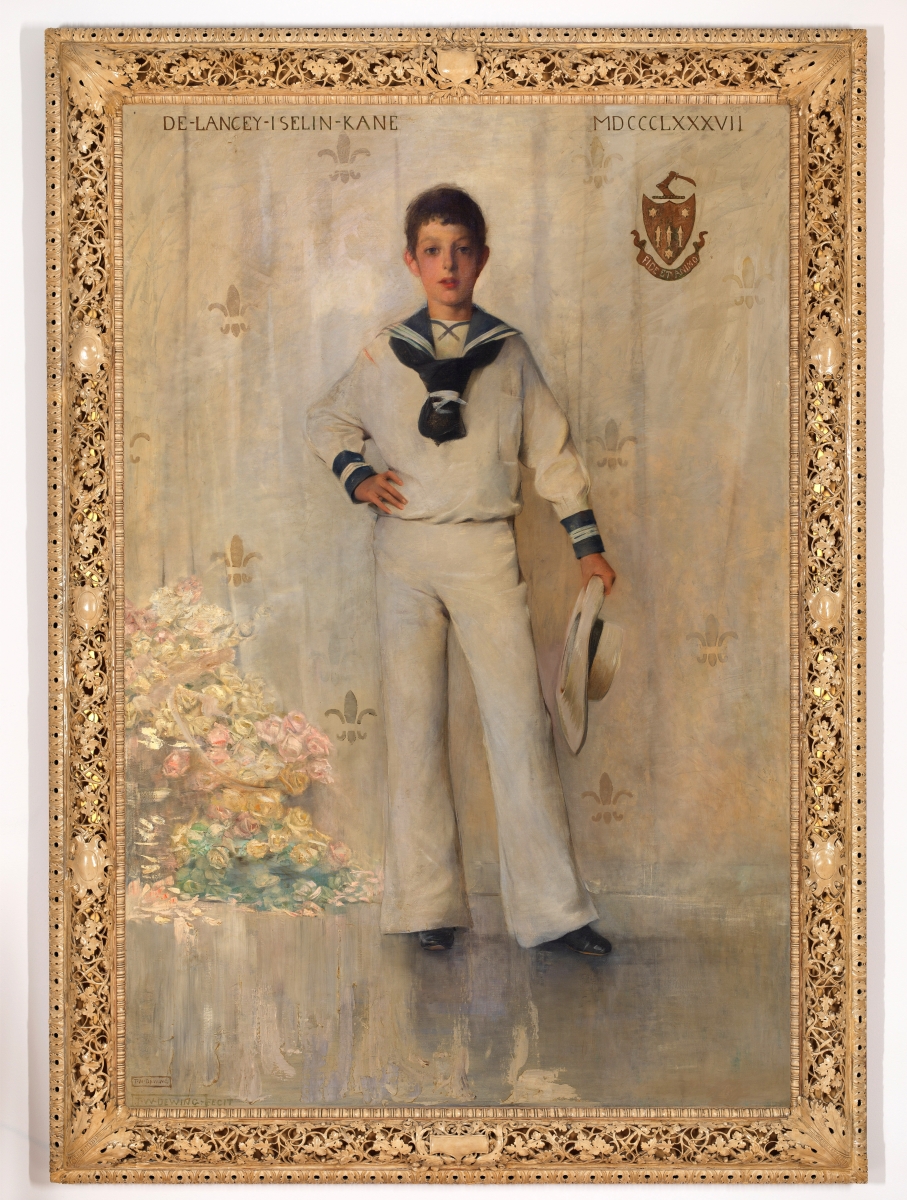

“A Garden,” 1883. Oil on canvas, 16 by 40 inches. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; bequest of George H. Webster, 1934.

By Laura Beach

ALEXANDRIA, VA. – To gaze upon a work by Thomas Wilmer Dewing (1851-1938) is to be drawn into a waking dream. Whether in oil or pastel, reveries by the Boston-born aesthete typically depict languid, remote, ethereal women. In groups, they form friezes in dusky, ambiguous landscapes. Solitary in domestic interiors, they are contemplative, perhaps resentful of their captivity or burdened by ennui.

The irony, as told by scholar Susan A. Hobbs in her definitive study Thomas Wilmer Dewing: Beauty into Art, a two-volume catalogue raisonné with Shoshanna Abeles, is that Dewing’s idealized dreamscapes have always been abstract enough to avoid precise definition, an asset when it came to recruiting buyers who saw in them what they wished, whether vanguard experimentalism, calls to moral purity or entry to a world of cultural refinement. On the artist’s subtlety and originality, his critics largely agreed. As Hobbs explains, “This quality of uniqueness emanated from almost imperceptible tensions that run through his compositions, as well as the intricacy of their painted surfaces.”

Dewing found freedom in his constrained subject matter, much as a bard finds liberation in the discipline of a sonnet. Within these self-imposed limits, Dewing, as the art critic Royal Cortissoz put it, “showed a vast will to do what he believed…” Structure allowed Dewing’s work to evolve with the times while seeming timeless. Broadly speaking a Tonalist who experimented with Impressionism, Dewing absorbed the tenants of English Aestheticism early in his career and was especially influenced by Whistler. By the time he was rediscovered in the mid-Twentieth Century, a handful of connoisseurs detected in his work an otherworldliness bordering on the surreal.

Dewing’s fortunes and those of his chief patron, Charles Lang Freer (1854-1919), were intertwined. It has been the life’s work of Hobbs, former curator of American art at the Smithsonian Museum of American Art and the Freer Gallery of Art, to tell Dewing’s story, a task she performs with unsurpassed skill in a narrative both engaging and authoritative. Work by work, the scholar builds a picture of the artist and his milieu, a portrait so comprehensive we feel we are part of Dewing’s sophisticated circle of artists and collectors who congregated in New York, Boston, London, Paris and Cornish, N.H., where the artist and his wife, painter Maria Oakey Dewing, were influential members of the summer art colony.

Hobbs’ story begins in 1974, when the scholar, who earned her doctorate in art history at Cornell, took up her joint curatorial post in Washington, DC. “Works by Dewing, Whistler, Dwight Tryon, Abbott Thayer and a group Charles Freer called ‘the miscellaneous Americans’ were kept on racks in the Freer’s basement. It was my job as a newly-minted curator to take people down to look at them. I was embarrassed to have none of our American collection on view for the 1976 Bicentennial,” she recalls with a wince.

In 1977, Hobbs began researching the Freer’s American collection, building upon a brief checklist she found there when she arrived. One of her first projects was a booklet on the museum’s celebrated Peacock Room by Whistler, the artist who most influenced the collecting tastes of Charles Lang Freer and a mutual friend of both Dewing and his principal patron. With 42 oils and watercolors by Dewing in the Freer collection from which to draw, Hobbs thought she might have the beginnings of a catalogue raisonné.

Hobbs’ progress was on view in 1996 when with curator Barbara Gallati she published The Art of Thomas Wilmer Dewing: Beauty Reconfigured, the catalogue to the landmark exhibition that traveled from the Brooklyn Museum to the National Museum of American Art and the Detroit Institute of Arts. The collector Richard Manoogian (b 1936), like Freer from the Detroit area, helped fund the effort.

Art dealer Jonathan Boos, then a curator and advisor to the Manoogian Collection, assisted in the 1996 project. Of Hobbs’ latest venture, he says, “These two volumes are an incredible testament to the importance of Thomas Wilmer Dewing as an American artist and a great contribution to the history of American art of the late Nineteenth and early Twentieth Centuries. Susan and her team took the time to get every aspect of this important project wonderfully right.”

Hobbs cites the contributions of dealer Warren Adelson, whose early support of the catalogue allowed her to recruit the invaluable Abeles as her chief assistant and later project manager. Through Adelson, Hobbs also became familiar with the circle of Dewing enthusiasts who rediscovered the artist in the mid-Twentieth Century.

The complexity and expense of the catalogue effort warranted its incorporation as a tax-free 501(c)(3) entity. Serving with Hobbs on the project’s board of directors are Dewing expert and Freer curator Lee Glazer; D. Frederick Baker, author of the William Merritt Chase catalogue raisonné; Maria Dewing Rooney, a great-granddaughter of the artist; Austin A.J. Toner; and New York dealer Betty Krulik, who is also engaged in catalogue projects for William Merritt Chase and Willard Metcalf. Of Hobbs, Krulik says, “Susan, like the artist she studied, went about her project quietly, diligently and with grace and elegance. Her accomplishment demonstrates a lifetime of dedication and commitment to advancing this worthy artist. This product of decades of work is one of the most beautiful catalogues raisonné published.”

“In The Garden,” circa 1894. Oil on canvas, 20-5/8 by 35 inches. Smithsonian American Art Museum, gift of John Gellatly, 1929. Turning imperceptibly like flowers on a stem, Dewing’s willowy forms echo the long-lined lilies at their feet.

Hobbs mined Dewing’s papers, some held by the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art and others still with the artist’s descendants. Her collaboration with Dewing Rooney, herself a practicing artist, proved fruitful. The two met nearly four decades ago at Kennedy Galleries in New York, bonded over a trip to Cornish three decades ago and as the project neared completion worked with a photographer to identify and reproduce archival images, many published for the first time in these volumes. “I’m just so grateful to Susan for saving endangered material and making Thomas and Maria known again,” Dewing Rooney says.

The author also visited with Connecticut artist Nelson Cooke White (1900-1989), who knew the Dewings in the 1920s. After White’s death, his son George and daughter-in-law Betsy emptied their attic for the scholar. “There were many rare catalogues, little things, from Montross, Dewing’s first major dealer in New York. They had hardly been touched,” marvels Hobbs, who hopes her papers, including these, will eventually join the Dewing trove at the Archives of American Art.

“Oh yes, it was always noised about the colony,” architect Geoffrey Platt (1905-1985), a son of Charles Adams Platt (1861-1933), designer of the Freer Gallery, told Hobbs when she inquired about Dewing’s reputation as a lady’s man. No stranger to illicit pleasure, architect Stanford White (1853-1906) touted Dewing’s paintings, some enclosed in White’s signature frames, to his clients. Along with Augustus Saint-Gaudens and several others, Dewing and White were members of a private gentleman’s retreat, the so-called Sewer Club.

On a visit to Doveridge, the former Dewing farmhouse in Cornish, Hobbs met resident con man Christian Gerhartsreiter, a.k.a. Clark Rockefeller, whose current address is San Quentin Prison. “I shudder when I look back on it,” says Hobbs, who, like the rest of the world, was at the time unaware of his true identity. More fruitful were her meetings with important Twentieth Century collectors of Dewing’s work, among them New Yorkers Margaret and Raymond Horowitz, who bought before prices began accelerating in the 1980s. The record price at auction for a Dewing canvas is $3.4 million, though privately his paintings are said to have achieved more.

Hobbs’ spade work turned up dozens of paintings, drawings and documents unknown at the time of the Brooklyn Museum retrospective. Now at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts and in a Stanford White frame, “The Lute,” a psychologically challenging oil on panel of 1903, came to the art historian’s attention when someone unexpectedly wrote to her. “It had just been sitting in someone’s basement when I found it. Now it is safe where it will be studied and appreciated,” she says. Similarly, Hobbs located Dewing’s 1895 oil “Portrait of Elizabeth Platt Jencks,” a Whistler-influenced likeness of a Cornish neighbor now at the M.H. de Young Memorial Museum in San Francisco.

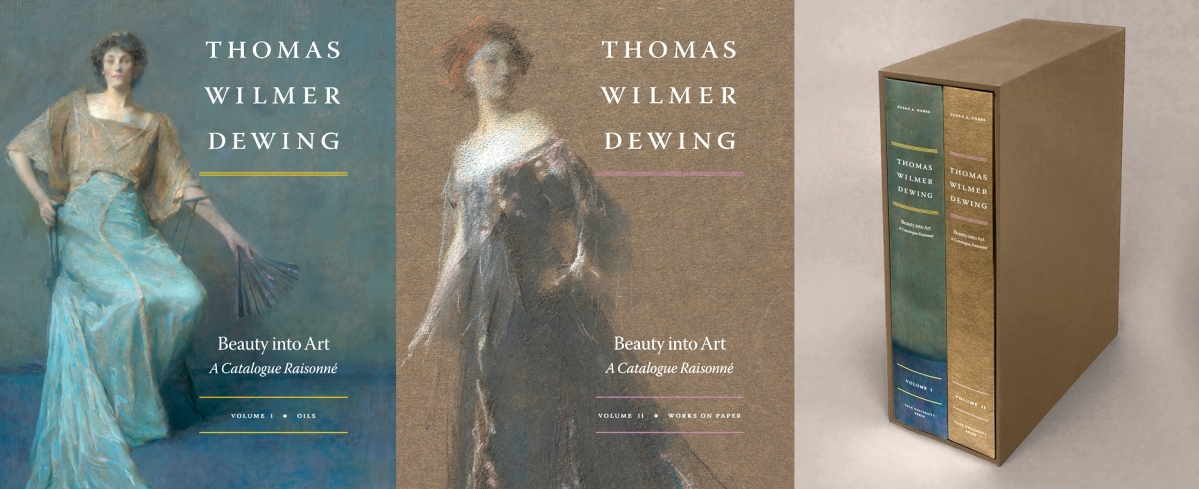

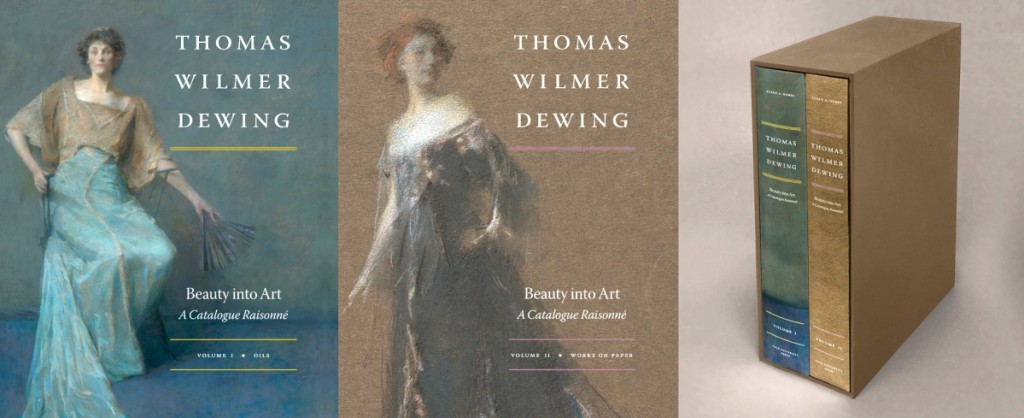

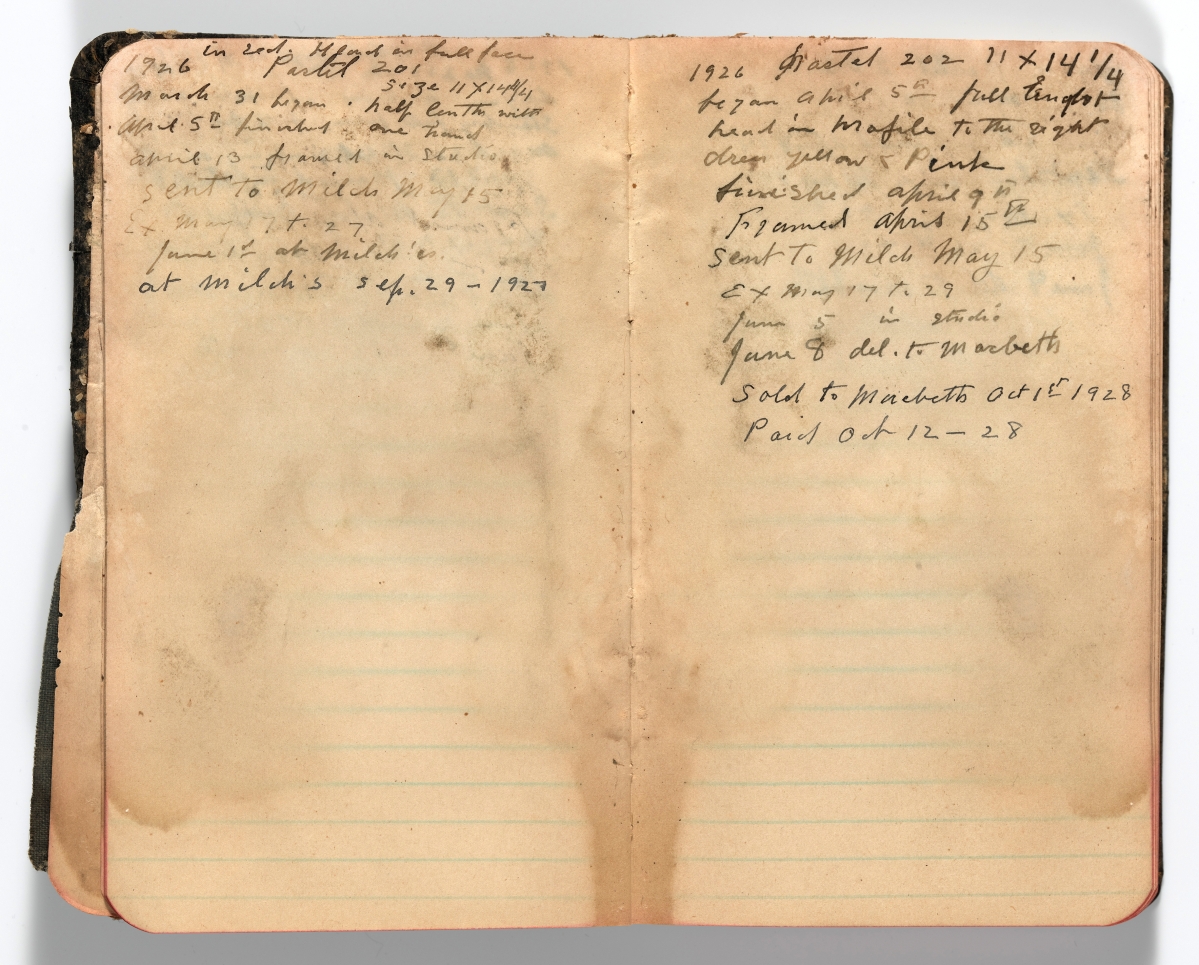

Thomas Wilmer Dewing: Beauty into Art, A Catalogue Raisonné by Susan A. Hobbs with Shoshanna Abeles is published by Yale University Press. The two hardcover volumes are enclosed in a slipcase. Volume 1 includes oil paintings and notes on frames. Hobbs’ biography of the artist begins with his early years, 1876-1880, before discussing Dewing’s Aesthetic period in the 1880s-90s. The last three chapters address portraiture, figures in landscapes and figures in interiors. Volume II explores pastels, silverpoints, lithographs and drawings by the artist. It includes both a subject index and a title index. The catalogue is available for purchase at www.thomaswilmerdewing.org.

Jonathan Boos urged Hobbs to replace old transparencies with new digital photography for every work shown, a challenge the project team strove to achieve. The resulting plates replicate Dewing’s distinctive color harmonies, particularly his inscrutable greens, as well as the gauzy texture of his drawings with impressive fidelity. The publication went through five color corrections, four in Seattle at the offices of book producer Lucia/Marquand and the last in China, where the volumes were printed. “You need more than one pair of eyes,” says Hobbs, who was joined at Artron in Shenzhen by Abeles and the book’s designer, Ryan Polich. There to work on a publication of Rembrandt etchings, Polich’s colleague, designer Tom Eykemans, pitched in. “The Chinese technicians were not happy when Ryan left. Tom, who communicated by hand gestures – he put his fingers together in a little point and pushed up or down for more or less cyan or magenta – was essential,” Hobbs recalls.

In June, some of Hobbs’ dealer friends hosted a cocktail party for her at Menconi + Schoelkopf’s East 80th Street gallery in New York City. Aside from such appearances, the scholar, her work complete, says she has no plans for a follow-up book, either a popular treatment of the infinitely interesting Cornish colony or an expanded treatment on the work of Maria Oakey Dewing, chronicled by Hobbs in the January 2004 issue of The Magazine Antiques.

“Really, at the end what you want is a picture of the artist as a real person struggling to make a mark at a particular point in American culture. The individual works are interesting to those who own them, but here what is essential is the overall accomplishment of an important artist who had been swept aside after the 1913 Armory Show brought in abstract and Modernist sensibilities,” she says.

Few of us could summon the discipline needed to pull off a project of this scale, let alone achieve such impeccable results. Dewing Rooney, who infuses brilliant color into floral studies and landscapes as mysterious as those of her forebears, says her friend tempers tenacity with courtesy. Hobbs’ self-knowledge, something she may have in common with her subject, was essential. As Hobbs explains, “Finishing something that is hard to do validates the fact that it was the right thing to do. There are failed books, books I thought I’d write. Now when I look back, I realize it was for someone else to write them. And that’s alright.”

Thomas Wilmer Dewing: Beauty into Art, A Catalogue Raisonné by Susan A. Hobbs with Shoshanna Abeles. Yale University Press, 2018, pp. 1,056, 637 color illustrations, hardcover with slipcase, $300. To purchase, go to www.thomaswilmerdewing.org or https://yalebooks.yale.edu or call 203-432-0960.

.jpg)