;.jpg)

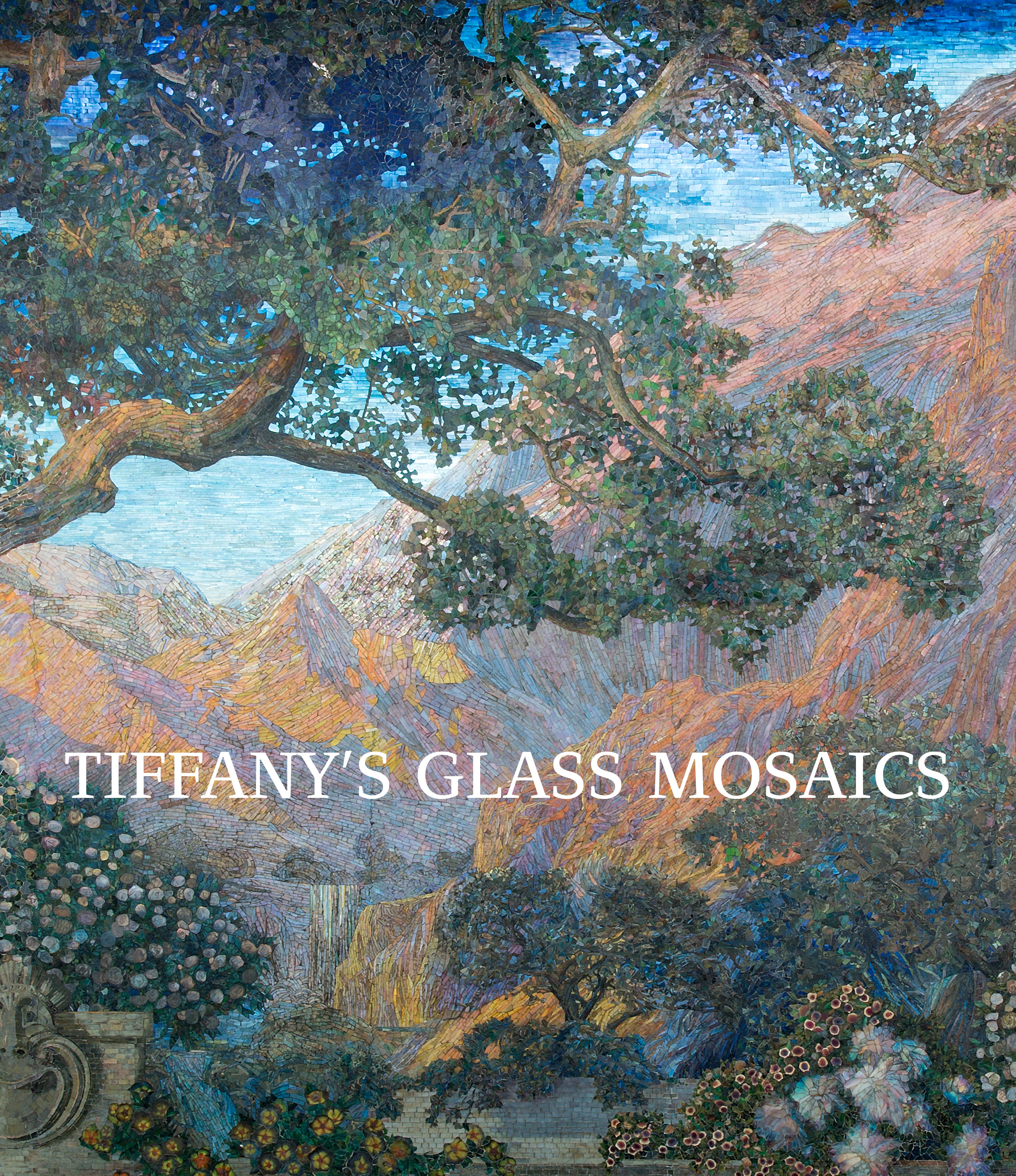

Based on a painting by Maxfield Parrish, the mural is composed of more than a million pieces of glass. It took Tiffany workers a year and a half to produce the glass and a year to create the mural. It is represented in the exhibition via a media presentation in the Mosaic Theater. “The Dream Garden” mural by Tiffany Studios, 1916, for Curtis Publishing Company Building (now Curtis Center & Dream Garden). Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.

By Kate Eagen Johnson

CORNING, N.Y. – “These pieces are painterly compositions involving glassmakers, chemists, designers, glass selectors and cutters. The visitor needs to understand the process in order to understand the finished product,” stated Kelly A. Conway, curator of American glass at the Corning Museum of Glass (CMoG), underscoring the ideas driving “Tiffany’s Glass Mosaics,” on view at the museum until January 7.

Lindsy R. Parrott, director and curator of The Neustadt Collection of Tiffany Glass, co-organized the exhibition with Conway. Speaking of the strong emphasis she and Conway placed on materials, technology and technique in both the exhibition, the first major presentation on the subject, and the accompanying publication, for which they served as co-editors and essay contributors, Parrott called it “a very different approach to interpreting Tiffany glass.”

Until now, mosaics have failed to receive the acclaim awarded to other Tiffany creations. Parrott commented, “We wanted to highlight Tiffany’s work in mosaics, which has been understudied. We wanted to explore what it looked like, the time period, and how it was new and exciting and equally innovative to the stained glass. We wanted to understand the range of production from a desk set encrusted with inlay to installations in churches, libraries and homes. The Neustadt and the Corning Museum are uniquely positioned to look at mosaics through the lens of materials and the creative process. The partnership was a fabulous fit.”

While both organizations are devoted to the medium of glass, their institutional profiles could not be more different. The Neustadt Collection of Tiffany Glass was established by orthodontist and early Tiffany collector Dr Egon Neustadt (1898-1984) as a foundation in 1969. This gemlike special collection with its razor-sharp focus gives the public access to its holdings via a dedicated gallery at the Queens (N.Y.) Museum and through loans to other museums.

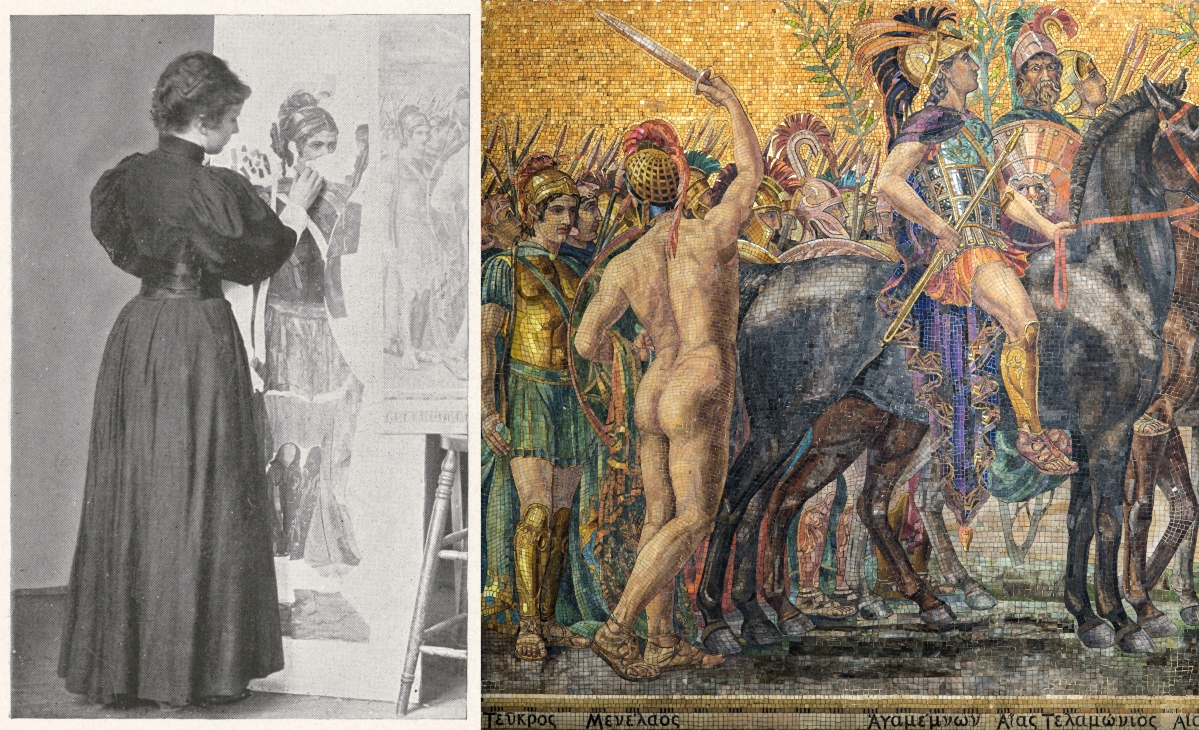

Right, detail of the mosaic frieze “Heroes and Heroines of the Homeric Story” by Tiffany Glass and Decorating Company, designed by Jacob Adolphus Holzer (1858–1938), 1896–97. Alexander Hall, Princeton University. Left, “Mosaicist Selecting Glass,” detail from Heroes and Heroines of the Homeric Story from Tiffany Glass Mosaics for Walls, Ceilings, Inlays, and Other Ornamental Work; Unrestricted in Color, Impervious to Moisture, and Absolutely Permanent (New York, Tiffany Glass and Decorating Company, 1896).

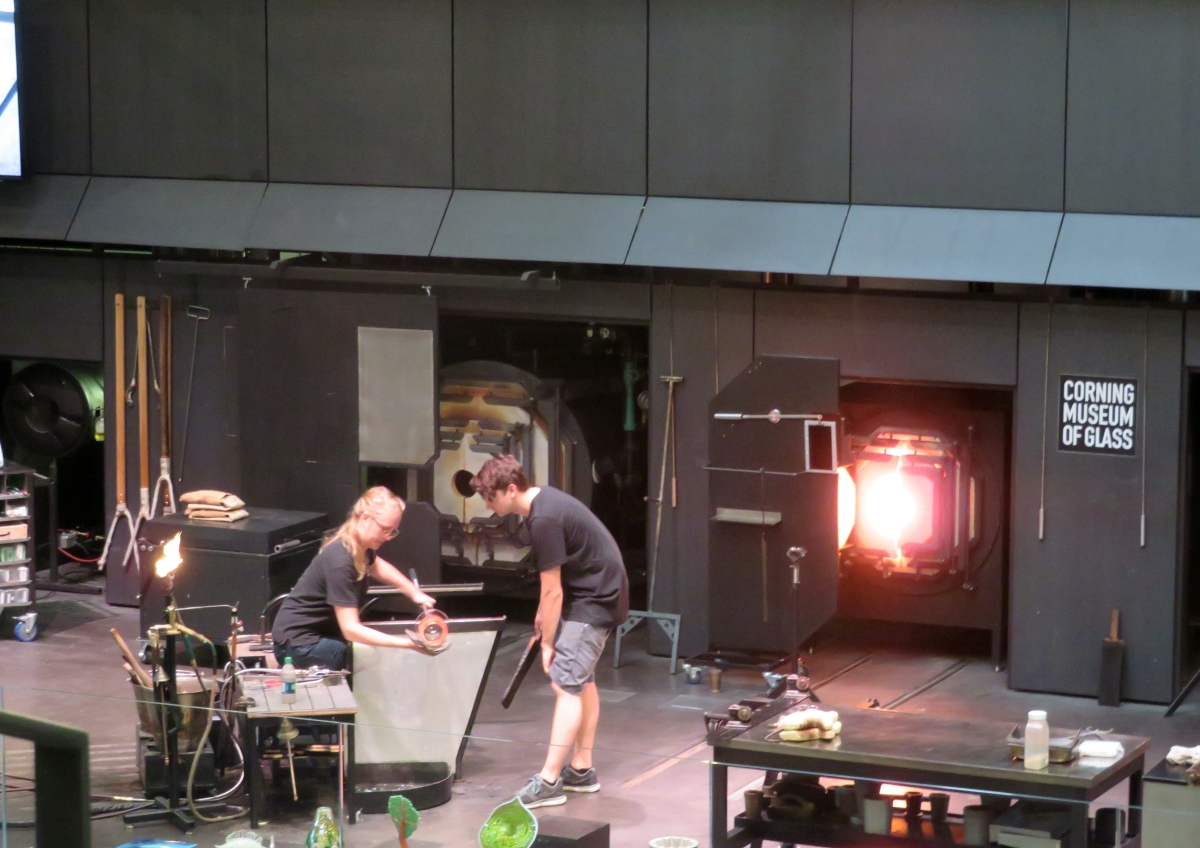

The Corning Museum of Glass, founded by Corning Glass Works (now Corning Incorporated) in 1951 as a gift to the nation, holds an encyclopedic collection of glass through time. It addresses artistic, scientific, domestic and other applications. Recent initiatives include the 2015 opening of a 100,000-square-foot wing for contemporary art and design, plus 26,000 square feet of exhibition space and the state-of-the-art Amphitheater Hot Shop for glassmaking demonstrations. According to the museum’s most recent annual report, 460,000 people toured CMoG during 2016.

Louis Comfort Tiffany (1848-1933), the son of Charles Tiffany, founder of Tiffany & Co., studied academic painting as a young man. In the late 1870s, he launched a commercial venture to produce high-end art glass, related decorative arts and interior decoration. He structured his extensive business variously over the years and conferred upon it different names, with Tiffany Studios (1902-32) being the most long-lived and famous iteration. His associated production companies included Tiffany Furnaces, Inc.

In homage to the enterprise created by the genius artistic designer and retailer, the exhibition’s two main galleries are suggestive of a Tiffany Studios showroom and workroom. Conway pointed to some of the exhibition’s interesting design touches, among them a window in the Showroom gallery that allows visitors to look upon CMoG’s ancient Roman gallery and the types of mosaics and glass with iridescent surfaces that inspired Tiffany.

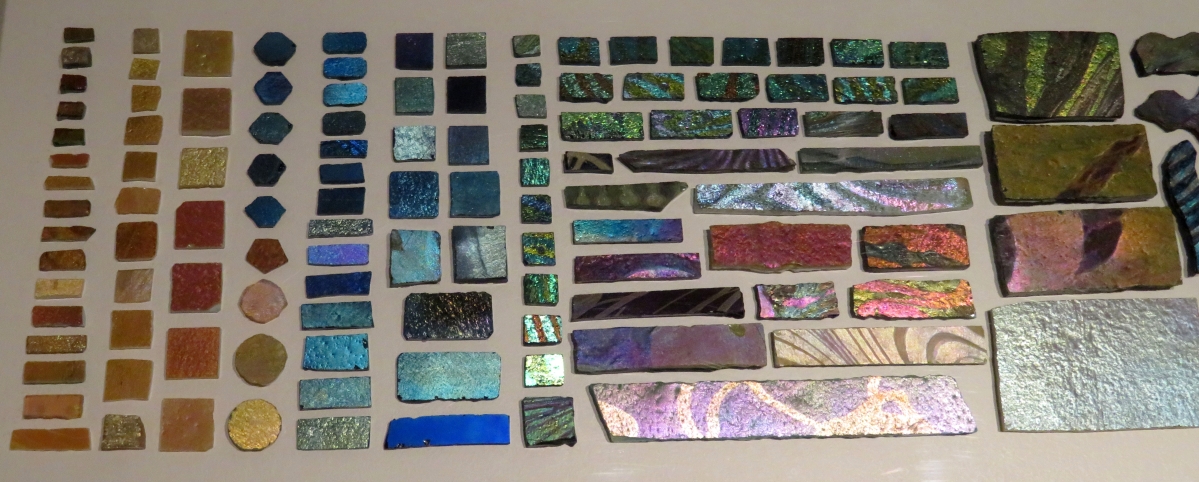

The nearly 50 objects on view from public and private collections include a desk set, tea stands, lamps, clocks, fireplace surrounds, panels, columns, watercolor drawings and archival materials. In contrast to most other forms of art glass, the mosaic with its solid backing is an opaque medium dependent on reflected, rather than transmitted, light for effect. Therefore, surface texture, along with pattern and color, is key. Conway noted that a greater range of glass types could be used in mosaics than in windows or blown vessels. A broader palette was available as well.

One of the most intriguing features in an exhibition filled with wonders is the assemblage of approximately 1,000 glass sheets, fragments and “jewels” relating to mosaic work that were once part of the raw materials stock belonging to Tiffany Studios. This subset is part of a cache of more than 250,000 pieces of glass auctioned in 1937, a few years after the firm closed. Dr Neustadt acquired the trove three decades later. It is now part of The Neustadt’s archival collection.

Parrott noted how the display of such material brings to life the enormity of the task Tiffany glass selectors faced. “They looked at more than a million pieces and had to make a million aesthetic choices. It illustrates how selectors got to work.”

Left, detail of mural, “The Dream Garden” by Tiffany Studios, 1916, for Curtis Publishing Company Building (now The Curtis Center & Dream Garden). Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Right, blown and cut glass murrine by Tiffany Furnaces, Corona, N.Y. The Neustadt Collection of Tiffany Glass.

As part of the “Tiffany’s Palette” program offered in the Amphitheater Hot Shop, visitors can see the Hot Glass Demo Team making sheet glass using the same technique employed by their Tiffany counterparts a century ago. Team members replicate the process of rolling out and ladling a cylinder of glass, which they then open and flatten. The resulting sheet resembles the Tiffany examples in the exhibition that were originally destined to be cut into tiles. Similarly, media presentations illustrating relevant processes run on screens artfully incorporated into the Workroom gallery.

Drawing attention to some of the remarkable art objects on view, Parrott emphasized the importance of The Neustadt’s “Fathers of the Church” along several dimensions. The earliest object in the exhibition, the 8-foot-high panel was created for display at the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago, making it important historically. It was also the first piece made by the women’s glass cutting department at Tiffany Studios. L.C. Tiffany loved it so much that he brought it back with him to Tiffany Studios and used it as a “calling card.” He eventually took it with him to his home Laurelton Hall on Long Island as “a symbol of some of the best work.” Parrott added that due to the fragility of the panel, this is the last time it will travel.

Conway described a plaque depicting peonies in CMoG’s collection as “small but full of so much vivid information and relating to other objects Tiffany made.” To illustrate the point, the plaque is displayed with a grouping of Tiffany vessels illustrating different surfaces. Conway told how conversations with scientists, conservators and glassmakers at CMoG revealed the extensiveness of glass types Tiffany Studios used in mosaics. The plaque also represents an initial collaboration at Tiffany among the furnace workers, chemists and artists hoping to achieve a certain effect.

“The complexity in producing the glass surprised us. It’s not just the colors and textures, but also the skill of the glass cutters. The peony’s petals are so wispy and delicate. The shapes and cutting skill give a sense of the flower,” Conway said.

Two fireplace surrounds appear in the show. Conway commented on the role of the product in broadening Tiffany’s market, albeit still within the category of “luxury goods.” Her investigation of business papers at the Charles Hosmer Morse Museum of Art in Winter Park, Fla., revealed that Tiffany conducted a robust business in this form, an option for those consumers who might not be able to afford outfitting their whole residence in Tiffany glass.

Reredos by Tiffany Glass Company or Tiffany Glass and Decorating Company, designed by Jacob Adolphus Holzer (1858–1938), 1891. St Paul’s Episcopal Church, Troy, N.Y.

“The fireplace surrounds humanized mosaics and surprised me in a delightful way. They help us tell the story more fully because they involve homes. They are much more personal and … very different from designs made for public spaces,” the curator noted.

Inherent in mounting an exhibition on this topic is the challenge of showing murals and other decorative elements that could not be transported to Corning. The solution came in the creation of the Mosaic Theater. Its multimedia presentations represent a dozen Tiffany commissions in the Northeast and Midwest. These include “The Dream Garden” after a painting by Maxfield Parrish (1870-1966), Curtis Publishing Company Building (now the Curtis Center & Dream Garden), Philadelphia; “Heroes and Heroines of the Homeric Story,” Alexander Hall, Princeton; “Jacques Marquette’s Expedition,” Marquette Building, Chicago; and the interior decoration of St Paul’s Episcopal Church, Troy, N.Y.

As an essential first step, CMoG staff undertook extensive overall and detail photography of the mosaics, some of which had never been professionally photographed. According to Conway, the media presentations not only provide architectural context for the murals, but also allow visitors to experience “them up close and at eye level. We think that people should see them in situ, but also come to Corning to see them in detail.”

Many of the beautiful photographs also appear in the 272-page publication accompanying the exhibition. Aside from its six detailed essays by Conway, Parrott and other glass experts, the volume contains “A Chronology of Tiffany Mosaics” compiled by Morgan T. Albahary. This inventory lists the location and, if known, status of more than 200 mosaic schemes Tiffany executed between 1879 and 1931. Parrott lamented, “It is striking how many works have been lost. We wanted to highlight the vulnerability of the surviving pieces. Their caretakers should know that there are resources out there and others who are interested in them.”

In keeping with the inventive spirit of Tiffany, team members have expanded and enhanced what is a medium-sized exhibition in “footprint” with media presentations, live glassmaking demonstrations, a scholarly publication, art classes, a three-day symposium planned for October 19 to 21 and a Tiffany driving tour, details of which are posted on CMoG’s website.

Conway stated that she, Parrott and their colleagues in this effort want to promote “a heightened awareness for mosaics. They were a large part of Tiffany’s business. Through both the exhibition and publication we want visitors to have a deep appreciation of the innovation he brought to mosaics.”

The Corning Museum of Glass is at One Museum Way. For information, 800-732-6845 or cmog.org.

Kate Eagen Johnson is an expert in American decorative arts and an independent museum consultant, historian, lecturer and author.