-1024x764.jpg)

“French Trees” by James Scott (American, 1889-1967), n.d. Oil, 13 by 15 inches. Courtesy Ellen Stewart.

By Suzanne Hauspurg

KINGSTON, N.Y. – The Ulster County Historical Society and Museum has installed an exhibit, “The Art Colonies of Ulster County: Elverhoj, Cragsmoor and Byrdcliffe,” which is on view on weekends through October 30. Loans to this exhibit have been made by Cragsmoor Library, Cragsmoor Historical Society, Woodstock Byrdcliffe Guild, Woodstock Artists Association & Museum and several private collectors.

Interest in this subject began in 2018, when Dr William Rhoads, professor emeritus, SUNY New Paltz, along with local historian Vivian Wadlin, editor of AboutTown, a local history and business guide, heard of a sale of items being deaccessioned from the collection of the Newburgh Historical Society. They found a scrapbook, several design drawings and other ephemera pertaining to the extinct Elverhoj Art Colony of Milton, N.Y. Rhoads knew of the existence of the Elverhoj site during his early years of teaching; a student’s family purchased the property for use as a summer home. Rhoads and Wadlin decided to put together a group of researchers for the purpose of gathering more information on the little remembered art colony. Out of this has come a forthcoming book co-authored by Rhoads and Leslie Melvin, a vital member of the research group: Elverhoj: The Arts & Crafts Colony at Milton-on-Hudson, which has a publishing date in August 2022.

Prior to the mid-1800s, many American artists studying abroad learned to paint in the academic styles of the European masters. Art students of the 1850s returned to the United States to discover that their home surroundings offered as much, if not more, natural beauty than anything they had seen in Europe.

Ceramic blue and green glazed candle holder made by Sue Buttrick, Cragsmoor, 1930, 6 inches tall. Cragsmoor Historical Society.

Henry T. Tuckerman (1813-1871) a cultural essayist and critic promoted the development of a native school of American art primarily with landscape painting. In his first book, Sketches of American Painters (1847), he speaks of the area: “We can imagine no more desirable home in the country for a landscape painter. The variety of mountain stream, foliage and sky ever offered to his observation, furnish[es] exhaustless materials for study.”

Artists such as Thomas Cole (1801-1848) and Asher B. Durand (1796-1886) began to venture into the countryside and mountains of the Hudson Valley and upstate New York in search of fresh subject matter. Cole, considered the founder of the Hudson River School, was born in England but he wrote enthusiastically about his beloved Catskill Mountains with their “varied, undulating and exceedingly beautiful outlines.” Artists summered in scattered points along the Hudson and in the mountains. Some found rooms to rent, while others set up their own campsites. By the 1860s, many artists began building permanent homes and studios in the Hudson Valley and the Catskills. Although they may have lived near each other, the formation of “the artist’s colony” atmosphere did not begin until the 1880s.

The Industrial Revolution, which began first in England during the second half of the Eighteenth Century, brought massive factories and workhouses where products could be produced more quickly and cheaply for a rising middle class consumer. Early on, jobs created by these large machine-operated facilities were welcomed as the savior of the average working person. However, workers soon found themselves in a subservient position meant to benefit their employers at the expense of their own welfare. Sweatshops and child labor became rampant.

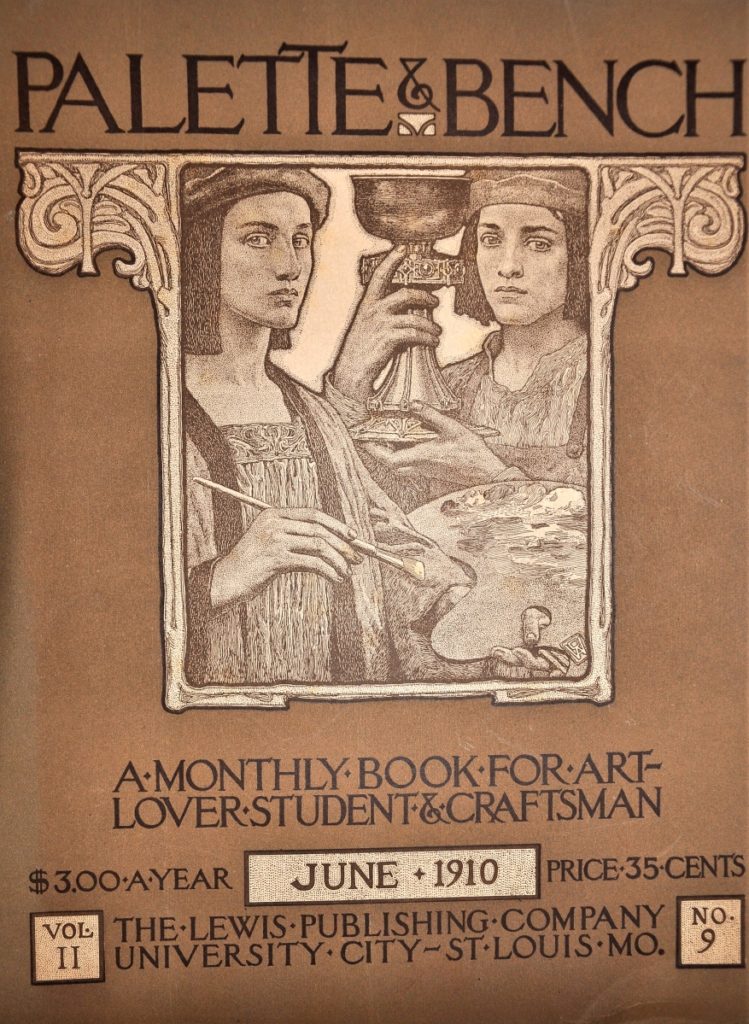

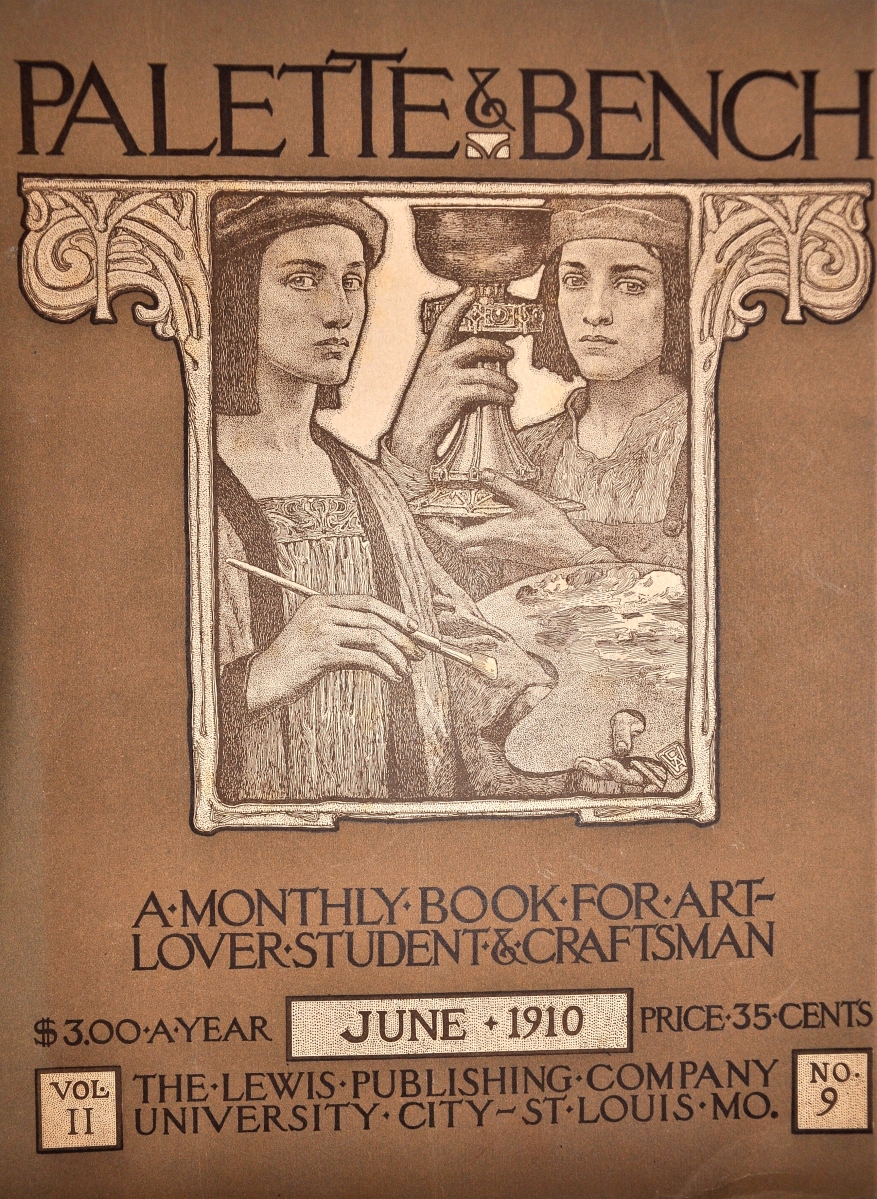

June 1910 issue of Palette & Bench Magazine, published in Cragsmoor by Charles Curran, et al. Cragsmoor Historical Society.

English critics such as John Ruskin (1819-1900) and the artist-designer William Morris (1834-1896) reacted sharply to the impoverishment of handcrafters and the working conditions in which they were forced to work. Artists, craftsmen and some wealthy art patrons believed that a healthy and moral society required independent workers who designed the things they made, and that handwork and craftsmanship merged dignity with labor. This would have an uplifting effect on all of society. Thus, the English Arts and Crafts Movement was born in the 1880s. The movement came to the United States a decade later as the same worker situations occurred in this country. In reaction to the decline in workplace conditions and worker compensation, craftsmen guilds and schools began to emerge on both sides of the Atlantic.

In the United States, the Arts and Crafts Movement influenced what would become known as the Craftsman Style and the development of “utopian” art communities: environments where one could live and work with others in a harmonious fashion, and where natural beauty was the driving force for inspiration and creativity. Previously, artists built homes of their own and worked alone. Now there was a desire to live and create within a larger, more diverse group. The beauty of the Hudson Valley and the Catskill Mountains in southeastern New York state was considered an inspirational setting for such artist “colonies.” Along with its natural beauty, the area was easily accessible to New York City and the global art market it fostered.

“The Art Colonies of Ulster County” discusses three art colonies located in Ulster County: Elverhoj (Milton), Cragsmoor (near Ellenville) and Byrdcliffe (Woodstock). Each began as a group of like-minded artists, choosing an inspirational setting and then building a community around a shared artistic philosophy that incorporated multiple types of art.

Two ceramic vases made by Jane and Ralph Whitehead, White Pines Pottery, Byrdcliffe. Woodstock Artists Association & Museum.

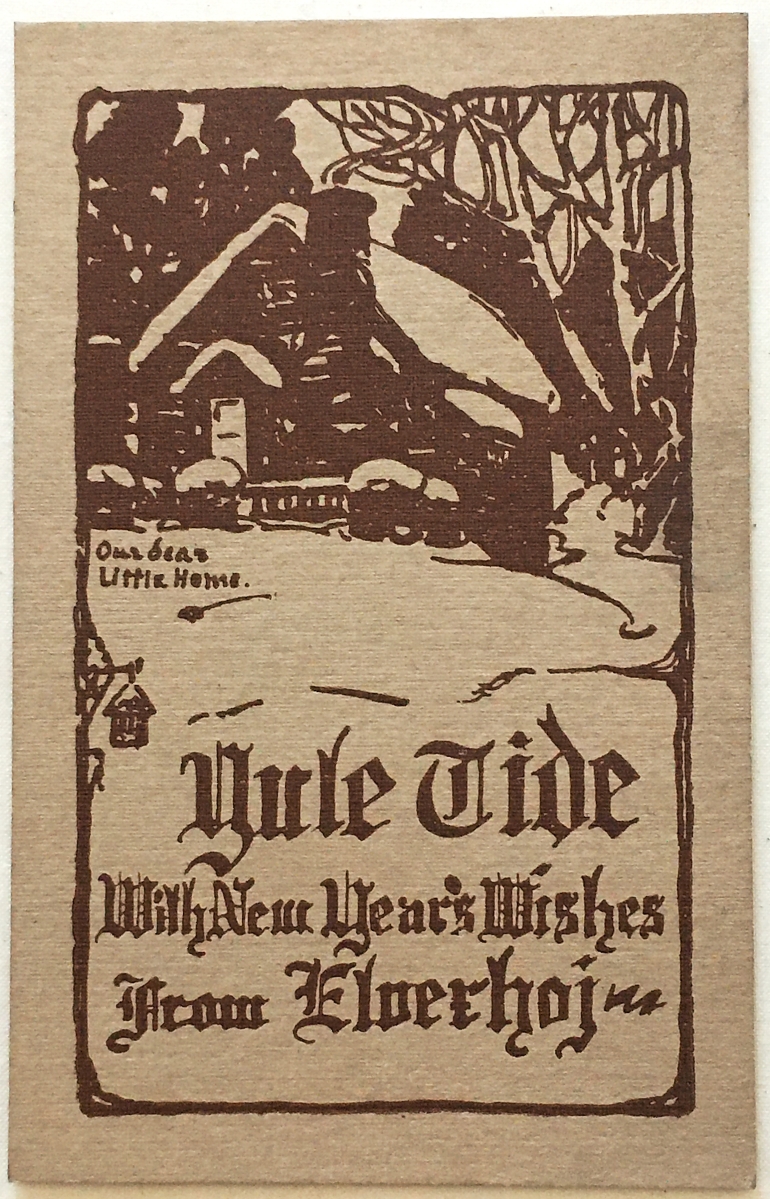

Elverhoj (Danish for “hill of the fairies,” pronounced “El-ver-hoy”) was an Arts and Crafts colony established in Milton on the picturesque west shore of the Hudson River in 1912 by Danish American artists and craftsmen, led by Anders Andersen. Little known today, the colony achieved a national reputation before World War I, earning a gold medal at the 1915 Panama-Pacific Exposition in San Francisco. That same year a favorable write-up in Gustav Stickley’s The Craftsman magazine with photos of the rustic studios added to the colony’s growing fame. Elverhoj was especially regarded for its jewelry and metalwork, but the works of painter-craftsman James Scott (1889-1967) and etcher Ralph Pearson (1883-1958) added to its renown, as did a fruitful connection with Vassar College, strengthened by the efforts of colony members Bessie (1893-1974) and Henrietta Scott (1897-1967), sisters talented in textile arts.

As part of the William Morris-inspired Arts and Crafts Movement, Elverhoj experienced a decline in the 1920s, partially offset by the opening of a theater with links to Broadway and the addition of a Moorish-style dining terrace. Still, the Depression dealt a fatal blow, despite Andersen’s enlisting the help of Eleanor Roosevelt. In 1935, the property was acquired by followers of the charismatic Black leader Father Divine, becoming one of his most popular “heavens.” Andersen, always the colony’s central figure, died in obscurity in 1944. Many of the items related to Elverhoj in this exhibition stem from an archive kept by Andersen.

Cragsmoor was the earliest artist’s colony in Ulster County, founded in 1882 by the painter Edward Lamson Henry (1841-1919). Born in Charleston, S.C., Henry was best known for his nostalgic, genre scenes of rural America. In 1882, he purchased property where he built his house and studio in the hamlet of Cragsmoor, on the Shawangunk Ridge outside of Ellenville. Henry’s friend and fellow painter Eliza Greatorex (1819-1897), along with explorer and amateur architect Frederick Dellenbaugh (1853-1935), came to visit him. The two were immediately enamored with the area, purchasing property and building house studios of their own in 1884. By 1903, the painter Austa Densmore Sturdevant (1855-1936) had built and was running the Cragsmoor Inn. This became the social hub of Cragsmoor, offering lodging, dining and musical entertainment.

Deer figurine, made in Elverhoj by James Scott, n.d. Sheet metal bronze, 4 by 4 inches. Ulster County Historical Society. Gift of Pat and Martha Wells in 2019.

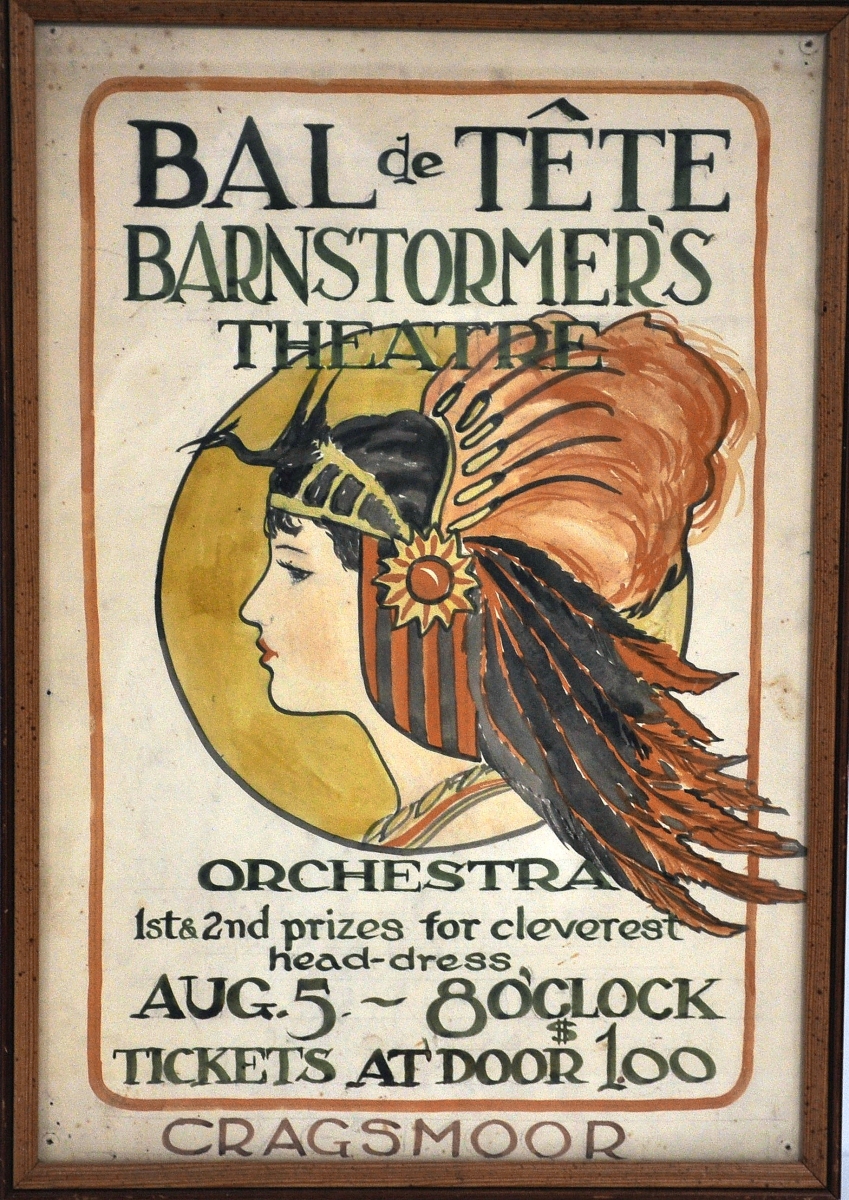

In 1906, Charles Curran (1861-1942) and Helen Turner (1858-1958), both students of the Art Students League in New York City, moved to Cragsmoor and set up shop. Curran was a painter and illustrator, while Turner was a painter, weaver and costume designer. In 1913, Dellenbaugh renovated a barn that he owned to create a summer-stock playhouse called the Barnstormers Theatre. In 1936, the Kinaloha Art School was founded by teachers, Rachel Taylor and Mary Sheppard, who moved to Cragsmoor to develop a summer vacation learning center for arts and handicrafts. In 1945, Marjorie and Vincent Roy became the co-directors of Kinaloha. To reach more audiences they created art classes for college credit through the State Teachers College in Oneonta, N.Y. Unfortunately, the school closed in 1950.

Today, the village of Cragsmoor remains an artist-friendly community. Many of the Dellenbaugh-designed house studios and municipal buildings are privately owned and well preserved.

Of the three art colonies in Ulster County represented in this exhibit, Byrdcliffe is the only one remaining active today.

Englishman Ralph Radcliffe Whitehead (1854-1929), founder of Byrdcliffe, was influenced by art critique John Ruskin (1819-1900) while attending Oxford University. Ruskin exposed him to the concept of an “ideal community,” where useful and well-made products could be created by artists to bring beauty to everyday life. Whitehead moved to America in 1892 and there met Jane Byrd McCall (1858-1955), who would become his wife. While working at Jane Addams’ Hull House, a center for social reform in Chicago, they befriended novelist Hervey White (1866-1944), who was looking to begin an artist’s community. Bolton Brown (1864-1936), founder of the art department at Stanford University near Menlo Park, Calif., and a painter, became acquainted with the two men. In 1902, they hired him to return to his native state of New York to search for a suitable site to establish an art colony. While climbing to the top of Overlook Mountain in northern Ulster County, Brown became enchanted with the natural scenery of the valley below him, which included the hamlet of Woodstock.

-1024x764.jpg)

Design drawing of a necklace, possibly by Anders H. Anderson, Elverhoj, n.d. Pencil. Courtesy Vivian Wadlin.

Whitehead approved of and purchased 1,200 acres of land for an art colony that he would call “Byrdcliffe” (combining parts of his name with those of his wife’s). The construction of buildings to be used as artist residences and studios began shortly thereafter. Workshops for furniture making, metalwork, pottery and weaving, along with a photography studio, were all included in the building scheme. The idea was that the colony would sustain itself through the sale of hand-made furniture while creating an environment that would inspire resident artists. Sadly, furniture production proved unsuccessful because Whitehead insisted upon a hand-made product that rejected the use of machinery, making the pieces too expensive. Instead, the colony turned to ceramics and other decorative arts as a means to support itself. Changes came quickly in the first years of the colony.

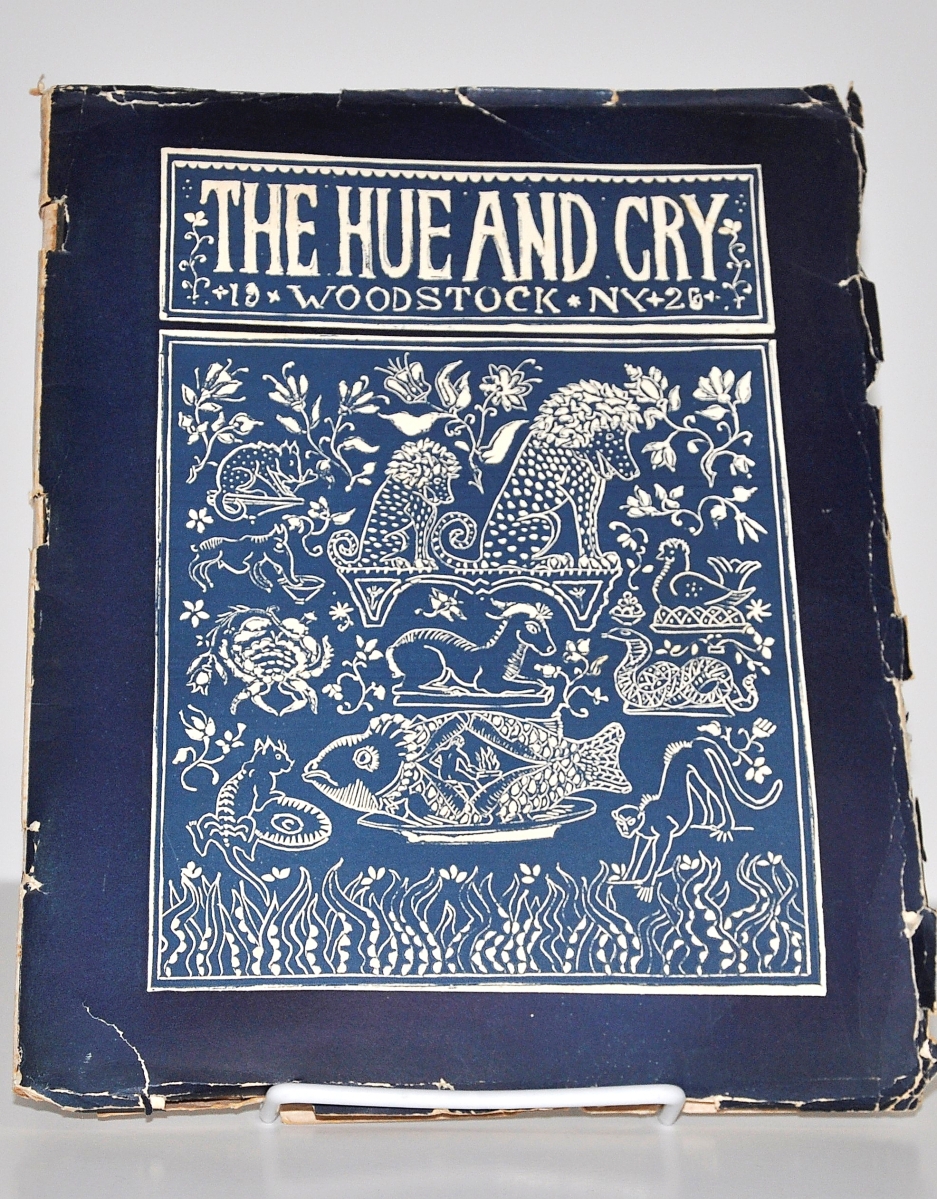

Whitehead demoted Bolton Brown from painting instructor to drawing instructor and in his place hired Herman Dudley Murphy (1867-1945), to teach painting for the summer session of 1903. Disappointed, Brown left the colony but remained in Woodstock working on his own for the remainder of his life. Hervey White left Byrdcliffe because he felt Whitehead’s vision was too restrictive and autocratic. In 1904, he purchased an area outside of Woodstock that he named the Maverick. Initially attracting writers and musicians, this area would later become the performing arts center of the Woodstock community, known as the Maverick Theatre.

L. Birge Harrison (1854-1929), a respected landscape painter from Philadelphia was hired. Harrison taught for only one summer but his influence on the colony was profound as in 1906, under his direction, the Art Students League (ASL) of New York set up a summer school at the colony. The ASL focus on landscape painting would become very important for many Woodstock artists.

When the 1913 International Exhibition of Modern Art (aka the Armory Show) came to New York, American artists heard the phrase “avant-garde” for the first time in association with the ideals of modernism. Twenty-four artists from the Byrdcliffe colony participated in this important exhibit. While the Art Students League supported the new modernism, clashes between artists at Byrdcliffe were bound to exist. To keep peace among the artists living in the community, the Woodstock Artists Association (WAA) was formed in 1919 with the mission “to give free and equal expression to both the ‘conservative’ and ‘radical’ elements because it believes a strong difference of opinion is a sign of health and an omen of long life for the colony.” Today, Woodstock village continues to be a mecca for artists. Woodstock Byrdcliffe Guild, Woodstock Artists Association & Museum and Maverick Concerts, Inc., still exist at their original sites.

“The Art Colonies of Ulster County: Elverhoj, Cragsmoor and Byrdcliffe,” on view on weekends through October 30 at the Ulster County Historical Society and Museum, is at 2682 US Route 209. For information, www.ulstercountyhs.org or 845-377-1040.

NOTE: Suzanne Hauspurg is the director of the Ulster County Historical Society.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)