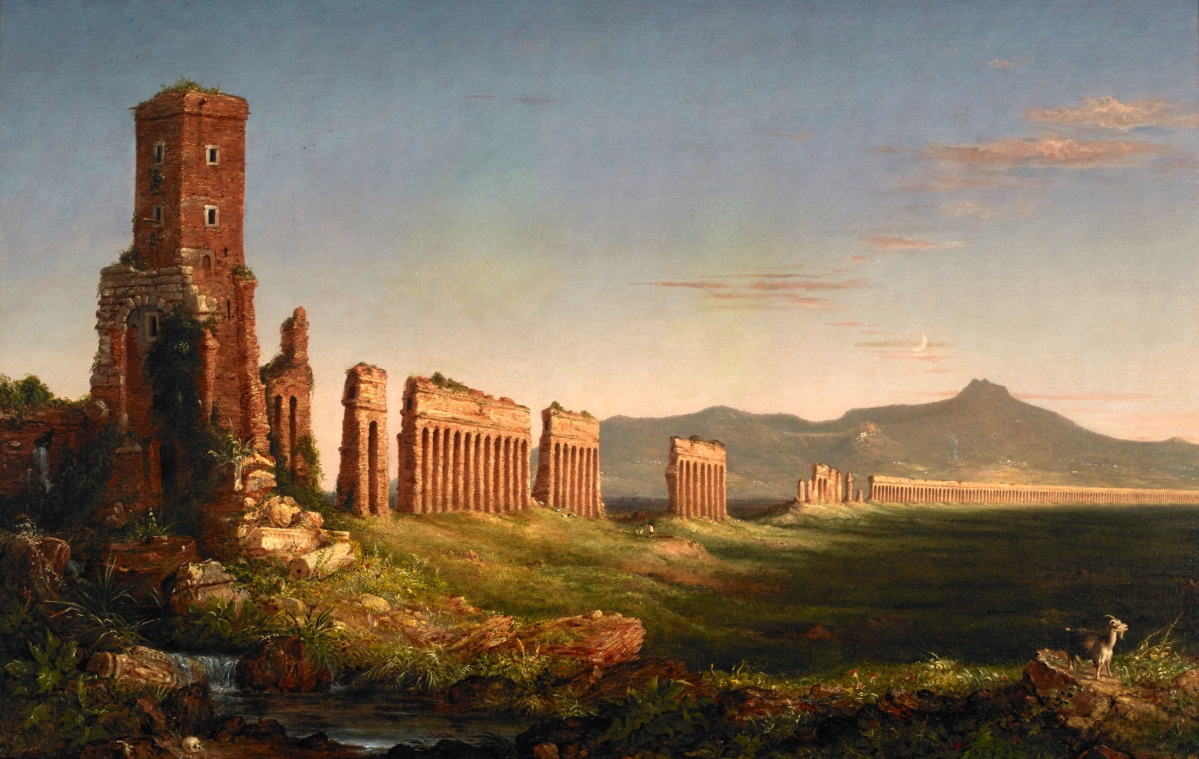

“Aqueduct near Rome” by Thomas Cole, 1832. Oil on canvas, 45 by 68-1/8 inches. Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, Washington University, St Louis.

By Jessica Skwire Routhier

NEW YORK CITY – Thomas Cole’s sublime landscape paintings defined American art for more than a generation in the mid-Nineteenth Century. Blessed with both generous skills and a singular vision, he helped to elevate American scenery to a subject worthy for art, as well as landscape painting itself to an art form that garnered the same respect as history painting and portraiture. We think of him today as the “founder” of the so-called Hudson River School of landscape painters: contemporaries, students and imitators who painted superlative views of the American wilderness, based in reality but laden with conscious and subconscious ideologies about nation, nature, race, progress and conflict.

“Thomas Cole’s Journey: Atlantic Crossings” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, January 30-May 13, explores how the residue of Cole’s early life, working in British factories before emigrating to America at age 17, is manifest in his paintings in many ways. More importantly, however, it also examines a career-defining journey back to England, and then to France and Italy, from 1829 to 1832.

“The journey he took,” says Elizabeth Mankin Kornhauser of the Met, “the early roots and then the journey back – really enriched not only his painting technique but his intellectual approach to depicting the American landscape.” The exhibition will travel to London’s National Gallery in June, in a sense repeating Cole’s own transatlantic journeys.

In an essay for the exhibition catalog, co-curator Tim Barringer, also of the Met, describes how Cole was born in 1801 in Bolton-le-Moors, in Lancashire, during the height of the Industrial Revolution. The economy in Bolton, which is near the industrial center of Manchester, was burgeoning at the time, with bustling factories and a growing population. Joseph Mallord William Turner’s watercolor of Leeds, just 60 miles away, shows how, by this time, factories were as much an element of the northern landscape as the moors.

In an essay for the exhibition catalog, co-curator Tim Barringer, also of the Met, describes how Cole was born in 1801 in Bolton-le-Moors, in Lancashire, during the height of the Industrial Revolution. The economy in Bolton, which is near the industrial center of Manchester, was burgeoning at the time, with bustling factories and a growing population. Joseph Mallord William Turner’s watercolor of Leeds, just 60 miles away, shows how, by this time, factories were as much an element of the northern landscape as the moors.

The new economy benefited locals unequally, however; as Cole’s father struggled to adapt to mechanization and suffered various failed ventures, others outwardly protested the use of machines to replace human labor. Bolton was the site of a violent uprising in 1812 led by the Luddites, whose quasi-mythical leader Ned Ludd was depicted in a contemporaneous lithograph, clad in the calico fabric that the new factories were producing en masse.

In fact, the young Cole’s first job, at 14, was as an engraver for a factory that produced these printed cottons; he was responsible for incising designs onto the wooden blocks used to stamp patterns onto the fabric. Within a few years he became an engraver’s assistant for a company that produced the landscape prints that were increasingly popular in Britain at the time. In this context, Barringer argues, Cole would have had occasion to view the rapid industrialization of his native Lancashire in a new way. Along with the economic opportunities that new industries offered came wide-scale despoliation of Britain’s natural beauties, which were only starting to be fully appreciated. Just as Turner had envisioned the city of Leeds through the bifurcated lens of wild moors and belching factories, Cole would, throughout his career, be torn between his ardent preservationism – implanted while he was still in England – and the urban populations and opportunities that made his livelihood possible.

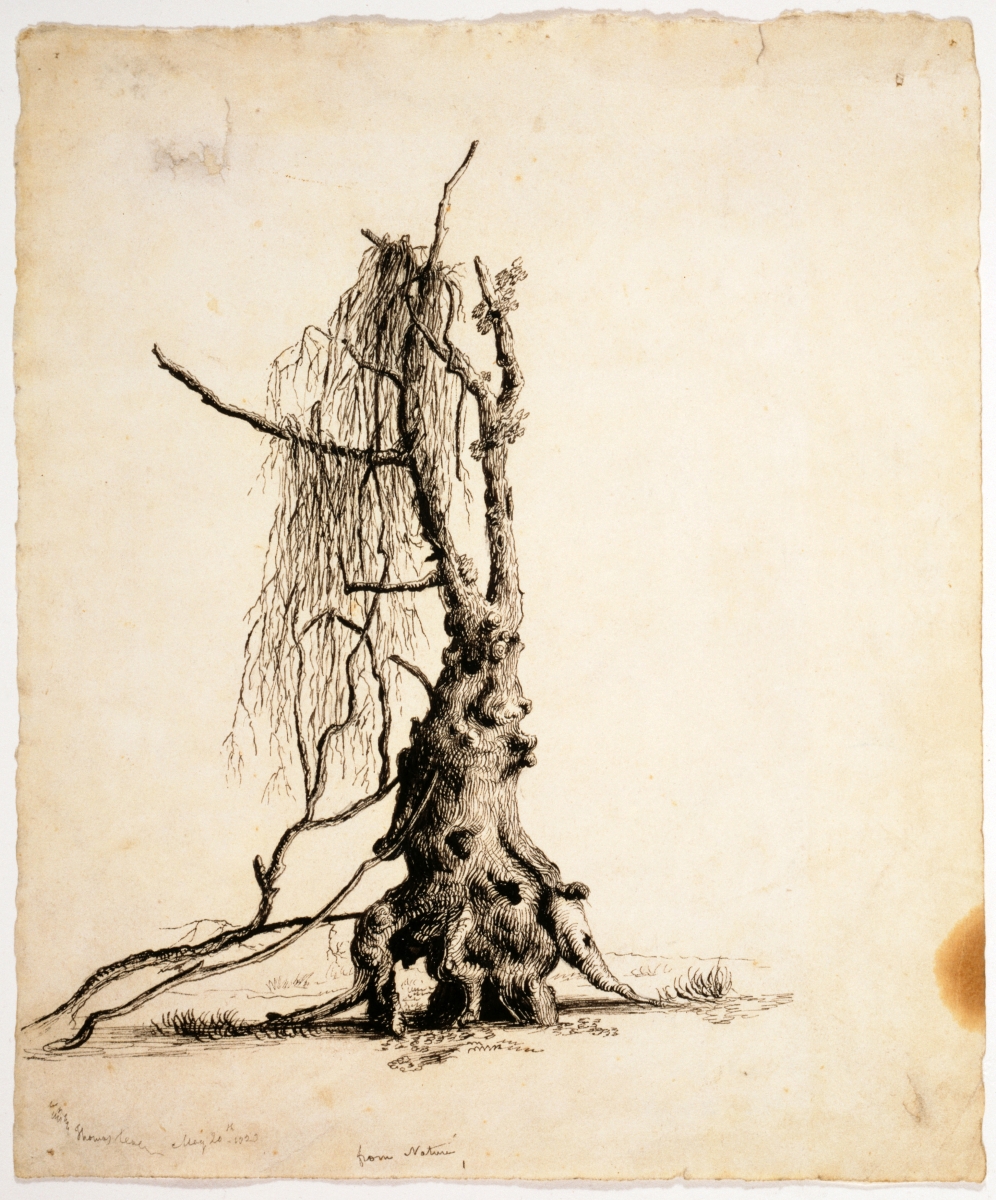

Cole emigrated to America with his parents and sisters in 1818, and soon entered a relatively peripatetic existence as he strove first to find steady employment and then to establish himself as a serious, independent painter. (An excellent chronology in the catalog, by research assistant Shannon Vittoria, tracks his movements at this time and beyond.) In addition to his professional work, Cole also kept copious sketchbooks, featuring painstaking studies of nature. Twisted and gnarled tree trunks were a favorite subject, probably in emulation of the Seventeenth Century Italian painter Salvator Rosa, who was known for the so-called “sublime” (wild and somewhat terrifying) effects of his landscapes.

“View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, after a Thunderstorm — The Oxbow” by Thomas Cole, 1836. Oil on canvas, 51½ by 76 inches. Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Mrs Russell Sage, 1908. Image ©The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Cole employed the blasted-tree motif in his early full-scale exhibition pictures like “View of Round-Top in the Catskill Mountains” and “Scene from ‘Last of the Mohicans,'” astonishingly mature works for a 26-year-old immigrant with no formal artistic training. The works show the influence of not only Rosa but also Claude Lorrain – the other European “old master” of landscape painting, whose works embodied the more cultivated and tranquil “beautiful” mode – but are distinguished by Cole’s inimitable style and because of his resolute choice of American subjects, both real and fictional.

By 1829, Cole had fully committed himself not only to his art but also to his adopted country, setting up residence in New York and finding rich subject matter along the banks of the Hudson River. Even when his landscapes were of the imaginative variety – the pendant pair “The Garden of Eden” and “Expulsion from the Garden of Eden” of 1828 being a key example – American sensibilities pervade. The sense of America as a “new Eden,” in danger of destruction, was pervasive at the time, and Cole himself would harness that metaphor in words as well as paint in his influential “Essay on American Scenery” in 1835. It may seem paradoxical, then, that in order to advance his career as an American artist, he chose to travel back across the Atlantic, beginning in Britain, and that in fact the sale of the two “Eden” paintings helped him to finance that trip.

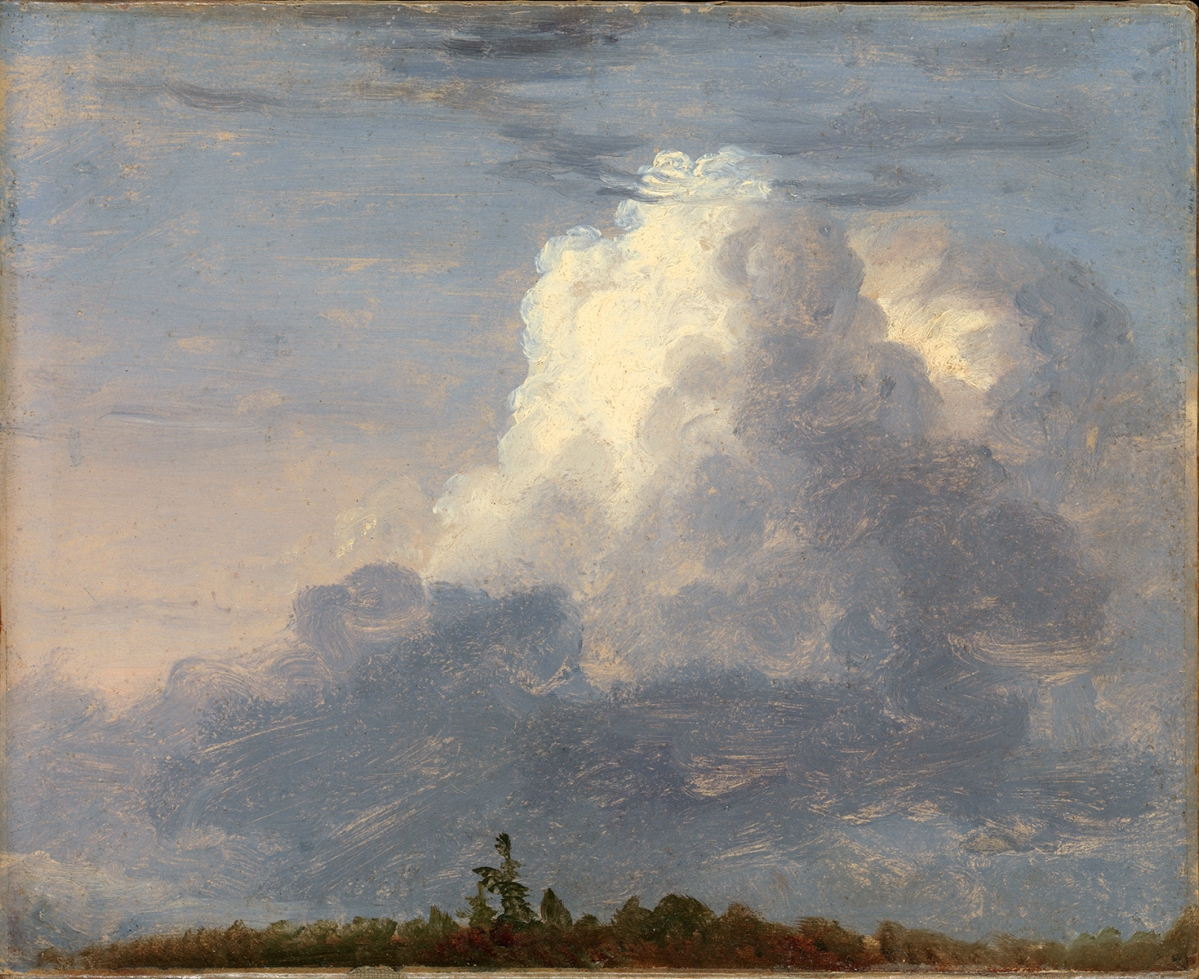

The Met’s exhibition accomplishes the remarkable feat of bringing together many of the widely lauded paintings that Cole is known to have seen, and been greatly influenced by, in London’s museums. These include works like Lorrain’s “Seaport with the Embarkation of Saint Ursula” and John Constable’s “Hadleigh Castle,” both of which, Barringer points out, feature architectural infrastructures that would later appear, in an altered form, in Cole’s five-canvas series “The Course of Empire”; as well as more atmospheric works by Constable and by Turner, contemporary artists that he visited in their studios and discussed plein air painting with. The dramatic effects of sky, wind and clouds for which Turner and Constable were known would later reappear powerfully in “The Oxbow” and many of Cole’s other later works.

An excellent catalog essay by Christopher Riopelle, curator at the National Gallery, follows that thread of plein air painting into the second half of Cole’s trip – to Italy. “All of the artists in Europe and American gathered in Rome and Florence … and did plein air oil studies,” Kornhauser explains. The technique is such a standard of landscape painting today that it can be difficult to appreciate the sea-change that it brought to Cole, who, of course, had always made studies directly from nature. But in fact, before Italy, those studies had always been in graphite or pen and ink rather than oil. Riopelle shows how the small-scale oil study, done onsite, allowed artists to work out complicated compositional details as well as effects of color with the same materials they used in the studio. The process of building a full-scale exhibition picture like Cole’s “Aqueduct Near Rome” or “View of Florence from San Miniato,” then, was in part one of seaming together those smaller studies, resulting in a final work whose every detail is richly complete.

“The Course of the Empire: The Consummation of Empire” by Thomas Cole (1801–1848), 1835–36. Oil on canvas, 51¼ by 76 inches. New-York Historical Society, gift of the New-York Gallery of the Fine Arts, 1858. Digital image created by Oppenheimer Editions.

Cole “triumphantly embraced and repatriated to America” this new technique of oil painting, Riopelle writes, teaching it to his students and followers like Frederic Edwin Church and Asher B. Durand. “We contend that had Cole not done this,” Kornhauser says, “the Hudson River School would not have launched as forcefully as it did, without this journey of Cole’s.”

The grand culmination of the Met’s exhibition are two iconic, large-scale paintings Cole completed nearly simultaneously shortly after his return from abroad: the Met’s own “View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, after a Thunderstorm – The Oxbow” and New-York Historical Society’s “Consummation of Empire,” the centerpiece of “The Course of Empire” series. Although both paintings have drawn the attention of critics and scholars since the moment of their creation, Kornhauser argues that they remain “understudied.” “The ‘Oxbow’ has hardly ever been lent by the Met, ever, so it was never part of these larger exhibitions that discussed the Hudson River School in general.” In particular, she believes that both of these monumental works merit examination through the lens of the relatively new field of ecocriticism, which explores how producers of culture both portrayed and influenced attitudes toward nature.

Cole was already a burgeoning preservationist before his trip, but it seems that the extended period traveling in urban European locales reinforced such feelings for him. He was fond of Florence but taken aback by the congestion and squalor in London and Rome; upon his return to America he was horrified to see the railroad encroaching upon the virgin landscapes that he had known and painted in his beloved Catskills. Much of this is explicit in his correspondence and journal entries, as well as his famous proto-environmentalist “Essay on American Scenery.”

“He’s constantly ranting about the new evidence of deforestation and the industrial presence in the American landscape upon his return from his journey in 1832,” Kornhauser says. “He also rails against the presidency of Andrew Jackson. He’s deeply opposed to expansionist policies and the encouragement of industrialization.”

This philosophy is readily apparent in both “The Oxbow” and “The Course of Empire.” In the former, the canvas is dramatically split between a wild, untamed wilderness on the left and a dramatically altered one on the right, punctuated by puffs of manufactured smoke. In the latter, five paintings detail the rise and fall of a great civilization, from innocent beginnings through triumphant growth to self-implosion; in each canvas, the sun tracks its course through the sky, so that in the final canvas, “Desolation,” it has set and a chill moon has risen. “Consummation” is the midday scene, the light shining brightly on the riches and delights of an empire at its height; but because the paintings were meant to be viewed together, we know what its fate will be.

These are not new observations, but Kornhauser’s situating the analysis within the discipline of ecocriticism – both in the exhibition itself as well as the accompanying catalog and programming – is. So, too, is the recent discovery that “The Oxbow” actually bears underdrawings related to “The Consummation of Empire,” discernable through x-radiography. “We were able to demonstrate that while he was working on those paintings at the same time,” says Kornhauser, “he embedded the same message to the American public”: that America most do better; must find “a way to retain many of the sublime aspects of the landscape and not move so rapidly and so harshly to alter the land out of greed.”

There are other covert messages in “The Oxbow” as well. Kornhauser points out, as other scholars have in the past, that areas of clear-cutting on the distant hills give the effect of Hebraic letters writ large on the American landscape, like a kind of warning from the heavens. She also notes the placement of two figures in the lower foreground of each painting: in “The Oxbow,” a self-portrait of the artist at his easel, and in “Consummation of Empire,” at nearly the same spot in the canvas, a bearded philosopher, his hand thoughtfully tapping his chin. Both act as critics, or at least witnesses, to the scenes depicted, stressing the important role of artists and writers in making sense of humanity’s evolving relationship to nature.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art is at 1000 Fifth Avenue. For information, 212-535-7710 or metmuseum.org.

Jessica Skwire Routhier is managing editor of Panorama , the journal of the Association of Historians of American Art. She lives in South Portland, Maine.