“Cologne, the Arrival of a Packet-Boat: Evening,” exhibited 1826, oil on canvas, 66-3/8 by 88¼ inches. The Frick Collection, New York. —Michael Bodycomb photo

By James D. Balestrieri

NEW YORK CITY – It is easy to get lost in Turner. Lost in his dazzling light, his palette, lost in the serenity of his scenography – which makes it hard to write about him, to get that scholarly distance, that necessary, critical detachment. To think about Turner, to write about Turner, you have to look away from Turner.

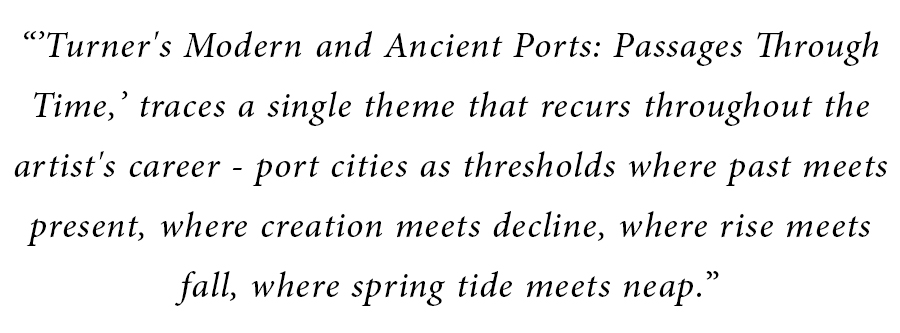

In defiance of the sheer beauty that Turner seemed to be able to summon at will, the Frick Collection’s new exhibition, “Turner’s Modern and Ancient Ports: Passages Through Time,” traces a single theme that recurs throughout the artist’s career – port cities as thresholds where past meets present, where creation meets decline, where rise meets fall, where spring tide meets neap.

History – and, therefore, time – as cyclical was not a new idea in the late Eighteenth and early Nineteenth Centuries, but world events and historiography were running parallel courses at the time. In an era of revolutions – American and French – the idea of rise and fall eternally alternating dominated Atlantic culture. Edward Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, spanning the earliest formation of the republic to the fall of Constantinople, stood as a cautionary tale for all empires and the hubris that inevitably accompanies them. The Italian philosopher Giambattista Vico described civilizations going through an organic cycle – ages dominated by concepts of divinity, then by heroic, godlike humans, then by human laws, then, at last decaying into class conflict. Hegel follows on from this, as does Marx, Nietzsche, Spengler and many others. The notion of rise and fall, of thesis/antithesis/synthesis, would permeate Romantic and Modernist thought – and art. The cycle would challenge the arrow of biblical eschatology. Above all, the example of Napoleon’s imperial succession to the French Revolution and its republic, of his meteoric rise and ultimate fall in 1815, would stand as a living example of what Gibbon had written and of Vico’s cautionary tale shadowing every triumph.

To understand how this dynamic operates in Turner’s port scenes, it is best to begin with the ancient ports. Turner often painted these works in pairs, and the excellent exhibition catalog delves deeply into diptychs depicting, as an example, the founding and fall of Carthage. Fortunately, the exhibition itself features two outstanding ancient port paintings: “Ancient Italy – Ovid Banished from Rome,” exhibited in 1838, and “Regulus,” exhibited in 1828, then reworked and exhibited again in 1837.

To understand how this dynamic operates in Turner’s port scenes, it is best to begin with the ancient ports. Turner often painted these works in pairs, and the excellent exhibition catalog delves deeply into diptychs depicting, as an example, the founding and fall of Carthage. Fortunately, the exhibition itself features two outstanding ancient port paintings: “Ancient Italy – Ovid Banished from Rome,” exhibited in 1838, and “Regulus,” exhibited in 1828, then reworked and exhibited again in 1837.

Two things are immediately apparent to us (and they would have been equally apparent to Turner’s contemporaries) as we stand in front of “Ancient Italy – Ovid Banished from Rome.” The first is the blinding sun, reflected in the calm water and the haze it casts over the scene. The second is our point of view, the distance between us and the various groupings of people in the work. In fact, the people are small, verging on indistinct.

It is tempting, given the title and subject of the work, the forced exile of one of Rome’s greatest poets after an unspecified indiscretion – whether through some satirical portrayal of power or some personal slight – by the Emperor Augustus, to see the figure being led away at left as Ovid, and the belongings strewn on the bank as his, but Turner knew the various versions of the story and in all of them, Ovid was given time to leave and was never deprived of his possessions. Perhaps, as Johanna Sheers Seidenstein writes in her catalog essay, “Inglorious Histories: Turner’s Ancient Ports,” this scene within the scene may constitute “an exteriorization of the internal, emotional experience of exile, which, even if gently enforced, was, for Ovid, a punishment as harsh as death.”

This “exteriorization,” a naturalism of a sort, is characteristic of the ancient as well as the modern port paintings. Yet it is an extension of naturalism, for not only does the landscape and weather symbolize an internal state (think of Ibsen’s plays); human beings and their productions – architecture in particular – become symbolic as well. A tomb with Ovid’s name on it appears at lower left, while the temples of Rome, idealized by the artist, stand in mute judgment. At right, the figures, a woman bent in mourning, a figure with her arm around another’s shoulder, a pair of lovers seem both to witness and ignore the scene and to stand for the constant themes in Ovid’s poems: sadness in the Tristia, the emotions of mythological women as they write to their heroic husbands and lovers in the Heroides, love itself in all its guises in Amores, Ars Amatoria, Metamorphoses.

“Harbor of Dieppe: Changement de Domicile,” exhibited 1825, but subsequently dated 1826, oil on canvas, 68-3/8 by 88¾ inches. The Frick Collection, New York. —Michael Bodycomb photo

“Regulus” illuminates the story of the Third Century BCE Roman general, captured by the Carthaginians, who was sent to Rome to negotiate a treaty but was forced to promise to return to Carthage if he were unsuccessful and face torture and death. Regulus exhorted the Roman Senate to refuse the terms of the treaty and returned to face his horrid doom despite the protestations of his family, friends and colleagues. Back in Carthage, his eyelids cut off by his captors, he faced the sun until he went blind, then was executed. In Turner’s composition – one of many treatments of the subject – Regulus may not even appear, though some accounts say he is he is a tiny figure in white, a minuscule brushstroke of paint, on the steps at right.

Instead, other figures in the foreground at left and right embody the pull of heroism and the longing for family, but the turgid water and the blinding sun put us in the position of this paragon of classical virtue. We feel churned up, conflicted, blinded, as Turner himself must have on the many occasions when he pitted his poetic visions against the neoclassical history paintings of Benjamin West and many others, friezes of figures enacting the most dramatic moments from history, religion, myth. For us, accustomed to Modernism, post-Modernism, Pop art, Outsider art, installation and performance art, the beauty in Turner seems almost quaint. But in its own day, in Turner’s own time, Turner’s light was as blindingly radical as van Gogh’s. Perhaps he, too, felt blinded by his own vision, felt exiled because of it.

Perhaps the shimmering palaces he painted, the Ozymandias ephemerality of their grandeur – to borrow from Shelley’s poem – gave him comfort, that the past shall pass, that the mighty shall fall, that his art, too, shall have its day in the sun.

The centerpieces of the exhibition are two depictions of modern ports from the Frick’s own collection, “Harbor of Dieppe: Changement de Domicile,” exhibited in 1825, and “Cologne, the Arrival of a Packet-Boat: Evening,” exhibited the following year.

One of the unintended consequences of Napoleon’s legacy was a network of good roads he had built to move his armies. This grand infrastructure project paved the way for a flood of middle-class tourists from Britain and elsewhere in Europe. The Grand Tour, or Bildung – education through travel – became a staple trope in literature, music and art. Publishers found ready markets for folios of “picturesque views,” and artists like Turner seized at the opportunity to extend their fame and make some extra money.

“Cologne from the River,” 1820, watercolor on paper, 12-1/8 by 18¼ inches. Seattle Art Museum, gift of Mr and Mrs Louis Brechemin. —Paul Macapia photo

While the scenes of Dieppe and Cologne were not done for a folio, they are related to the many watercolors of ports of Great Britain and the English Channel he executed for such publications. As such, these major paintings share a documentary sensibility with the watercolors. Like the paintings of ancient ports, Turner’s Dieppe and Cologne seem to have a story – or stories – to tell, but, detached from the life of Ovid or the tale of Regulus, these stories are even more deeply coded, ambivalent and ambiguous.

Ports, in these works, are edges, frontiers whose tides are mirrored in the constant flow of people, information, history. Ports are connections to the larger world. Concentrations of human endeavor that are constantly being constructed and reconstructed, razed and remade. Classes collide here. Ancient occupations, such as fishing and trading, collide with new worlds of commerce and tourism. Instead of pendant paintings, Turner encapsulates opposites within single canvases, but as with the ancient port paintings, the signifiers lie in the details and in their relationships to one another.

The old fishing town, Le Pollet, appears on the far left of “Harbor of Dieppe: Changement de Domicile,” while the city of Dieppe, rebuilt after having been leveled in an Anglo-Dutch bombardment in 1694, dominates the right side of the canvas. The River Arques divides the work. Ships, smaller boats, crafts of every kind, a veritable forest of masts fill the scene, obscuring the way to the sea in a narrow shaft of light left of center. Turner includes many of the landmark churches and buildings in the town, but the action at right, a market of some kind, attracts our attention, as well as the attention of the figures on the boats at left.

We zero in on a couple unloading a boat filled with luxury goods – the occasion for the subtitle, “Changement de Domicile,” perhaps? Perhaps. In her catalog essay, “Liminal Spaces: Turner’s Paintings of Dieppe and Cologne,” Susan Grace Galassi articulates the ambiguity in this part of the painting: “Objects such as the gold-framed pictures are not likely to have belonged to the fisherman and his wife. Are they helping with a move for a middle-class Dieppois couple, or, as the jumbled appearance of the objects would suggest, conveying used goods to market?”

“Cologne, the Arrival of a Packet-Boat: Evening” poses even more distinct pairs of opposites, using the water to divide and connect them. While at right, women in local costume stack lumber and pile hay into breaches in the old medieval walls, a ferry of travelers, or, perhaps day-tripping burghers, gawks and makes merry. Again at left, the new bridge in the distance contrasts with the tower of the Twelfth Century Gross St Martin church at right. An arachnid of twisted fishing gear sits in the water, dominating the foreground, suggesting, as contemporary guidebooks stated, that Cologne was “best experienced from the outside.” To reinforce this notion, a dog laps at the water right beside a pipe discharging effluent.

“Ancient Italy — Ovid Banished from Rome,” exhibited 1838, oil on canvas, 37¼ by 49-3/16 inches. Private collection. ©The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Art Resource, NY

What lingers, for me at least, in Turner’s port paintings, is a feeling echoed famously in W.H. Auden’s ekphrastic poem “Musee des Beaux Arts” inspired by Pieter Brueghel’s painting, “The Fall of Icarus,” a feeling that labor, work, life, love, all go on even during the most momentous events, and that, conversely, art sees, even in seemingly ordinary moments, signs of wonder that might otherwise go unnoticed. I’ll leave you with Auden:

In Breughel’s Icarus, for instance: how everything turns away

Quite leisurely from the disaster; the ploughman may

Have heard the splash, the forsaken cry,

But for him it was not an important failure; the sun shone

As it had to on the white legs disappearing into the green

Water, and the expensive delicate ship that must have seen

Something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky,

Had somewhere to get to and sailed calmly on.

“Turner’s Modern and Ancient Ports: Passages through Time” remains on view until May 14. The catalog that accompanies the exhibition contains essays by Susan Grace Galassi, Ian Warrell, and Joanna Sheers Seidenstein, with Gillian Forrester, Rebecca Hellen and Eloise Owens. Published by the Frick Collection in association with Yale University Press, New Haven and London, the 176-page volume has 120 color illustrations and is available in the museum shop for $25.

The Frick Collection is at 1 East 70th Street. For information, www.frick.org or 212-288-0700.

Jim Balestrieri is the director of J.N. Bartfield Galleries in New York City. A playwright and author, he writes frequently about the arts.