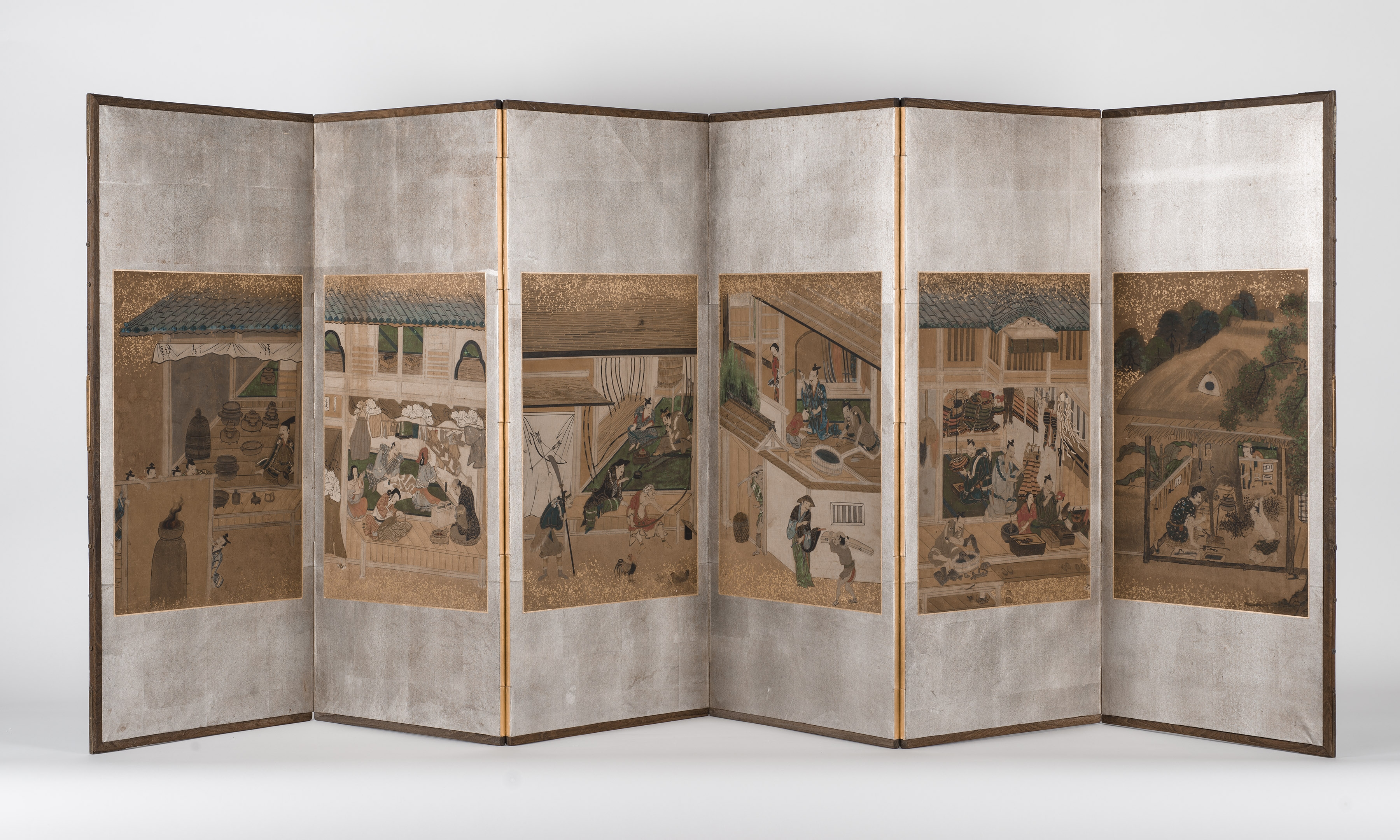

“Scenes of Craftsmen in their Workshops,” unidentified artist, early Seventeenth Century. Front side of a paneled screen painted on gold-ground paper, mounted on silvered panels.Unless otherwise noted, all objects are Japanese and from the collection of the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art.

By Kristin Nord

HARTFORD, CONN. — The year was 1853. Navy Commodore Matthew Perry, backed by two frigates and two sloops armed with 66 guns, sailed into Edo (Tokyo) Bay. Bearing gifts and a letter from US President Millard Fillmore, his mission was to convince Japanese ports to open to American trade.

William Heine, a lithographer on board one of the ships, captured the drama of this expedition in a series of works that became a sensation. Some 34,000 copies of his book sold in successive printings. Perry’s deliberations ended 200 years of Japanese isolation, opening the floodgates for the Western world that in the following decades would be mystified and dazzled by Japanese arts and culture.

A pivotal moment was the unveiling of the first British consul’s collection of decorative arts at the Great London Exposition of 1862. Subsequent exhibitions in New York, Dublin, Munich and Paris fanned exuberant flames. The 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia drew millions of visitors and ignited an American collecting craze. Hartford was an epicenter of wealth and influence at the time. Its well-heeled families were soon collecting all manner of Japanese exotica.

Through March 26, the Wadsworth Atheneum is revisiting this chapter of cultural history with “Utamaro and the Lure of Japan,” an exhibit that simultaneously showcases monumental works by this leading ukiyo-e artist while reacquainting the public with leading connoisseurs of Japanese art from Hartford’s Gilded Age. The impetus for the show came from the discovery of a missing Utamaro scroll painting in Hakone, Japan, believed to be a companion piece to two other large-scale paintings owned by the Wadsworth and by the Freer and Sackler, the Smithsonian’s museums of Asian art in Washington, D.C.

These works, which capture life in the pleasure districts of the Edo period (1650–1868), had reached the Paris art market by the late Nineteenth Century. “Cherry Blossoms at Yoshiwara,” circa 1793, passed through several hands in France before it was acquired by the Wadsworth in the late 1950s. “Moon at Shinagawa,” circa 1788, was acquired by the Detroit connoisseur Charles Lang Freer in 1903. The fate of “Snow at Fukagawa,” circa 1802-06, remained unknown for 70 years until it resurfaced at the Okada Museum of Art in Hakone in 2014.

Julie Nelson Davis, an expert in Japanese printmaking and author of Utamaro and the Splendor of Beauty, said in a recent interview that very little is known about the personal life of Utamaro, who lived from 1753 to 1806, but that he worked essentially as a “brush for hire,” promoting geishas and courtesans as celebrities in a highly competitive publishing industry. His mission was to generate business for the licensed entertainment districts… “while obscuring the fact that these women were prostitutes, typically serving out ten-year contracts of indenture.”

Julie Nelson Davis, an expert in Japanese printmaking and author of Utamaro and the Splendor of Beauty, said in a recent interview that very little is known about the personal life of Utamaro, who lived from 1753 to 1806, but that he worked essentially as a “brush for hire,” promoting geishas and courtesans as celebrities in a highly competitive publishing industry. His mission was to generate business for the licensed entertainment districts… “while obscuring the fact that these women were prostitutes, typically serving out ten-year contracts of indenture.”

Utamaro’s portraits are distinct, not only because of his skill as an artist, but because they imply that he had intimate knowledge of this hedonistic “floating world,” so much so that the late James Michener, a serious collector, claimed that in Utamaro’s finest works, “we sense the mind of the ‘eternal female.’” But Davis, a professor of art at the University of Pennsylvania and curator of a separate exhibition that will explore Utamaro’s work and legacy at the Freer/Sackler in April, suspects Utamaro’s persona could well have been a sophisticated marketing ploy. Who better to sell albums and guidebooks of geishas and courtesans than an artist cast as a bon vivant and sensualist, she asks, who purportedly had intimate knowledge of these women behind-the-scenes?

Ukiyo-e prints, which originally sold for the equivalent of “a haircut or a bowl or two of noodles,” Davis notes, had been successfully rebranded as fine art by the late Nineteenth Century, and dealers in Paris were doing a brisk business. It is perhaps no surprise that the frankly erotic material appealed to Parisians who were seeking a similarly exotic, stylish and sensual refuge from the present during the Belle Époque (1871–1914). At the same time, a vibrant American art publishing industry was catering to “an increasingly status-conscious, culturally insecure and affluent middle class, determined to join the consumer revolution begun by their counterparts in Europe,” William Hosley wrote in The Japan Idea: Art and Life in Victorian America.

“It was a combination of the right thing at the right time, and the ideas seemed to burst from nowhere,” he said recently. “Can you imagine — there aren’t many surprises in our connected world anymore, but in those days Japan was mysterious and unknown — and the response was kind of astonishing. Before the Civil War, furnishings may have been meager and clothes were left to descendants, but Victorians were becoming famous for their excess. Hartford was a boomtown, with residents paying one-seventh of the state’s taxes in the 1870s.”

Oliver Tostmann, the Susan More Hilles curator of European art at the Wadsworth Atheneum, delved into this rich time to curate this exhibition, selecting 103 objects from some 1,000 in the museum’s Asian collection to tell the tale. Three of Heine’s historic lithographs provide an introduction, while a monumental carved cabinet for objets d’art provides an opulent backdrop for two massive cloisonné urns acquired by Elizabeth Hart Colt for the family mansion, Armsmear, after seeing them at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition.

Tostmann drew heavily from the museum’s Elizabeth Hart Jarvis Colt and Mrs Jared K. Morse collections, as well as from bequests made by the Hilliard, Cutler, Avery and Mead families. These objects range from one-of-a-kind, mixed-metal knife handles and sword guards (tsubas), which would have been mounted like rare specimens under glass, to lacquerware, carved ivory and woven silk garments.

“This is the first time we’ve been able to exhibit our Japanese art comprehensively,” Tostmann said, “and it provides us with the rare opportunity to explore the rich history of collecting Japanese art in Connecticut and to reevaluate our holdings here at the Wadsworth Atheneum. Most of the objects selected for display have not been on view in decades.”

“The Atheneum is older than most museums, and I’d say that in its deep pockets of material you’ll find perhaps the most eclectic holdings in the country,” adds Hosley, a former curator at the institution.

An extensive collection of prints by additional ukiyo-e artists, including Toyokuni, Masanobu, Harunobu, Buncho and Shunsho, serve up portraits of the geishas and courtesans that functioned as celebrity instagrams in their day. A walk-through with Tostmann underscores the complexity of the symbols and the iconography imbedded in these cameos. Through facial gesture, body language, costume and background these works offer a detailed glimpse of the ideas, values and behaviors within a highly stratified society.

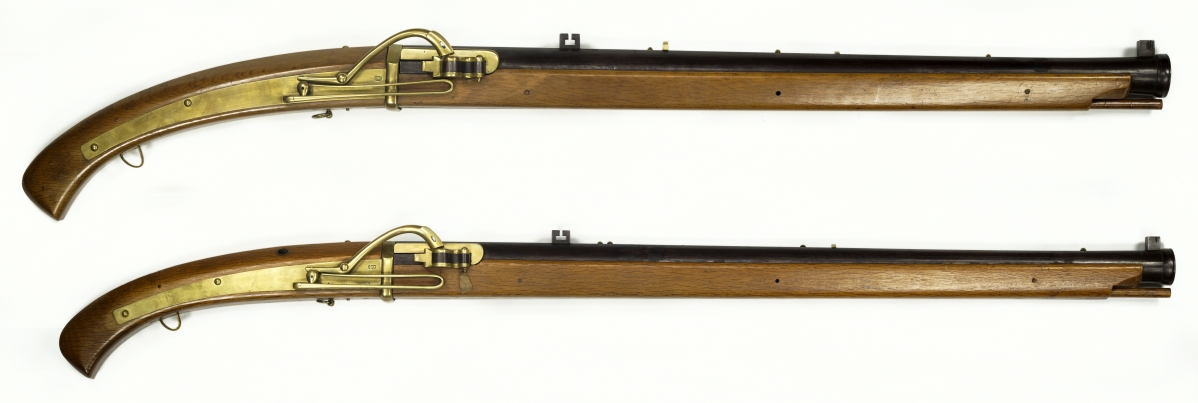

Also on view are matchlock guns given to Samuel Colt in the mid-1850s in return for the Colt revolvers he dispatched with Commodore Perry’s treaty delegation as gifts, and two swords, presented in exchange to Colt from the Japanese government.

“Cherry Blossoms at Yoshiwara” by Kitagawa Utamaro (1753–1806), circa 1793. Hanging scroll; ink, gouache, gold and gold leaf on bamboo paper.

For Tostmann, the six-paneled screen depicting workers from a dozen occupations in Seventeenth Century urban Japan brings Brueghel to mind. It was probably commissioned for a samurai residence and depicts a brushmaker, lacquer artist, yarn maker, dyer, pharmacist, Buddhist rosary bead maker, blacksmith, armorer, sword polisher, bowyer, chaps maker and metal caster.

The largest gallery space is dominated by three scroll paintings that scholars believe were created over a period of 18 years. Testifying to Utamaro’s skill as a painter of architecture and figures, they were owned by a wealthy merchant family named Zenno. The first record of them being displayed together was at Jogan Oji Temple, Tochigi Prefecture. “Cherry Blossoms at Yoshiwara” of circa 1793 is considered the most valuable work in the Atheneum’s holdings of Japanese art. It serves up a springtime cornucopia of courtesans and geishas, stationed on two levels in a tea house on the central boulevard of the pleasure district.

After the exhibit closes in Hartford, it will be on loan to the Freer for the follow-up exhibition “Inventing Utamaro: A Japanese Masterpiece Rediscovered” and to the Okada Museum in July in a final show focusing on the recurring symbols of snow, moon and flowers in Japanese art.

According to Davis, “These exhibitions offer a rare opportunity to see Utamaro from different perspectives. One is that of Edo-period audiences envisioning the floating world through Utamaro-style images, another is from the vantage point of fin-de-siècle collectors and dealers enthralled with his idealized views of feminine beauty. And the third is that of informed exploration of the many questions surrounding the paintings and Utamaro himself.”

About midway through the Atheneum’s galleries one encounters the 1857 landscape “Mountains and Streams in Winter” by Hiroshige, the last of the great ukiyo-e artists. Just 14½ inches by 29¼ inches, it is a brilliant display of color and abstraction. It and other prints by Hiroshige, says Tostmann, “influenced countless Westerners and helped them to see nature in a radically new light.”

The Wadsworth Atheneum is at 600 Main Street. For information, 860-278-2670 or www.thewadsworth.org.

Writer Kristin Nord’s work has appeared in publications throughout New England and Canada.