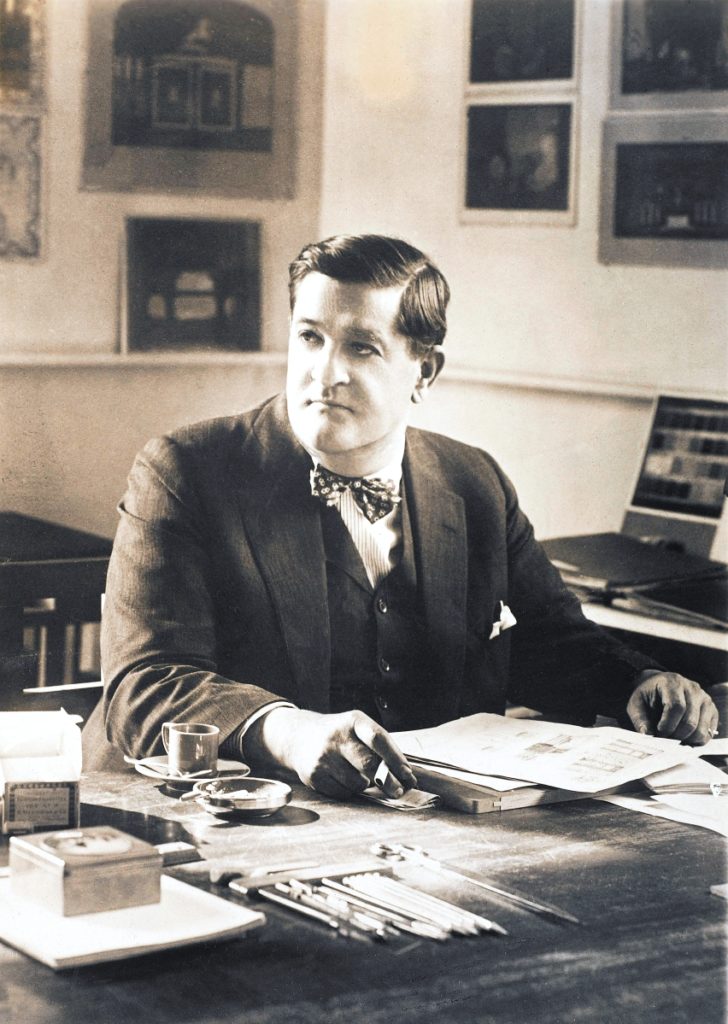

Joseph Urban in his office at William Randolph Hearst’s Cosmopolitan Pictures, New York, 1920. Joseph Urban Archive, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University.

By Laura Beach

CINCINNATI, OHIO – Period rooms have an uneasy place in the modern museum. Perceived relics of a bygone era of collecting, their fixed historical perspectives can seem, at best, insufficient; at worst, inauthentic. The Cincinnati Art Museum’s (CAM) decision to install, if temporarily, an interior long in storage, and to do so in an imaginative, contemporary way, is a bold stroke of which every curator will want to take note.

Designed by Joseph Urban (1872-1933), a foremost popularizer of Viennese Modern design in the United States, for Elaine Wormser (1912-2007), a Chicago teenager who lived with her parents in the fashionable Drake Tower, this Art Deco bedroom is literally the stuff of dreams. Wormser’s bed sits in a lofty meadow of dusky blues and greens, the tumult of the city below, adult life just ahead. Walls of black Vitrolite glass, furniture lacquered black to match and a ceiling of shimmering silver heighten the drama that Urban, whose diverse portfolio included set designs for stage and screen, so brilliantly sought to create.

On view through October 2, “Unlocking an Art Deco Bedroom by Joseph Urban” is the work of Amy Miller Dehan. Part of the team that developed the museum’s Cincinnati Wing and perhaps best known for her 2014 book and exhibition “Cincinnati Silver: 1788-1940,” the CAM curator of decorative arts and design marshalled a small army of conservators and other subject experts to recreate the Wormser bedroom in exacting detail. For Dehan, the key to the project was thinking of the room as Urban did, as a Gesamtkunstwerk, or total work of art. The delightful upshot is a narrowly focused display that, paradoxically, speaks to many audiences on a broad range of topics, from social and design history to the latest conservation techniques.

“Bedroom for Elaine Wormser,” detail, design by Joseph Urban, Chicago, 1930. Photography by Alvina Lenke Studios, 1930. Colorization based on recent research and added by Light Work, Syracuse, New York, 2020.

Dehan’s research undergirds every aspect of the project, which delves deeply into Urban’s overlooked influence on American Modernism, a topic New York’s Neue Galerie began addressing in “Wiener Werkstätte 1903-1932: The Luxury of Beauty,” a 2017-18 display whose catalog considered the Wiener Werkstätte’s short-lived New York showroom, which the Viennese-born Urban opened in 1922, 11 years after he emigrated to the United States.

“I started at the Joseph Urban Archive at Columbia University, a treasure trove in that so many of Urban’s other records were lost. I went through hundreds of boxes and found great things, like Urban’s watercolor drawing for the Wormser carpet. I don’t think anyone had realized what it was. It had been just a random watercolor design in a box of papers,” the curator says. At the Chicago Historical Society, she delved into the professional correspondence of Elaine’s father, Leo Wormser, a prominent Chicago attorney with advanced artistic tastes.

Why and how the Wormsers recruited Urban remains unclear. Elaine, who in 1936 married Thomas Reis and moved to Cincinnati, later suggested that her father met the New York-based designer through a client. Begun in 1929 and completed in roughly a year, the Wormser commission – whose proposed cost was about $117,500 in today’s money – is Urban’s only bedroom for a teenage girl on public view. Its prototype is “Repose,” which Urban designed for a 1928 exhibition at New York’s American Designers Gallery. Like many designers, he tended to recycle his best ideas. Dehan masterfully analyzes Urban’s oeuvre and relates elements of the Wormser commission – silvered ceiling; walls of opaque, black, reflective glass; black-lacquered furniture; wall hangings; carpet and lighting – to earlier Urban projects.

Mules, France, 1920-30. Silk, ostrich feathers. Cincinnati Art Museum, gift of Frederic Leonidas Woodbridge Jr. Dehan included costumes and accessories to tell a broader story about women and culture in the Jazz Age.

Mostly away at school, Elaine spent little time in her fantasy retreat, though she did enjoy entertaining friends there on occasion. Dehan speculates that the senior Wormsers, who otherwise lived with a smattering of English antiques, embraced avant-garde design for their daughter as part of their broader expectation that she would enjoy a modern, emancipated womanhood. As Leo wryly commented to a relative, “…E. is now independent and making her arrangements without consultation with her ancestors.”

The family’s reverie was brief. After Leo Wormser died unexpectedly in 1934, his widow and 22-year-old daughter left the Drake Tower. While they took what they could of the Art Deco bedroom and used elements in subsequent homes, built-ins such as the desk and dressing table were left behind and wall-to-wall carpet was placed in storage. In 1973, Elaine Wormser Reis gave what remained of the room to the CAM, where it forms the largest collection of Urban-designed furnishings in a public institution. Dehan continued research begun by her curatorial predecessor, Anita Ellis, hoping that the CAM would one day install the room, a project that began taking shape around 2014.

Conservators, fabricators and other technical experts are the behind-the-scenes stars of this show. Celebrated for his restoration of the Veteran’s Room at New York’s Park Avenue Armory, R. Mark Adams of New Hampshire calculated the exact scale and placement of objects in the Wormser bedroom, relying in part on a complicated technical analysis of black and white photographs taken of the room in 1930.

Bedroom for Nedenia Hutton, daughter of E.F. Hutton and Marjorie Merriweather Post Hutton, 1926, Mar-a-Lago, Palm Beach, Fla. Joseph Urban Archive, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University. Along with the Wormser commission, this interior is a rare Urban design for a girl’s bedroom.

Adams worked with cabinetmaker Terry Moore, also from New Hampshire, to develop scale models of missing furniture. In lieu of the Pyralin that Urban used to simulate ivory inlays and drawer pulls, Adams cast new inlays, just millimeters thick, of urethane plastic. “Problems occurred when the humidity wasn’t exactly right, so it’s been a challenge, but the results are absolutely stunning,” Dehan says.

Textile conservator Chandra Obie Linn painstakingly repaired splits in the silk taffeta bedcover. Missing fabrics were graphically recreated and digitally printed. Langhorne Carpet Company reproduced the carpet from a large, original fragment. The CAM consulted French-trained craftsman Bruno Paulin-Lopez on upholstery. For walls, the team substituted highly polished, black-acrylic panels for Urban’s Vitrolite. Objects conservator Kelly Rectenwald rewired lamps and cleaned and repaired ceramics.

In addition to the ceramics and glass collected by Elaine Wormser – the teenager loved perfume bottles and dog figurines – or selected as room accents by Urban, the exhibition incorporates paintings, works on paper, costumes and other furniture, some of it borrowed. Dehan says, “We are fortunate to have furnishings designed by Paul Frankl (1886-1958) that were owned by Marianne Hutton, a Cincinnatian who purchased them from his New York shop for her bedroom and dressing rooms. We use those pieces as well as costumes and accessories to explore the lives of women of the era.”

Analyzing the Wormser bedroom and working through its reinstallation crystalized the curator’s understanding of Urban and his artistic gift. She notes, “Perhaps the most obvious discoveries have been revelations about Urban’s striking combinations of color and finish, information that could not be conveyed in black and white photographs.” Catalog contributor Christopher Long observes, “Urban’s particular talent was to meld these disparate approaches into complete tableaux – scenes of complexity, light and opulence. He did so with a studied theatricality: even when he wasn’t designing stage sets, his interiors come off as places for drama-the drama of modern life.”

Mirror and seat by Paul Theodore Frankl (American, b Austria, 1886-1958), circa 1927. Wood, aluminum leaf, mirrored glass, paint and upholstery. Cincinnati Art Museum, gift of the estate of Mrs James M. Hutton II.

The Wormser bedroom may be stationary, but Dehan and her colleagues are not. They developed interactive digital content allowing audiences to explore the commission from multiple perspectives. The content will remain online after the room, regrettably, is dismantled to make space for other projects. As Dehan explains, “There was just so much that we wanted to unpack about the designer, the client, the craftsmen and their times. Visitors will be able to access label content for the room’s many components, from large built-in furniture to tiny dresser boxes. We look at objects and their histories, but also address themes relative to the time, such as the Art Deco style and its origins, changing roles for women during the 1920s, the growth of cities, migration and the Great Depression. We also share a good bit of research on the Mallin Furniture Company of New York, which created many of the Wormser furnishings.”

The book Joseph Urban: Unlocking an Art Deco Bedroom serves as a permanent record of the project. Published by the CAM in association with D Giles Limited, it pairs essays by Dehan, Long and Elizabeth McGoey with drawings and photographs, both archival and newly commissioned.

Despite Urban’s former prominence in the allied fields of architecture, interior decoration and set design, he is today barely remembered in the United States, something Dehan hopes will change. “I would love people to rediscover Urban and really understand his important contribution to American Modernism. He created beautiful, virtuosic interiors, buildings and other works of art, but he was equally important for bringing the Viennese Modern movement to the United States. I hope also that visitors leave this exhibition with a better sense of how dramatically the culture of the 1920s changed the lives of many women.”

The Cincinnati Art Museum is at 953 Eden Park Drive. For information, 513-721-2787 or www.cincinnatiartmuseum.org.