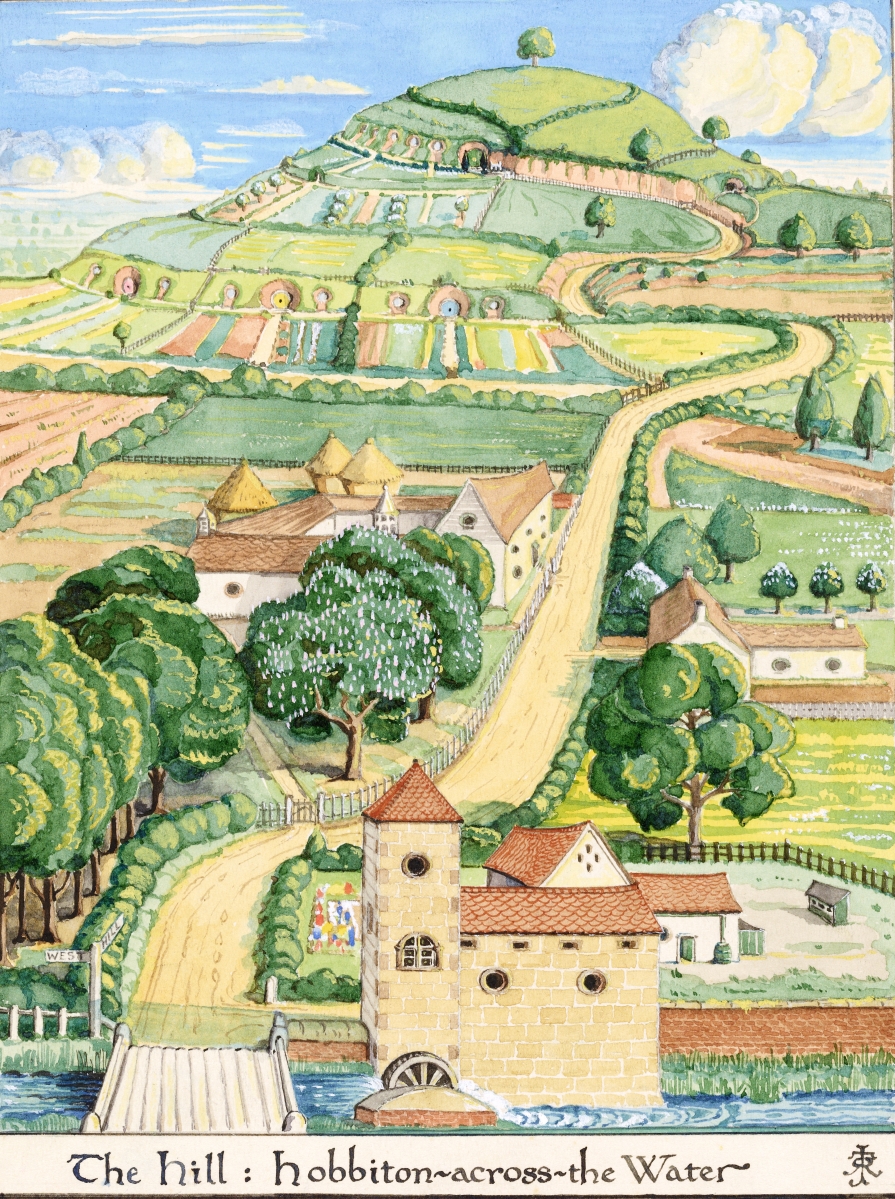

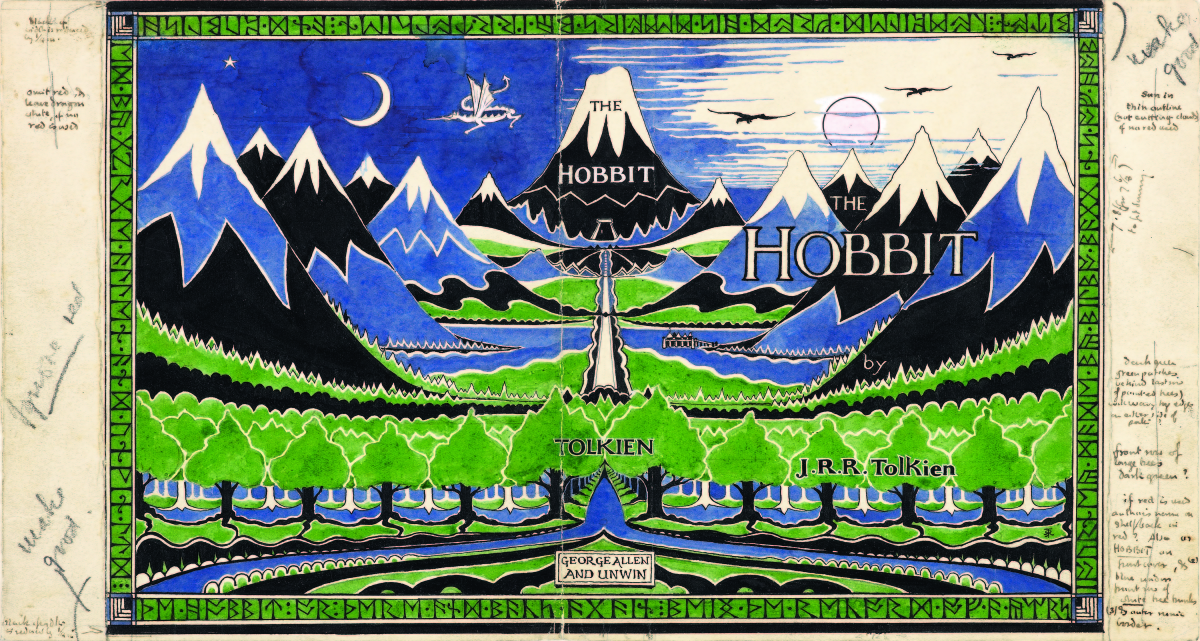

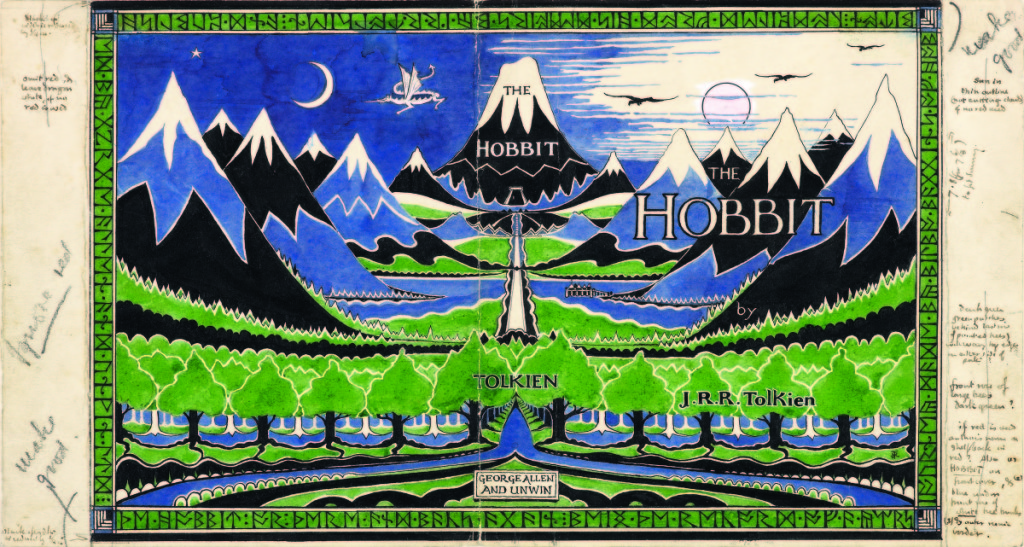

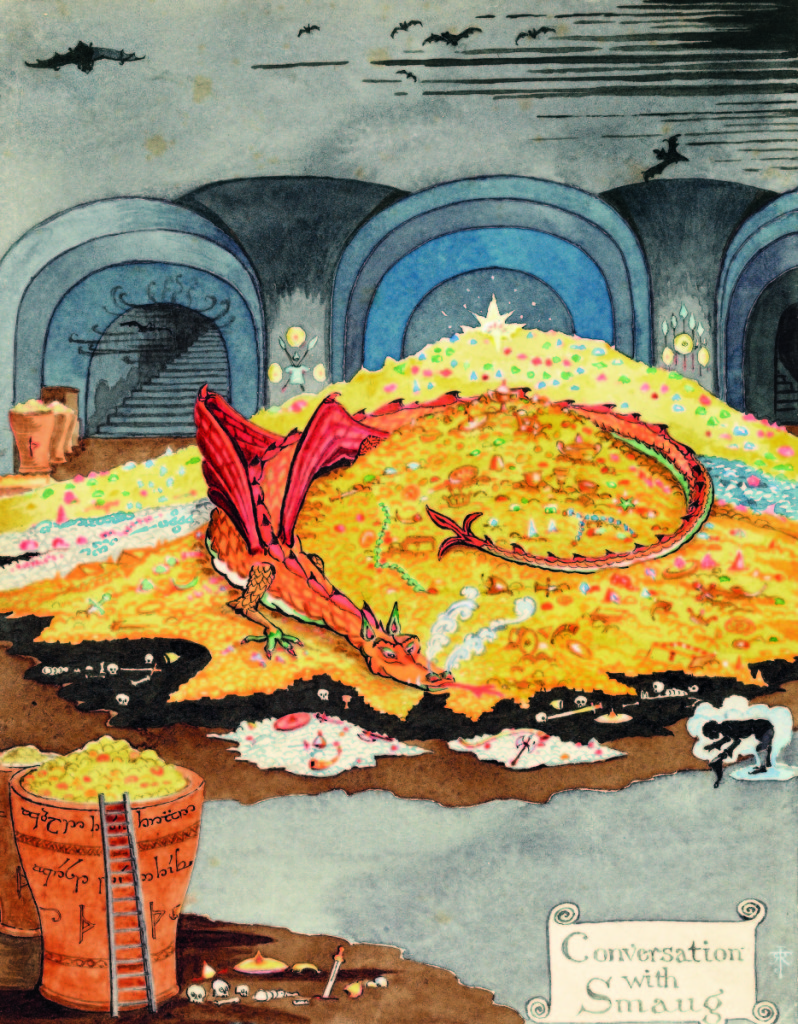

Dust jacket design for The Hobbit by J.R.R. Tolkien, April 1937. Pencil, black ink, watercolor, gouache.

Bodleian Libraries, MS. Tolkien Drawings 32. ©The Tolkien Estate Limited 1937.

By James D. Balestrieri

NEW YORK CITY – To spend your life, as J.R.R. Tolkien did, creating fantastic worlds, worlds that draw upon, transform and transcend the mythologies of Ancient Britain, Ireland and Wales, grafting them onto the Icelandic Saga tradition and the Old Norse and Germanic tales, you have to hold fast to two beliefs: one, that words have a power all their own, that they shimmer and reverberate with their own histories and etymologies, and two: that a magical, golden past age – even one that cannot ever be visited, one that, perhaps, never existed – can, through the careful building of words, word upon word upon word, be made visible, manifest and tangible.

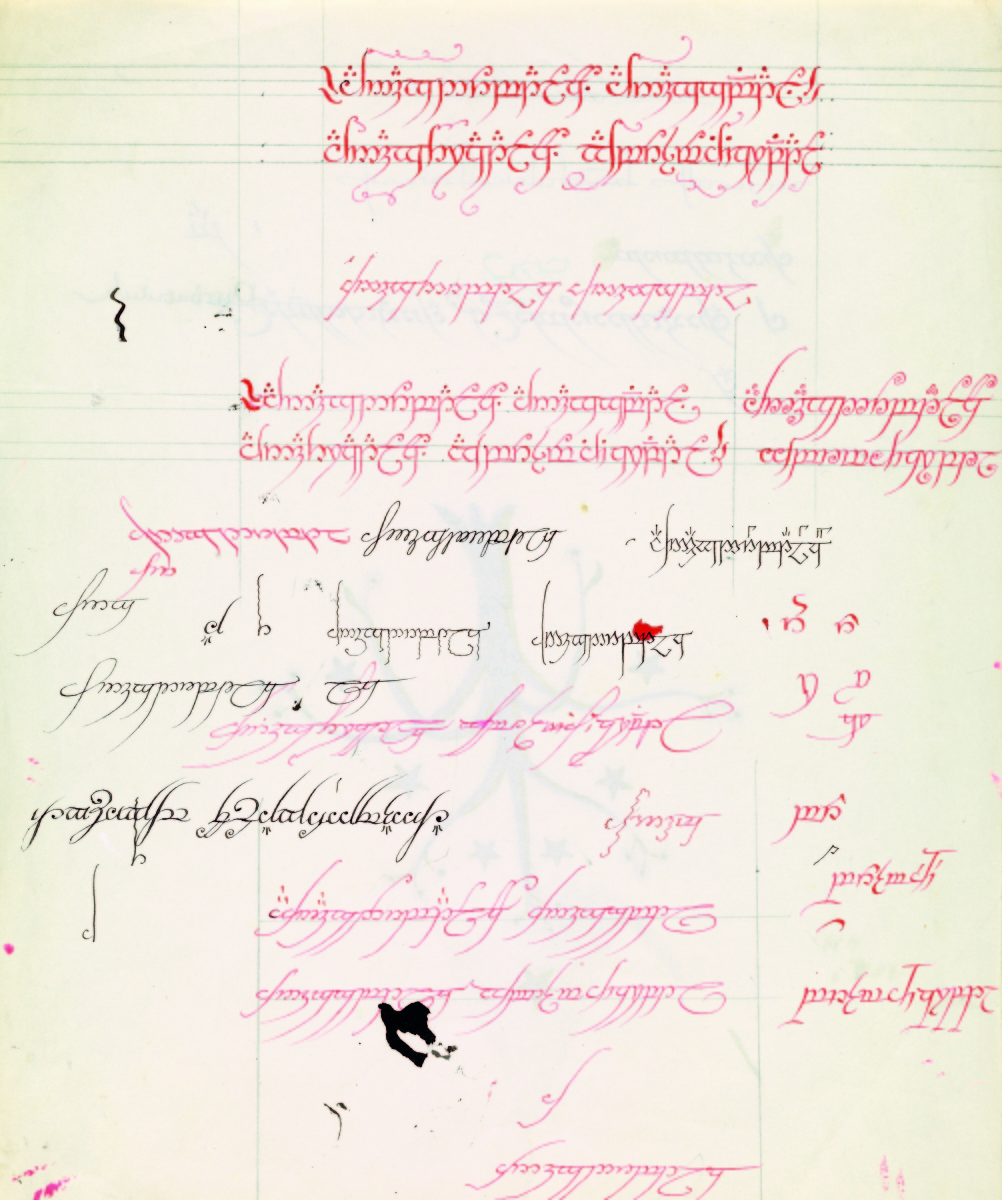

If you have never read The Hobbit or The Lord of the Rings or seen any of the films, or if elves, orcs and talking trees don’t do anything for you, “Tolkien: Maker of Middle Earth,” at the Morgan Library in New York might not be your cuppa. But if you have put in the time and given serious thought to learning Elvish, or if you simply want to know more about how a masterful philologist combined his passion for comparative linguistics with a strong visual sensibility and went on to construct one of the most enduring literary worlds of our time – or any time – this exhibition is made for you.

“In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit.” So begins The Hobbit, the first of Tolkien’s Middle Earth works to be published, in 1937. Famously, Tolkien, bored with correcting examination papers, wrote that opening line on the back of some poor student’s work and made it the foundation of a story he told his children. But the line was more a culmination than a beginning.

Languages and mythologies and what he would come to call Faërie – a word that Tolkien scholar Verlyn Flieger, in the catalog that accompanies the exhibition, calls “the most potent” in his “imaginative lexicon” – occupied Tolkien’s mind from an early age. For Tolkien, as Flieger sees it, Faërie is a realm, a state of being and an atmosphere. Through the “glamour” of words – glamour here having its earliest meanings: “magic, enchantment, spell,” as well as being related, as Tolkien well knew, to the word “grammar.” In Tolkien’s mind, view and writing, Faërie was a real dreamworld, yoking and then discarding the contradiction in that idea. I wonder if he saw himself more as scribe than author, accompanying Bilbo and Frodo, quill in hand, as they venture out from the safety of home, moving from being to doing, from living to acting, into the wide wilds of Middle Earth, where decisions do not wait upon deliberations.

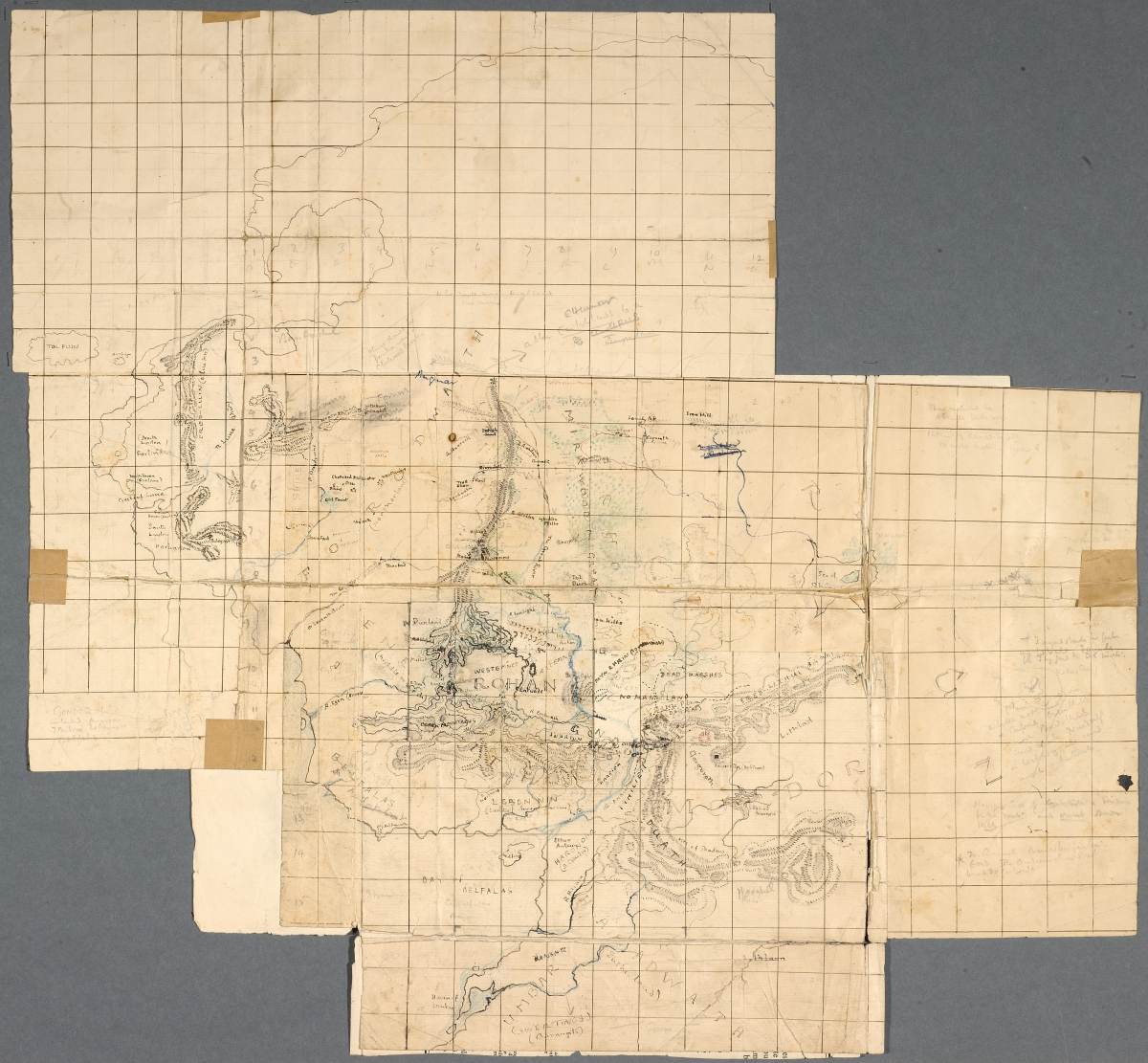

Among the many fascinating objects in the exhibition – letters, photographs, fan mail (a letter from Chuck and Joni Mitchell on their independent use of the word “Wilderland” is good fun) and pieces of drafts, those that show how Tolkien saw and heard Middle Earth, the written and spoken languages he devised, and his paintings, drawings and maps of the Faërie realm, are of particular interest. Having just visited and written about J.K. Rowling’s magic at the New York Historical Society’s exhibition, “Harry Potter: A History of Magic,” I see the similarities of mind between the two authors. Tolkien and Rowling pay close attention to the smallest detail while ensuring that those details make sense in a grand, overarching plan. And one other thing: each has a flair – an ear, really – for creating the correct names for characters. It is a skill that can only come with a deep understanding of and passion for the sounds and meanings of words. In the catalog entry beside a beautiful poem and letter he wrote to a 7-year-old fan of The Hobbit, Rosalind Ramage, Tolkien, in an interview in 1964, said, “I always in writing, always start with a name. Give me a name and it produces a story.” Could Gandalf be other than Gandalf? Could Dumbledore be other than Dumbledore?

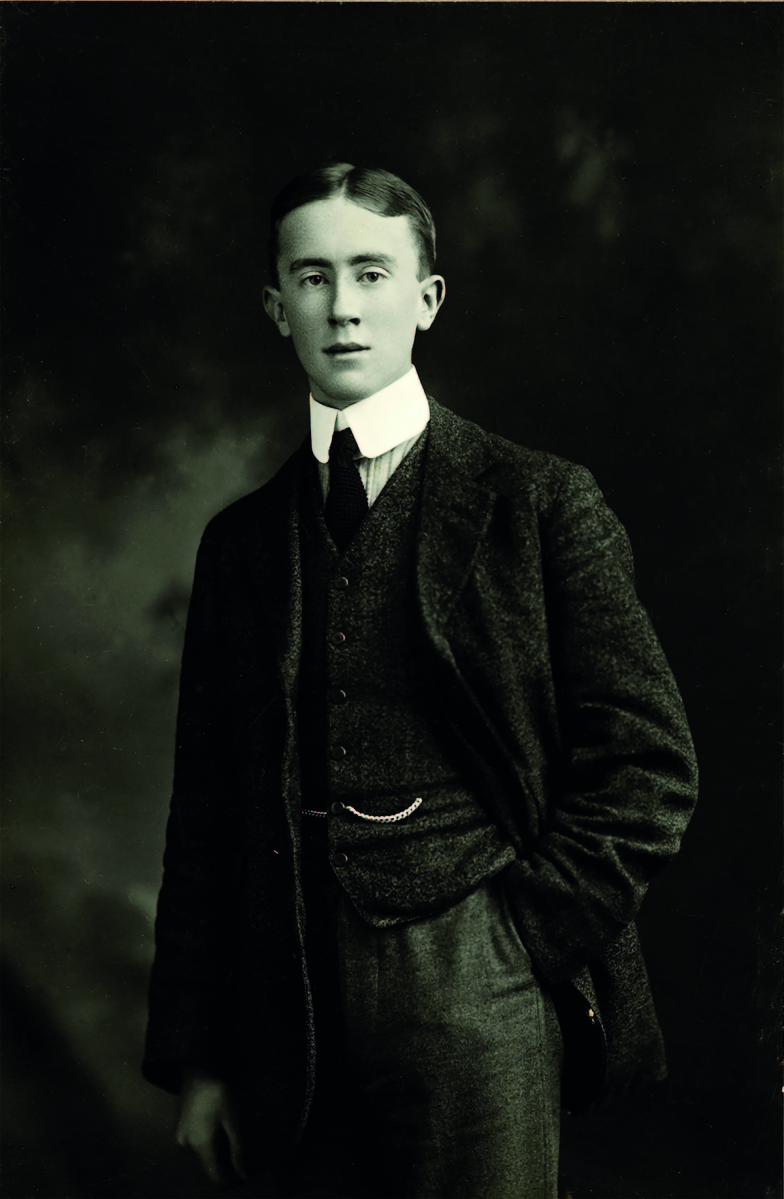

J.R.R. Tolkien was born in South Africa in 1892. When his father died in 1896, Tolkien’s mother settled in England. When she, too, passed away in 1904, Tolkien and his brother were entrusted to the care of a Catholic priest and sent to live with one of their aunts. Tolkien, who was called Ronald, showed an early aptitude for languages and formed a club, the Tea Club and Barrovian Society, with three friends, dedicating themselves to beauty, art and moral rectitude, and pledging to “use their individual talents to create a better world.” Soon after, he would meet his future wife, Edith, embark on his studies at Oxford, and begin to train for service in Britain’s armed forces after the guns of August, 1914, began to boom.

Two of Tolkien’s Tea Club friends would perish in the war and Tolkien himself would be sent home with trench fever. This experience shaped his skeptical view of mechanized war in a mechanized world. After the war, back at Oxford, he would find kindred spirits in another group, the Inklings, whose ranks included C.S. Lewis, of Narnia fame. At these meetings, held in a pub, the members would read their works and critique one another. Middle Earth took shape at these gatherings.

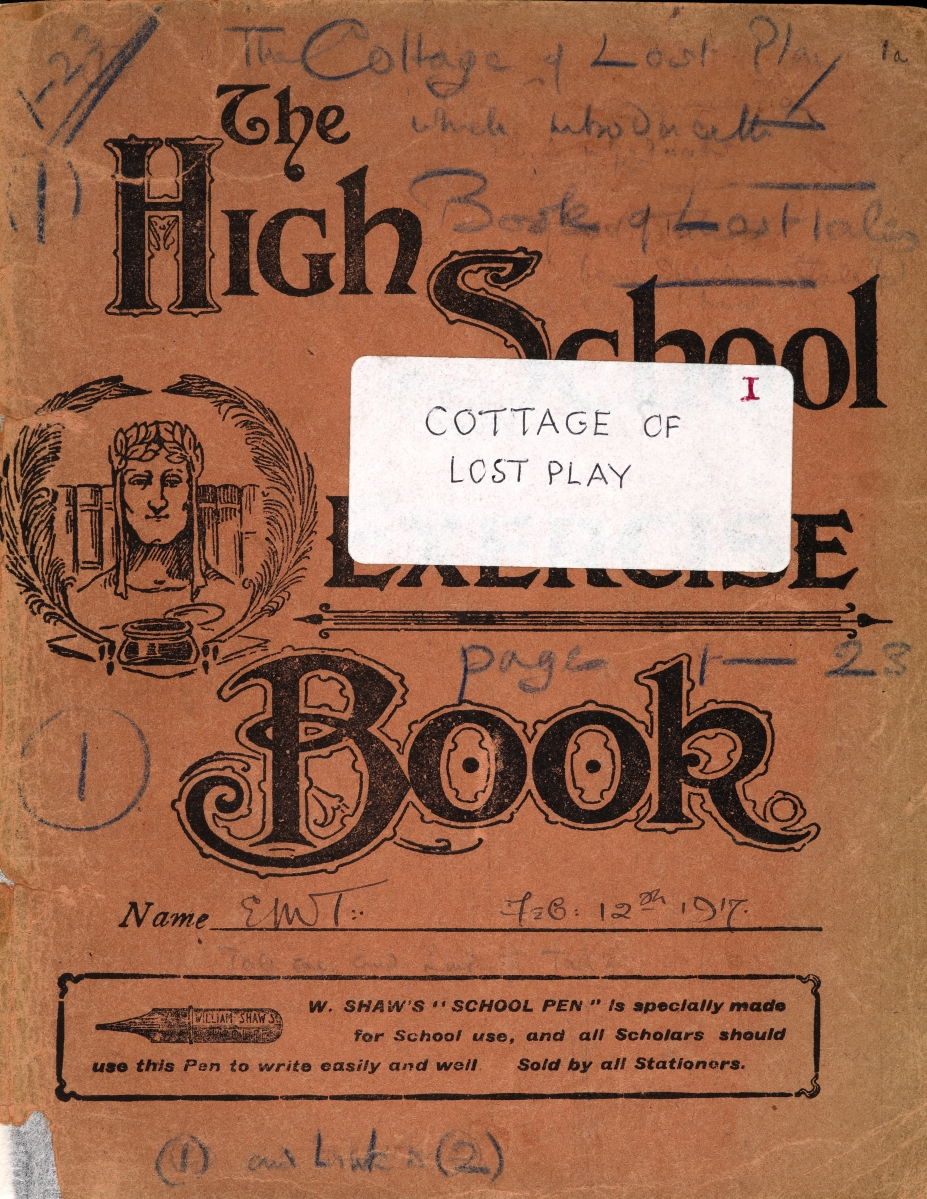

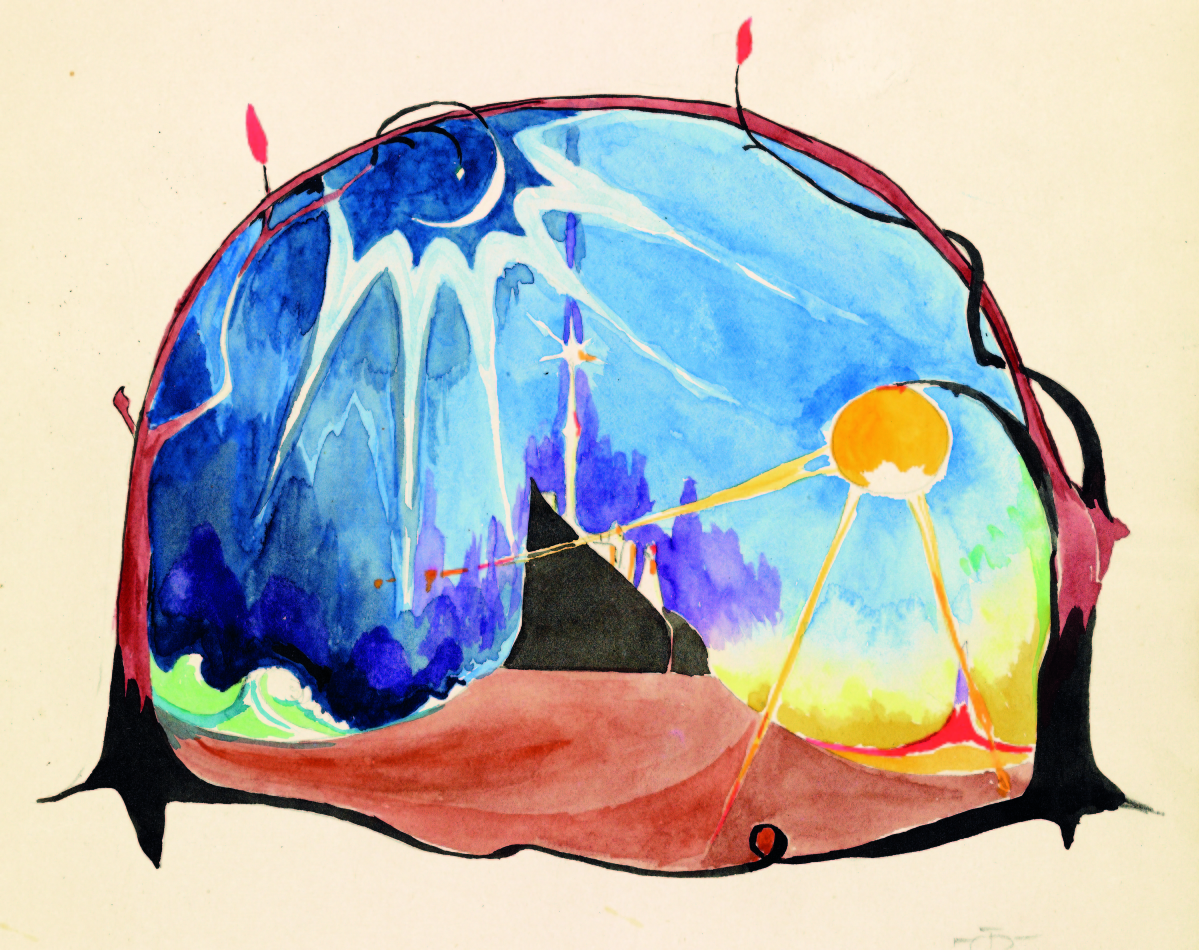

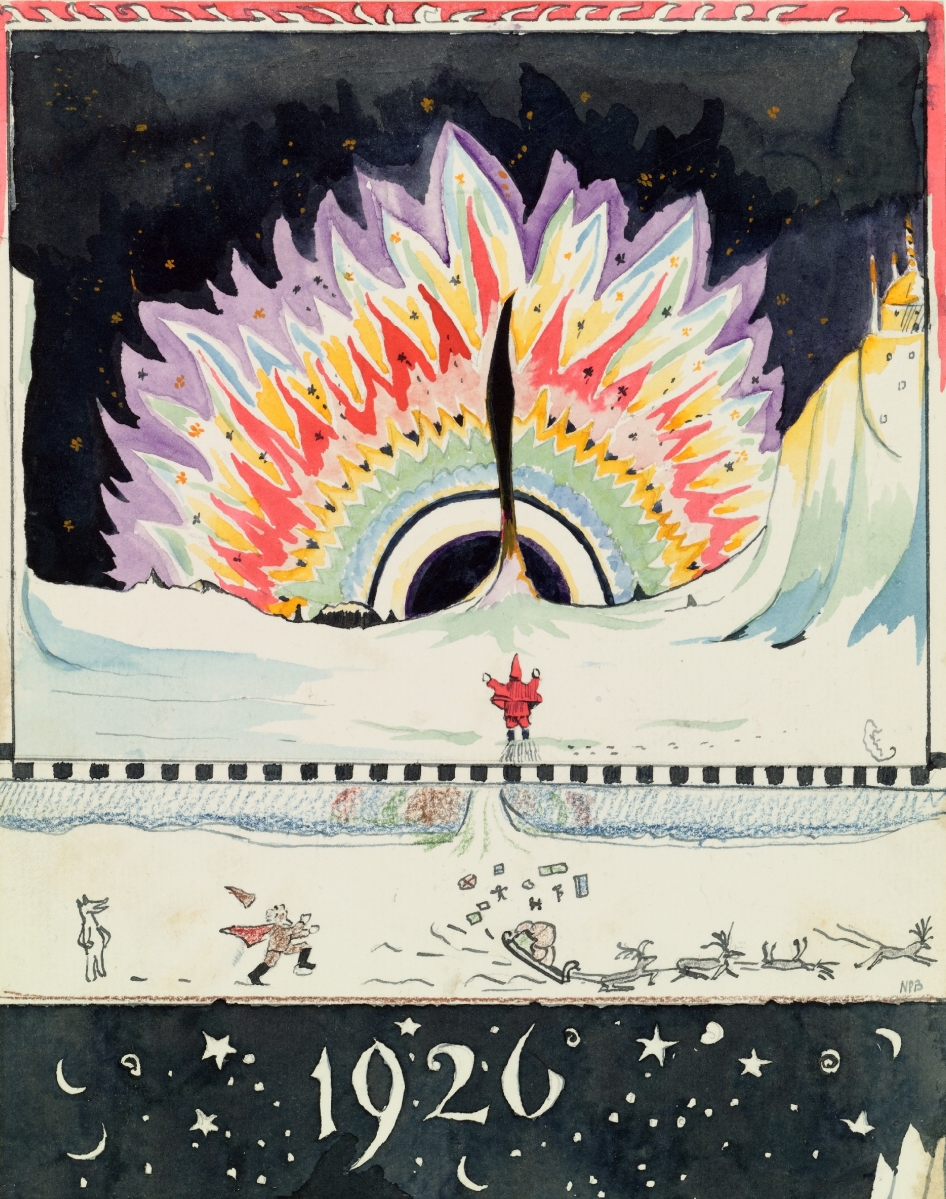

But all the way back in 1914, Tolkien had begun to keep a sketchbook he called “The Book of Ishness.” In it, he would draw and paint imaginative, almost expressionistic works, each one emblematic of some state of being or mind, with titles such as “Undertenishness,” “Eeriness,” and the psychologically resonant, “Beyond” and a related watercolor, “There (when you don’t want to go from here) & Here (in an exciting place).”

In each work, “There” is a distant mountain range, while “Here” is a copse of three geometric trees. The forest, for Tolkien, would be “there,” outside and away from the more pastoral home. But three trees, with its suggestion of the Trinity, is shaded but not shadowed, even haloed (hallowed?) in “There & Here.” But where “There & Here” are not connected, “Beyond” connects the two realms with a blood red road that crosses an abstract river. The journey is not just necessary, it is physical, intrinsic and arterial.

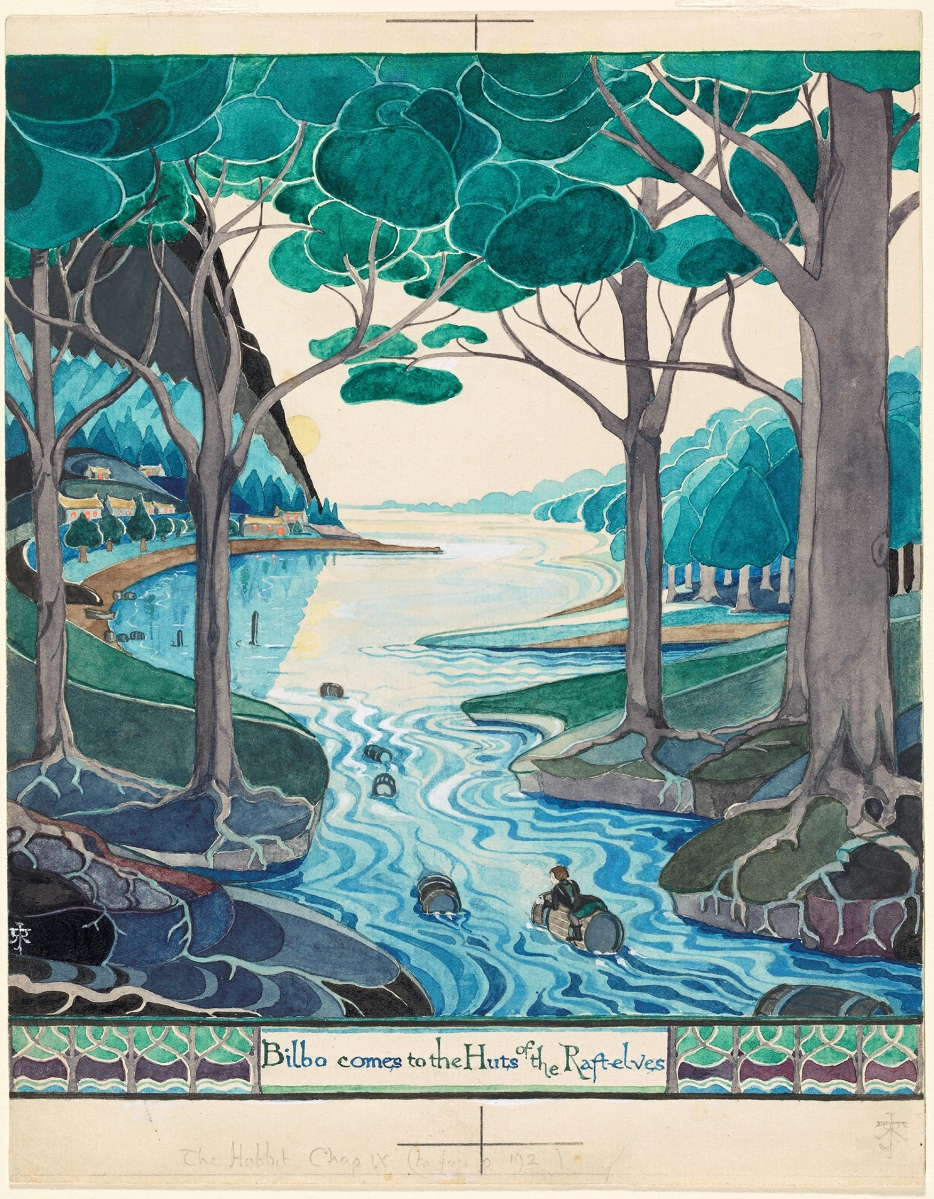

This connectedness, this interwoven continuum flowing between forms, between there and here, shines through all of Tolkien’s paintings and drawings for The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings. In his gorgeously colored paintings, many of which would become illustrations for the stories, paintings like “Bilbo Comes to the Huts of the Raft-Elves” and “The Hill: Hobbiton Across the Water,” “there” and “here” are both separated and linked by a flowing, winding river. These elemental roads, as Tolkien conceives them, foreshorten and, at last, eliminate the distance between them. There is Here; Here is There.

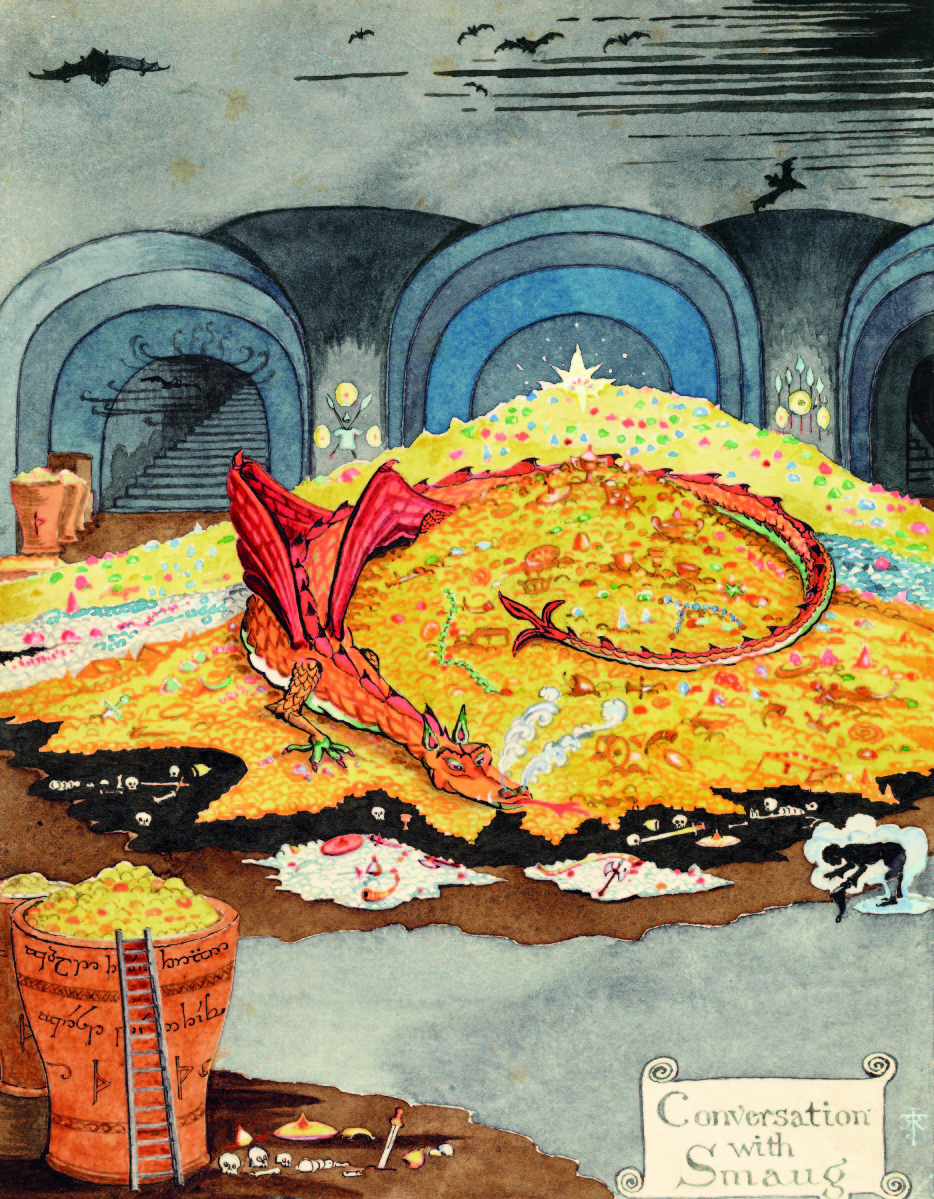

Tolkien organized his works around the cosmogonic, universal myth of the quest. In The Hobbit, the quest is to restore the Dwarves to their kingdom under the mountain, and its vast wealth, by ridding the mountain of an enormous gold and gem fevered dragon – the wonderfully smug and smoggy Smaug, seen in the exhibition in what is perhaps Tolkien’s most illustrative piece, “Conversation with Smaug.” In The Lord of the Rings, the quest is to destroy a ring of absolute power – that corrupts absolutely – by hurling it into an active volcano that happens to be the seat of the darkest of dark demons, Sauron. In both works, the forces of light must array themselves to do battle against the forces of darkness.

“Conversation with Smaug,” by J.R.R. Tolkien, July 1937. Black and colored ink, watercolor, white body color, pencil. Bodleian Libraries, MS. Tolkien Drawings 30. ©The Tolkien Estate Limited 1937.

If There is Here, then the quest is, at least to some extent, foreordained. Combine this Catholic tenet with Tolkien’s keen interest in the fatalism and Götterdämmerung ending in Norse Mythology’s last lost battle, Ragnarok, and you arrive at the end of the time of the Elves, and the rise of the time of Man. Human beings, in Tolkien’s writings, are an easily corrupted species, with exponentially greater penchants for Elvish vanity and Dwarvish greed.

At some point, someone should do a comparative study of Tolkien’s artwork with the World War I watercolors of Claggett Wilson and those of Charles Burchfield that seek to communicate the immanence, the glamour and grammar, if you will, of the natural world. The flow of forms I mentioned earlier, the connectedness and sense of continuum between disparate and diverse forms you see in Tolkien is equally prominent in Wilson’s scenes of bloody trench warfare and in Burchfield’s secret, wooded wonderlands. Perhaps it is merely a matter of all three living at roughly the same time, living through the same period. A Zeitgeist thing, Jung would say. Perhaps it is just the way that watercolor was taught then. While it is tempting to attribute his interest in Faërie to a desire to leave the war behind (just as one might say Wilson’s deep dive into the images the war made indelible in his mind might be oversimplified as cathartic), Tolkien began his quest years before the war. Burchfield did not serve, but sought not only to paint nature as he saw it, but also as he heard it – as all his senses perceived it. Like the runic motto of the Ring of Power, revealed only in fire, the three of them, Tolkien, Wilson and Burchfield, seem to want to stand behind these dark and diaphanous worlds, worlds entirely unto themselves that we cannot, or will not see, and shine a light through them, revealing them to us.

Throughout “Tolkien: Maker of Middle Earth,” the twin bass lines are his friendship with C.S. Lewis, without whose fruitful, frictional encouragement Tolkien might never have seen Middle Earth between covers, and his unfinished and unpublished (in his lifetime) symphony, The Silmarillion, the origin story of Middle Earth. Consider this. If, as Tolkien believed, the glamour of words was the pathway to the reality of dreams, how can those words, even the languages that sprang from his own imagination, have an origin, a beginning, an utterance? “In the beginning was the word,” but is it a word we are meant to know? The message of Tolkien’s unfinished work might be that the one word and the one ring are things we should not know or possess, things that, if we did know or possess them, would have to be carried back and cast back into the fire of creation, lest every universe collapse in chaos.

The Morgan Library & Museum is at 225 Madison Avenue. For information, www.themorgan.org or 212-685-0008.