“Canoe in Rapids,” by Winslow Homer, 1897. Watercolor and graphite on off-white wove paper. Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Louise E. Bettens Fund. Photo Harvard Art Museums; ©President and Fellows of Harvard College. — On view at The Harvard Art Museums, “Winslow Homer: Eyewitness.”

By Jessica Skwire Routhier

GLOUCESTER & CAMBRIDGE, MASS. – If it’s summer in New England, odds are there is a Winslow Homer show to see. So closely has Homer come to be associated with the rocky northern Atlantic coast that, for many, the experience of the landscape itself is incomplete without also experiencing Homer’s depictions of it, well-represented in the region’s museums. But Homer was a marine painter long before he began to produce his iconic seascapes of Maine, where he kept a studio after 1883, and he had a whole career as an artist before he ever began to paint the sea.

Two exhibitions this season offer a deep look – with some surprises – into the early career of this defining American artist. “Winslow Homer: Eyewitness,” at Harvard Art Museums through January 5, examines how his experience as a Civil War correspondent affected his later work; and “Winslow Homer at the Beach,” at the Cape Ann Museum through December 1, focuses on a key decade in his development as a marine painter.

There is significant local interest in the latter story, since some of Homer’s earliest seascape paintings were done on Cape Ann itself, a peninsula that juts out to sea a few dozen miles north of Boston. Though often overshadowed by the better-known Cape to the south, Cape Ann, too, was an increasingly popular vacation spot in the 1870s and – equally important for Homer’s sensibilities – home base for New England’s biggest fishing fleet, out of Gloucester.

Homer’s Gloucester seascapes from the mid-1870s through 1880 are well-known and much studied; however, the present exhibition’s innovation is to place them within the context of Homer’s emerging fascination with the intersection between sea and shore. What it offers, says guest curator Bill Cross, “is a journey of his formation as a marine painter across six waterfront destinations and across 11 years, from age 33 to age 44.” Further, “it is an experience of art in context…one in which we are regarding Homer as rooted in place and rooted within a cultural context, a social context, an economic context and a historical context, and there are artifacts which can help tell that story.”

Committed to that idea of context, Cross has organized the exhibition not to frontload Cape Ann’s outsized role in that story, but to begin it where it begins: in the upscale watering holes of postbellum America. For all that Homer tends to be remembered now as a sort of Old Man and the Sea of American landscape painting, in 1868 he was young and urbane, a Boston Brahmin recently returned from ten months in Paris, and the seascapes he first painted were ones in which the sight of well-dressed young women, skirts fluttering in the wind, were just as bracing as the water of the Atlantic.

-1024x733.jpg)

“Waiting for Dad (Longing)” by Winslow Homer, 1873. Transparent and opaque watercolor on wove paper.

Collection of Mills College Art Museum, gift of Jane C. Tolman. — On view at The Cape Ann Museum, “Winslow Homer at the Beach.”

Homer’s interest in fashion, well established in his early graphic output, would continue to be felt in his work through the 1870s. But his single season at Long Branch, N.J., was the only time that he painted scenes of affluent tourists cavorting in the waves. One attempt was so derided by the critics – for its idiosyncratic composition and impressionistic technique – that he took a knife to it and split it in two. The resulting two paintings, “Beach Scene” and “On the Beach,” are presented here side-by-side but at slightly staggered heights, so that the compositions fit together like pieces of a jigsaw puzzle. The two works had been seen together before, but never alongside the study that preceded them, “The Beach” from the Met. Here, the three paintings together offer visitors a rare opportunity to experience this all-but-forgotten bit of Homeriana.

The summer after Long Branch, Homer went to Manchester, near the base of Cape Ann, also a growing resort town but somewhat less trafficked than Long Branch. There Homer painted idyllic sandy shorelines, carefully selecting his view to crop out the summer homes that were springing up everywhere. Cross contrasts this strategy to that of Cape Ann’s native son, Fitz Henry Lane, who was known for his slavish attention to detail, and to Martin Johnson Heade, who was not above changing the orientation of the sun itself in order to enhance a view. “Homer goes a third way,” he notes. “To him the procedure is to select carefully and to paint not the thing, but the appearance of the thing.”

It was Lane’s hometown of Gloucester, near the tip of Cape Ann, that was truly the nursery for Homer’s coming-of-age as a painter of the sea. There was the scenery – the wide harbor, the islands, the marshes, the gulls – but there was also the noise and bustle and humanity of the fishing and shipbuilding industries. There, too, Homer began to experiment with watercolor in earnest, a medium that he had learned in part from his mother, a skilled amateur watercolorist. There are wonderful opportunities to see compositions like “Waiting for Dad/Dad’s Coming!” – a straw-hatted Gloucester youngster waiting for his father’s ship to come to shore – in both watercolor and wood engraving.

Homer was prolific in watercolor – Cross notes that his 1880 summer in Gloucester, just before his extended trip to England, was the most productive period of his life, wherein he produced some 100 watercolors in under three months. But Homer’s watercolors are guarded jealously by museums and rarely lent, because the delicate pigments will fade with prolonged exposure to light. Even so, the Cape Ann Museum has gathered together an impressive number of them, from the only two known works from his first watercolor exhibition (both from his 1873 sojourn in Gloucester), to several showstopper sunsets from the summer of 1880, to a handful of works that may come as a surprise to even the most seasoned Homer sightseer: delicate works from the artist’s brief stays in East Hampton, N.Y., and Greenwich, Conn. Looking closely, once again, at how women present themselves outdoors, both in the social arena and in moments of quiet reverie, these works are largely from private collections and are thus seldom seen or reproduced.

Watercolors are also an important part of the Harvard show. “Many of [Harvard’s] watercolors were part of the Winthrop collection, which [came] here in 1943 with the stipulation that it could never leave,” notes Ethan Lasser, Harvard’s curator of American art (Lasser has accepted the position of chair of the Art of the Americas at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, a position he starts in mid-September). “That’s kind of a blessing and a curse,” he adds, noting that while the watercolors are consequently in “mint condition” – loans, again, being particularly hard on watercolors – they have never been included in any of the major Homer exhibitions, and as a result are less well known.

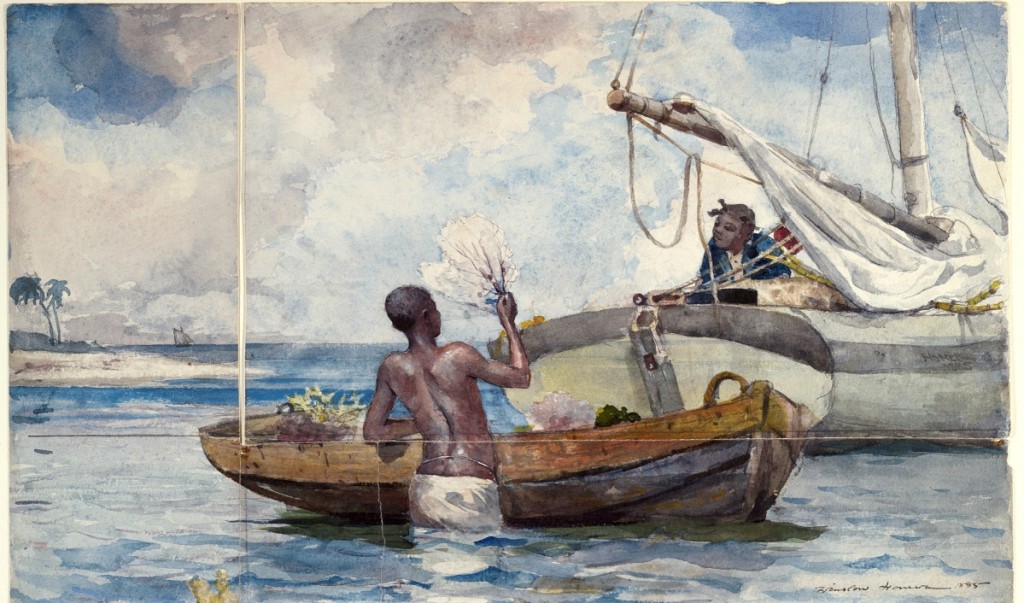

“Sea Garden, Bahamas,” by Winslow Homer, 1885, shown with two fragments originally part of the drawing, on loan from Yale University Art Gallery. Watercolor over graphite on heavy white wove paper. Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, bequest of Grenville L. Winthrop, and Yale University Art Gallery, gift of Allen Evarts Foster, B.A. 1906. Photo Harvard Art Museums; ©President and Fellows of Harvard College. — On view at The Harvard Art Museums, “Winslow Homer: Eyewitness.”

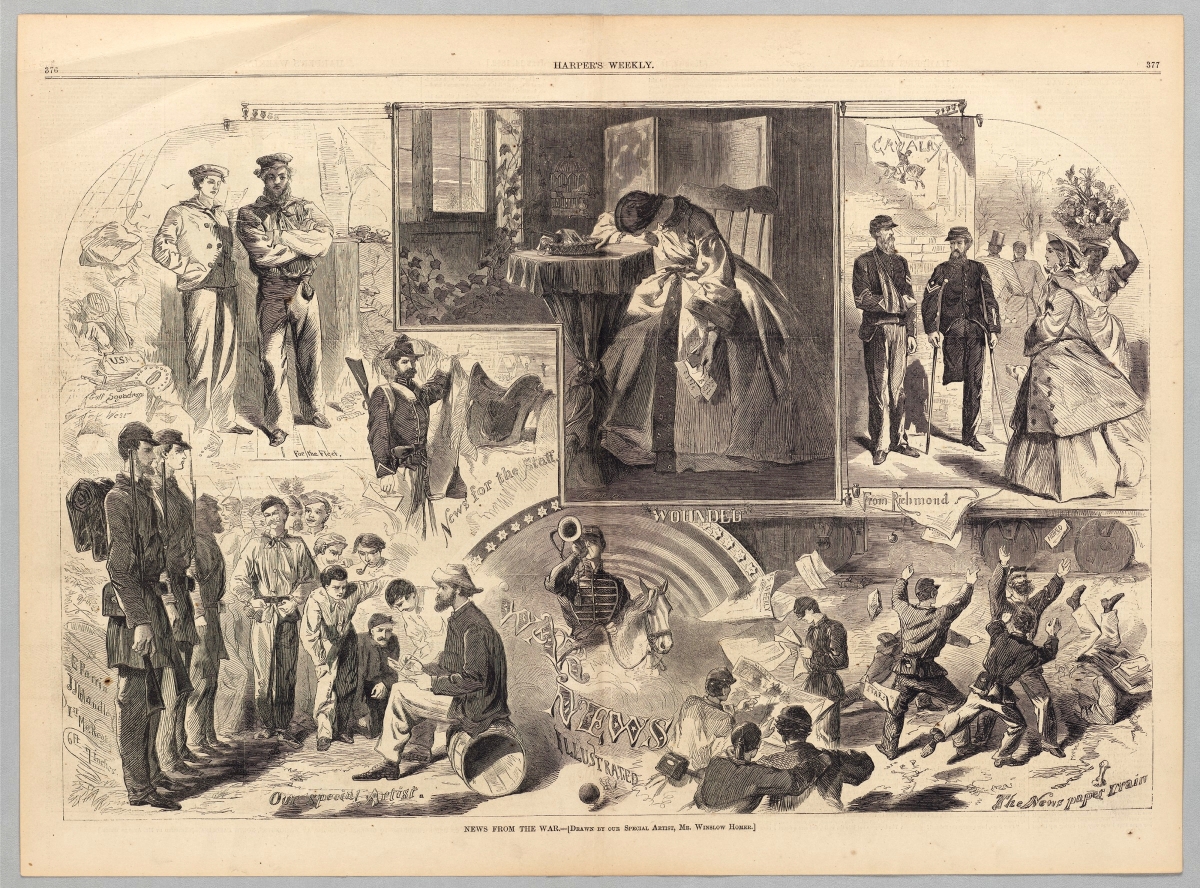

But while simply trotting out the “visual candybox” (Lasser’s words) of Harvard’s watercolors would certainly be enough of a crowdpleaser, Lasser says that with this exhibition they’re “trying to give them a more critical read…where we build on all the scholarship about Homer’s technique…but also think about big questions.” Here the watercolors provide a second half to a story that starts with Homer’s early work as a Civil War correspondent for Harper’s Weekly, producing drawings at the front (often Union army encampments) and then working with engravers to turn them into images that could be mass-produced in the popular magazine’s pages.

Illustrated newspapers and magazines were still a new medium at the time of the Civil War, Lasser observes. Consumers of news in the 1850s-60s were getting used to receiving information in a totally new way: through pictures as well as words. It was essential to publishers, then, that the images they commissioned and printed be as truthful as possible – or at least appear so. “We’re interested in the tricks that Homer and his fellow artists developed to convince the audience that what they’re showing is real, and based on their own observation,” says Lasser, “and the way that those habits of mind figure into Homer’s larger career as a realist.” Among those tricks: putting himself into the composition, either literally or symbolically (Lasser notes the paddler’s eye view in “Canoe in Rapids”); filling his scenes with a wealth of details that seemingly couldn’t be invented (“News from the War”); and suggesting the weather, the air or the time of day as a way to mark a certain place or event in time (“The Lookout”; “Sea Garden, Bahamas”).

The end of the war brought Homer the opportunity to dedicate himself more to painting, although his work for the illustrated press continued until well into the 1870s. Homer’s very first publicly exhibited oil painting, for example, was a Civil War theme – a sharpshooter perched on a tree limb, his rifle trained on a target – that he later reinterpreted as a wood engraving for Harper’s. The composition is a metaphor, in a way, for the theme that runs through both exhibitions: Homer as a keen observer, a selector, able to pinpoint his vision and his tools for maximum impact.

The Harvard show, like Cape Ann, can also boast a historic pairing of paintings: “Prisoners from the Front,” owned by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and Harvard’s own “The Brush Harrow,” both Civil War themes. According to Lasser, the paintings were both slated for the 1866 annual exhibition at New York’s National Academy of Design: “Homer arrives at the National Academy with two paintings, which are the same size and framed the same way, and the committee puts them in separate rooms…Some scholars have theorized or speculated that maybe they were meant to be pendants, so we’re going to be testing the idea by putting these two works together for the first time since they left Homer’s studio in April of 1866.”

“Sunset at Gloucester” by Winslow Homer, 1880. Watercolor and graphite on wove paper. Addison Gallery of American Art, Phillips Academy, Andover, Mass., gift of anonymous donor. Art Resource, N.Y. — On view at The Cape Ann Museum, “Winslow Homer at the Beach.”

Through this experiment, “Prisoners from the Front,” which Lasser says was a “greatest hit” from the moment it was first seen, will share some of the limelight with its lesser-known cohort. Moody and dark, “The Brush Harrow” is also enigmatic, showing two boys preparing an early morning – or is it twilit? – field for planting. “We’ll be offering an interpretation of it, but we’re very curious to have people think about that painting with us,” says Lasser. “Whether this is a kind of optimistic painting about the future, or a darker painting about who’s not there, and about the absence of all the people who didn’t come back from the battlefield, leaving a whole generation of young people without fathers and brothers and uncles.”

Homer’s career began in a context in which reportage took precedence over artistic expression, a job that required him to take on others’ experiences as his own and to make considered decisions about how to articulate those experiences for his audience. The theme that connects this summer’s two Homer shows, just 40 miles apart, is that his rootedness in eyewitness journalism, – the range of his experiences and the skills he acquired in order to convey them to his audience – continued to serve him even after he was free to choose his own subjects and approach. “He was very observant, and he was in many ways an American particular,” says Cross. “But out of the particular he mined meaning, which has given his work a universal power.”

The Cape Ann Museum is at 27 Pleasant Street in Gloucester, Mass. For information, www.capeannmuseum.org or 978-283-0455.

Harvard Art Museums are at 32 Quincy Street in Cambridge, Mass. For more information, www.harvardartmuseums.org or 617-495-9400.

.jpg)