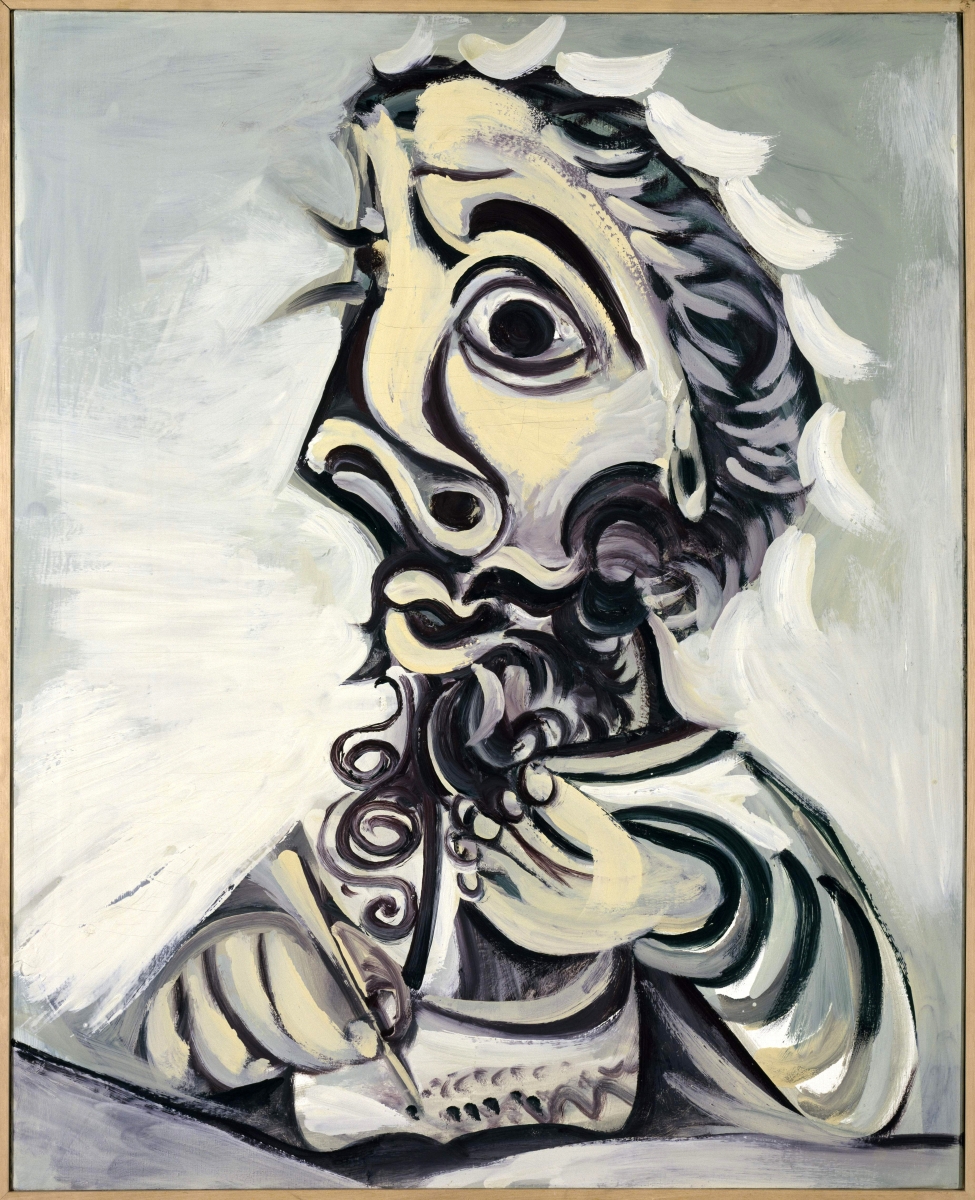

“Head of a Bearded Man” by Pablo Picasso, 1938. Oil on canvas, 21 by 18 inches. Musée Picasso Paris. © 2017 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo Jean-Gilles Berizzi.

By James D. Balestrieri

KANSAS CITY, MO. – Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) must have seen the forms of faces everywhere he looked, faces looking back at him, faces he suspected were masks that he wanted to strip off through his art. What he sought in those faces, and in the manifold works that were the products of his seeing, was something irreducible. God – an irreducible abstraction – was somewhere underneath these faces. What he needed was a way to pierce the surfaces, to excavate the true visage and likeness of the universe, a universe he saw not as nature, but a higher order of art. To get at the face, he painted the mask. To get at the sacred, he sculpted the embodied spirit of the sacred. This is the paradox that the arts of Africa, Oceania and the Americas taught him. To see the faces that were staring back at him from everywhere he had to see them not as faces but as masks, and to see the sacred, he had to see how others saw and rendered the sacred in their art.

The epiphany that sent Picasso on his journey toward becoming the Picasso we know – or think we know – came on a single day in June 1907, when the artist wandered into the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro in Paris. In 1939, he described the moment to Andre Malraux: “When I went to the Trocadéro, it was disgusting. A flea market. The stench. I was all alone. I wanted to get out. I didn’t leave. I stayed. I stayed. I understood it was really important: surely something was happening to me… I understood why I was a painter. All alone in this dreadful museum, with masks, redskin dolls, dusty manikins. ‘Les Demoiselles d’Avignon’ may well have happened that day, but not at all due to the forms, but because it was my first ‘exorcism’ canvas – that, yes!” And then, “I wanted to get out fast, but I stayed and studied. Men had made those masks and other objects for a sacred purpose, a magic purpose.”

On view in Kansas City through April 8, “Through the Eyes of Picasso” was organized by Yves Le Fur of Musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac in partnership with Musée national Picasso-Paris, and adapted for the United States by Julián Zugazagoitia, Menefee D. and Mary Louise Blackwell CEO and director of the Nelson-Atkins. The exhibition weaves the revelation of the “primitive” arts of non-Western cultures through Picasso’s long career, offering direct comparisons between masks, statues and objects he collected and admired, and artworks he created.

Since its opening in Kansas City in October 2017, nearly 50,000 visitors have viewed the presentation featuring roughly 170 works of art, including more than 60 paintings, sculptures and ceramics by Picasso alongside more than 20 works of African and Oceanic art that were part of his personal collection. Accompanied by an illustrated catalog produced by Musée du quai Branly, “Through the Eyes of Picasso” was named one of the best exhibitions of 2017 by the Wall Street Journal.

The exhibition argues that something more visceral than imitation, more “primitive” in a Freudian sense, was at work in Picasso’s creative process. Scholar Marie-Laure Bernadac, in a 2008 essay quoted extensively in the catalog, diagnoses Picasso as having had “acute pictorial cannibalism,” where cannibalism is anthropological, meaning the ingestion of the Other – the antagonist (enemy?), as a gesture of respect, and even of love, intended to assimilate and metabolize the Other’s power. By 1907, the exhibition argues, Picasso was no longer satisfied with Western fare. Mimesis, the artistic representation of “reality,” which at its best revealed the inner lives of figures and the underlying truth of nature, no longer sated his appetite. Picasso was ready for the Trocadéro.

The exhibition argues that something more visceral than imitation, more “primitive” in a Freudian sense, was at work in Picasso’s creative process. Scholar Marie-Laure Bernadac, in a 2008 essay quoted extensively in the catalog, diagnoses Picasso as having had “acute pictorial cannibalism,” where cannibalism is anthropological, meaning the ingestion of the Other – the antagonist (enemy?), as a gesture of respect, and even of love, intended to assimilate and metabolize the Other’s power. By 1907, the exhibition argues, Picasso was no longer satisfied with Western fare. Mimesis, the artistic representation of “reality,” which at its best revealed the inner lives of figures and the underlying truth of nature, no longer sated his appetite. Picasso was ready for the Trocadéro.

The artworks in “Through the Eyes of Picasso” are organized by motifs – though perhaps modes or tropes would work as well – that are physiological and psychological, spatial and spiritual. It is important to note that these categories are fluid, and that works can belong or move between several at once.

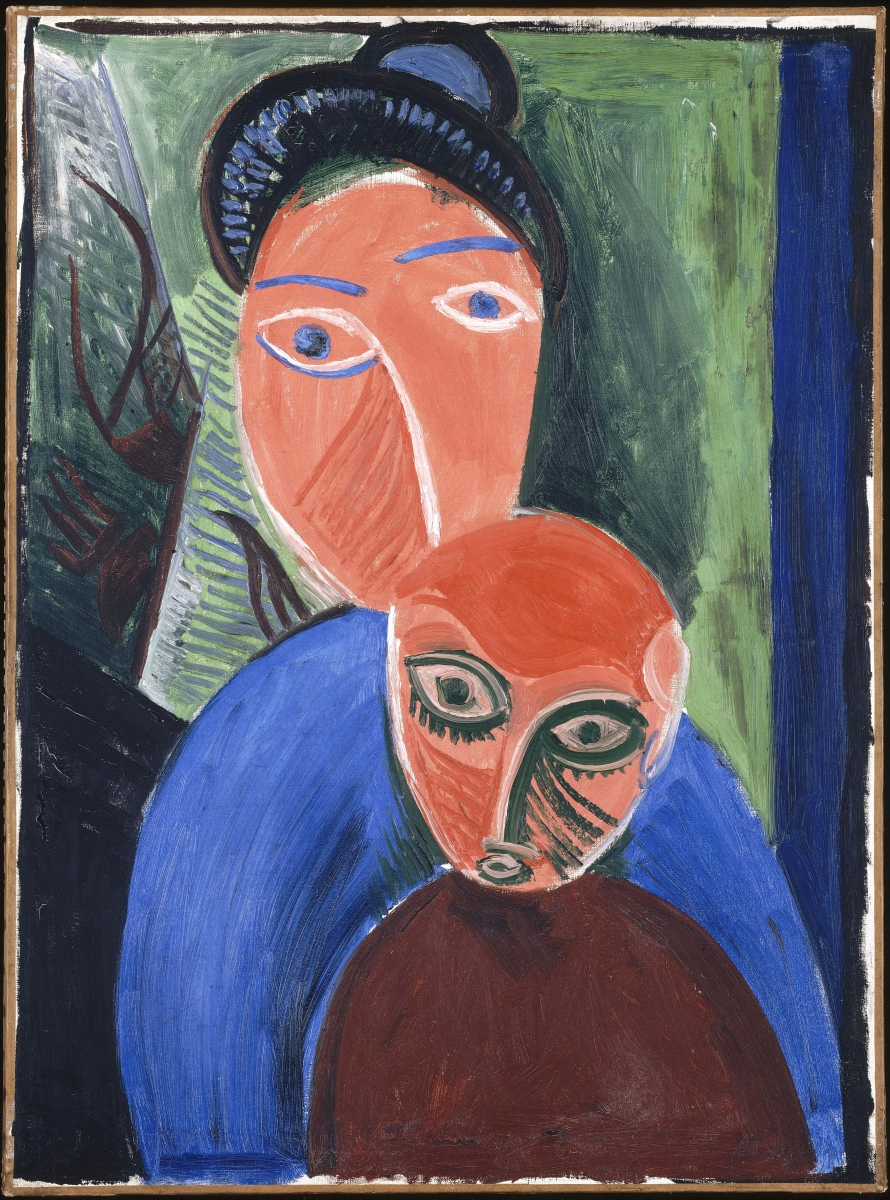

One of the most important motifs is “The Gaze,” and a comparison between the Gunye ge anthropomorphic mask from the Dan people in Côte d’Ivoire and Picasso’s 1907 “Male Bust (Study for Les Demoiselles D’Avignon).” They testify to the artist’s interest in reducing the face to its neutral, abstract essence, all but devoid of individual characteristics. Holes for eyes, a few lines to delineate features, a mouth betraying emotion, but without any discernibly definable emotion. Picasso saw such faces staring back at him at the Trocadéro and felt their profound, magical influence in his own artistic practice.

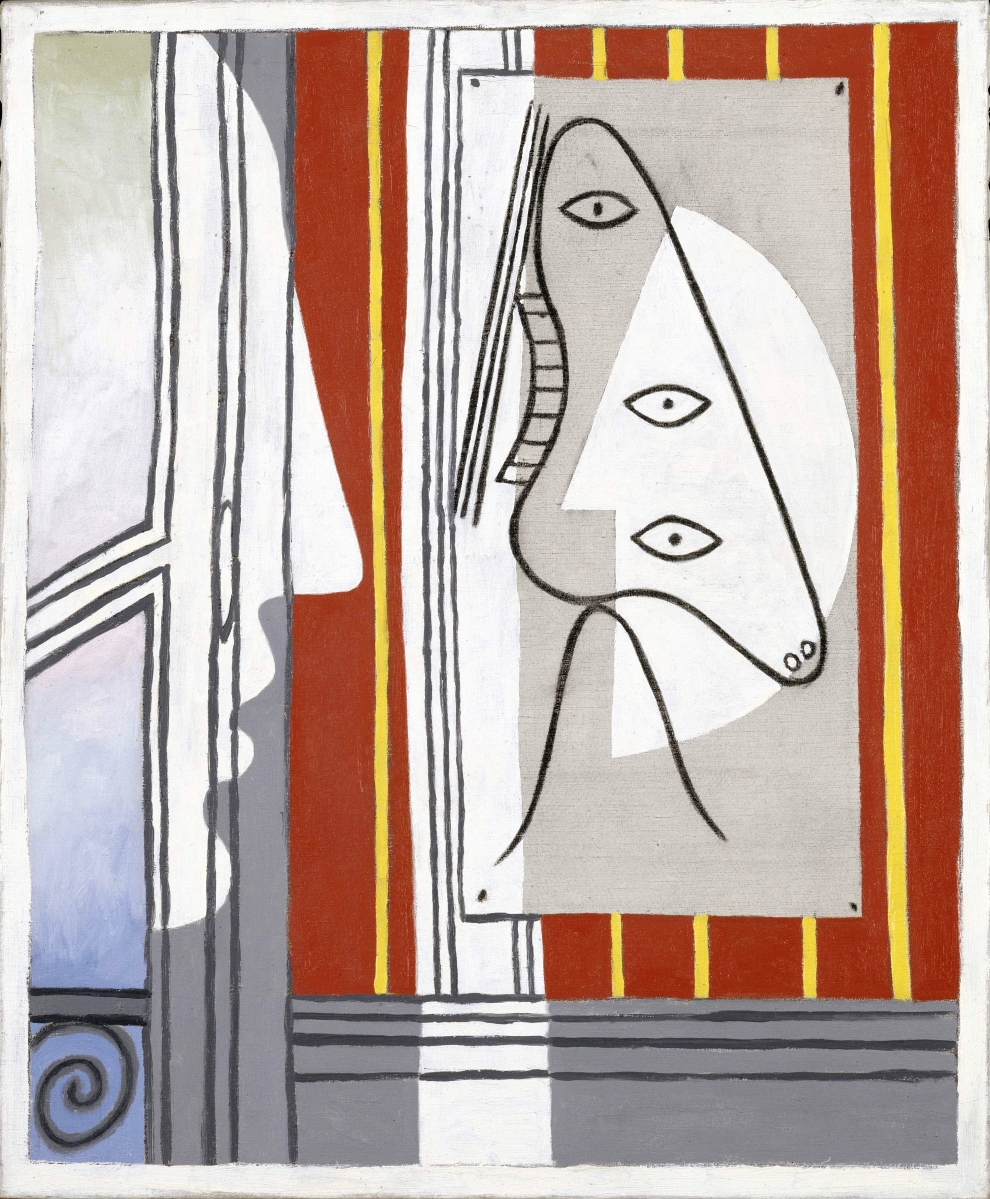

“Verticality” defines the human in simple spatial terms. Standing erect, perpendicular to the illusory horizon and the true curve of the Earth, perpendicular to the grave, reveals itself as an almost heroic act of evolution. Menedjai kul currency from Chad and Picasso’s 1928 oil “Figure and Profile” reflect this geometry. While the Chadian currency has the physics-defying quality of a standing, elongated shadow, Picasso’s painting offers an entangled duality in which the profile emerges as a kind of sinuous figure while the figure becomes an abstracted profile.

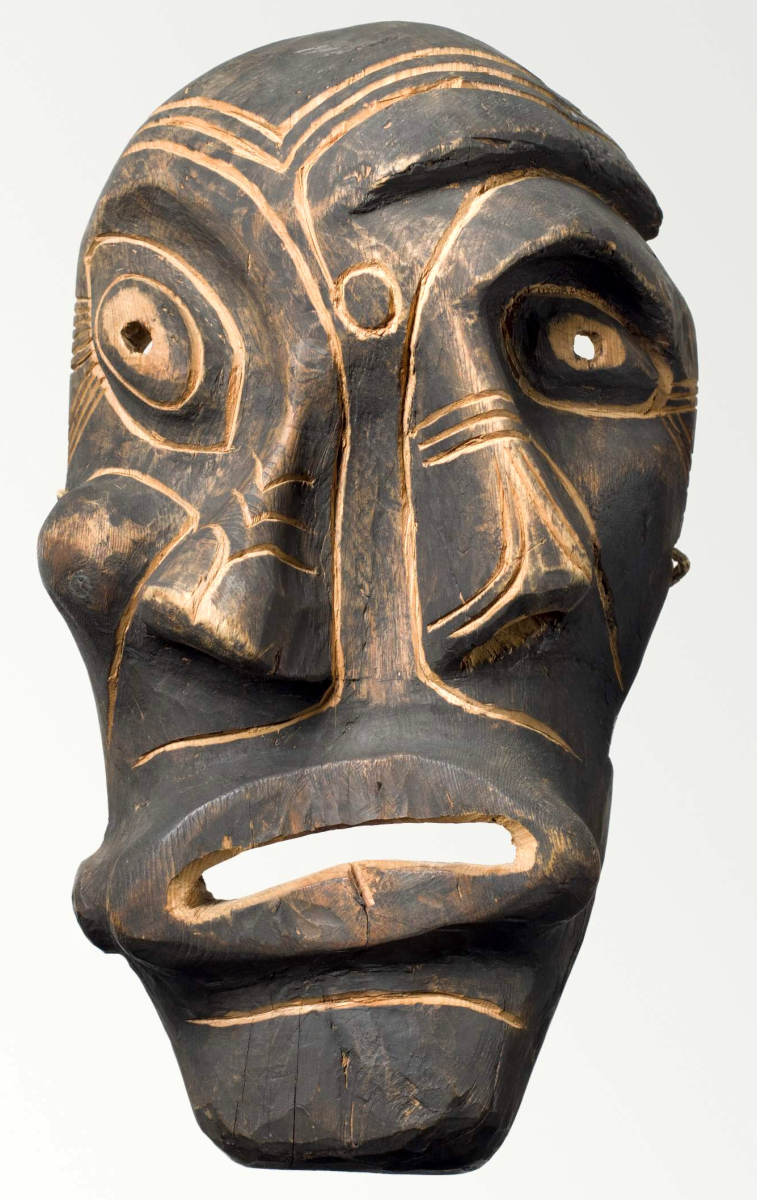

The intertwined morphologies in “Figure and Profile” take metamorphic shape in an “Animal-Human/Human-Animal” trope in a pair of works: the Otomi Mask from Mexico and a 1938 canvas “Head of a Bearded Man.” The fusion of human and animal hark back to the earliest rituals. Mythological hybrids such as the Minotaur (a creature that would come to obsess Picasso) remind us of our animal natures and the thin veneer of humanity that separates us from them. Both the Otomi Mask and “Head of a Bearded Man” suggest the satyr, a trickster character that lives on the outskirts of the human world, between waking reality and the dream.

Images are even more interwoven in the “Mise en Abyme” trope, where smaller copies of images are set within themselves. Think of the infinite regressions of facing mirrors and you get the idea. In contemporary math and physics, the mise en abyme is fractal – the smallest parts of snowflakes or crystalline structures, or cells, replicating the shape of the whole. Picasso’s “Large Still Life with Pedestal Table” and the Malanggan ceremonial carving from Papua New Guinea exhibit repeated feathery forms, eyes and curving arabesques as if the larger ones have spawned the smaller. These are purely generative creations in which anything can give birth to or become anything else, simply by virtue of congruences in form. The masks here, once stripped away, reveal only other masks. These are artworks as onions – layered, lacking centers, needing none.

Mask, Piedra Ancha, Mexico, Otomi culture, 1900s. Wood, fur, horns, 15 by 10 by 8½ inches. Musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac, Paris. —Claude Germain photo

In 1920, when asked his opinions on “African Negro art,” he replied, “African Negro art? Don’t know it.” Scholars have been parsing the meaning of this seemingly flippant response for decades. Perhaps dwelling on the ethnographic, anthropological aspects of African art – and, by extension, all non-Western art, which did not interest him – would have somehow diminished those works as living art, nailing them to specific countries, cultures and belief practices. Picasso famously despised exoticism, that is, the juvenile notion that non-Western arts were attractive because they were “colorful” and “different,” so when he said he knew nothing of the arts of Africa, he may well have meant that the non-Western artworks he saw and collected, works that had so profound an influence on him, were, quite simply, works of art made by fellow artists. They were all art, without culture or nation. To Picasso, art was its own reality, running beside, beneath and above ordinary reality. Artists, whoever they were, and artworks, wherever their gaze met his, were similarly beside, beneath and above. “Artist” was the highest compliment Picasso could pay, far higher than “African Negro artist.”

This asks a very contemporary question: must artists be anthropologists? What do artists owe to their sources of inspiration? When does cultural sensitivity matter and when does it cripple the artist’s iconoclastic, cannibal impulse to devour everything and make art of it? After all, Picasso was a shameless appropriator who was unapologetic about his appropriations, but he was also a transformer – of Modernism, of art, of modernity itself, of how we see art, but also of how we see and are seen.

The aesthetics of transformation might begin as appropriation, but for Picasso to become Picasso there had to be a kind of transubstantiation that day in the Trocadéro and in the act of painting the myriad forms – all of them masks of one sort or another – that followed. Expecting God when he peered beneath the masks, Picasso found a mystery instead: eyes staring back at him – eyes that were his own, and not his own. Their gaze induced him to create, to push out in myriad directions, to become Picasso.

The exhibition opened at the Musée du Quai Branly in Paris in July 2017. Following its close in Kansas City, it travels to the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, where it has been renamed “Face to Face: From Yesterday to Today, Non-Western Art and Picasso.” It may be seen in Montreal between May 12 and September 16.

The Nelson-Atkins is at 4525 Oak Street. For information, 816-751-1278 or www.nelson-atkins.org.

Playwright, author and critic James D. Balestrieri is director of J.N. Bartfield Galleries in New York City.