“To me the simple act of tying a knot is an adventure in unlimited space … limited only by the scope of our own imagery and the length of the ropemaker’s coil.” —Clifford W. Ashley, The Ashley Book of Knots

By W.A. Demers

NEW BEDFORD, MASS. – “When you reach the end of your rope, tie a knot in it and hang on.” The spurious proverb attributed to Thomas Jefferson actually stems from the American West, where it appeared in a 1946 folklore book. The quote, however, is a nice conceit upon which to hang an exploration of the ubiquitous, sculptural and mathematically elegant entities that both complicate and simplify our lives. And that is just what the New Bedford Whaling Museum (NBWM) has done with “Thou Shalt Knot: Clifford W. Ashley,” an exhibition running through June 2018 that explores the work of master knot-tyer, maritime artist, historian and author Clifford W. Ashley (1881-1947).

Ashley’s daughters, Phoebe Chardon and Jane Ashley, donated their father’s private knot collection to the museum in 2016, and these gifts are augmented by the museum’s own interpretative material as well as Ashley’s paintings and prints, and works by other knot-tyers and artists.

Knots tie together both ancient and modern, as this exhibition reveals – the continuous thread running from antiquity to the modern-day fields of mathematics, physics, life sciences, materials engineering and art. A focal point of the exhibition is The Ashley Book of Knots, and the collection includes many of the knots Ashley used as models for the almost 7,000 illustrations in his encyclopedic magnum opus. His book has been in continuous print since 1944, translated into several foreign languages and used as a springboard by many other authors examining the subject.

To better understand Ashley’s sinuous subject, it helps to know a bit about “Grandfather Ashley,” as his grandchildren affectionately call him. According to grandson Marc Chardon, Ashley came from a time “when entertainment was something people created, rather than watched.”

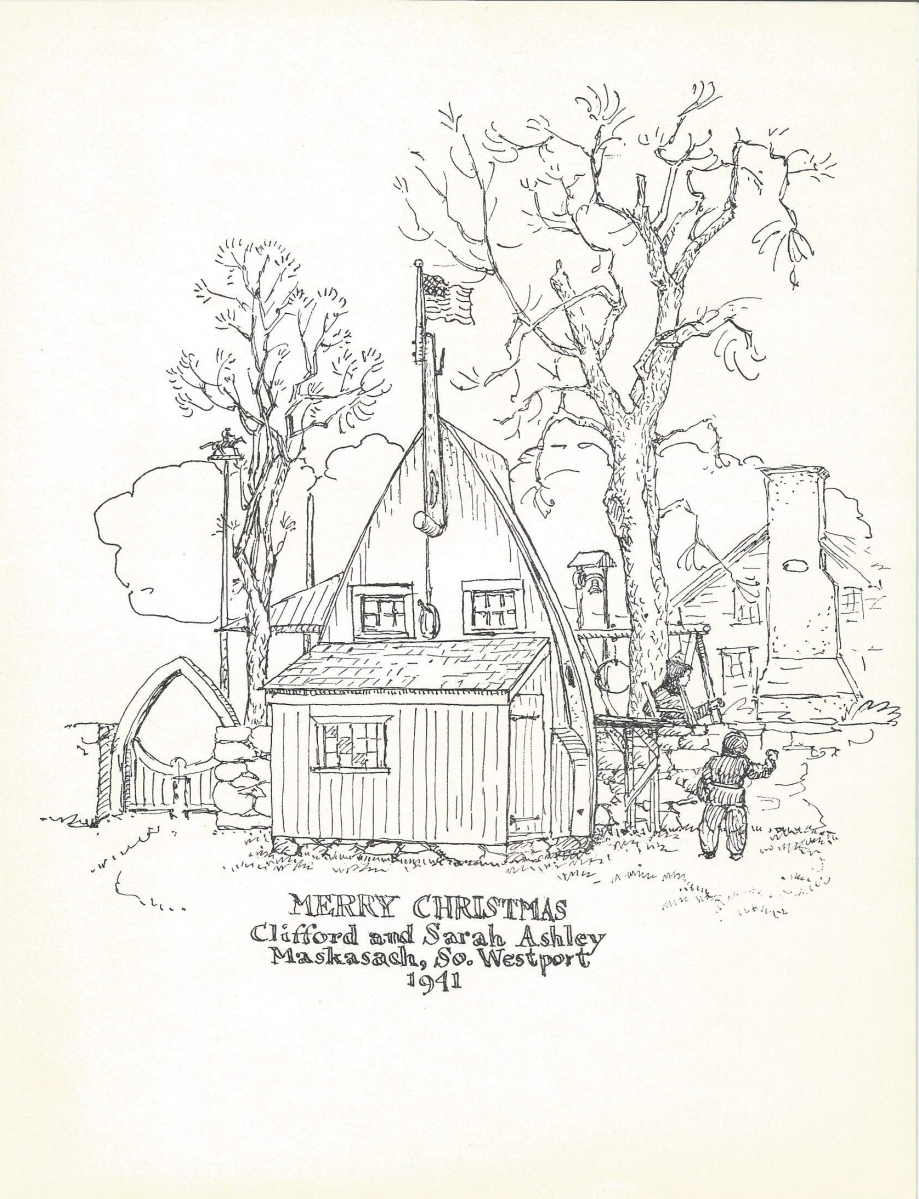

Married relatively late in life, age 50 when he tied the knot with Sarah Delano, Ashley immediately took on 3-year-old daughter Pauline from Sarah’s previous marriage and in the space of about four years fathered two more girls, Phoebe and Jane. Jane in the exhibition catalog’s preface recalls that her father was an old-fashioned gentleman, strict but fair. “Our punishment for bad behavior was a spanking, at that time still considered acceptable, and I can attest to its efficacy,” she writes.

Married relatively late in life, age 50 when he tied the knot with Sarah Delano, Ashley immediately took on 3-year-old daughter Pauline from Sarah’s previous marriage and in the space of about four years fathered two more girls, Phoebe and Jane. Jane in the exhibition catalog’s preface recalls that her father was an old-fashioned gentleman, strict but fair. “Our punishment for bad behavior was a spanking, at that time still considered acceptable, and I can attest to its efficacy,” she writes.

Ashley donned the typical business attire of suit, bow tie and fedora before heading off to his studio near the harbor in Fairhaven, and while he did all the dutiful chores of work and family, he still found time and energy to entertain – both at social gatherings conducted at home and with a series of rope swings, climbing ropes – with knots, of course, to facilitate small climbers – and an elaborate maze of arbor vitae marked with string from tree to tree. “The prize for successful navigation to the center of the maze for his many friends was a table stocked with an ample supply of dry martinis,” recalls daughter Jane.

An old fishing boat, no longer seaworthy, was cut in half and repurposed as a whimsical structure for storing yard tools and children’s playhouse.

Maskasach, the Ashley family’s home in Westport, Mass., was a sprawling saltwater farm comprising the original farmhouse, which Ashley improved and expanded, his studio, a guest house, barns, sheds and even a tennis court. Equally knowledgeable about American antiques as he was about art, he filled it with examples of scrimshaw, glass, country furniture, prints, paintings, ship models, treen, Chinese export porcelain and more, his collection informed by his eye for form, line and color. After his marriage to Sarah in 1932, Maskasach also became the inspiration for the family’s annual Christmas cards, for which Ashley would create homey pen and ink illustrations of its buildings and grounds.

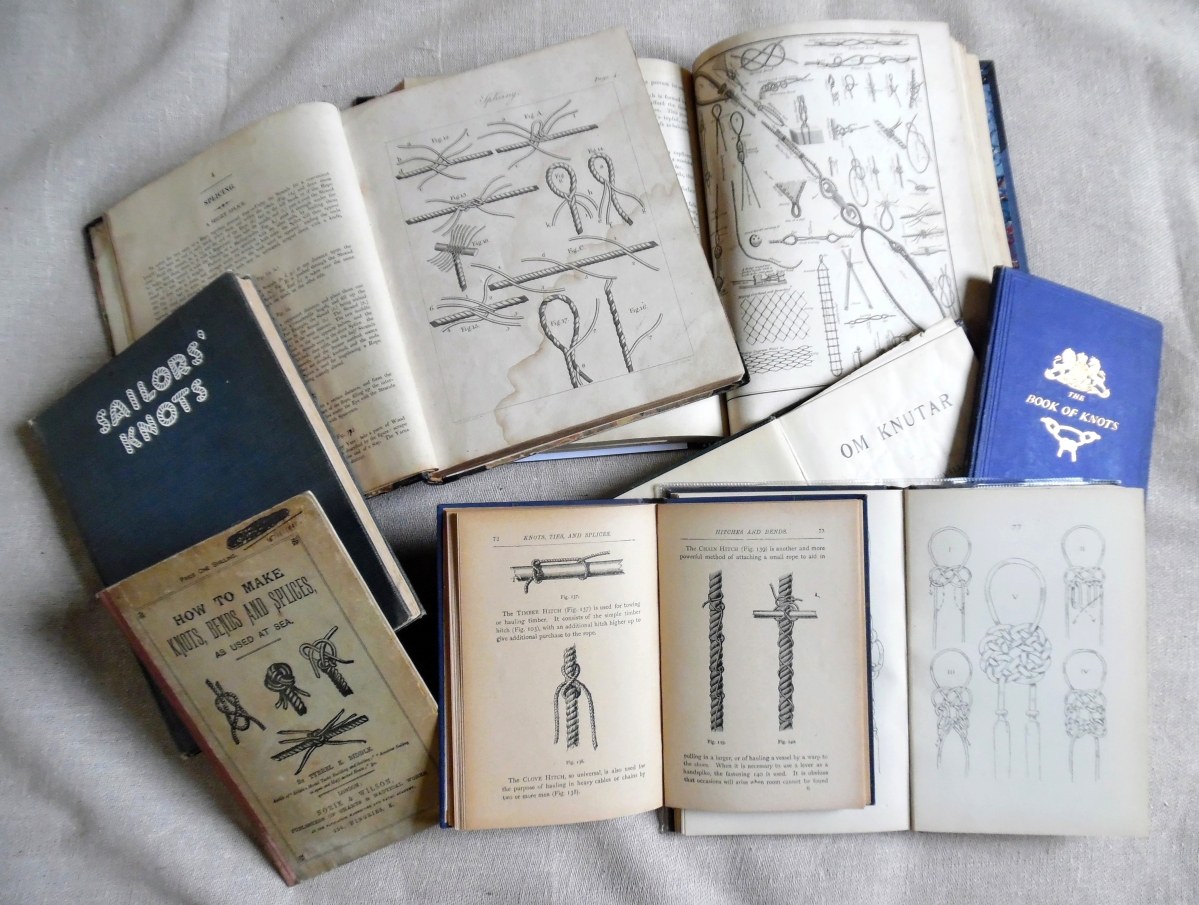

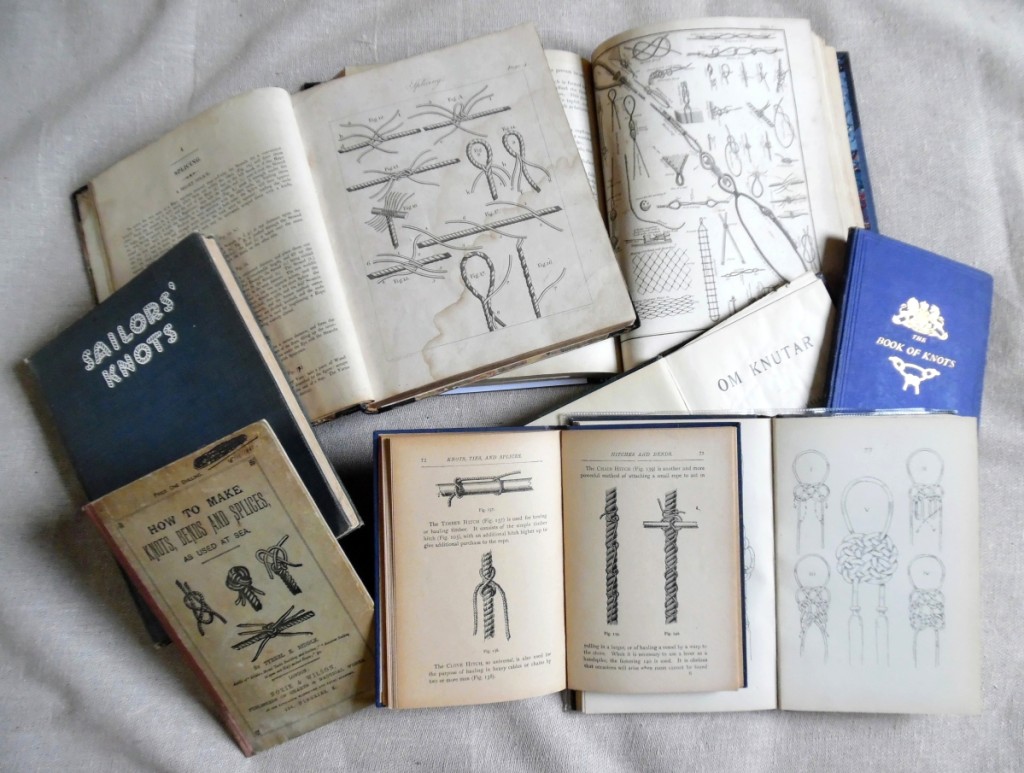

A selection of works on knots that Ashley consulted. Ashley’s own The Book of Knots was translated into German, Spanish, French and Italian editions.

The more serious side of Ashley was evident in his art, an interest that was awakened in high school, further nurtured at the Eric Pape Art School in Boston and blossomed with later friendships with N.C. Wyeth and studies with Howard Pyle. Ashley developed a talent for magazine illustration, mainly as a way to defray tuition expenses, and one such commission, for Harper’s Monthly magazine, put him aboard a whaling ship, an experience that is said to have informed much of his later work. After 1913, however, much of his output was formal painting on canvas. One of these paintings, an oil on canvas of a Southern landscape with live oaks and Spanish moss, was among the top lots at a Pook & Pook auction this past July.

A contiguous exhibition, in fact, features Ashley’s works on canvas and book illustrations. He published one of his most important books, The Yankee Whaler, in 1926 on the whaling industry; the elegantly illustrated Whaleships of New Bedford was published in 1929 with a foreword by Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

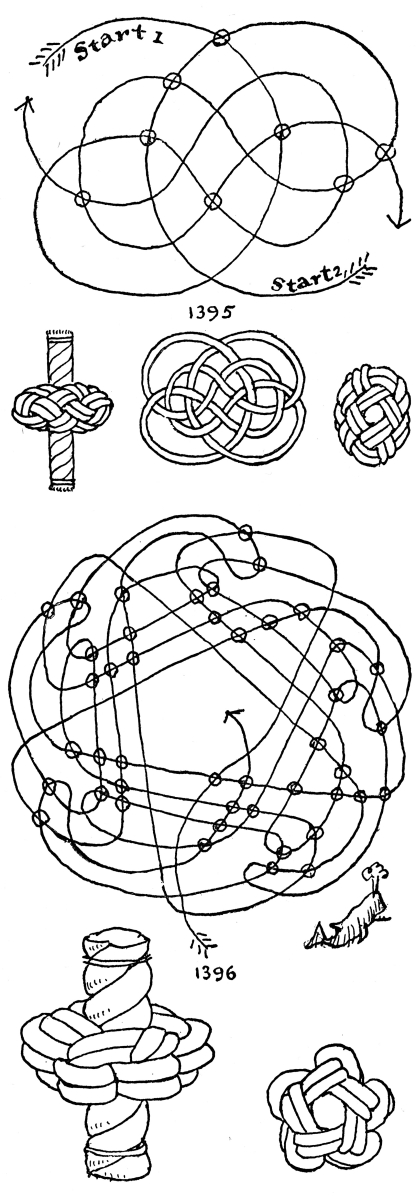

He published The Ashley Book of Knots in 1944, and it is, of course, the collection of knots that forms the focal point for the NBWM exhibition. Even an Eagle Boy Scout would go slack-jawed at the variety – Turk’s Head and Monkey’s Fist knots, sailor’s knot-tying tools, Victorian braided mourning hair wreaths and jewelry, military brocades and an array of paintings, prints and original book illustrations on the subject.

And just as it always helps to have dad show junior how to make that Windsor knot in a necktie, there are videos of knot-tying, ropemaking and interactive displays explaining the mathematics of knots, while ropemaking machines and other tools are on hand for visitors to see. The exhibition also includes modern works in various media that speak to a contemporary understanding and meaning of knots, including macro views of rope in large graphite works on paper and static ceramic sculptures of rope and sailcloth.

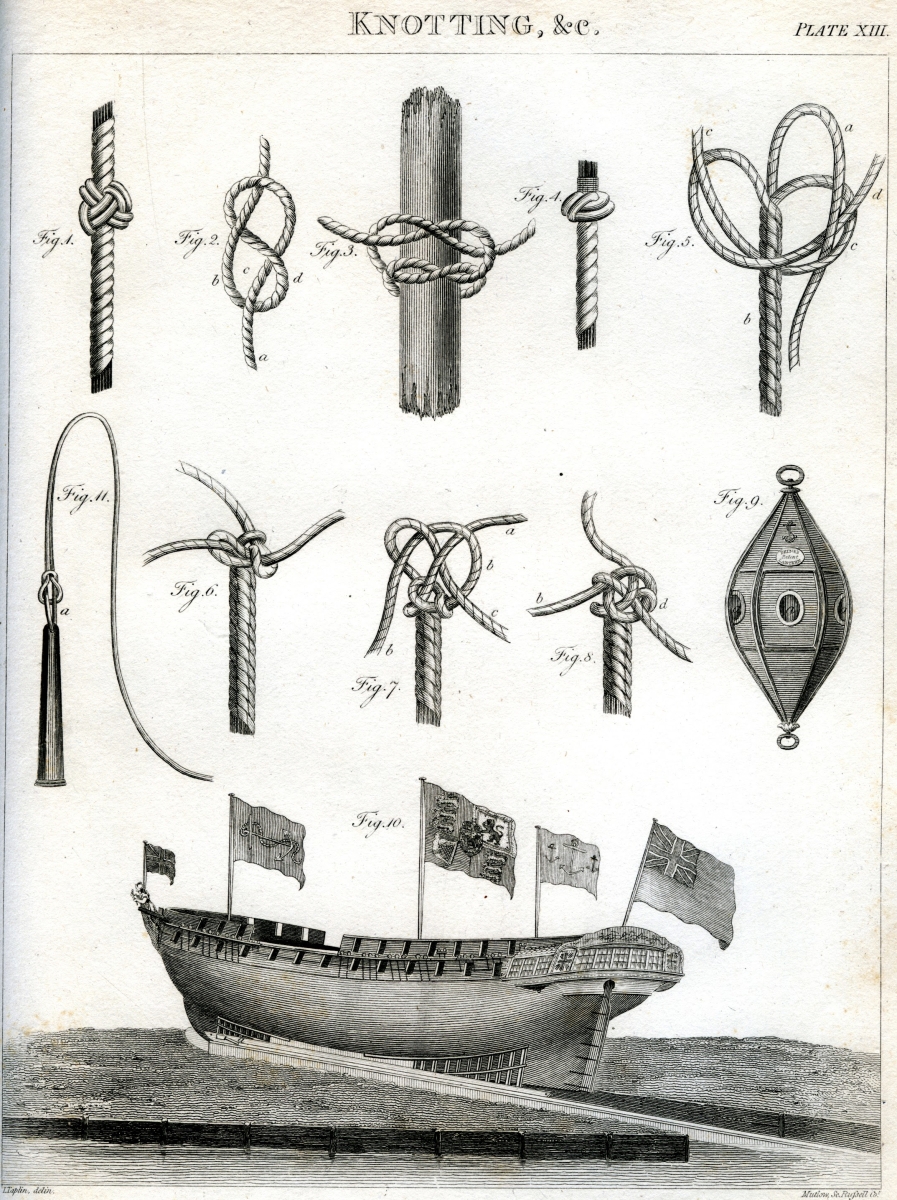

Being shown how a knot is tied, after thousands of years, is still the best way to appreciate the art. Ashley understood this and drew from seamen’s dictionaries and manuals to name and illustrate certain knots. In English, Seaman’s Dictionary by Sir Henry Mainwaring was one of the earliest, first circulated in manuscript form about 1620-23 and published posthumously in 1644. It mentioned the sheepshank knot, most commonly used to shorten a rope. It was not until 1866 in London that the first specific knot book in English was published. The Book of Knots by Tom Bowling presented three foldout plates showing about 150 knots, ties and splices.

Ashley synthesized this and more over a grueling 11-year period, and when his The Ashley Book of Knots was published in 1944, it quickly became regarded as the pinnacle of books on knots and knotwork, a veritable “knot-tyers bible,” if you will, cataloging some 3,900 knots, illustrated with 7,000 drawings and informational graphics. Nearly three-quarters of a century later, Ashley’s book remains the most comprehensive repository of knot knowledge. Technological developments over that span of time, of course, have made improvements in the black and white illustrations and photographs that dominated the early publications. The advent of lower-cost color printing, computer-generated color illustrations, DVDs and now YouTube video tutorials bolster the return of show-and-tell teaching.

Said Des Pawson, the exhibition catalog’s essayist on the history of knot tying, however, “books remain an important tool and The Ashley Book of Knots continues to be the definitive work, the place to go for information on the origins of knots and how to tie them, and, I believe, it will continue to be so for a very long time.”

Ashley’s book even proved inspirational to novelist Annie Proulx, who said of her Pulitzer Prize winning novel The Shipping News, “Without the inspiration of Clifford W. Ashley’s The Ashley Book of Knots, which I had the good fortune to find at a yard sale for a quarter, this book would have just remained a thread of an idea.”

Complementing the Ashley collection in the exhibition are a broad range of objects and rare books drawn from the Whaling Museum’s permanent collection, partner institutions and private collections that help to place Ashley’s work within a larger cultural, social, industrial, artistic, and utilitarian context. A full color, 84-page catalog accompanies the exhibition.

As esoteric as the subject of knot-tying may seem, this exhibition resonates with popular collections seen up and down coastal regions in the United States, such as Mystic Knotwork, a workshop in Mystic, Conn., run by Matt Beaudoin, whose grandfather opened the family knot shop in 1957. Here, overlooking the Mystic River, one can see handmade knots being created, see museum-quality works that make up a part of the family’s history and purchase everything from ready-made sailor bracelets and nautical accessories and décor to the rope and cord for one’s own DIY crafting – as long as you have Clifford Ashley’s book handy for reference or you may come undone.

The New Bedford Whaling Museum exhibition is sponsored by the family of Clifford W. Ashley and made possible, in part, by support from the International Guild of Knot Tyers, the Boston Marine Society, Margaret Baker Howland and Mary Howland Smoyer. It is curated by Christina Connett, PhD, the museum’s chief curator.

The New Bedford Whaling Museum is at 18 Johnny Cake Hill. For information, www.whalingmuseum.org or 508-997-0046.

.jpg)