This cobalt-painted chandelier centered its crystal peers in the window of Hadassa Antiques Gallery.

Review & Onsite Photos by Z.G. Burnett

NEW YORK CITY – The Manhattan Art & Antiques Center (MAAC) is a multi-floor maze, displaying treasures of every kind behind the glass windows of each shop. For those lost among the sparse, minimalist styling of contemporary galleries, MAAC is a sanctuary. Seemingly out of time, the gallery is a celebration of maximalism with gilt, crystal, metalwork and fine art layered behind each gallery’s windowpanes. Some shops’ stock even overflows, perpetually arranged outside of their doors. Even comparatively lesser stocked shops still present hundreds if not thousands of years of material culture from across the globe. Not all of the shops were open on Trade Day, which took place on Thursday, November 3, but those that participated opened the doors to their troves for those who came searching.

Trade Day is a regular tradition at MAAC, inviting the public once a month to bring goods worth at least $1,000 for bartering with dealers and other collectors who set up tables in the hallways. “The best part [about Trade Day] is that nothing costs anything,” said Alexander Acevedo, a dealer who has been in the business for 66 years. For Trade Day, Acevedo was assisting with the event, catching up with colleagues and coordinating the feast provided by Grand Sichuan Eastern across the street.

As with all art and antiques shows, MAAC’s dealers and patrons are as varied a cast of characters as the wares to which they have devoted their lives. Chief among these is Chen Shizhen of the Ton Ying Company on the second concourse, a corner gallery overflowing with art and artifacts from Chinese history. Chen, 86, has been dealing in MAAC for 47 years and adds his own remarkable life story to that of the Ton Ying Company, one of the first Chinese art and antiques dealerships in New York. Founded by Zhang Jingjiang, the company was formerly located across from Tiffany & Co. on East 57th Street and welcomed customers such as John D. Rockefeller III, who was an almost-weekly patron of what he would call his “Chinese toys.” Many private and public American collections of Asian art were built from Ton Ying, including that of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Chen never met Zhang, but continues the business and “the memory [of the company] even in a small way.”

Unique among the antiques shops was Illisa’s Vintage Lingerie, specializing in unmentionables from the Nineteenth Century up to the 1950s; these embroidered mules in her window were priced at $385.

Chen was born in Shanghai and attended La Salle College in Hong Kong, later joining his elder sister in the United States and graduating from Arizona State University with a degree in physics. He moved to New York in 1963 to research astronomy at Columbia University and began working for Ton Ying part-time. When the company struggled following the death of Zhang’s successor, Chen’s uncle bought a sizeable part of its stock at auction that now populates the shelves of his MAAC gallery. In addition to dedicating his own business to Ton Ying, Chen actively researches and collects past archives of the company’s listings. These prices are in two or three-digit numbers from sales made when Chen’s apartment near Columbia cost $50 a month, a price comparable to that of a vase made by a master craftsman at the royal Jingdezhen kiln in the Jiangxi province. Though sales of Asian art have skyrocketed over the past decades, Chen has no intention of participating in online auctions. “Buying an antique is a touch-feel business,” he says.

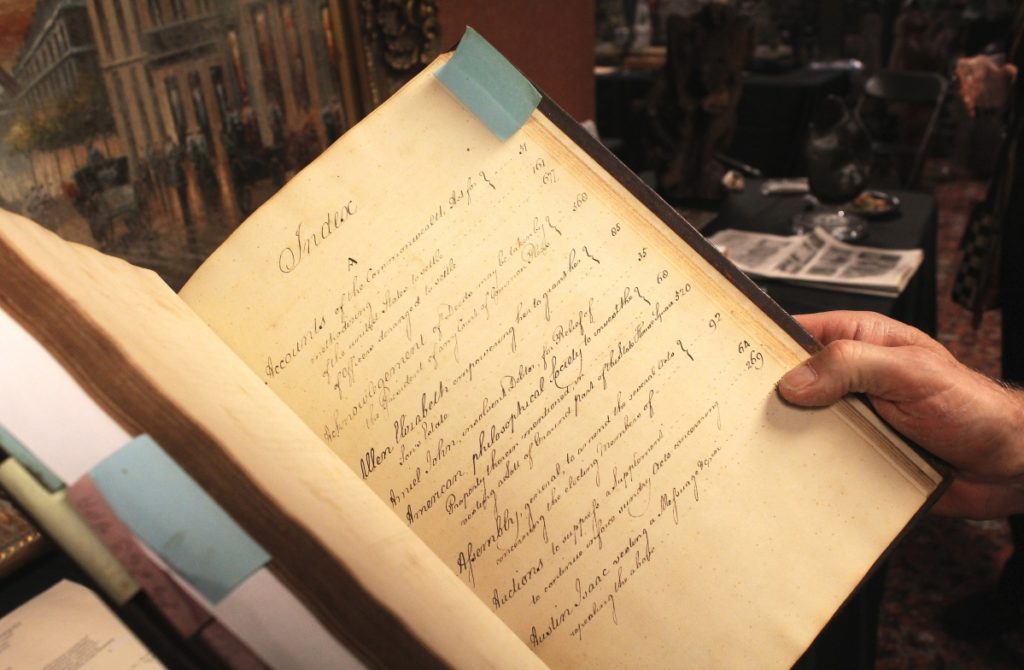

John N. Tkachuk of Ava, N.Y., created his own sales space in one of the venues nooks, setting up tables with American art and artifacts. Founder of JT Productions, Tkachuk is a researcher and archivist who specializes in colonial history and the Revolutionary War. Spread across his table were documents associated with Samuel Powel (1738-1793), mayor of Philadelphia (1775-76, 1789-90) and member of the Pennsylvania State Senate (1790-93). Tkachuk bought the archive at the Park Avenue Armory Show with a full provenance on the objects, which included a 1742 property deed on vellum signed by Powel’s father who built 90 homes in Philadelphia during this time, and a book of Pennsylvania laws that once belonged to Powel. Titled Laws Enacted in the General Assembly of the Representatives of the Freemen of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, this second volume covered the sixth to ninth general assemblies from 1781-85. In addition to the numerous annotations in the book’s margins, Powel wrote a 15-page index of its contents from his own experiences in Philadelphia politics. Powel’s home is now a museum run by the Philadelphia Society for the Presentation of Landmarks, with its rear parlor now part of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s collection and its ballroom in the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

John N. Tkachuk of JT Productions (Ava, N.Y.) brought an archive of documents related to Pennsylvania senator Samuel Powel (1738-1793), including Volume Two of Laws of Pennsylvania with a handwritten Index.

One of the largest tables laden with portraits and fine art was outside of Solomon Treasure, a multi-generational gallery of important European and American antiques and art. One of the rarest objects was an original watercolor by Louis Comfort Tiffany, signed in pencil and stamped on the verso, showing a design for the similarly scarce Tiffany & Co.’s Water Lily leaded glass lamp shade. The gallery’s interior was an extravagant salon of fine furniture and decorative arts, some with price tags in the area of $1 million. Michael Solomon works in the gallery with his brother Mory and father Rubin, the third and fourth generations of the family business. We were surprised to learn that Solomon returned to MAAC from Los Angeles just eight weeks earlier, where they moved after more than 35 years of dealing in New York beforehand. “We just wanted a fresh start,” Michael said.

Many of MAAC’s dealers formerly had their own store front but have found a new community of dealers and customers in the historic antiques center. Paul J. Bosco has been selling coins and medals since 1973; he sold in the MAAC in the 1990s until opening his own shop on Madison Avenue, then returned to his current location at MAAC in 2018. Aside from his focus on numismatics, Bosco’s shop displayed objects from rare books to Asian Art to early Twentieth Century cast iron scale models of skyscrapers. While talking with us, Bosco was balancing on a ladder to untie a collection of African ritual phallic covers made from hollowed gourds, representing and inviting fertility. These were traded with a small yam mask from Papua New Guinea, made by the Abelam people. Even with all these layers of history for sale, Bosco said that the trade was “stronger pre-Covid, like everything,” but was coming back around. “It all does, eventually,” he commented. Bosco, and all the other dealers of MAAC, will continue to trade and sell until “it” does.

The Manhattan Art & Antiques Center is at 1050 Second Avenue and 56th Street. The next Trade Days will be December 1 and January 5. For more information, www.the-maac.com or 212-355-4400.