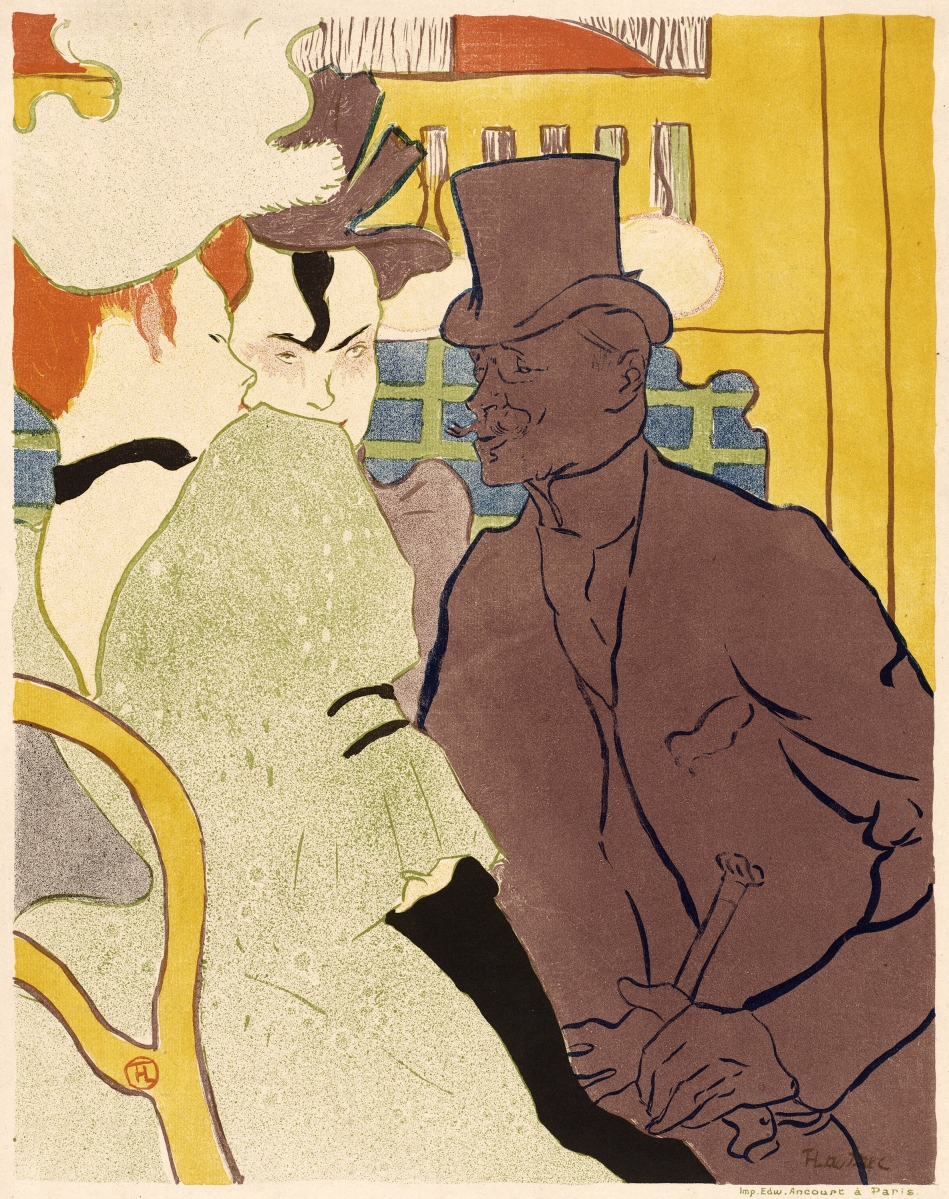

“Aristide Bruant in his Cabaret” by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (French, 1864–1901), 1893. Lithograph. Otis Norcross Fund. Photograph ©Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

By Jessica Skwire Routhier

BOSTON – Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec has long been known for his graphic depictions of Paris nightlife. The works are “graphic” in several senses of the word – not only are they masterworks of lithography; they also unflinchingly show the seamier side of cafés, brothels and cabarets. Unlike today’s airbrushed and Instagrammable images of celebrities, in Lautrec’s world, the stars are – like he himself was – flawed, eclectic, even downright odd. And yet, in Lautrec’s prints, paintings and drawings – and in the works of several other artists featured in the show – it is not at all difficult to see the appeal of these subversive characters and to appreciate how their very oddities contributed to their lasting stardom. “Toulouse-Lautrec and the Stars of Paris” is on view at the Museum of Fine Arts (MFA) in Boston through August 4.

The exhibition is a collaborative effort between the MFA and the Boston Public Library (BPL), a marriage of two enviable collections of Lautrec graphics. The exhibition offers a rare opportunity to see so many of Lautrec’s famed prints and posters together at one time, as well as quite a few of his much rarer paintings and drawings. It also gives visitors the chance to immerse themselves in the world of fin-de-siècle Paris, in all its decadent glamour. Here you will find films by the Lumière brothers, photographs of cabaret performers in costume, corsets and hats and gowns that demonstrate the era’s taste for extreme silhouettes and luxe fabrics, musical instruments, electric lights, postcards, menus and more. The exhibition is less about Lautrec than it is about the world of extremes that he inhabited: the alternately fabulous and debauched demimondaines of turn-of-the-century Montmartre that were both his adopted family and his favorite artistic subject.

The exhibition begins with a gallery dedicated to Lautrec’s origins, both personal and artistic. Unlike many of the performers that would become his closest friends, Lautrec was born to a life of great affluence. His parents were the Comte and Comtesse de Toulouse-Lautrec-Monfa, and “he grew up moving from one château to another,” according to Helen Burnham, the MFA’s curator of prints and drawings, during a recent gallery tour. The Comte and Comtesse were first cousins who may have passed on a genetic disease to their son: by the time Lautrec was a teenager, he had broken both of his legs, and his weakened bones failed to heal properly. As a result, he suffered near-constant pain, had an uneven gait, and was dramatically shorter – about only four foot eight inches – than the average man of the time.

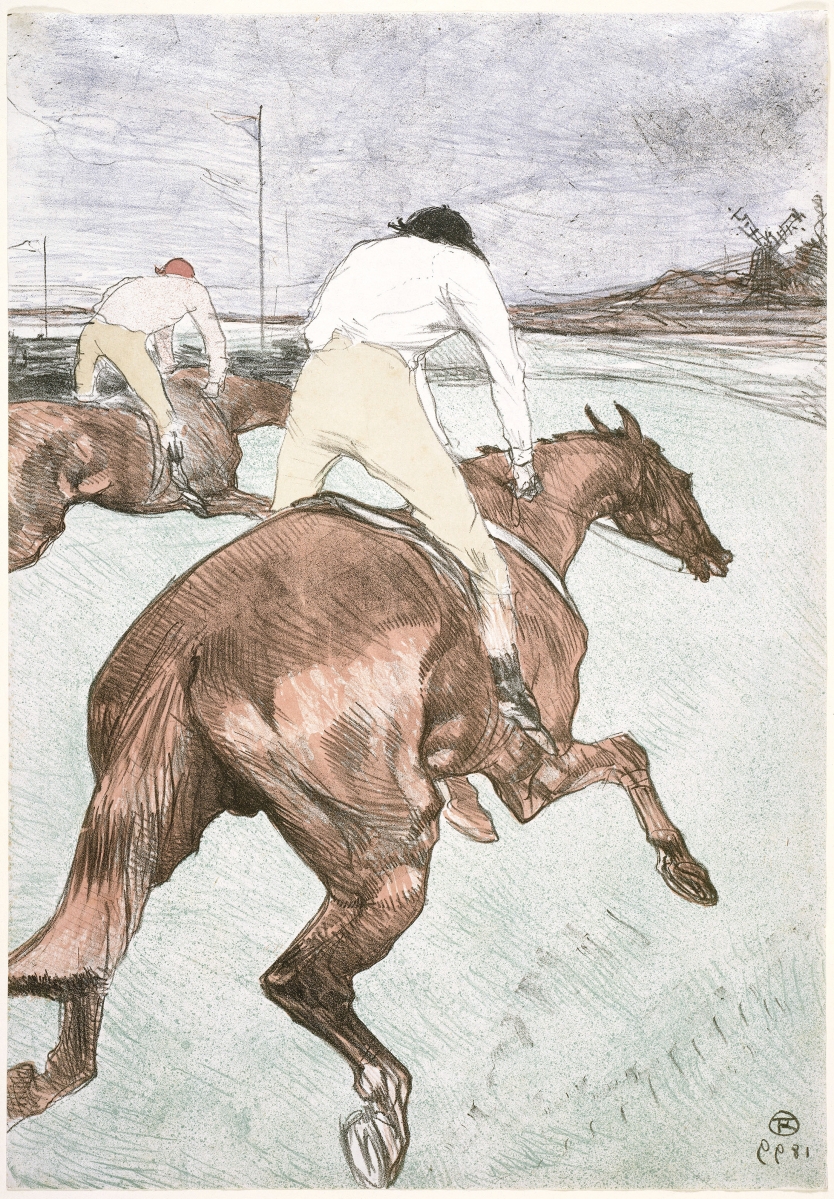

Unable to participate in the athletic pursuits that would have been common for a young man of his class, Lautrec gave himself over to his art – his ability had been noticed and encouraged when he was still a very young child – and also to the practice of being a flâneur, an observer, taking in everything that he saw in the visually rich world of Belle Époque France. One of his long-term fascinations was the horses he saw on the racetracks and the polo grounds. Even though the riders’ faces are obscured in Lautrec’s print “The Jockey,” their taut poses and the clattering, soaring gestures of their horses convey the same sense of movement and expression that Lautrec brought to his depictions of performers.

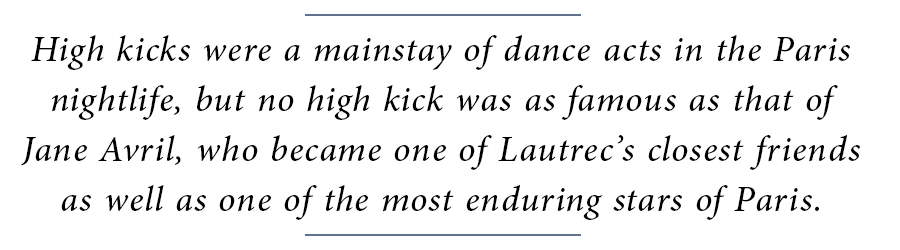

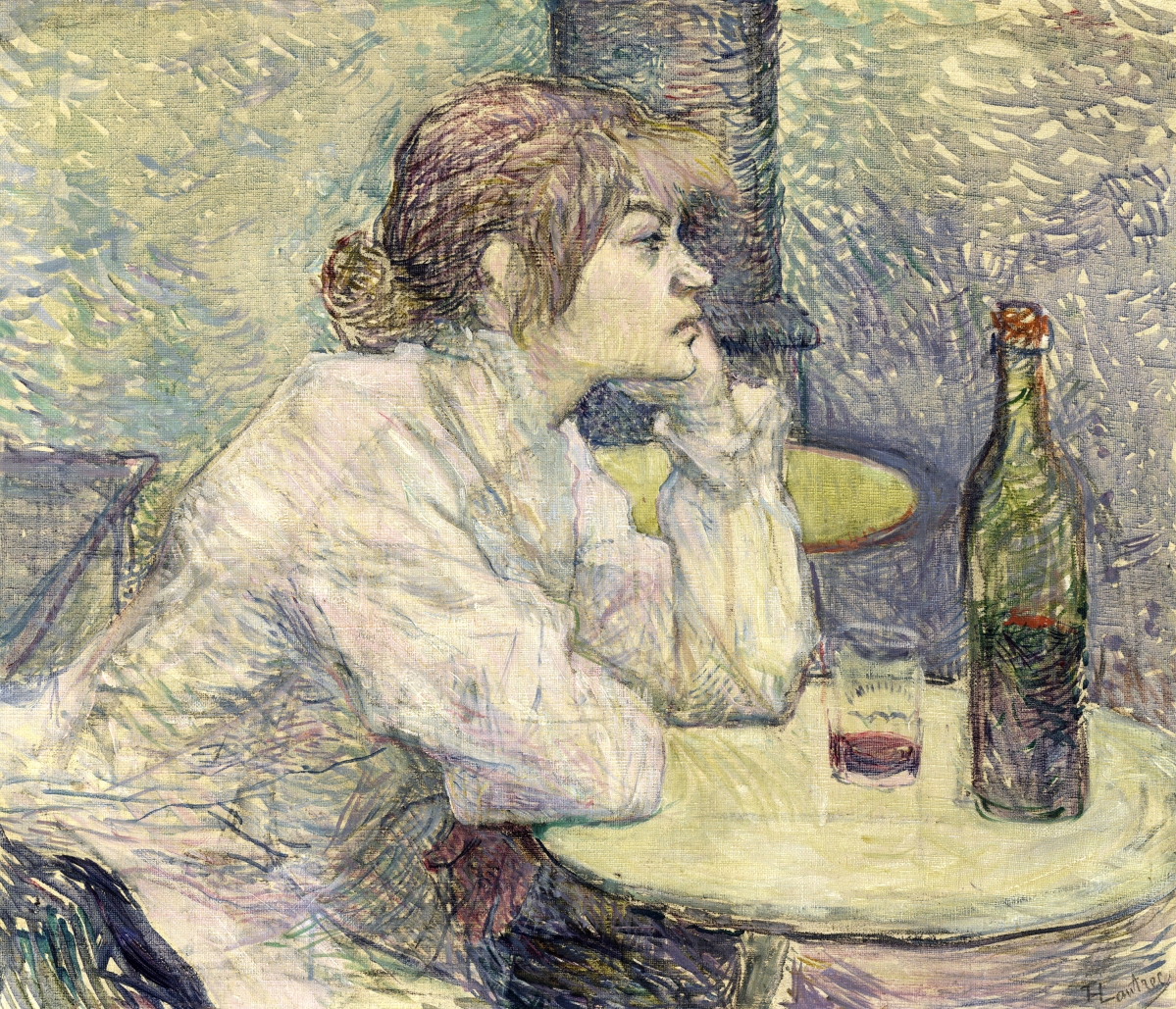

But such watering holes of the well-heeled only had so much allure for Lautrec; it seems clear from his work that he was not predisposed to a life of remote, dignified nobility. He signaled this early on with paintings like “At the Café de Mie” and “The Hangover,” both of which feature his friends in seamy cafés, posing as prostitutes (mie, crumb, is slang for prostitute) or drunkards. Their vacant affects are of a type that Lautrec was “particularly good at capturing,” says Burnham; “that kind of interiority of people” even in a public place, or onstage. She sees something similar in the central figure for his later portfolio “Elles” – an unidentified clown who is seen behind the scenes of the Moulin Rouge, her legs spread listlessly apart and her gregarious stage personality set aside for the moment.

Lautrec also defied expectations by actively pursuing advertising commissions, a form of art production that academic painters would have looked down on as purely mercenary. But Lautrec did not need the money, and he was not producing potboilers. His poster advertising a bicycle chain that could theoretically give one rider the speed of five is a case in point. His innovative use of blank paper against broad patches of ink, the sense of gesture and movement, his very modern rejection of rules of perspective and framing – all of these qualities captured the attention of consumers as well as collectors.

Posters “vied for attention” on the walls of Paris, says Burnham, and “something big and bright and different might really capture your attention and keep you thinking about it for days if not weeks to come.” For the first time, such posters became highly collectible, whether torn from the walls or ordered in pristine condition directly from the printer. This was partly because of innovations in color lithography at the time – the colors were brighter, more saturated, and more varied than ever before – but it was also because Lautrec and other artists had raised poster design to an art form.

Part of the reason Lautrec was dr awn to poster art, says Burnham, is that “he was very interested in success” – not just monetary success but also artistic success. And it is clear that success to him also included recognition for his achievements. These desires come together in his posters of the singers, actors and dancers of Paris. Through producing such work, he developed close friendships with these luminaries; he helped them to shine even brighter; and, increasingly, he became known himself, both as an important artist and as one of Paris’s utterly unique, strange and wonderful stars.

Lautrec’s very first poster was an advertisement for the Moulin Rouge, Paris’s notorious nightclub, and features one of its star performers, Louise Weber (“La Goulue,” or the glutton), doing a high kick while silhouetted, faceless spectators crowd around her. The image is unapologetically sexual, with Weber’s levitating skirts and spread-eagle pose, and the letters of the club’s name curving suggestively across her nether regions. Similar motifs are used in the poster of May Milton, who performed in a nightgown in a kind of sexy-baby routine. Here is the same little black-shod foot stomping almost audibly against the floorboards; here is the high kick and the clever use of un-inked paper to indicate lighter colors (but also, coyly, to suggest a state of deshabille, of both the performer and the paper); and here is the dynamic use of lettering to underscore the dancer’s movements. “It’s as if the type is dancing behind her,” says Burnham.

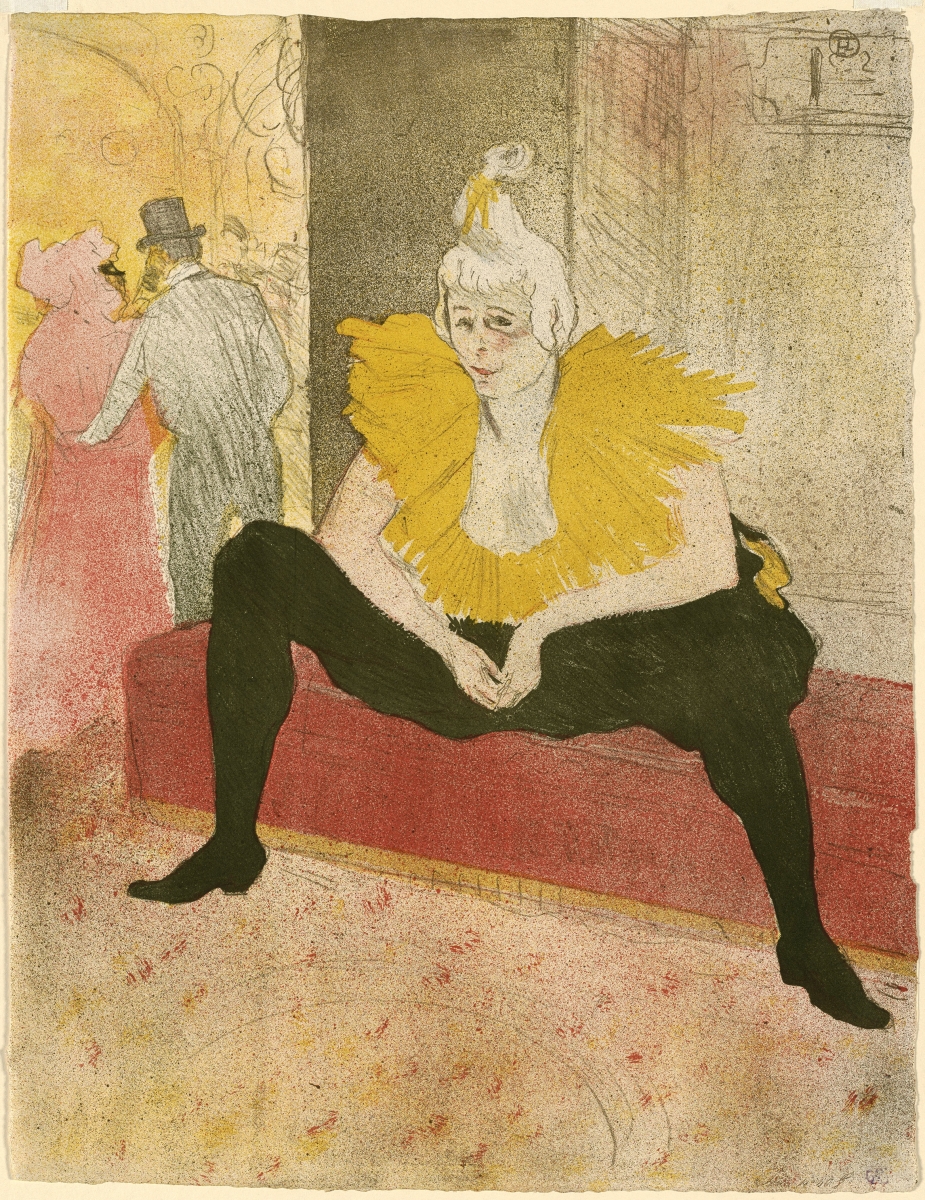

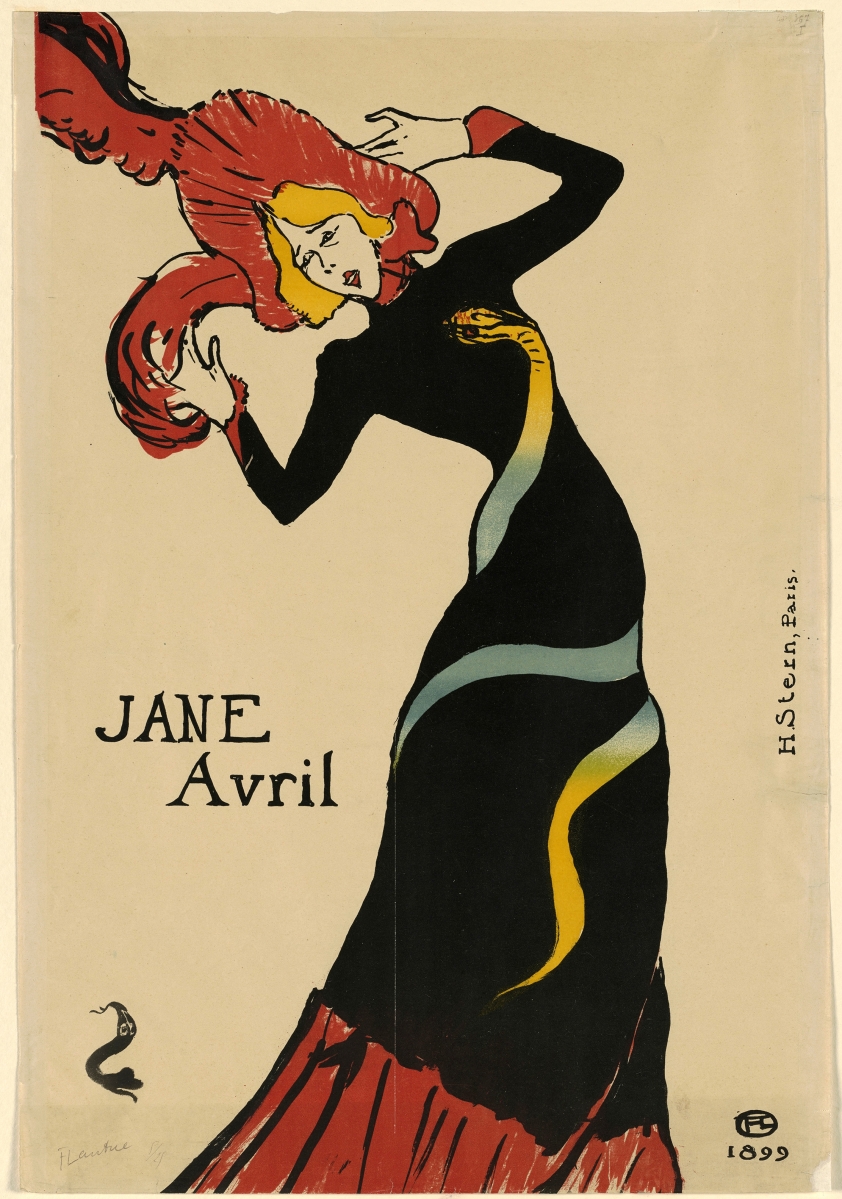

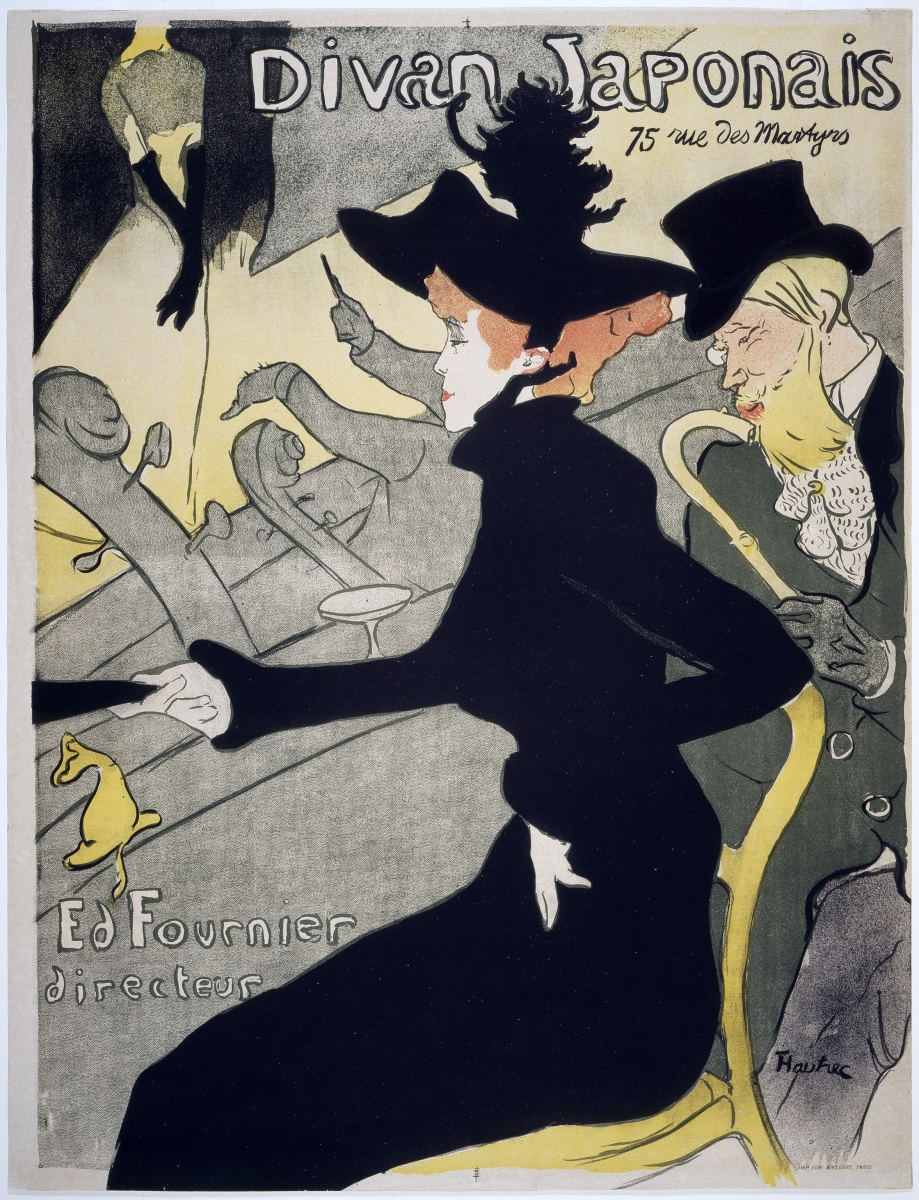

High kicks were a mainstay of dance acts in the Paris nightlife, but no high kick was as famous as that of Jane Avril, who became one of Lautrec’s closest friends as well as the most enduring stars of Paris. Avril first appears in Edgar Degas’ work, not as a performer but as a spectator: in an advertisement for the club Divan Japonais, she sits and watches from the orchestra (note the long, phallic necks of the upright basses) while a wan figure with black gloves floats across the stage. (The gloves and white dress, incidentally, identify that figure as Yvette Guilbert, another favorite and repeated subject for Lautrec). But soon Avril would be on the stage herself, as she gained fame for her distinctive dance routine. Like Lautrec, she suffered from a lifelong disability; in her case, a disease called chorea, which causes involuntary movements. Lautrec invariably portrays her contorted in some unexpected way, simultaneously graceless and riveting: her signature kick, with her arms slung around her right thigh as if it were a sandbag; a tipped-backward pose, in a black dress with a green and gold fabric snake winding from knee to bosom.

“Jane Avril” by Henri de Toulouse‑Lautrec (French, 1864–1901), 1893. Lithograph. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1932. Courtesy, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

“Everybody had a signature thing,” says Burnham, and Lautrec was “very canny in terms of how the reiteration of images, something that we know so well now…really helps to cement that idea of public image in the public’s mind.” This was perhaps more true of Aristide Bruant, the sole male performer featured in the exhibition, than any of Lautrec’s other subjects. A stocky, craggy-faced raconteur, Bruant adopted the persona of a working-class critic, famous for berating his audiences. “He really wasn’t a man of the people,” says Burnham, “but his image was so convincing, and the way he performed onstage was so insulting and vulgar, that people really believed it.” The image that he cultivated, and that Lautrec captured in his many posters of him, involved tall sewer-cleaner’s boots, a black felt hat, a dark and shapeless trench coat and a dashing red scarf. Like the riders in “The Jockey” and like Yvette Guilmont in “Divan Japonais,” Bruant is recognizable even when his face is not showing: “Bruant at the Mirliton” captures his signature look and his signature stance as he appears ready to declaim to his invisible audience.

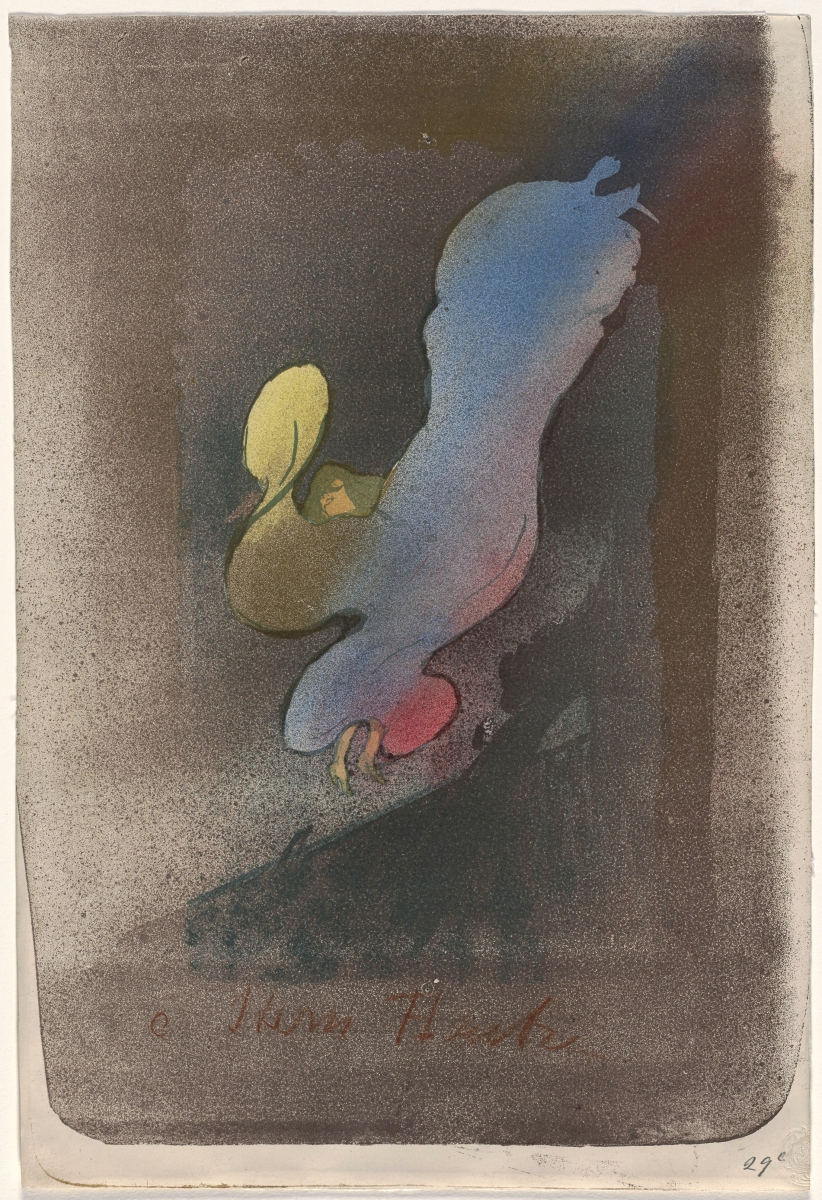

The last gallery in the exhibition is dedicated to Loïe Fuller, a Chicago-born dancer who took Paris – and the world – by storm with her innovative “Serpentine Dance.” Dressed in voluminous white robes, she held slender, concealed wands that were attached to the edges of her garment; as she swung her arms around her body, the flowing fabric followed her motions, creating illusions of flowers, birds, butterflies or even clouds. As if that were not entrancing enough, she developed a unique method of lighting her performances with colored electric lights. As she danced, the colors would change from red to blue to green and violet, creating a never-before-seen illusion that was uniquely of its time. Lautrec created a series of prints of her, all from the same plate, so they had identical compositions. But, echoing the mutability of her performances, each impression was printed in a different range of colors, some sprinkled with gold and silver dust. These delicate and light-sensitive works are rarely seen en masse, so it is well worth visiting the exhibition to see six of them all together, drawn from the collections of the MFA and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

As in so many of Lautrec’s images of celebrities, Fuller appears here less as a traditional portrait subject than as pure gesture and expression. The series “captures the freedom of Fuller’s performance,” writes Joanna Wendel in the exhibition catalog, “and perhaps reflects a longing for liberation from bodily reality in the artist himself.” This was no doubt at least as true for the disabled Lautrec as it was for anyone who saw Fuller perform – a similar feeling is engendered even today by a Lumière brothers film of one of Fuller’s many imitators, on view in the gallery. But all things considered, it may have been just as much the utter strangeness of Fuller’s dance that drew the attention of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec – that inveterate observer and lover of all things exaggerated, odd and spectacular.

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston is at 465 Huntington Avenue. For information, 617-267-9300 or www.mfa.org.