Seven years before Tristram Hunt became director of the Victoria & Albert Museum, he was a Labour Party politician that just earned a seat as a member of Parliament for Stoke-on-Trent Central, the same territory that was popularly lorded over in the Eighteenth Century by the English potter Josiah Wedgwood. It was one year after the famed pottery had gone into receivership and his constituents were concerned – not only for their livelihoods but for the 80,000 artifacts in the Wedgwood Museum that documented this city’s major contribution to the world. In 2014, the Wedgwood Museum and its contents were purchased by a consortium of organizations and donated to the Victoria & Albert Museum, which Hunt would come to lead three years later. The director pays homage to Stoke-On-Trent’s great forefather in his latest title, The Radical Potter: The Life And Times Of Josiah Wedgwood, available from Metropolitan Books. We sat down with Hunt to talk reverence.

Is Josiah Wedgwood the most notable potter in English history?

Yes, he is. Obviously there are different media, he’s not a studio potter, but in terms of the father of English pottery, it’s Wedgwood.

When does the director of the V&A find time to write a book?

I managed to find time to write during lockdown. This book had been under research since late 2015 or 2016, but I could never find time to get down and do it. The end of commuting and evening receptions meant I finally found some time to muscle down and get it done.

Why was Wedgwood a radical?

He transformed the pottery industry – he was a radical in production, with new material like jasper, with the creamware that became this phenomenal global alternative to porcelain, with distribution and his use of canals. He was also a political radical – he campaigned for democracy, he supported the Colonists, he was excited by the French Revolution and the rights of man, and he was a proponent of the abolition of slavery. He was a patriot but fought for radical reform when necessary.

Would he fit in with the politics of artists today?

Interestingly, he always had a troubled relationship with artists themselves. As a businessman and designer, he found them difficult to manage. He had great support from the aristocracy, the Queen and King of England, the Empress of Russia, and yet at the same time, he was radical in his ceramics, whether it was making teapots supporting John Wilkes and the campaign for democracy, or the antislavery medallion – that was using design for change. He was both this very astute businessman but also this nonconformist radical figure at the same time.

Did his abolitionist stance put him at odds with the wealthy?

No, he tailored his messages for different audiences. He made sure that he was looking after his patrons very successfully even as he was writing these private letters that supported giving more people the right to vote. So he managed to separate these viewpoints.

Did he consider himself a potter for the rich or the common man?

He thought that he was a potter, which allowed not the common man, but the middling sort, the middling classes, to have access to the taste and productivity of the upper classes. He always began at the top of the tree with what he called the “legislators in taste,” the great influencers in fashion, and he would capture their imagination. And then because he transformed mass production, he could grow a much broader market for consumers. His brilliance was to give an air of exclusivity to a mass market product.

The Radical Potter: The Life And Times Of Josiah Wedgwood is available from Metropolitan Books.

What kind of social endeavors did he champion?

He was a tough boss, a tough employer, and he had faced down demands for wage rises, but he cared a lot about the health and safety for his employees. He worked to alleviate lead poisoning. When he rebuilt his factory, he built homes for his workers. His greatest issue was his campaign to abolish the slave trade. When it came to the American Revolution or changes to Parliament, he wasn’t overtly public about that. With the campaign for abolition, he was very vocal.

Did he have an overarching idea behind that?

It was born of this patriotism, that not only was there raw inhumanity and evilness in the enslavement, degradation and murder of enslaved Africans, there was an idea that Britain was letting itself down. The idea of Britain as an island of liberty, rule of law, civilization and improvement, that being involved in this disgusting trade was undermining the meaning of the nation. It wasn’t born of a sense of racial equality, it was as much about protecting the identity of Britain.

How should we consider Wedgwood the man?

He was a figure of the enlightenment. This individual whose intellectual range and vision was awe inspiring, and at the same time this loving father and gregarious character. He consumes people and ideas with this incredible energy ranging across so many disciplines and subjects. You look back at him as this physical giant, even though he suffered from having his leg amputated.

How does a potter become among the wealthiest entrepreneurs of the Eighteenth Century?

It’s the sales and marketing brilliance. In a growing market of consumption, he repeatedly surfed the wave. His other brilliance is driving down production costs and creating phenomenal efficiencies in production and distribution, and then having a great eye for marketing and retail. Introducing an incredible transparency in costs, new systems of accounting, new systems of transport and production. He’s working at both ends and that’s part of the key to his success.

Did any of his workers ever push back against his efficiencies?

Yes, what he did was very conscious. He wanted “to make such machines of the Men as cannot err.” His goal was to dehumanize the production process. This was the contrast as Wedgwood the great designer and creative, when it came to the manufacture of his good, he was involved in a process of deskilling. He didn’t want creative flair among his workers. He wanted them to follow a strict production line and there was hostility among the workers who didn’t like the new systems of working, systems that were more mechanical and uniform. You see in his letters a resistance to that. But he’s not eliminating positions, he’s growing. He introduces middle management, the overseers, that’s a new part of it.

What about marketing?

He introduced the back stamp – the brand embedded into the ware as a symbol of quality. He made limited edition designs, he has influencers who supported the product and new models of advertising. He’s very good at naming – when the Queen of England likes his creamware, the name goes from creamware to Queensware. He has a good feel for the psychology of the consumer, he was one of those people who could convince people they needed something they didn’t know existed.

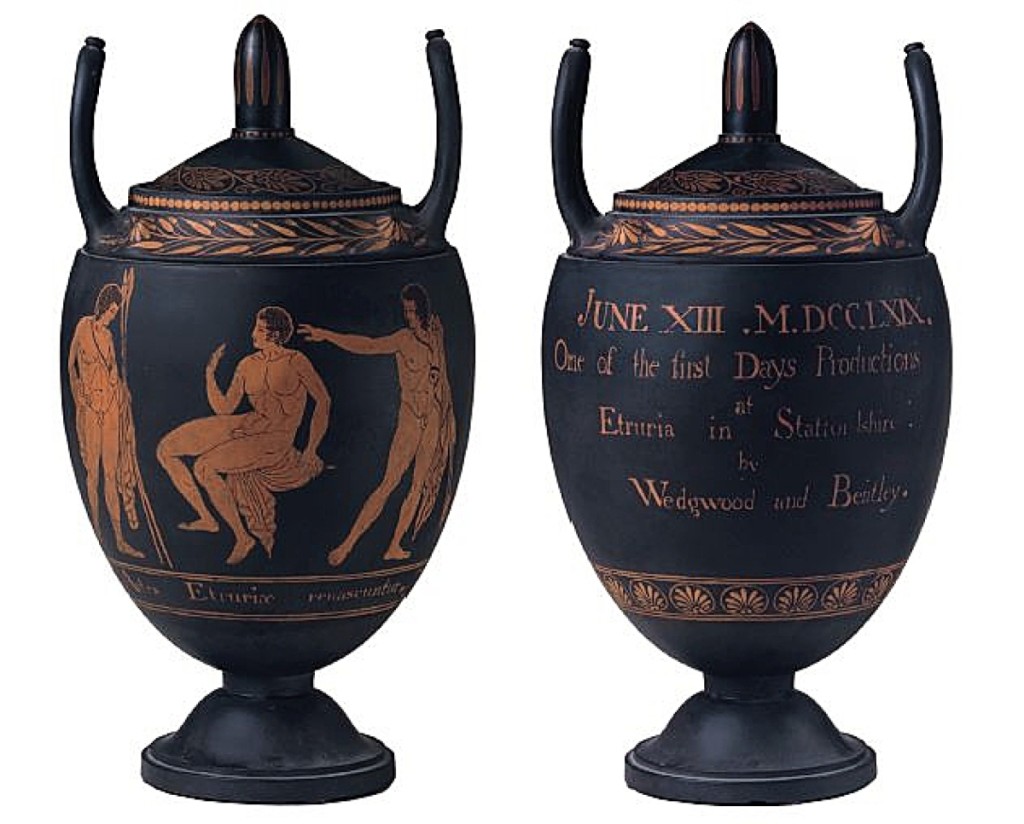

A ‘first day’ vase: black basalt painted in encaustic colours, by Josiah Wedgwood, 1769. Copyright © Victoria & Albert Museum, London

What historical documents have you used as the basis for your research?

The archives at the Wedgwood collection – in there are all the letters from Josiah Wedgwood to Thomas Bentley and his children and others. They’re also published in volumes, but there are some not there. He has these wonderful notebooks full of his jottings about horses or landscapes or coal types and clay types. Very idiosyncratic jottings on history. Also his pattern books, he was like a designer: always busy, always drawing, lots of pictures. He had a feverishly busy pen.

Was he stylistically influenced by other artists?

He has this great change in his aesthetic when he moves from Rococo and Baroque designs into Neoclassicism. It wasn’t really artists that inspired him, it’s the rediscovery of the past, the grand tours around Europe, the digs at Pompeii. All of the classical designs that are being unearthed through the archeological digs inspired him, he draws very heavily from new literary accounts of great classical works of the past. It inspires the vases and so much of his aesthetic in the 1770s.

How far does his influence go?

His creamware becomes imitated right around Europe – not as a great artistic product, but as tableware, it becomes a form of ceramics. His business partner Thomas Bentley goes to Paris and sees all the shops there selling English earthenware, which he is delighted by. And obviously Jasper, this new ceramic material, which designers today toy with and think about. The Queensware and the Jasper had a global impact.

Did the new materials expand his markets?

Right from the earliest days he had very strong exports to America: Boston, New York, etc. The ware comes out of Stoke-on-Trent, up the canals to the Liverpool docks and across the Atlantic from there. So he has markets in the eastern seaboard of the United States, the Caribbean and the British plantations, strong markets in Europe as well – Germany, France – and big export markets in Russia. At one point he tries to break into Turkey, he was always interested in new markets.

What about China?

This is the great challenge – in 1792, there’s the first British embassy in China. The ambassador takes with him six Wedgwood vases to demonstrate to the emperor how sophisticated British pottery is. You have this extraordinary scene that the British are trying to teach China about china. Wedgwood had this dream to conquer China, but it never materialized.

Oval medallion of white jasper with a black relief of a chained Black enslaved man in a half-kneeling posture facing right, modelled by William Hackwood, made by Josiah Wedgwood and Sons, c.1787. Copyright © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

What did the Chinese think about his material?

The official accounts are that the emperor was contemptuous. Yet the truth was that this is the pivot point, the moment, because of the Industrial Revolution, that the west is going to take over the east in terms of prosperity and wealth. Even though the Chinese refused, the western world is now in the Great Divergence, the moment when Europe and the Atlantic world is going to overtake India and China, which lasts a good two centuries.

How many pieces of Wedgwood are in the V&A?

The V&A now looks after the Wedgwood collection, there are 80,000 pieces in that. And we probably have another 1,000 in South Kensington. The Wedgwood collection came to us in 2014 when we saved the museum from being sold off. To prevent it from ever happening again, it came under the umbrella of the V&A and became part of the national collection.

Any research discoveries in the book?

It was more of a contextualization of the work. The main scholarly contribution is a proper account of his political philosophy – his account of radical patriotism in context and looking at the sources of his political contributions. People never really connected that to his pottery. And then the epilogue, which is the account of the end of the business, the first account of why it failed as a business in the last 25 years. It collapsed in 2009 and then it was taken over in 2010 and the new owners of the business refused to honor the pension deficit or help save the museum. To my mind they were not worthy of the name of the business. They had no feel for the business and they stripped it all down. The usual story. Everything Wedgwood said was important – quality of production, brand strength, authenticity, investing in design – all of those components were absent.

Do you remember first learning about Wedgwood?

In British schools, you learn a bit about him as part of the Industrial Revolution. I was a member of parliament for Stoke-on-Trent from 2010 to 2017. It’s really only being in Stoke and understanding it and meeting the workers who used to work at the company and their reflections about that business, that I came to really understand Wedgwood and his importance in North Staffordshire and Stoke-on-Trent. He’s a kind of founding figure in that community.

Is the V&A doing anything with Wedgwood for this occasion?

We’re activating new displays in the museum, which is just outside Stoke-on-Trent. We have a big display on the anti-slavery medallion and working with students to take them back to the designs of the 1780s. In time, we want to put together a great traveling Wedgwood exhibition, the very best of Wedgwood. It’s long overdue in my mind.

-Greg Smith