Enigmatic stone bust signed by the elusive Midcentury artist “P. Constagli,” welcoming visitors into the new gallery space of Ashville Fine Arts.

Review & Onsite Photos by Z.G. Burnett

NEW YORK CITY — Descending into the lower levels of the Manhattan Art & Antiques Center stirs an excitement of discovery, especially on Trade Days as occurred on August 3. During these events, collectors and dealers meet to trade, buy and sell their treasures in the morning and early afternoon. Dealers with spaces in the center also sometimes participate, and a feeling of general camaraderie is felt between all involved. Newcomers willing to learn are welcomed, and often offered lunch from Grand Sichuan Eastern across the street. It’s the sort of venue and event that can truly only be experienced in New York City.

It is often said of antiques shows and fairs that “you never know what you’re going to find,” and that is especially true of Trade Day. With some regular buyers and dealers, the event is a rotating cast of characters that travel in from as far as northern New England and as close as the next neighborhood. In addition to the treasure troves to be found in the center’s many shops, Trade Day goods range from ancient artifacts to contemporary costume jewelry.

Vromis Arts, New York City, showed just such variety at his table, which was laden with goods. German porcelain was placed beside Mesoamerican artifacts, Iranian metalware next to Chinese export, and so on. Some of the latest objects included a tin Coca-Cola advertising tray and a rotary wall phone. Vromis previously had a shop in the center, but now they just come in for Trade Days.

Watercolor portrait of an unidentified man, most likely by George Richmond, from Frederick “Rick” Rock of Hammond House Antiques, Eastview, N.Y.

Frederick “Rick” Rock of Hammond House Antiques, Eastview, N.Y., brought a selection of American, European and English paintings. One intriguing three-quarter painting was on the smaller side, showing a young man in the formal dress of a Scottish gentleman. In addition to his cape and black jacket, the sitter’s tartan waistcoat indicates Highland heritage. Rock believed that this was painted by George Richmond (English, 1809-1896), whose long career produced many portraits of British gentry, nobility and royalty, many of which were in this medium and size.

Lois Wagner and Beverly Sacks, both longtime New York City dealers of Nineteenth and Twentieth Century American and European Art, were sharing a couple of Trade Day tables. Wagner pointed out an oblong charcoal sketch of a woman with long, unbound hair in draped clothing, and shared that it was made by Scottish-American artist Walter Shirlaw (1838-1909). Part of the generation that largely created the American art market as we know it today but are all but forgotten, Shirlaw moved to the United States as a child and exhibited at New York City’s National Academy in 1861. At the Chicago Academy of Design, he taught a student named Frederick Stuart Church (1842-1924). Shirlaw was later a founding member of the Society of American artists and its first president.

Just as one never knows what will be seen at Trade Day, one never knows who may be there. Federico Castelluccio, known to many as “Furio” from The Sopranos (1999-2007), is an artist and art dealer as well as an actor. His paintings recall Renaissance portraiture, Baroque vanitas and still life paintings, and Eighteenth Century trompe l’oeil with surreal overtones and details from contemporary life. In 2014, he made headlines for researching and working to authenticate a previously unknown pairing of Saint Sebastian by Guercino (Italian, 1591-1666). Castelluccio shared that he is currently preparing work for an upcoming exhibition, featuring large-scale, hyper-realistic pencil sketches.

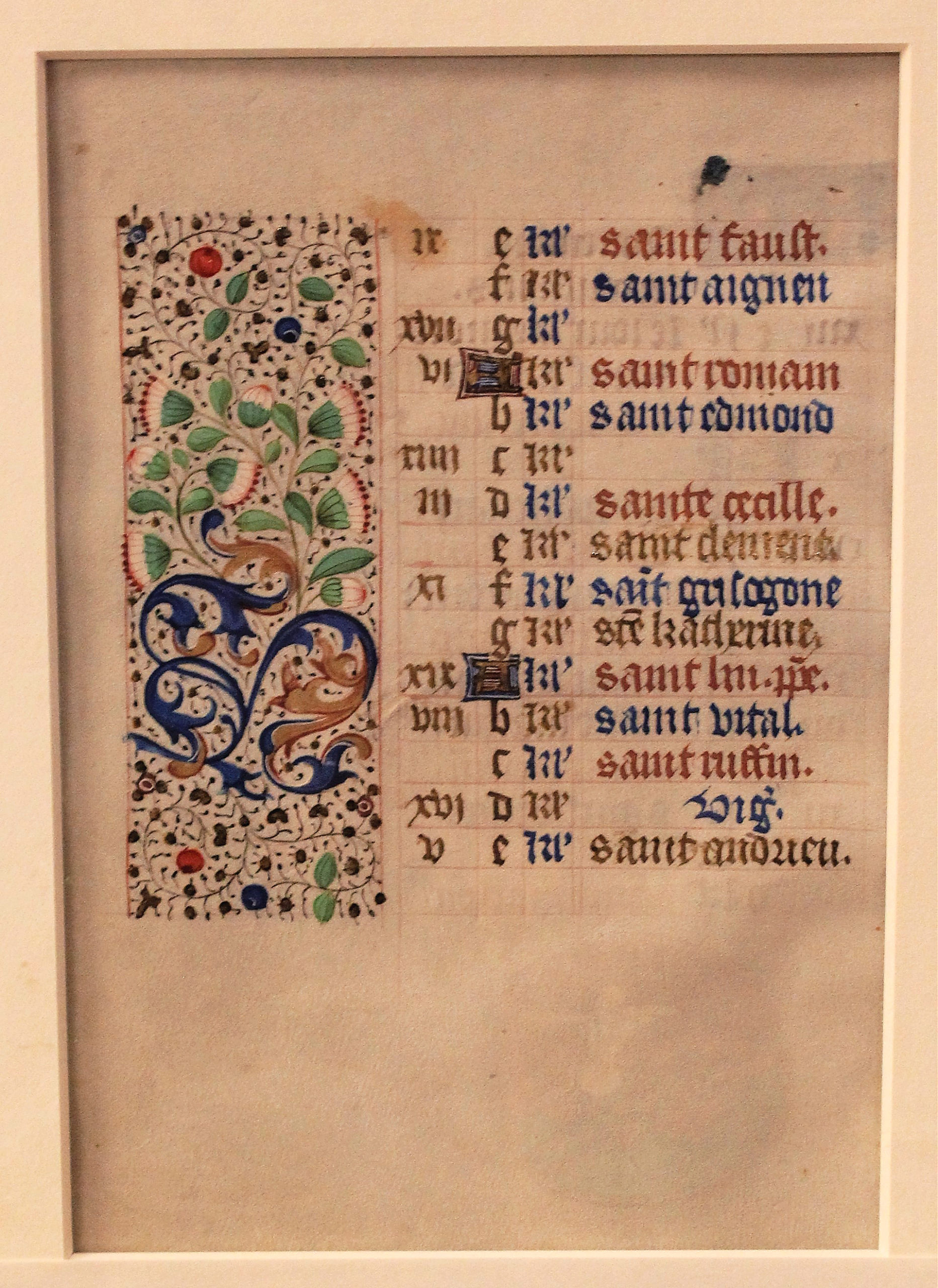

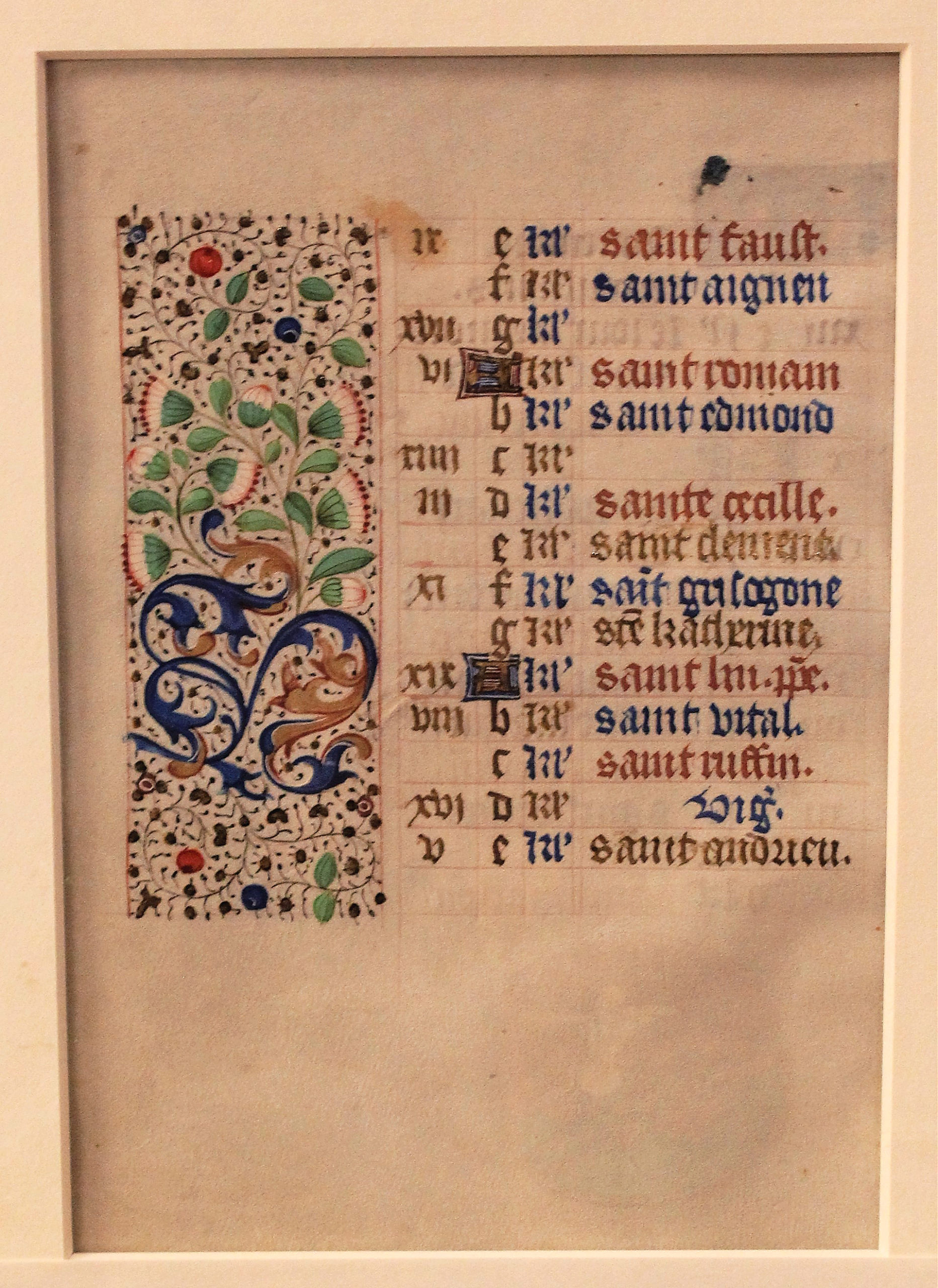

Leaf from a circa 1450 Book of Hours made in Northern France, showing the label of Charles Edwin Puckett, Akron, Ohio, and presented by Rifkin Fine Arts, New York City. The tiny strawberry in its border illumination is a “symbol of perfect righteousness.”

Presented nearby at Rifkin Fine Arts, New York City, was an assortment of majolica, antique crucifixes, porcelain and a collection of illuminated manuscript pages bearing the label of Charles Edwin Puckett, Akron, Ohio. One leaf that stood out was from a Book of Hours, made in northern France circa 1450. It was a calendar leaf, showing the month of November with feast days, names of saints that are honored on particular days and keys to finding which days are Sundays and phases of the moon. Notably, this Book of Hours was written in that era’s French and not in Latin, as this was made for personal and not clerical use.

Dennis Vestunis, Brooklyn, N.Y., brought four tables’ worth of goods to the event from a number of categories, including silver, jewelry, fine art, militaria and other antiques, under the shop name Pickpocket Antiques and Collectibles. Mounted behind a case of silverware and a mounted horn was a Qing dynasty flag dated to the late Nineteenth Century. Showing an azure dragon chasing a red, flaming pearl on a yellow field, this became the first national flag of China and is often referred to as the “Yellow Dragon Flag.” Yellow was reserved for use by imperial family members on buildings and garments at the time, and the five-toed dragon was an exclusive symbol of the emperor himself. In use until 1912, the Qing dynasty was the last imperial family to fly a flag in Chinese history. Vestunis’ flag was a simplified design that showed some fading and signs of age, but this would matter little to collectors appreciative of its bold design and historical significance.

One of the stranger objects was on the table of private collector Jan Brandt, which was covered with Asian art and artifacts of all kinds. Standing out from this group was a silver-mounted skull, which Brandt thought may have belonged to a snow leopard, which is now a threatened species due to poaching and protected by law in many countries. In addition to the brace that keeps the skull in an eternal roar, the skull shows two celestial beings on either side of its mouth and an inscription on the interior plate. This read, “To Dr M. Stepan/With the Compliments/from/of [sic] Government Mental Hospital/Thailand.” The commemorative skull was undated, but the font seemed to be from the early Twentieth Century.

Commemorative snow leopard skull, inscribed with honors from Thailand’s government mental hospital, was offered for sale or trade by private collector Jan Brandt.

Michael Szarvasy works with David Ashville of Ashville Fine Arts, and had a table set up right in front of their gallery with Asian, African and European items. Szarvasy was born in Hungary but has lived in New York City for most of his life, and was excited to share that he and Ashville would be expanding their business to a second space across the hallway. The new gallery was still being installed but a few objects were already in place, including a Midcentury Modern bust of a woman with a head scarf, signed by “P. Costagli.” Not to be confused with the jewelry designer Paolo Costagli, this artist’s signature has appeared on only a few sculptures to appear on the secondary market.

The Manhattan Art & Antiques Center is at 1050 2nd Avenue. For more information, www.the-maac.com or 212-355-4400.