French M-1766 cavalry pistol, Royal Manufactory at Maubeuge, 1774. Walnut, iron, steel and brass. Museum purchase. Photo courtesy of The Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg.

By Kristin Nord

WILLIAMSBURG, VA. – On the cusp of the American Revolution, Williamsburg was the capital of Virginia and home to many prominent men who supported the cause of American liberty. It was also the setting for a gunpowder incident that exacerbated calls for war.

Tensions arose on Friday, April 21, 1775, when Virginia’s last royal governor, Lord Dunmore, gave orders to Captain Henry Collins of the armed schooner Magdalen to remove 15 barrels of gunpowder from Williamsburg’s Magazine. Militia companies mobilized quickly, setting up camps in town. The incident led to the establishment of an interim government and the raising of regiments within the colony. When an express rider arrived on April 28 with news of the first shots at Lexington, it became official. The Revolutionary War had begun.

It is against this historical backdrop that “To Arm Against an Enemy: Weapons of the Revolutionary War” opened this spring at the DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum as the first of three exhibitions that will run through December 31, 2022. Curated by Erik Goldstein, an expert in antique weaponry and the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation’s senior curator of mechanical arts and numismatics, the show draws upon the foundation’s renowned arms collection for this survey of the muskets, carbines and rifles, bayonets, pistols and swords used in battles on land and at sea.

At the outset of the war, colonists were wielding what Goldstein describes as “an international jumble of firearms and bladed weapons;” without the ability to mass manufacture arms, they relied initially on what was readily available or could be assembled from old and locally made parts.

Rebels were up against arguably the finest military force of the era, Goldstein said, and contrary to myth – (“There’s an awful lot of bunk about this war,” Goldstein commented recently, after giving a lecture at the Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia) – Americans would prevail, not through frontier skirmishes but by mastering the tactics of Eighteenth Century linear warfare.

The workhorse in battle was the smoothbore musket, which was accurate at short range of under 80 yards. Its most famous version was the British Brown Bess, which was issued to British soldiers well into the Nineteenth Century. When coupled with a fitted bayonet, soldiers could both shoot and stab, though not at the same time.

Matthew H. Spring, in With Zeal and Bayonets Only, notes that it was a truism that a battalion’s first fire was the most destructive. “This was because the soldiers had carefully loaded this round before the action, their barrels were clean, their flints were sharp, and their field of vision was clear of powder smoke.”

Overall, rapidity of fire was much more important than the accuracy of anyone’s musket – and discipline was crucial when opponents were facing off in tight formation.

In battle, it was common to find British Short Land Pattern of 1769 muskets used alongside long patterned ones, while other patterned muskets were modified for use at sea. Additionally, once hostilities began in spring of 1775, a huge number of Irish units embarked to American service and fought with the Dublin Castle Pattern 1769 muskets.

Today some of the most valuable Brown Besses are those that bear markings from specific regiments, Goldstein notes, in an identification guide for The Brown Bess that he co-authored with Stuart Mowbray. The more historical the regiment, the more intriguing the musket, and the ones most commonly encountered are those that belonged to regiments that laid down their arms after major battles.

Pattern 1769 land service musket, Board of Ordnance, London or Birmingham, England, circa 1769–75. Walnut, iron, steel and brass. Museum Purchase. Photo courtesy of The Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg.

While it was common for the British to smash the stocks of their muskets after they were defeated, American armorers soon became adept at salvaging what was left of them. “Whether damaged or not, these captured Brown Besses provided a flood of locks, barrels and other parts that would be used in American gun construction for many years,” Goldstein said.

Lesser-quality muskets from Liège, Belgium were used in battle, and after the Battle of Saratoga in 1777, when France joined the war as a formal American ally, first-rate French modern firearms and edged weapons were added to a mix. A French musket on display bears a United States brand on the stock, indicating it belonged to the Continental Army.

Two French bayonets on display illustrate the degree to which designs were evolving; one was faulty and quickly discarded, while the second, an infantry bayonet with a mid-socket locking ring proved so superior that it was widely copied by other countries and remained in use until the end of the Nineteenth Century.

In contrast to muskets, rifles required special fine-grained gunpowder for the flash pan. Rifle balls were wrapped in oil cloth patches so that they would fit the barrel tightly enough (to all the spiral grooves) to impart spin to the ball. It was this spin that made the rifle considerably more accurate than the musket. Rifles (or fusils) could be lethal in the hands of sharp-shooting Hessian mercenaries, who fought for the British in their own distinctive units. But this weapon, while it afforded greater accuracy, took too long to load. And rifles could not be outfitted with standard bayonets, so their usefulness was restricted.

Officers on both sides carried weapons similar to their troops, but they were usually of finer quality and more ornately designed.

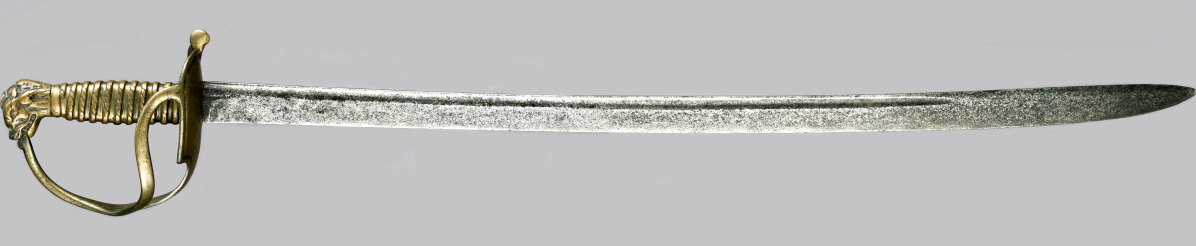

As musket and bayonet warfare proved effective, infantry swords essentially became uniform accessories, worn by grenadiers, sergeants, musicians and officers. Ornately embellished weapons signified status and reflected trends in fashion. They were “the fancy wristwatches” of the time, Goldstein said.

Officer’s saber and scabbard, James Cullum, London, circa 1775. Steel, iron, gilt brass, wood, copper and leather. Museum purchase. Photo courtesy of The Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg.

Some distinctive swords in this show include a basket-hilted hanger made for the grenadiers of The First Regiment, an elite British regiment; and an infantry hanger and scabbard made for the Royal Welsh Fusilier unit that served in America from 1773 to 1783. The latter is among the 24 identical examples that once formed the Eighteenth Century arms display at Flixton Hall, in Suffolk, England.

One of the more popular designs of the period can be seen in the officer’s saber, dated circa 1775, with its distinctive lion’s head pommel, slotted “d” guard and copper wire and tape grip. Another coveted weapon is a scimitar-bladed saber, one of 1,600 produced by James Potter of New York for the Loyalist dragoons. These swords were so desirable that the Continental Dragoons captured them for their own use whenever possible, Goldstein said.

As the fighting shifted South, mounted units became more important. By the end of the war there were thousands of light dragoon soldiers who fought solely from the saddle. This was the only soldier who relied upon his sword as a primary weapon, notes the exhibition’s wall text. He also used carbines and pistols, like the pattern 1759, which was one of the most common pistols carried by mounted troops fighting on both sides.

Over time, a nascent arms industry blossomed in Virginia, and Rappahannock Forge, located in Falmouth and overseen by James Hunter, would become the most important of its kind in America. Its massive compound, which included a brass foundry, furnaces, iron rolling and slitting mills and shops for coopers, wheelwrights, saddlers and millers would serve as a template, Goldstein said, for arsenals in Harper’s Ferry and Springfield, Mass.

There are a number of rare weapons of particular note in this show, foremost among them a silver-hilted smallsword believed to have been presented to Nathanael Greene on the occasion of his promotion to Commander of the Southern Department of the Continental Army in 1781. After Greene’s death in 1786 it was embellished with two roundels set onto the grip, one of which bears the engraved date and presentation to General Greene, and the second, a miniature enamel portrait set in a reeded bezel, that is based upon the famous 1783 portrait painted by Charles Willson Peale.

-1024x321.jpg)

Silver hilted smallsword, London, England and America, 1765–70. Silver, iron/steel, wood, enamel and traces of gilding. Museum purchase and partial gift of Patty Voght in memory of Thomas G. Wnuck. Photo courtesy of The Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg.

Another fascinating artifact is an Indian Trade fusil, attributed to John Bumford and dated circa 1755, believed to be the sole surviving example from the mid-Eighteenth Century, with its paint decoration still visible.

And of particular local interest is a British heavy cavalry saber that was found in the 1940s poking through the leaves on farm property just a few miles south of Williamsburg. This specimen is similar to the “Figure of 8” cutlasses that were issued to the Royal Navy throughout the Eighteenth Century.

In the months ahead, Goldstein will expand upon this story, and the material from all three exhibitions will form the basis for a permanent installation in the future, he said. Next up Goldstein will help visitors learn about the artifacts recovered in Williamsburg archaeological excavations. The final show will delve into the accoutrements of warfare, including the importance of military music on the battlefield. One can expect the celebrated Colonial Williamsburg Fife and Drum Corps will have an active role in that.

The exhibition was presented with generous funding from the The Pritzker Military Museum & Library.

The Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg are located at the intersection of Francis and South Henry Streets. For more information, www.colonialwilliamsburg.org or 855-756-9516.

.jpg)