Frederick Jackson Turner (1861-1932) first publicized his theory that the frontier, as an idea, was what shaped American democracy and that, in effect, the frontier was closed. The openness to possibility and the “pursuit of happiness” embedded in the frontier had given way to the civilizing forces of Westward expansion. Though this theory has been challenged many times and on numerous grounds, it had an immediate, game-changing effect and gave rise to the mythical West.

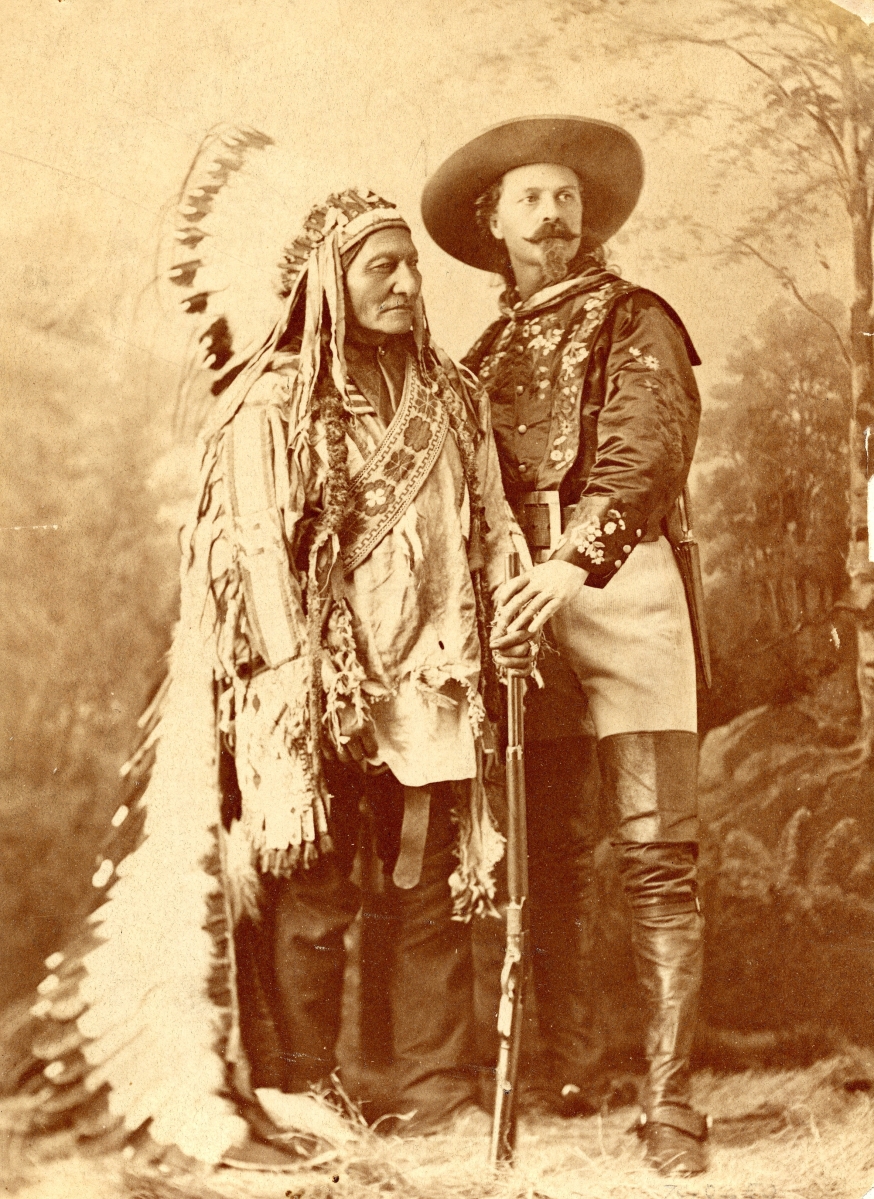

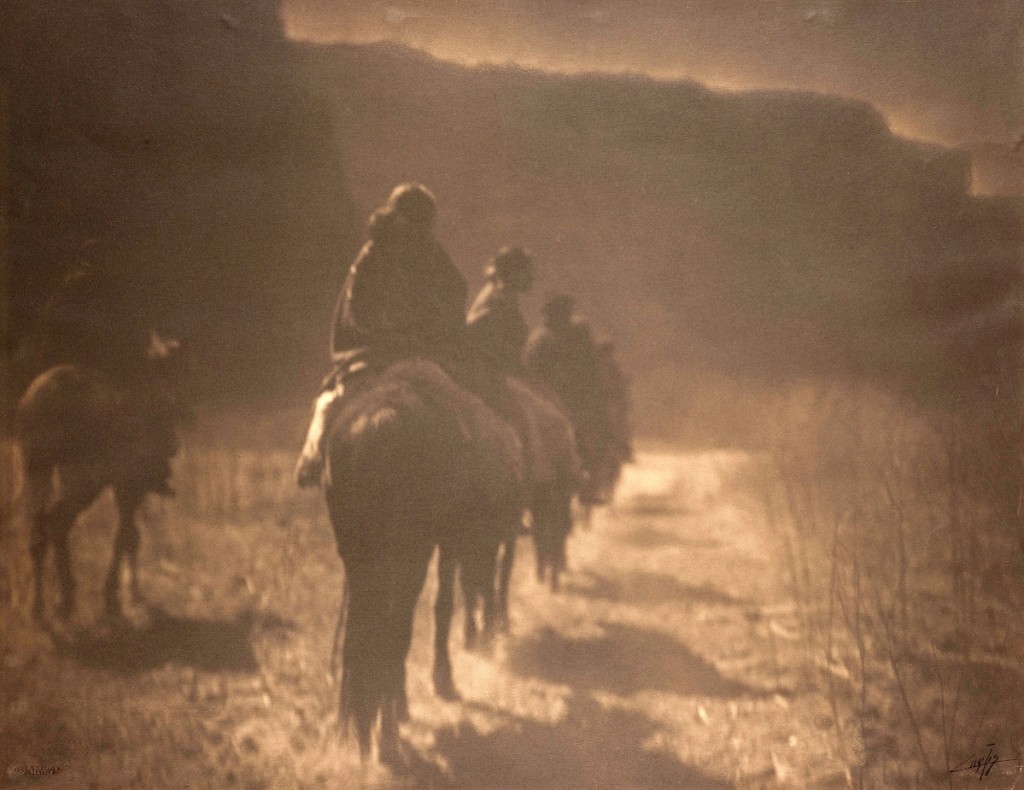

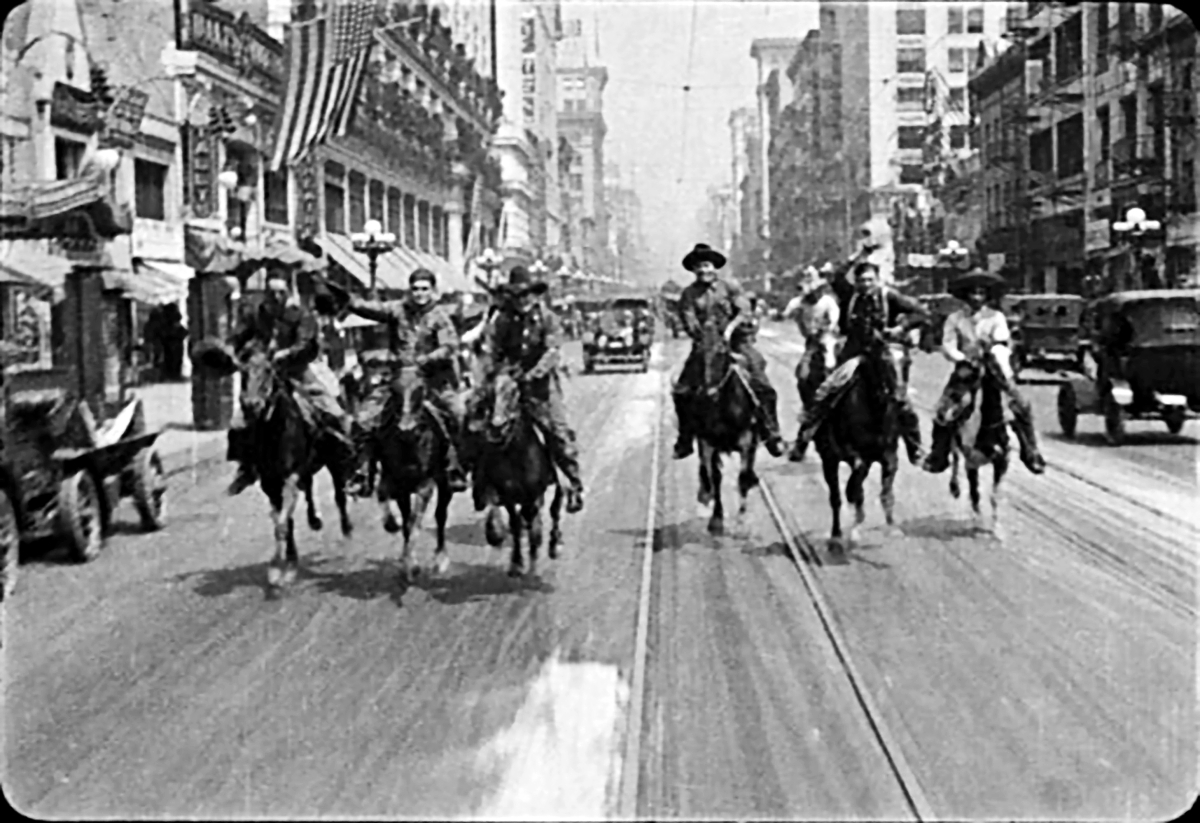

In that same year, 1893, Thomas Edison (1847-1931) made the first Kinetoscopes, leading to the motion picture. By 1895, Frederic Remington (1861-1909) was turning his art from painting to bronze, sculpting “The Broncho Buster,” as it was then titled, while author Owen Wister (1860-1938), a friend of the artist, was transforming the cowboy from a Wild West vagabond into a knight errant of the range in novels such as The Virginian. The race was on to capture the vanishing West, and the vanishing Indian. Consider Edward S. Curtis’s (1868-1952) lifelong project to photograph Native Americans as they were, even if it meant asking them to take the clocks off the walls of their hogans, and to make the violent history of Westward expansion into a morality tale that would serve the nation.

But even those who were most closely involved with the making of the mythical West sometimes faced uncomfortable truths. One of my favorite Remington quotes is in his response to Wister’s new fictional cowboy as a courtly – and very white – knight: “Strikes me there is a good deal of English in the thing – I never saw an English cowboy – have seen owners. You want to credit the Mexican with inventing the whole business – he was the majority of the ‘boys’ who first ran the steers to Abilene, Kansas….” But the vaquero was largely scrubbed from canvas (Edward Borein’s paintings were notable exceptions) and from film until Zorro and the Cisco Kid.

But even those who were most closely involved with the making of the mythical West sometimes faced uncomfortable truths. One of my favorite Remington quotes is in his response to Wister’s new fictional cowboy as a courtly – and very white – knight: “Strikes me there is a good deal of English in the thing – I never saw an English cowboy – have seen owners. You want to credit the Mexican with inventing the whole business – he was the majority of the ‘boys’ who first ran the steers to Abilene, Kansas….” But the vaquero was largely scrubbed from canvas (Edward Borein’s paintings were notable exceptions) and from film until Zorro and the Cisco Kid.

A scant 15 years later, in 1908, painter Herman Hansen (1854-1924) wrote, validating Turner’s thesis, “Tucson is killed from my point of view. They have shut down all the gambling houses tight, and not a gun in sight. Why, the place hasn’t the pictorial value of a copper cent any longer.”

The light in Hollywood and the landscape of Southern California made Westerns a perfect subject for motion pictures. Their picturesque appeal and simple morality – black hats versus white hats, savages versus noblemen – suited the pictorial nature of silent film. As sound and color were added to film, the West and the Western flourished. Only after World War II did a kind of anti-colonial moral complexity and ambiguity enter the Western.

Justus D. Barnes in The Great Train Robbery, directed by Edwin S. Porter (uncredited), Edison Manufacturing Company, 1903.

The show’s curators focus on film and on thematic connections between film and Modernist treatments of Western subject matter and practice. Jackson Pollock (1912-1956), who was born in Wyoming and whose ties to the American West are well documented, is here aligned with the great Western films, not in any narrative sense, but in the act of creating his horizontal action paintings. Pollock merges with his art, even as Alan Ladd does at the end of George Stevens’s Shane, disappearing into the vast Western horizon. Andy Warhol’s West is a place of repressed homoeroticism and colonial violence.

In works such as “It Was Never About Playing Cowboys And Indians,” contemporary Native American artist Gail Tremblay weaves film into Mi’kmaq baskets, appropriating and subverting the medium that engendered and perpetuated so many stereotypes. Kent Monkman (b 1965), another Native artist, revisits classic Western artworks, infusing them with historic violence and repressed sexuality, removing any trace of “nobility” from the “savagery” of North American empire building and resistance to conquest.

Some omissions are glaring. Where are the postwar illustrators of the innumerable Western pulps, men’s magazines, Louis L’Amour paperbacks and comic books? Where are the Cowboy Artists of America, who emerged in the 1960s? Where are the contemporary painters and sculptors of the American West, artists such as Howard Terpning, Kyle Polzin, John Coleman and others? What about radio and television productions such as Gunsmoke, Bonanza and Have Gun Will Travel? What about the Marlboro Man? These popular artists and the works they created are well known and widely prized.

“Breaking Through the Line” by Charles Schreyvogel (1861–1912), no date. Oil on canvas, 46¼ by 58-3/8 inches. Gilcrease Museum

Stories serialized and illustrated in magazines like the Saturday Evening Post furnished material for John Ford, Howard Hawks and many other makers of silver-screen Westerns. Ford made John Wayne look like something out of Remington, Russell and Schreyvogel, but Ford also owed a debt to – and owned – works by Harold Von Schmidt and other illustrators. In fact, Ford owned a painting Von Schmidt did as a poster for The Searchers. Whose work did the Duke own? Olaf Wieghorst, Russ Vickers and other Western narrative realists. Wieghorst’s paintings appear in the credits of El Dorado and McLintock!, while Vickers’s works appear under the credits in Chisum. Frank McCarthy and Carl Hantman painted posters for 1960s revisionist Westerns such as Duel at Diablo and Hondo. Surely the line between the forced perspective of Ed Ruscha’s gas stations vanishing into the Western horizon and the hard-edged, folded forms of Ed Mell’s desert peaks, clouds and storms merits further investigation.

In Western art, the defeat and decimation of Native people and the herds of great game animals is a loss. They are noble, but doomed. This is, in fact, a good definition of tragedy. But that sense intensifies immensely when the cowboy vanished in the tentacles of the railroad. The myth of the American West articulates a yearning, a nostalgia for the danger in the often lethal struggle for ownership and mastery of the West, and for the very real uncertainty of the outcome. United in defeat, the cowboy, the Indian, the buffalo, the wolf and those who devoted their art to them all share something that no one after them will ever know. Russell, Remington and the rest got this.

No single exhibition can or should be exhaustive. “The Western” does a great service by broadening the mythology of the American West to embrace Canadian art and history, and to connect Western tropes to the broader currents of Twentieth Century art. But I am reminded of Jimmy Stewart’s line – which appears early in the exhibition catalog – in John Ford’s masterpiece, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valence: “This is the West, sir. When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.”

“The Vanishing Race — Navaho” by Edward S. Curtis (1868–1952), 1904. Platinum print, 16 by 20¾ inches. Denver Art Museum

Once upon a time, I was walking with my wife in Brooklyn and an African American in full cowboy regalia, down to woolly chaps and 10-gallon hat, came riding a palomino down Court Street. He stopped at a bar, threw his mount’s rein around a lamppost and went in. He was part of the oldest rodeo in America, a rodeo for black cowboys.

Once upon a time, I was in a casino in Reno, attending the Coeur d’Alene art auction. The casino, under construction, had stumbled on the remains of an enormous saloon and dance hall, owned by African Americans. Empty bottles of wine, imported from France, littered the site.

One upon a time, my Uncle Tom, born in Sicily in 1899, went to Wyoming to be a cowboy.

My current favorite works of Western art are a painting by Richard Lorenz (1858-1915), circa 1890, of a woman in a pink bonnet and a Hispanic man herding cattle, and a small drawing of 1885 by Rudolf Cronau (1855-1939) titled “Broadway of A Western Town.” In the drawing, a Star of David is printed on a crate. “Jacobs’ Oil” can be seen painted on the side of a building, while an African American boy on the wooden sidewalk sells goods, a mother holds her son’s hand and an Indian listens to two buckskin-clad men debate in the street. Loaded wagons make for the distant mountains and what might be the Anheuser-Busch eagle sits atop the “Mammoth Sleeping Palace.”

Once upon a time, Charlie Russell sailed to London, where an exhibition of his paintings was to be held. It was not a success. One day Charlie met an Italian Futurist, whose London exhibition had also been a flop. In one of his famous illustrated letters, Charlie records this meeting, says he did not understand anything the Italian said – language barrier notwithstanding – but, on this same letter, Charles M. Russell, of Great Falls, Montana, paints a darn good little piece of Italian Futurism. Like the cowboy and the Indian, the Western painter and the Italian Futurist overcome their differences and bond – and are bound – through art, having been defeated by the forces of civilized conformity. Makes me wonder whether, despite Turner’s Frontier thesis, the West and the Western, as a myth to be mined by art, are still untamed, and largely unexplored.

Following its close in Denver, “The Western” will be on view in Montreal from October 14 to January 28. The Denver Art Museum is at 100 West 14th Avenue Parkway. For more information, www.denverartmuseum.org or 720-865-5000.

Jim Balestrieri is director of J.N. Bartfield Galleries in New York City.

.jpg)