The 1948 charcoal and pencil on paper drawing “Christmas Homecoming, 1948” by Norman Rockwell was $1.1 million at Jonathan Boos, New York City. It is preliminary to a painting of the same name, now at the Norman Rockwell Museum and published on the cover of The Saturday Evening Post on December 25, 1948. All five members of Rockwell’s immediate family are depicted.

Review by Laura Beach, Photos Courtesy The Winter Show

NEW YORK CITY AND ONLINE – However commonplace it has become to describe the last ten months as a time of paradigm shift, it is hard to overstate the transformation undergone by this year’s Winter Show, a New York tradition since 1954. This was only the third time the fair – which concluded on January 31 after a 13-day run, including a three-day VIP preview – was dislodged from its traditional home, the Park Avenue Armory. The last time, in 2001, followed the attacks on the World Trade Towers.

Gone this year was the sumptuous loan show, the advertising-laden print catalog, the logistics of move-in and pack-out, the camaraderie of building the show and vetting it by teams of experts working in close physical proximity. Gone were the preview-night gatherings of friends and colleagues, retrieving cold-weather gear from the Armory cloakroom before repairing to nearby bistros for dinner.

In their place was a purpose-built online fair that exhibitors hope will remain in some form as an adjunct to the brick-and-mortar show, whose return is eagerly anticipated.

Never more urgent was the mission of the Winter Show, owned and operated as a fundraiser by East Side House Settlement, which with the onslaught of Covid-19 pivoted to feeding the hungry and, in a push to bridge the digital divide, distributed over 700 internet-connected tablets and hot spots to families in the South Bronx, where, aggravated by shutdowns, the unemployment rate reached 24.7 percent by July 2020.

“The Judgment of Paris” by Lucas Cranach the Elder and workshop (Kronach 1472-1553 Weimar), oil on panel, 24-1/8 by 15-5/8 inches, $450,000. Robert Simon Fine Art, New York City.

East Side House executive director Daniel Diaz recalls, “When the pandemic hit, our board asked how it could focus solely on education and workforce development, our traditional concerns, when people in our community didn’t know where their next meal was coming from. On impulse I said yes to an offer of 43,000 pounds of potatoes from an Idaho farm without knowing where I would receive the shipment five days later.” The upshot was East Side House’s Harvest to Haven Program, which over the past ten months packaged and distributed nearly one million pounds of food. “The program took off after ABC’s World News Tonight with David Muir and Good Morning America featured us. Unilever and Hellmann’s Food Relief Fund wanted to sponsor us. Young graduates of East Side House programs started running Harvest to Haven for us. It grew organically from there,” Diaz said.

Helen Allen, the Winter Show’s executive director, observed, “This year the world was torn apart, but the art world truly came together. While our summer was focused on traffic flow and social distancing guideline policies in anticipation of an in-person event, our fall focused on how to best represent online East Side House and our dealers and the dynamic and eclectic range of works they have.”

Allen and her team worked with developers to create a unique platform that expressed the Winter Show’s distinctive identity and facilitated exchange between buyers and sellers. Allen noted, “We spoke with our colleagues continuously to get their feedback about what they felt was needed to make an online event successful. One of the recurring themes was that it had to be different, be distinctly Winter Show, and they wanted to give their clients myriad opportunities to learn about the work and connect with them. As a result, we came up with virtual galleries, and we incorporated text, Zoom and telephone connections to encourage clients to have direct access with our exhibitors.” According to Diaz, the site’s development was underwritten by East Side House, which offered the platform to exhibitors at a fraction of the fair’s traditional booth rate. And while the VIP Preview, which provided advance access to exhibitors, was structured as a fundraiser for East Side House, the show was otherwise free to visitors.

This late Seventeenth Century spindle-decorated lift-top chest with drawer from what is now Warren, R.I., is illustrated in Art and Industry in Early America; Rhode Island Furniture, 1650-1830 by Patricia Kane et al and was a new acquisition for Bernard & S. Dean Levy Galleries.

Sixty exhibitors, all Winter Show veterans, participated in the online event, which featured virtual booths and related programs, the latter both prerecorded and live. Not everyone liked the site’s more advanced features, some dealers finding 3D galleries cumbersome to construct and some clients finding them hard to navigate. But the showrooms’ essential features worked well, providing clear visuals, substantial cataloging detail and immediate access to exhibitors via phone, email, text or video chat.

Each exhibitor was limited to a total of 35 objects: a maximum of 20 for the initial presentation, plus 15 more for replenishing stock. By necessity, vetting was by photograph. As Allen explained, “We had to do everything remotely in November and December. The committees were looking at works throughout the holidays: reviewing objects, asking questions, looking at condition reports, asking for changes in labeling.” Every object carried a disclaimer from what was called the Online Review Committee and was guaranteed by the exhibitor offering it.

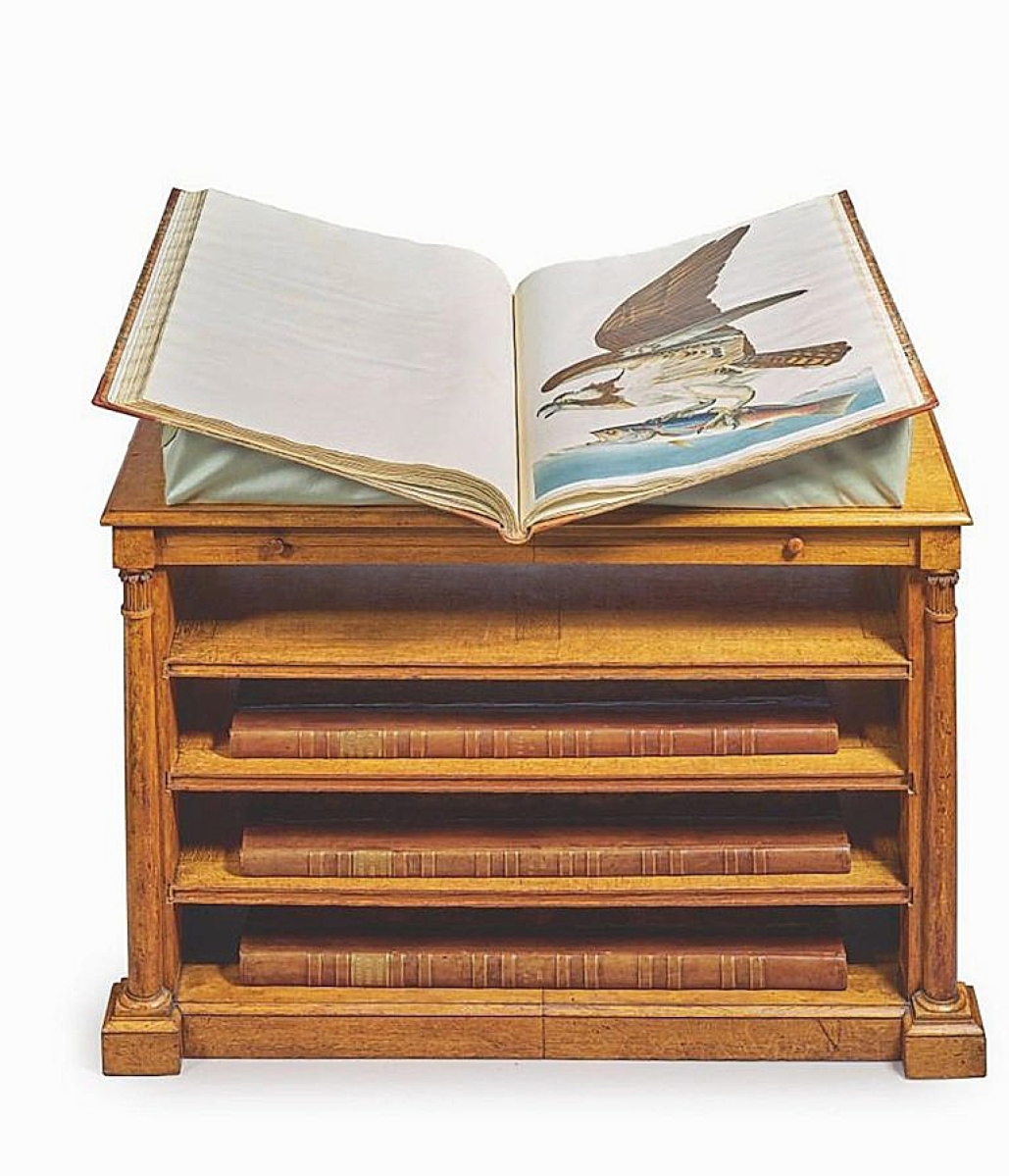

Prices range from around $3,800 for a French Palissy ware fish platter at Cove Landing to $9 million for a four-volume, first-edition printing of The Birds of America by John James Audubon at Arader Galleries of New York and Philadelphia. While most exhibitors posted prices online, some labeled inventory “POR.” An advocate for the latter, Connecticut dealer David Schorsch explained, “I think one reason we’ve done well is that we didn’t post prices, which encouraged people to contact us. I’ve been inundated with queries, which leads to dialogue. We tried to have things that were moderately priced. Our most expensive piece was $165,000.”

Table lamp by Tiffany Studios, 1902-04, with Peacock shade and patinated bronze base inset with original Tiffany turtle-back tiles. Lillian Nassau, Ltd.

Led by Robert Aronson, the Delftware specialist Aronson of Amsterdam maintains one of the field’s most imaginative and ambitious online presences. The company’s website joins articles and videos with an online bookstore and an augmented-reality gallery. The dealer’s January 11 virtual presentation to the Connecticut Ceramics Circle netted more than 200 new subscribers to the company’s informative newsletter. Aronson’s 2020 catalog, Delftware: Between Heaven and Earth, Sources of Inspiration, features a detailed look at some of the pieces on view at the Winter Show.

Aronson believes in using technology to cultivate a following and promote his inventory. He says, “Posting objects online to the virtual show was not as simple and straightforward as writing a label and bringing pieces to the fair, but the Winter Show explained the process well.” As for the modern marketing mix, he says, “It’s the combination that works. We’re sending out newsletters, keeping our website updated and post every day on Instagram, which plays a very important role in our business nowadays.”

Bernard & S. Dean Levy Galleries, which led guests on a virtual tour of its new showrooms on West 17th Street in Manhattan, unveiled a late Seventeenth Century lift-top chest with spindle decoration from what is now Warren, R.I. A new acquisition, it is illustrated in Art and Industry in Early America: Rhode Island Furniture, 1650-1830 by Patricia Kane et al. Two Boston pieces in the dealer’s space were the 1750 Tate-Welch Queen Anne desk-and-bookcase, which Frank Levy recalled seeing many years ago in North Carolina with his late grandfather, Bernard, and a 1795 Boston sideboard attributed to John and Thomas Seymour. Levy sold a circa 1810 Federal New York trick-leg card table attributed to Duncan Phyfe and a circa 1790 Connecticut comb-back Windsor armchair.

Among several exhibitors’ talks was one by Walter Arader, director of Arader Galleries in New York City.

Nathan Liverant and Son affixed a sold sticker to a bonnet-top highboy priced $70,000. The cherry case piece was made in Connecticut’s Housatonic River Valley between 1760 and 1785 and descended in the family of its first owner, Connecticut statesman Roger Sherman. The Connecticut dealers acquired the highboy at auction in New Hampshire in 1994 and recently reclaimed it from a downsizing client. Liverant also sold an 1820 needlework sampler by Lucy C. Jillson of Pelham, Mass., whose teacher, identified as “M. Southworth Instructress,” was possibly Mary Southworth; a circa 1700-30 William and Mary bannister-back side chair formerly in the Bolles collection, sold to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1909 and included in the pioneering Hudson-Fulton exhibition; and an early Eighteenth Century William and Mary ladder-back highchair.

Taylor Thistlethwaite noted the “rich finish, large original brasses and exceptionally elegant stance” of a circa 1760 Massachusetts high chest of drawers. Israel Sack, Inc., published the $78,000 piece in 1969. The Virginia dealer sold a circa 1750 chest of drawers from Virginia’s Tidewater region; a diminutive Massachusetts mahogany tea table, probably from Essex, Mass., circa 1750-60; and a late Eighteenth Century blocked-end and serpentine-front chest of drawers.

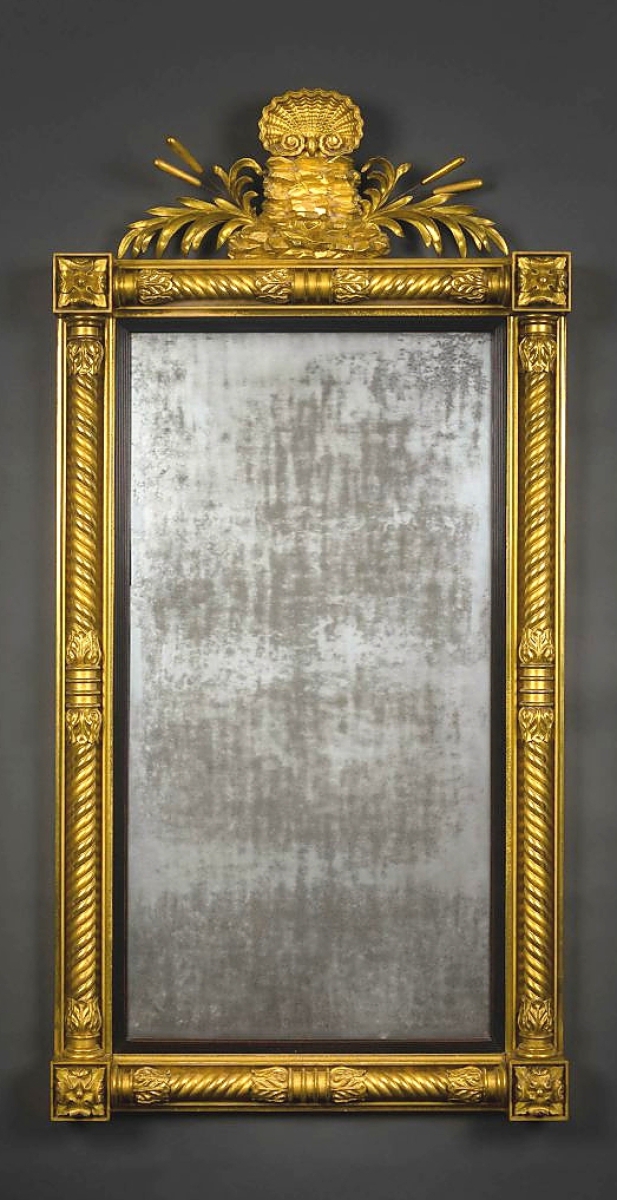

A handsome rarity at Hirschl & Adler Galleries was a circa 1820 pier mirror, $125,000, attributed to Boston looking-glass maker John Doggett. Prominent in the exhibition “Boston in the Age of Neo-Classicism, 1810-1840,” it had recently been reacquired by the New York dealer.

Delftware figure of a man pushing a sleigh, circa 1770, height 5½ inches. Aronson of Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

English furniture and accessories ranged from a miscellany of relatively affordable pieces at Cove Landing, which sold a George IV calamander occasional table, English Regency papier mache footbath and a George III mahogany tea caddy, to the museum quality offerings of Apter-Fredericks, which posted receipts of $4.7 million in a concurrent auction of gallery stock at Christie’s London.

Bernard Goldberg Fine Art mounted a solo show of the work of little-known Modernist painter Wood Gaylor, who exhibited at Edith Halpert’s Downtown Gallery and is the subject of a retrospective exhibition at the Hecksher Museum of Art through May 23. Goldberg’s early sales included Gaylor’s “Liberty Bonds, U.S.S. Recruit,” an oil on canvas of 1924.

“We had ten sales as of Saturday and another five pieces on hold or out on approval,” David Schorsch said after the fair’s first weekend. The Connecticut specialist in Americana and his partner, Eileen M. Smiles, wrote up a Schimmel eagle with a 21¼-inch wingspan; Sturtevant J. Hamblin’s circa 1845 portrait of a boy in blue holding a hat and whip; a rare Indian figurehead model of about 1830; a Native American basket formerly in the Palley collection; a birth and baptismal certificate by Christian Mertel, a.k.a. “The C.M. Artist”; a theorem on velvet; and a heart-shaped iron trivet dated 1832. Schorsch called a vibrantly decorated crooked-neck coffee pot originally owned by Elizabeth Hotsetter-Huber of Lancaster County, Penn., and from the Filley tin shop of Philadelphia, circa 1825-50, “a personal favorite,” noting, “we have enthusiastically bought and sold this masterpiece on three separate occasions over the past two decades.”

Italian painter Afro Basaldella designed this gold bangle set with rubies and diamonds. It was made in the Rome workshop of Diderico Gherardi for Mario Masenza around 1960. Didier, Ltd., London.

German folk art made an appearance at Kelly Kinzle, who parted with a whimsically carved Black Forest hall tree of about 1870. The Pennsylvania dealer also wrote up a dated 1853 parade drum depicting West Point and bearing the label of New York City maker William Seele Tompkins.

London dealer Robert Young likewise had success with a circa 1860 German Noah’s Ark toy. Young’s other sales included an English vernacular hunting trophy, a carved and painted Northern European portrait bust, a pair of owl finials and a circa 1620 English tankard of turned wood.

Michele Beiny, a New York expert in ceramics and glass, sold a rare French faience panel, most likely a table top and probably made around 1730 in Rouen. Other sales included Modern and contemporary glass by the American glass artists John Littleton, Kate Vogel and William Morris.

Visitors missed the burbling fountain and hand-painted mural that are regular features of Barbara Israel’s displays. Instead, the expert in garden sculpture charmed viewers with photos of objects shot in evocative, natural settings. Favorite pieces ranged from the delightful “Frog Baby” fountain by Edward Henry Berge, a bargain at $6,500, to a marked J.W. Fiske Iron Works stork fountain, $17,500, and a Wood & Perot cast iron retriever, $28,500.

Described as “a masterpiece of Persian weaving from the post-classical period,” this late Eighteenth Century carpet measures roughly 29 by 10½ feet and was $220,000 at Peter Pap Oriental Rugs, Dublin, N.H., and San Francisco.

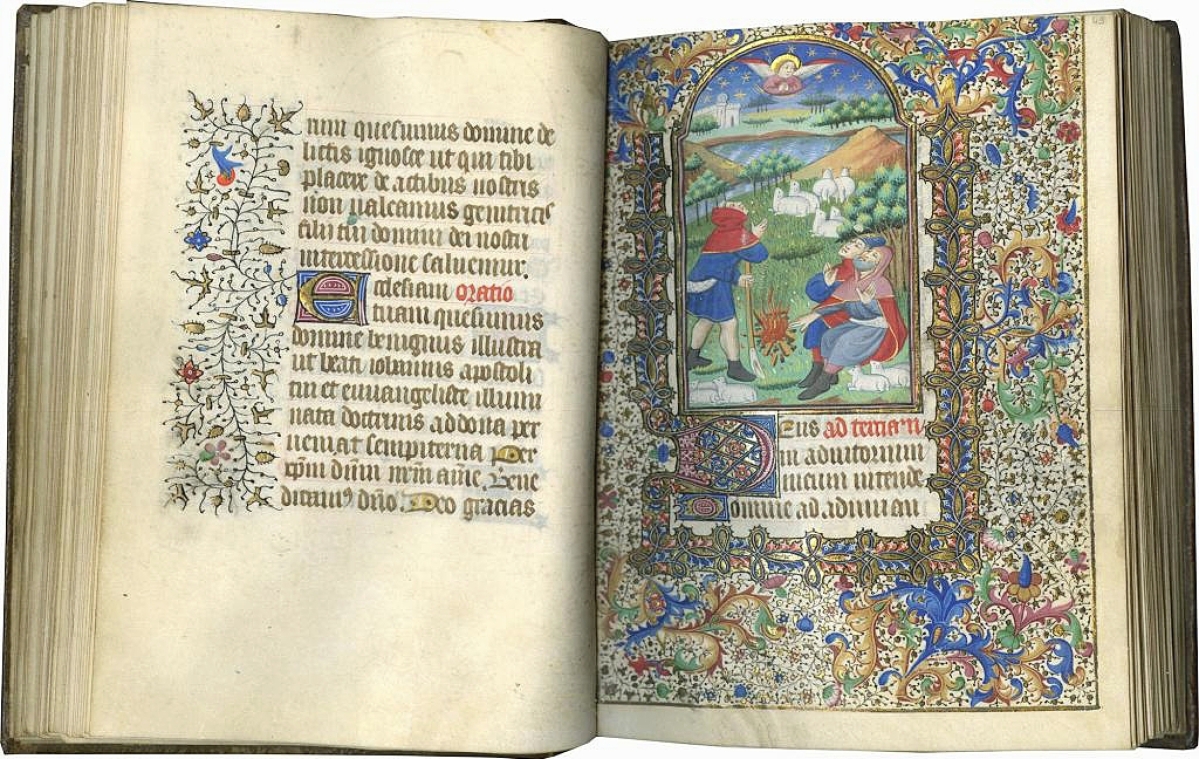

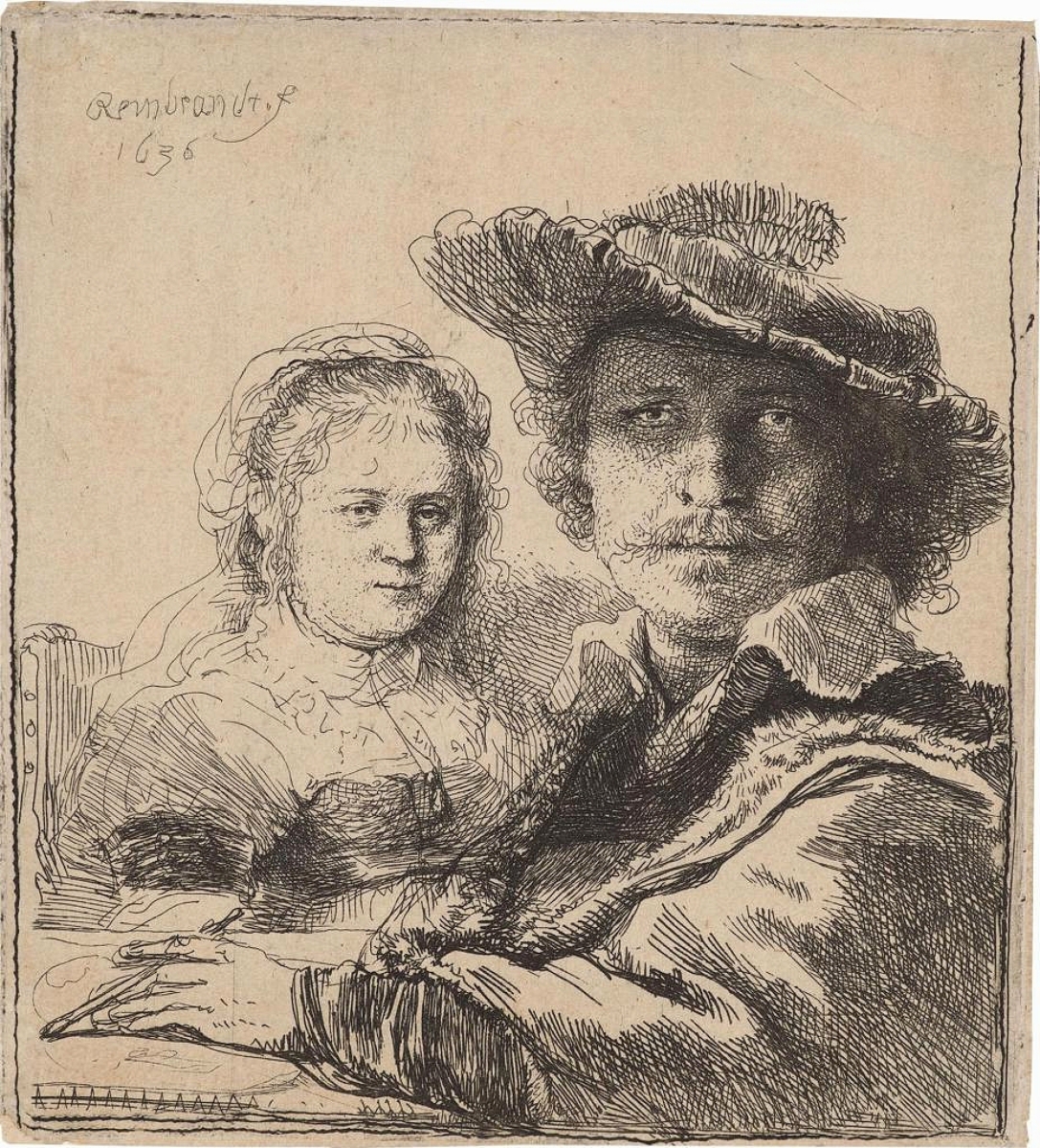

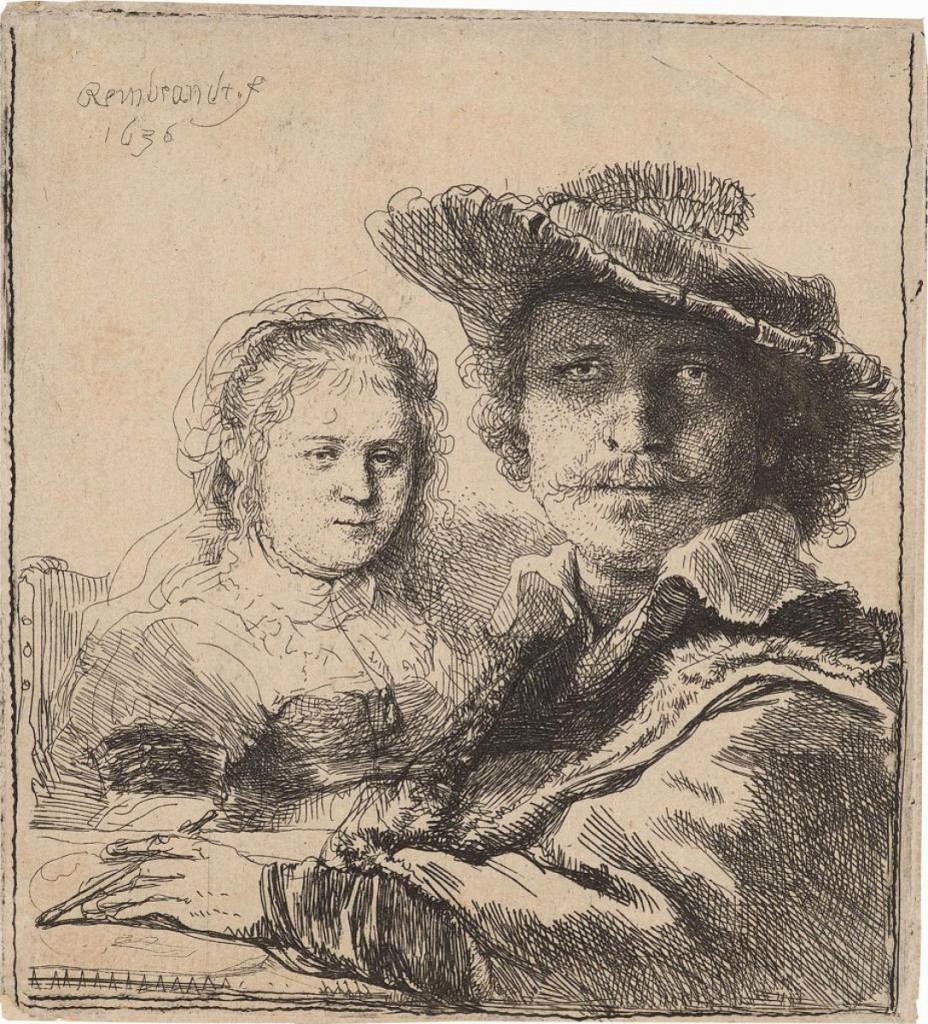

Les Enluminures of Chicago, New York and Paris confirmed the sale of a circa 1450 Book of Hours, $125,000, ornamented by an anonymous Parisian illuminator, while Hill-Stone, Inc., parted with the small but sensational Rembrandt self-portrait with his adored wife, Saskia, circa 1636.

Silver dealers S.J. Shrubsole and Spencer-Marks had good news. Shrubsole sold a 1681 Charles II silver sugar box with engraved coat of arms by Alexander Roode of London and featured a captivating “black silver” and enameled coffee pot, $110,000. Shrubsole president Tim Martin noted that the piece is one of eight “after-dinner” coffee pots, all featuring enameling and unusual hardstone mounts, that Tiffany & Company displayed at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893.

Chicago Exposition pieces were also a draw at Spencer-Marks, which sold related silver and copper Terrapin and Snail vases, unique pieces designed by John T. Curran for Tiffany & Company’s Chicago display. “We had institutional interest in the vases, but a private buyer acted first. The seller is very happy the pieces are staying together,” Spencer Gordon said of the works off the market since 1893. Other Spencer-Marks sales included a sterling silver fruit or punch bowl with undertray by Mary Knight/Karl Leinonen, circa 1907; a Whiting sterling silver and mixed-metal tête-à-tête tea service, circa 1880; a circa 1880 Aesthetic Movement silver vase by George C. Shreve & Co.; a rare sterling and oyster shell Arts and Crafts lamp by Clemens Friedell, circa 1920; and a 1918 Gorham special-order centerpiece with “Baronial” decoration.

Rembrandt’s tiny print of himself with his beloved wife, Saskia, sold to a private collector at Hill-Stone, Inc. The 1636 etching is from the first of three printings.

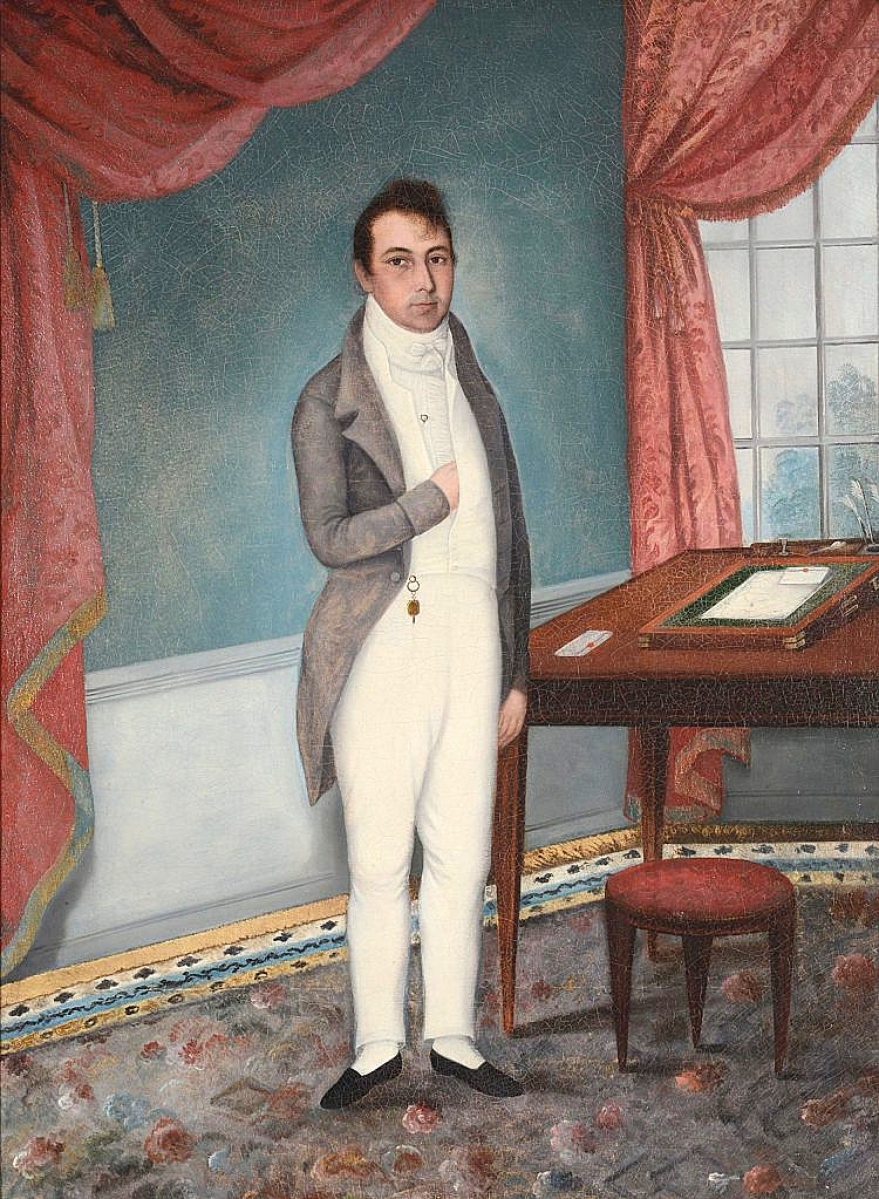

Chinese export art was one of the fair’s strong suits. Martyn Gregory, the leading authority on China trade pictures, captivated visitors with panoramic landscapes, botanicals and a choice oil on canvas portrait painted in Canton around 1810, possibly by Spoilum, of John Smith Crary, a Palmer family descendant who was born in Stonington, Conn. Crary managed his silk-importing business from New York and was the first president of the New York, Providence and Boston Railroad Company.

Ralph M. Chait Galleries boasted two exceptional Chinese reverse paintings on glass for the Western market. One, $35,000, depicts a scene from Shakespeare; the other, $26,000, a moral allegory. Both are illustrated in Crossman’s The China Trade.

The research-driven firm Cohen & Cohen shed new light on a circa 1740 armorial charger, $60,000, painted in grisaille and inspired by a 1737 print engraved by Jean Moyreau after a painting by Philips Wouwerman. Study by Washington and Lee University curator Ron Fuchs led to the discovery that a 16-inch-tall porcelain figure of a woman, $235,000, in Cohen & Cohen’s booth most likely represents a member of Frankfurt’s Sixteenth Century Jewish community and was possibly modeled after a print by Caspar Luyken.

Spencer Marks sold to a private collector the silver and copper Terrapin vase, a unique Tiffany & Company piece exhibited at the 1893 Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition, where the company also featured related Snail and Owl vases. The whereabouts of the Terrapin vase was unknown by Tiffany scholar John Loring as recently as 2000.

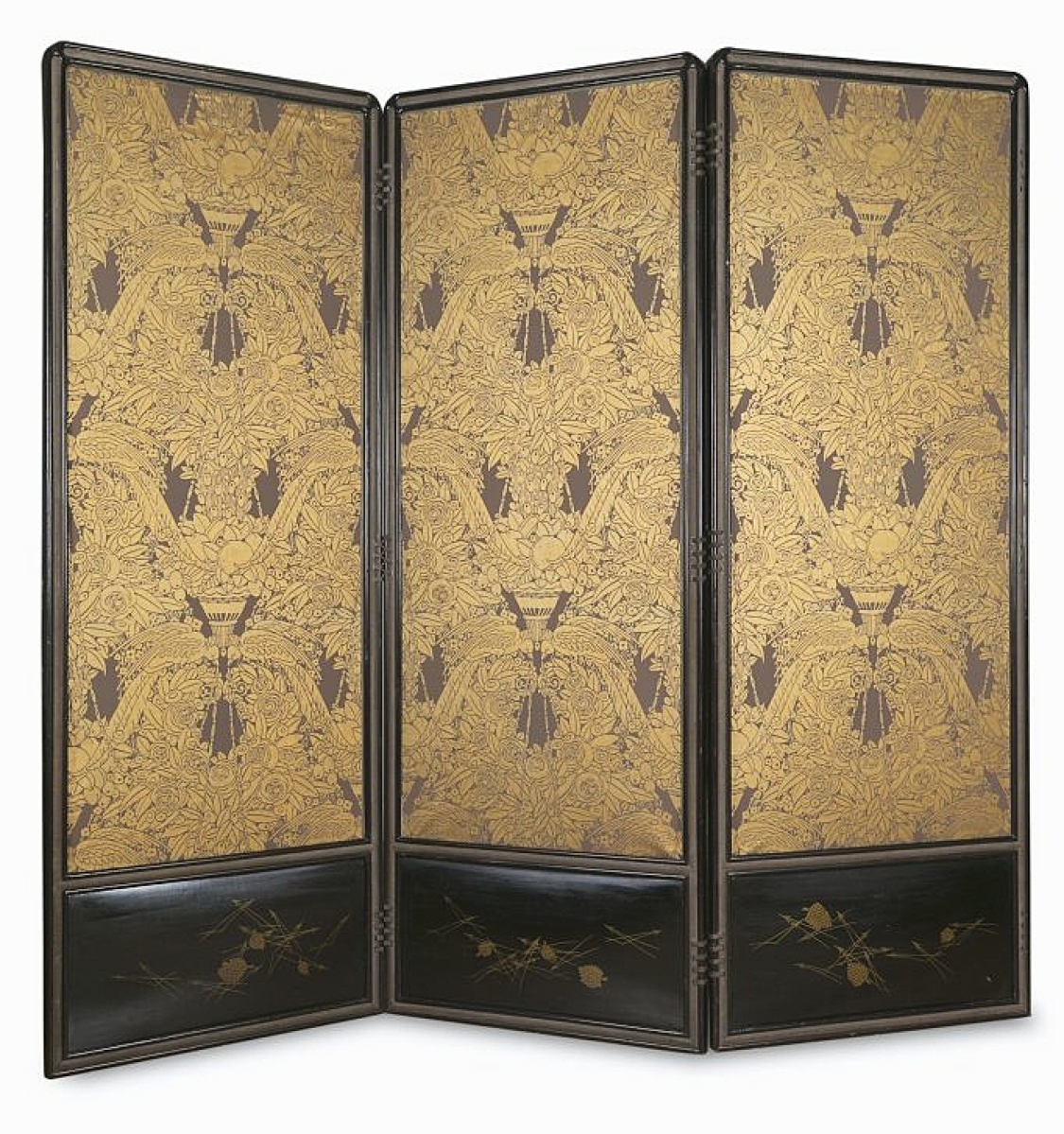

To mark her 40th year participating in the Winter Show, Japanese art authority Joan B. Mirviss presented the curated display “Masterworks of Modern Japanese Porcelain.” Early sales from her online stand included ceramic sculpture and functional objects by Kondo Takahiro, Fukumoto Fuku, Inaba Chikako, Kondo Takahiro, Takegoshi Jun, Fujimoto Yoshimichi (Nodo) and Yagi Akira.

“In a normal year, East Side House derives between $600,000 and $800,000 in financial support from the Winter Show. It won’t be anything close to that this year. Creating the online fair was an investment for East Side House. We own the Winter Show and want it to be successful going forward. Without the Winter Show, we could not continue feeding 5,000 people a week,” Diaz said.

Allen noted, “Given the time we had to do it, I’m excited about what we achieved this year and hope we can continue aspects of it. The virtual show gives dealers a chance to broaden their audience. Imagine sending a link to a friend in Australia who can’t attend the show. This opens up the prospect for a much bigger engagement.”

East Side House Settlement is at 337 Alexander Avenue in the Bronx, N.Y. To learn about its programs or to make a gift, go to www.eastsidehouse.org or call 718-665-5250. For more on the show, visit www.thewintershow.org.

_por.jpg)